|

Guadalupe Mountains

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter X:

CULTURAL RESOURCE ISSUES

Cultural resources comprise remnants and evidence of human activity in the natural environment. Substantial federal concern with management of cultural resources on public land began with the Antiquities Act of 1906, was strengthened by the Historic Sites Act of 1935, and culminated in the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, which established the present National Register of Historic Places. Section 106 of the latter piece of legislation provided complicated review procedures to ensure that federal agencies gave proper consideration to cultural resources. In addition, Executive Order 11593, issued in 1971 and incorporated into the National Historic Preservation Act in 1980, required federal agencies to inventory cultural resources on the public lands they managed to determine which were eligible for listing in the National Register. Finally, the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 provided more specific guidelines for the protection of archeological resources on federally managed lands. These mandates all apply to Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Therefore, from fragmentary evidence of prehistoric use down to the Wallace Pratt residence that was built in the 1940s, park managers have been mandated to identify, evaluate, and, as appropriate, protect, and preserve the cultural resources found within the park boundaries.

While the array of responsibilities generated by the natural resources of the park has grown bewilderingly large since the establishment of the park, the demands of cultural resource management have remained relatively unchanged. During the first fifteen years of the park's operation, resource managers have identified and evaluated the historic structures and trails within the park and have determined the type of care each would receive. They have identified and evaluated prehistoric sites and have determined what means of preservation would be undertaken. They have also approved and supervised modifications made to adapt some historic structures for administrative use by park personnel and researchers.

When the park was established, many historic structures relating to nineteenth and twentieth century ranching operations existed within the boundaries of the park. In 1973, a survey of historic sites, conducted under contract by a team headed by William Griggs of Texas Tech University, established a baseline from which management decisions could be made. The report of the survey included photographs, scale drawings, and geographic locations for each of 47 sites. The team rated the structures for intrinsic and exemplary values and recommended treatment for them. [1]

Historians in the Regional Office used the information from the Texas Tech survey to classify the less obviously significant historic structures and sites in the park. When determining the historical significance of these sites, however, the regional staff apparently had some difficulty interpreting the assessments of the Texas Tech survey team. The survey report recommended preservation or restoration for interpretation for a number of the historic sites. In 1973 Park Superintendent Donald Dayton notified the Regional Director that he felt Regional personnel had "inadvertently made" a "false assumption" about the meaning of the term "historic" in the Texas Tech survey report. He was concerned because the historians in the Regional Office had recommended preservation for the entire complex of buildings at the Glover site. Dayton stated that he believed the survey team had used the term "historic" to distinguish modern structures from prehistoric structures, and had not used the term in the sense that it was used to determine eligibility for the National Register. While the Texas Tech survey recommended that seven of the sixteen structures in the Glover complex be preserved, Dayton pointed out that many of the structures the survey team recommended for preservation or restoration were simply "'best examples of' certain types of structures to be found within the park boundaries" and did not "have even 'Regional' significance as historic structures." [2]

Dayton apparently convinced Theodore Thompson, the Acting Regional Director, of the false assumption of Regional historians. Thompson responded to Dayton early in 1974 and provided a new list of classifications for all of the structures in the Texas Tech survey. Thirteen of the buildings on the Glover property that were under 50 years old had been determined to be of no historical or architectural value and had been delegated to the authority of the Park Superintendent for disposition. The Glover ranch house and cafe, both more than 50 years old, had been classified as having no historical or architectural value but required authority from the Associate Director of Professional Services in the Washington office for disposition. Seven structures or sites were classified as having obvious or possible historical value, regardless of age, and required interim preservation and protection until further research was completed to determine National Register eligibility. Finally, 18 structures, primarily small cabins, dugouts, and structures related to historic water systems in the high country, were determined to have no potential for listing in the National Register, but they were of enough interest to "warrant strong recommendation that they be left undisturbed except by justifiable action." [3]

Regional historians concluded that only one of the seven sites classified as needing more research was eligible for nomination to the National Register: the Wallace Pratt residence. The other sites were treated in varying ways. In 1975, the Houser house, dugout, and sheep-shearing pens near the Pine Springs campground were evaluated and determined to be insignificant historically, clearing the way for removal of the badly deteriorated structures in the following year. Historians determined that backcountry structures should be treated as discovery sites and allowed to molder naturally unless they posed a hazard to human safety. [4]

The Statement for Management that was approved in 1976 established four "historic zones" in the park. According to the statement, resources in these zones had been listed or had been determined to be eligible for listing in the National Register. The resources in these zones did not include any of those identified in the Texas Tech survey. The zones included: an area near Pine Springs that contained two sites, the ruins of the Pinery, which was a stage-stop on the Butterfield Overland Mail route, and an early cavalry encampment; an area surrounding the Williams ranch house; an area around the Frijole ranch house; and the area around the Pratt's stone cabin in McKittrick Canyon. Management planned that development in the historic zones would be minimal. [5] Since 1976 one additional historic resource has been identified and, while not part of a designated historic zone within the park, has claimed particular attention from resource managers: the Emigrant Trail. The trail coincides in many places with the route traveled by the wagons of the Butterfield Overland Mail.

While prehistoric resources also required the attention of management, they were less easily identified. Site surveys conducted in the early 1970s comprised the baseline for management of these resources, but trained personnel from the park, the Southwest Regional Office, and the Texas Historical Commission conducted additional surveys before each construction project was initiated in the park to ensure that important prehistoric cultural resources were not destroyed.

In this chapter four major issues relating to cultural resources will be considered: preservation of historic structures and the Emigrant Trail, adaptive use of historic structures, archeological issues, and finally, problems relating to the Glover property as a cultural resource.

Preservation of Historic Structures and the Emigrant Trail

The Pinery

The ruins of the Pinery, a fort-like stone structure built in 1858 to serve as a stage station for the Butterfield Overland Mail, demanded the immediate attention of cultural resource managers when the park was established. In 1972 David G. Battle, Historical Architect for the Southwest Region, visited the park to determine which historic resources might be eligible for nomination to the National Register. Although little remained of the Pinery's 30-inch thick and 11-foot high walls built of limestone slabs (see Figure 31), there was little doubt that the site was significant enough to be listed in the National Register. [6]

Between September 1858 and August 1859, the Pinery was a meal and mule stop for the "Celerity" wagons that carried mail and passengers between St. Louis and San Francisco. It was built like a fort, with interior rooms attached lean-to style to the thick exterior walls. The station comprised a wagon-repair shop and smithy, a kitchen, and a corral for livestock. After the first year of operation of the mail service, Butterfield managers determined that a route passing by Fort Stockton and Fort Davis offered more protection from Indians and better access to water, so the Pinery was abandoned. The station, however, continued to serve as a stopping off place for west-bound emigrants, soldiers, drovers, and freighters as late as 1885. [7]

In 1972, only the north wall of the original structure remained and Battle worried about the deterioration that was taking place. He estimated that a substantial portion of the west end of the wall had collapsed since the Park Service had acquired the property and noted that about half of the remaining wall listed at a 10-degree angle. [8] In 1973 the Park Service took emergency measures to stabilize the wall and Battle completed a Historic Structure Report for the Pinery. In 1974 Park Service specialists began realigning and re-mortaring the wall. Archeologists tested the site to validate drawings and dimensions of the buildings that Battle had reported in the Historic Structure Report. Stabilization of the wall was completed in 1975. The Pinery was nominated to the National Register in 1973 and was accepted for listing. [9]

The Pinery is the most accessible of all the historic resources at Guadalupe Mountains, being visible from Highway 62/180 and on the road to the Pine Springs Campground. The site had attracted attention, however, even before being acquired by the Park Service. During the early 1950s, J.C. Hunter, Jr., and the Glovers deeded the Pinery site and a small parcel of adjacent land to American Airlines. Officials at the airline desired to restore the stage station as a memorial to the carriers of the mail who had passed by Guadalupe Peak. During the 1930s American Airlines had received the first government contract for air mail service between St. Louis and San Francisco, just as the Butterfield Overland Mail Company had received the first government contract for overland mail service between the two cities. Plans for restoration advanced to the point of requesting bids, but high costs forced the company to abandon the idea of restoration and to return the land to the former owners. The officials at the airline were undaunted, however, and refused to give up the idea of a memorial. At the Pinery on September 29, 1958, officials and veteran pilots of American Airlines dedicated a granite monument that had been placed to call attention to another monument, a six-foot high stainless steel trylon placed on Guadalupe Peak (see Figure 32). Both monuments were inscribed to commemorate the centennial of the transcontinental overland mail and "the airmen who, like the stage drivers before them, challenged the elements through this pass with the pioneer spirit and courage which resulted in a vast system of airline transport known as American Airlines." The plaques on each of the three sides of the marker on Guadalupe Peak also called attention to the three-way partnership of Federal government, private enterprise, and rugged individuals that advanced westward expansion. [10]

|

| Figure 31. A view of remnants of the north wall of the Pinery stage station, a historic resource of Guadalupe Mountains National Park that has been listed in the National Register. The station was a stop on the route of the Butterfield Overland Mail and was used from September 1958 to August 1859. In 1975, Park Service specialists finished realigning and remortaring the remains of the wall to prevent further deterioration. (NPS Photo) |

The memorial on Guadalupe Peak has caught the attention of park visitors who wonder about the appropriateness of such a monument in a national park. In 1975 Superintendent Dayton responded to a visitor who wrote to him with such a complaint. Dayton suggested that although the Park Service probably would not have permitted installation of such a marker if the park had been in existence, he felt that the marker should not be removed or relocated. He admitted that if the history and purpose behind the marker were better explained to visitors, it might be more acceptable to hikers and climbers who visited the peak. The next month Acting Regional Director Monte E. Fitch corresponded with Dayton to affirm the stand Dayton had taken about the marker. [11]

The Emigrant Trail to California and the Butterfield Stage Route

Another historic resource of the park closely associated in time with the Pinery is the road traveled by California-bound emigrants and later the Butterfield stages. Although park managers were aware of the existence of remnants of the road within the park, it received little attention as a cultural resource until 1977 when Regional personnel determined that a National Register nomination should be prepared. Since the best-preserved portions of the road are on the west side of the park, it was that area that was selected for nomination. The nomination was submitted late in 1977 but was rejected because of "substantive and technical questions." The staff at the National Register wanted more than a representative sample of the trail. They preferred to see the nomination include all vestiges of the trail that met the qualification of historic integrity. [12] The revisions required for the nomination of the Emigrant Trail were not simple to make. Regional personnel took another look at the traces of the road in 1980 and then let the matter drop for several years. [13]

|

| Figure 32. The pilot memorial erected in 1958 by American Airlines at the summit of Guadalupe Peak. The six-foot high stainless steel trylon, erected before the authorization of Guadalupe Mountains National Park, commemorates the carriers of transcontinental overland and air mail. (NPS Photo) |

In 1985, Betsy Swanson, who had a track record of writing successful National Register nominations, received a contract to complete the nomination of the Emigrant Trail. After a year of work, Swanson still had many questions about the nomination, such as whether natural landmarks should be included in the nomination, how wide the corridor should be, whether portions of the trail that could not be verified because of time and funding constraints should be included in the nomination, how the concept of integrity should be applied to trails, and how much examination of trail remains outside the park should be accomplished to assist with research on the in-park remains. Diane Jung, Survey Historian for the Southwest Region, visited the park late in September 1986, hoping to iron out the problems. After on-site research and discussions with National Register staff members, Jung and Swanson determined that natural landmarks, such as springs and El Capitan, should be included in the nomination. They agreed to a 500-foot wide corridor on either side of the nominated traces of the trail. Trail traces that could not be verified on the ground would not be included in the nomination. Trail traces would be considered of sufficient integrity for nomination where evidence on the ground agreed with documentary evidence. Swanson and Jung decided that the nomination should take the form of a historic district with discontinuous boundaries. [14]

Six months later, James "Jake" Ivey, Historian and Historical Archeologist from the Regional Office, visited the park to examine Swanson's claim that there was integrity to the section of the historic district near the Pinery. However, due to the amount of disturbance caused by ranching use, he was unable to recognize any traces of the stage road or the Emigrant Trail and concluded that the majority of the stage road probably was under the present highway. As a result, he could not justify including any area around the Pinery ruins as part of the discontinuous historic district for the Emigrant Trail. Ivey agreed, however, that the trail was clearly visible in the west-side historic districts Swanson designated for nomination. [15] By the end of 1987 no further work had been done on the nomination.

The proposed addition to the west side of the park being considered in 1987 included more traces of the Emigrant Trail. If this area were added to the park, the additional traces of the trail would also have to be considered for nomination to the National Register. During the study of the proposed boundary expansion, the Texas Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer expressed concern that archeological data for the proposed acquisition was sketchy and needed to be enlarged before sound cultural resource management plans for the area could be developed. In another action related to the boundary expansion, Regional Office staff consulted with officials from neighboring Hudspeth County who were planning to construct a road from Dell City to the western park boundary. The route originally proposed by the county coincided with the route of the Butterfield Trail. After consultation, the county agreed to relocate the route of the new road so that the historic trail could be preserved [16].

Williams Ranch

The Williams ranch house, located on the west side of the park near the mouth of Bone Canyon, may be the least visited of the park's historic resources. During most of the year the eight-mile-long road from Highway 62/180 is suitable only for 4-wheel-drive vehicles; the remainder of the time a high-clearance pick-up truck is required. The road is blocked at the highway by a locked gate for which visitors may check out a key from the park's information center.

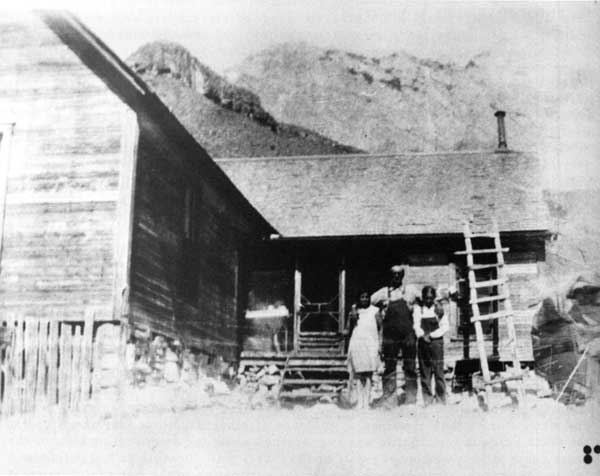

The frame house with steeply gabled roof (see Figures 33 and 34), reminiscent of houses more often found in the Midwest than in the rural areas of West Texas, was built soon after 1900 with lumber hauled by mule train from Van Horn, Texas. It served as headquarters for a longhorn cattle ranching operation for more than a decade. Ownership changed in 1915 and the new owner raised cattle, sheep, and goats and farmed a limited amount of land until his death in 1942. Historically, the house is significant as a remnant of the ranching operations that provided a livelihood for the settlers of West Texas. In addition, the house is an architectural anomaly in the area, an attribute which adds to its significance. [17]

David Battle visited Williams Ranch in 1972 to determine whether the house was eligible for nomination to the National Register. While the house was the only intact structure at the site when the Park Service acquired the property, ruins of a barn and water storage tank remained as evidence of other structures that once stood at the ranch headquarters. Battle was as concerned about the deteriorating state of the ranch house as he was about the state of the Pinery wall. Because he had determined informally that the structure was eligible for nomination to the National Register it required protection. The frame structure was still in sound condition, but the stone foundation appeared to be in danger of "imminent" collapse, a circumstance, he believed, that could destroy the entire resource. Battle recommended repair of the foundation and other deteriorated structural elements and placement of temporary closures over windows, doors, chimneys, and other openings that might admit animals or humans. [18]

|

| Figure 33. James Adolphus "Dolph" Williams and unidentified girls in front of the Williams ranch house, date unknown. The Williams ranch house on the west side of Guadalupe Mountains National Park is the most isolated of the park's historical resources. Constructed around the turn of the twentieth century, the house stands as a reminder of the ranching operations that provided a livelihood for residents of the area in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. Lumber for the structure had to be hauled by mule train from Van Horn, Texas. (NPS Photo) |

|

|

Figure 34. Another view of the Williams ranch house. Its architectural

design makes it an anomaly on the West Texas landscape. (NPS Photo) |

Park personnel followed Battle's recommendations. In 1973 they replaced the roof of the ranch house and stabilized its foundation. By 1977 the house had been treated with a wood preservative and the stone foundation rebuilt. Photographs of the water system were made to provide documentation for future reference. After those measures were complete, conservation specialists from the Regional Office considered the building to be stabilized and in a holding condition. They recommended bimonthly inspections of the exterior and annual inspections of the interior. In 1984 park personnel followed preservation recommendations, treating the exterior surfaces with wood preservative every fifth year after 1979. As of 1988, the Regional staff had not formally determined whether the ranch house was eligible for listing in the National Register, so a nomination had not been prepared nor had a formal management plan for the structure been written. [19]

Pratt Stone Cabin

The stone cabin that was formerly the summer home of the Wallace Pratt family stands on the flood plain at the junction of North and South McKittrick Canyons. As described in Chapter III, Pratt had the cabin built in 1930 to serve as a summer home for his family (see Figure 35). Two other structures complete the cabin complex: a building that contains a two-car garage and caretaker's quarters, and a pumphouse. Stone fences border the property on the south and west. [20] Soon after Battle's visit to the park in 1972, Regional staff prepared and submitted a National Register nomination for the cabin complex, which was subsequently accepted. The structures are significant for their unique architecture as well as for Wallace Pratt's stature in the nation as scientist, businessman, and conservationist. [21]

Although seasonal rangers were stationed at the Stone Cabin during the 1970s, and some researchers also used it during this period, the cabin has been little used for administrative purposes since that time. It has never been open to the public. For the comfort of personnel using the cabin, the Park Service installed electric heating. Later, contractors and park personnel restored the roofs of the house, garage, and pumphouse in stages from 1976 to 1984. They replaced roof supports, rafters, and decking and waterproofed the roofs. Vance Phenix, the architect who supervised the construction of the cabin, visited the site in 1981 and viewed the roof repairs with some interest. He had been skeptical about whether the roofs, constructed of natural stone shingles about one-half inch thick and mortared in place, would prove to be substantial. While the major roof restoration necessary by the late-1970s may have validated Phenix's initial skepticism about the permanence of the mortar bonds, it also may have been the result of less-than-regular maintenance after the Pratts moved to the Ship on the Desert. [22]

|

| Figure 35. Wallace Pratt's stone cabin in McKittrick Canyon. Pratt had the cabin built in 1930 to use as a summer home for his family. It was built from local stone quarried on a nearby ranch. The Pratts intended to use the cabin as a retirement home but changed their minds after being trapped one time in the canyon during a flash flood. The cabin and its outbuildings are listed in the National Register. (NPS Photo) |

The only other preservation problem at the Stone Cabin occurred early in 1985 when the park's Facility Manager discovered an infestation of wood-boring ants in the cabin. Regional personnel recommended applying "Tie-Die PT 230" and "Perma-Dust PT240" insecticides. The applications were effective in controlling the ants, but park personnel continued to monitor the situation. [23]

Adaptive Use of Historic Resources

Resources managers have overseen the modifications needed to adapt two of the historic resources of the park--the ranch complex at Frijole Spring and the Ship on the Desert--for use by Park Service personnel and researchers who are working at the park. While resource managers made certain that the historical integrity of building exteriors was maintained, modifications to the interiors have made the Frijole buildings and the former Pratt residence into functional administrative facilities.

Frijole Ranch Facilities

In 1876, near Frijole Spring, the Rader brothers built the front portion of the present ranch house using native stone as their construction material. The Raders were the earliest cattle ranchers in this area of the southern Guadalupes. In 1906 the Smith family took over the ranch, becoming successful truck farmers as well as cattle ranchers. The Smiths made numerous additions to the ranch house. In 1910 they added dormers and a gabled roof covered with shake shingles. Then, around 1925 they built three rooms onto the rear of the house and added some new outbuildings--a bunkhouse, double toilet, pumphouse, and a wall-- all built of rubble stone masonry (see Figures 36 and 37). During the same time period the Smiths also constructed a frame spring-house and schoolhouse. While the Smiths lived at Frijole their home served as a community center and also as the local post office. [24] At the time that the federal government acquired the property, the Frijole ranch was the headquarters for J.C. Hunter, Jr.'s, Guadalupe Mountains Ranch. The historical significance of the Frijole ranch complex lies in its representation of early ranching in the Guadalupes as well as its significance to the community that grew up near Guadalupe Pass. In 1972, when Dave Battle assessed the Frijole structures, he determined they were eligible for listing in the National Register. Regional historians prepared and submitted the nomination late in 1977, which was subsequently accepted for listing. [25]

|

| Figure 36. Walter and Bertha Glover at the Frijole Ranch House, c. 1909. The Glovers were neighbors of the Smiths, who owned the ranch at that time. The ranch served as the local post office and rural community center. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 37. Frijole Ranch House, 1980. Listed in the National Register for its significance as a remnant of the early ranching economy in the Guadalupes, the Park Service has adapted the historic structure for administrative use. (NPS Photo) |

Park managers immediately recognized the interpretive value of the Frijole ranch and spoke of it in those terms in the early planning documents. All plans focused, however, on interpretations of the complex as a whole, to be viewed from outside, rather than restoring the interior of the buildings for any kind of interpretation. These plans, which persisted to 1987, may have reflected the long-term shortage of administrative facilities at Guadalupe Mountains that made it almost imperative to adapt the Frijole buildings for administrative use. However, adaptive use also was in line with the principles of cultural resource management, which encourage use of secondary structures to ensure their preservation. Park Ranger Roger Reisch lived at the Frijole ranch house from 1969 until 1980; his good nature and dedication to the park permitted him to accept without complaint a less-than-modern building that had also begun to deteriorate. [26] During the latter-1970s park personnel made some repairs and changes, primarily cosmetic, to the Frijole buildings. The ranch house was painted, the chimney was repaired and stabilized, and a new shake roof and shutters were added. The barn and springhouse were treated with wood preservative, and the springhouse was replastered. [27]

Between 1983 and 1985, personnel from the Regional Office and the park, assisted by contractors, completed major rehabilitation and renovation of the ranch house, barn, and other outbuildings, added a new septic system, and connected the water system for the Frijole complex to the Pine Springs well. In the ranch house, workers installed new support timbers beneath the floors, insulated the interior walls, reconstructed the dormers, installed storm sashes, replaced the electrical wiring, rebuilt and remortared portions of the chimney, and stabilized and remortared the foundation and the southeast exterior wall. The barn renovation included removing and replacing rotten siding, repairing doors, installing a plywood floor in the hay storage area, rodent-proofing the tack room, improving outside drainage, and installing new wiring. The double outhouse received a new and stronger roof structure and new roofing material; the wooden floor was strengthened and covered with tile flooring; interior finishes were restored or replaced with tile; and doors, toilet, shower, and lavatory fixtures were replaced. Workers replaced the roof and roof structure on the bunkhouse, replaced doors, reglazed windows, and repaired sashes. The springhouse also received roof work. A temporary drainage system installed around the schoolhouse allowed the wooden siding to dry out after years of contact with the earth. All utilities were placed underground and old lines were removed, but the posts and poles were left in place. In October 1983 the Frijole Ranger Division took over the ranch house as its headquarters and work space. [28]

Ship on the Desert

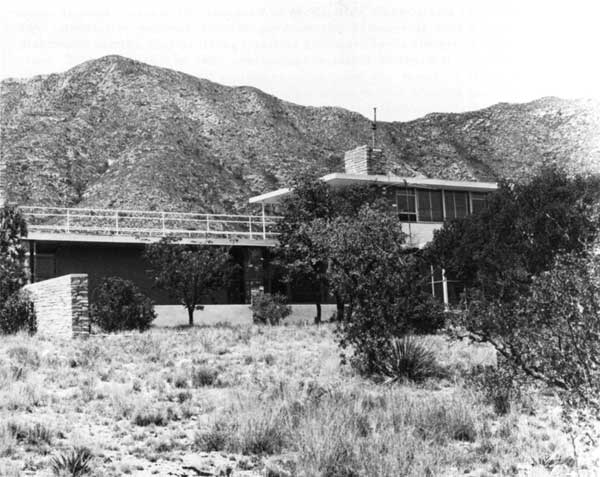

Regional historians believed that the importance of Wallace Pratt, combined with the style of architecture of the Ship on the Desert, qualified the structure for listing in the National Register. Architects conceived the building in International style and designed the former residence of Wallace and Iris Pratt to resemble an oil tanker. Begun in 1941 and completed in 1945, after wartime interruptions, the six-room house is basically a single story with a deck room on the second story (see Figure 38). The main floor contains six massive transverse walls built of native stone with structural steel providing the framework for the building (see Figure 39). A two-car garage and guest quarters form an ell on the northwest end of the house. The Ship was nominated to the National Register in 1978. The Keeper of the National Register returned the nomination in 1979, reminding the Regional staff of the Park Service that a structure must be 50 years old to be listed in the National Register. The Pratt residence would not be eligible until 1995. In 1985 Peter Maxon of the Texas Historical Commission spoke with Bill Bushong at the National Register office, inquiring whether there might be some flexibility about the Ship nomination. Maxon received a negative response. Subsequently, White Associates, a Lubbock architectural firm, prepared a new nomination, to be retained by the Regional Office until the appropriate time for submission. At the same time, White Associates developed a cyclical maintenance plan for the Pratt residence, designed to keep the structure historically accurate and structurally sound pending listing in the National Register. [29]

|

| Figure 38. The Wallace Pratt residence, the Ship on the Desert. Constructed during the early 1940s, architects designed the house to look like an oil tanker, symbolic of Pratt's career as a petroleum geologist. The structure will not be of sufficient age to list in the National Register until 1995. Although it serves as housing for park and research personnel, care has been taken to preserve the architectural integrity of the residence so that it may be listed in the Register. (NPS Photo) |

|

| Figure 39. The Ship on the Desert during construction. The structural steel framework of the building and massive walls of natural rock are apparent. (NPS Photo) |

The Ship has seen nearly as much administrative use as the Frijole ranch house. It served as a residence for Peter Sanchez from 1962 to 1963, for Roger Reisch from 1964 to 1969, then was the residence for Area Managers John Chapman, Bruce Fladmark, and Ralph Harris. After Harris moved out, renovations began. Since the house is some distance off the road to McKittrick Canyon and is unlikely to serve any interpretive purpose for the park in the foreseeable future, park managers planned to use the Ship as living quarters and work space for groups that were doing research at the park. In 1983 contractors installed 89 thermal windows. The next year a new pump and well equipment improved the water system. In 1985 the kitchen was remodeled: workers repainted cabinets and covered red tile walls and exposed wooden shelves with plastic laminate. In 1986 contractors reroofed the entire structure and supplied information about periodic maintenance necessary to validate the ten-year guarantee. While park managers originally intended to replace the flagstone deck that once covered the roof as a part of the re-roofing project, costs prohibited the restoration. [30]

Barry Sulam, Regional Historical Architect, noted at the end of the roofing project that preparation of a Historic Structure Report would enhance the chances of listing the Ship in the National Register. He also outlined a number of tasks that remained to be completed to preserve the "more significant original features" of the Ship. They included: replacement of the flagstone pavers on the roof deck, replacement of green glass and plexiglass panels with thermal glass, repair and replacement of exterior doors and hardware, waterproofing of interior masonry walls, rehabilitation of wooden slat blinds, restoration of interior color schemes and wall coverings, and replacement or repair of lighting fixtures and door and window hardware. [31]

Managing the Historic Resources

The greatest handicap for resource managers as they made decisions relating to the park's historic resources was that a Historic Structure Report had been prepared for only one structure: the Pinery. Similarly, there were no Historic Structure Preservation Guides for the classified structures. Without these two documents, resource managers do not have the baseline information from which management decisions can be made. Management recognized the need for these documents and made them high-priority items in resource management plans in both 1984 and 1987, but as of 1987 lack of funding had prevented their accomplishment.

Archeological Issues

Humans have utilized the lands that make up Guadalupe Mountains National Park for at least 10,000 years. In prehistoric times, nomadic people hunted game and gathered plant foods available at both low and higher elevations. Until modern ranchers utilized water from drilled wells and the larger springs of the area to irrigate crops, the southern Guadalupes had no permanent settlements or sedentary farmers. However, the archeological evidence of human use of the Guadalupes is rich. [32]

Caves or rockshelters, middens, and open campsites were the most common types of sites found in the southern Guadalupes and many are found in association with roads and trails. Park programs to aid in the protection of wide-spread archeological resources included non-disclosure of site locations, public education about the value and vulnerability of the resources, controlled access to caves, and ranger patrols. Fortunately, most of the archeological sites in the park were not discernible to the untrained observer and, therefore, were not apt to be wantonly damaged or pilfered. [33]

Archeologists began investigating the southern Guadalupes in the 1930s, but park-related surveys did not begin until 1970. In that year Harry J. Shafer of the University of Texas headed a preliminary survey conducted by the Texas Archeological Society. The volunteers visited 150 sites, 139 of which were previously unrecorded. The next year the Society conducted a field school in the vicinity of Pine Spring. Students excavated a terrace southwest of the barn and corral associated with the Houser house. In addition to this excavation, the field school also confirmed an area on the north side of the drainageway from Pine Spring as the site of an army bivouac area. In May 1973 Rex Gerald of the El Paso Centennial Museum made a professional field survey of the Pine Springs campground area and the route of the proposed tramway. The following summer Paul and Susanna Katz of Texas Tech conducted a six-week field school excavation in the Pine Spring campground area, continuing earlier efforts to analyze a site that would be negatively affected by visitor use and park development. [34]

In 1976 the Katzes completed the necessary field work to produce a complete inventory and assessment of archeological sites in the high country of the park, work they performed under a contract with the Park Service. They assessed a total of 85 sites, including previously recorded sites as well as ones identified during their survey. The report, published in 1978, listed 16 sites that the Katzes believed to be eligible for nomination to the National Register. The Katzes also developed specific criteria by which archeological sites could be evaluated to determine eligibility for listing, criteria that the legislative mandates did not make clear. The sites they believed to be eligible for listing were primarily ones that contained multiple middens, but also included three lithic scatters, two single middens, and one cave with a midden. As of 1987, researchers had recorded a total of 299 archeological sites in the park. Although they had recommended that 29 of the sites appeared to be eligible for listing in the National Register, by 1988 Regional historians had made no formal determinations of eligibility of any of the sites. [35]

Since the survey by the Katzes, most archeological resource management has taken the form of clearance surveys prior to prescribed burns or construction. In 1978 the Regional Office sent an archeologist to examine prescribed burn plots as park managers worked to develop a plan for fire management. The next year, prior to construction of the new access road into Dog Canyon, Regional Archeologists Bruce Anderson and Jim Bradford surveyed the area and found one midden mound in the path of the proposed road. They excavated and salvaged the mound and in 1980 published their findings in a report titled "Upper Dog Canyon Archeology." In that document Bradford outlined the precautions that were necessary during construction to protect other cultural resources near the roadway. He also expressed his concern that one of the archeological features of Dog Canyon had recently been damaged, either as a result of road construction or maintenance. He asked park managers to include archeological consultation in development projects as early as possible. Bradford returned to Dog Canyon in 1985 to assess the impact of a proposed expansion of the parking lot. His survey revealed that a midden mound would be directly affected, necessitating changes in the plans for expansion. During that visit Bradford also began to train the park's Resources Management Specialist to conduct small-scale archeological assessments in emergency situations that might occur in the day-to-day operation of the park. [36]

From 1979 to 1982, as development of the trail system took place, archeologists visited the park several times to give clearances before construction began. In some cases planners had to realign trails to avoid unrecognized archeological sites or to avoid creating erosion patterns that would affect archeological sites. [37]

The impact of natural forces such as the freeze-thaw cycle, wind, wildfire, soil erosion, burrowing animals, and grazing ungulates may be as harmful to archeological resources as the impacts of humans. Among the archeological resources, park managers have recognized the particular fragility of rock art. Although sites containing rock art comprise only four percent of the identified sites in the park, they typify the problems associated with managing archeological resources. Mere protection from intentional or unintentional human damage does not mean the resource will be preserved. Rock art, and all archeological resources, become part of the fabric of the land and are affected by the same natural phenomena that affect natural resources. As of 1987, the lack of in-depth research relating to the park's archeological resources had prevented park managers from developing long-term management plans for these cultural resources. [38]

The Glover Site

Chapter V describes the problems associated with the acquisition of the Glover property for inclusion in the park. In 1972, after condemnation proceedings, the Glovers accepted a cash settlement of $55,000 and received the right to live on their property and operate their business until the death of the last surviving spouse. Walter Glover died in 1973 at the age of 94; Bertha Glover died in August 1982 at the age of 89. [39] During the decade in which Bertha Glover continued to operate the Pine Springs Cafe, she and the park personnel at Guadalupe Mountains maintained a friendly, if distant, relationship.

A month after Bertha Glover's death, Area Manager Ralph Harris met with Mary Glover Hinson, the Glover's only daughter, who had been living with her mother. They discussed how much time Hinson needed to close the business and vacate the buildings. Hinson asked to wait at least until the end of the tax year. On September 14, 1982, after personnel in the Regional Land Resources Office determined that December 31, 1982, would be a "fair and reasonable" date for vacating the property, Superintendent William Dunmire sent a letter to Hinson notifying her of the year-end deadline. A few days later, William Bramhall, Chief, Division of Land Resources, wrote to Hinson and informed her of her eligibility for reimbursement for costs of moving. In mid-October, anticipating the imminent possession of the buildings on the Glover tract, Regional Director Robert Kerr wrote to the Associate Director of Cultural Resources Management in the Washington office of the Park Service, requesting authority to dispose of the structures in the Glover complex that were more than 50 years old. [40]

The response of the Associate Director to Kerr's request was undoubtedly postponed by the unexpected turn of events that occurred two weeks later. On October 26 a national newspaper carried the story of Mary Hinson and announced that Texas Senator Lloyd Bentsen had sent a written request to Superintendent Dunmire asking for an extension of time for Hinson to vacate the cafe. Earlier in October, the El Paso Times had carried a story about Hinson's pending dislocation, but it apparently drew little attention. The story in US News, however, definitely attracted attention. Early in November the story received television coverage on NBC and ABC. The coverage was not favorable to the Park Service. [41]

On November 2, Dunmire responded to the letter he had received from Bentsen. He acknowledged that the Park Service would be amenable to allowing Hinson more time to vacate, but that she would be required to pay rent on the buildings during the extended time period. He also addressed the planned removal of the buildings on the Glover tract. Saying that he still believed that it was in the highest public interest to remove the buildings to enhance the scenic integrity of the highway corridor, Dunmire told Bentsen that he had asked Park Service architects for another evaluation of the Pine Springs structures. [42]

At the same time, staff members from the offices of Secretary of the Interior James Watt and Congressman Richard White also became involved in the question of extending Hinson's occupancy of the Pine Springs buildings. Associate Director for Operations, Stanley T. Albright, from the Washington office of the Park Service responded briefly and factually to the query from the Interior Department, advising the staff member of the means of acquisition of the Glover property, the reservation attached to it, and the termination of the reservation with the death of Bertha Glover. He described the buildings on the property and emphasized the fact that the newspaper had distorted the situation by referring to Hinson's dislocation as an eviction. [43]

Dunmire responded to Congressman White's inquiry, which had been prompted by a communication from Duane Juvrud, Mary Hinson's attorney. White apparently was concerned with the water rights that were attached to the land the Glovers sold to the United States. Dunmire assured White that the water rights and the severance of those rights from the Glover's remaining 3,700 acres were included in the property for which the Glovers received compensation. He also indicated that Hinson should not assume that there would be excess water available from the sources on the former Glover property to divert to her ranch land adjacent to the park. Addressing another of White's queries, regarding the feasibility of Hinson continuing to operate a facility such as her parents had operated, Dunmire told White that a market study conducted in 1981 indicated a concession would not be economically feasible. He also pointed out the high cost of rehabilitating the Pine Springs store building to meet standards of safety and structural soundness. [44]

On November 30 Dunmire confirmed in writing the conversation he had with Mary Hinson the previous day. He had agreed to her request for a six-month extension of occupancy, setting June 30, 1983, as the date by which she would vacate the property. Dunmire also confirmed granting Hinson access to the Park Service water source at Pine Springs for residential, non-commercial use on her property adjacent to the park boundary. Hinson would be responsible for the cost of the line and hookup. A charge for water would be made, based either on cost or comparable rates in the City of Carlsbad, New Mexico, when Hinson had relocated her residence to this property. The following day Dunmire notified Senator Bentsen of the agreement. [45]

In spite of the apparent finality of the agreement between Dunmire and Hinson, due to the public and Congressional support Mary Hinson was able to gain, she still occupied the Pine Springs Cafe beyond the June 1983 extension. In the spring of 1983, hoping to "cool the issue" and believing that the decision was not harmful to the park, Superintendent Dunmire acquiesced to Hinson's request to continue to occupy the Pine Springs buildings for another year. He renewed her right to occupancy again in June 1984 and June 1985. [46] During these years Hinson paid $50 per month for rent and charges for water used in the store. In 1984, when construction of the park boundary fence cut off the water supply for livestock on land which Hinson had leased to J.C. Estes, park managers worked out an agreement with her to continue to provide water for a specified time until Estes could get a fair price for his cattle. That same year Dunmire also confirmed Hinson's right to use a Park Service access road to reach her property. Park Service personnel graded a short spur road from the paved road to the boundary line between the park and Hinson's property and installed a gate in the boundary fence to facilitate access to her property. [47]

Late in 1983 a staff member of the Regional History Division reassessed the historical significance of the buildings in the Glover complex. In a report entitled "Evaluation and Alternative Management Strategies: Pine Springs Camp (Glover Property) Guadalupe Mountains National Park, Texas," Laura Souilliere documented the Glover property from its establishment in the early twentieth century to its contemporary status. The Texas Historical Commission reviewed the report and determined the Glover property to be eligible for listing in the National Register under Criteria A, C, and D: it represented "an historic type frequently seen in desert regions of the Western United States," had made a "substantial contribution to the development of isolated desert population," and the oral history Mary Hinson could provide, "together with documentation from the property, [could] yield information important to the understanding of lifeways of early 20th Century families in this region of Texas. . . ." [48]

In January 1984, Melody Webb, Regional Chief of the Division of History, notified Dunmire of the decision of the State Historic Preservation Officer regarding the Pine Springs buildings. In anticipation of Hinson's vacating the cafe in June 1984, Webb advised Dunmire to add $7,000 to funds programmed for the demolition of the Pine Springs buildings to ensure that adverse effects would be mitigated through additional oral history, photography, and a full inventory of the contents of the buildings. [49] Webb's plans to document the buildings did not materialize, however, because of Hinson's continued occupancy.

Richard Smith succeeded Dunmire as Superintendent of Guadalupe Mountains on March 30, 1986. Smith attacked the thorny problem of the Glover property with the vigor of a new man on the job. Within a month he had reviewed the "voluminous" files relating to the property and had summarized their contents and implications for the Regional Director. He recommended that Hinson's use and occupancy permit not be renewed for another year and suggested that the Texas Congressional delegation and Hinson be notified immediately of that intention. He closed his memorandum by saying:

I am well aware that we risk considerable public controversy if we decide to pursue this course of action. . . . I am convinced, however, that we should not continue to issue the 1-year use and occupancy agreements to Mrs. Hinson. The Congress has specifically prohibited the NPS from permitting activities in derogation of park values. . . . I am sure we are sanctioning a use that we have no legal authority to permit. To close out the use and occupancy at the expiration of the current permit would be the proper course of action for the preservation and protection of park values. [50]

Early in June 1986, Donald Dayton, who was then the Acting Regional Director, notified the Associate Director for Park Operations in Washington of the "potentially sensitive political issue" of the decision not to extend Hinson's special permit. He noted that Hinson would be given four months past the June 30 expiration date to vacate the Pine Springs buildings, that Congressional offices would be notified of the decision via letters dated June 20, and that Hinson would be notified on June 26. He reviewed the unfavorable news coverage that occurred in 1982 and warned that public controversy was again possible. [51]

The promised letters to the Congressional delegation recalled the original controversy, told of the annual renewals of the special use permit, and described the only legal way in which the Pine Springs Cafe could continue to operate: as an official concession that met public health and liability insurance standards and for which a fair market rent was paid. Smith's letter also described the proposed four-month extension of time to permit Hinson to vacate the buildings and the compensation for moving expenses for which she was eligible. Copies of the letter went to Senator Bentsen, Senator Phil Gramm, and Congressman Ronald Coleman. [52]

Smith's letter to Hinson established November 1 as the final date for vacating. He pointed out that he had no legal authority to continue the special use permit and offered no alternatives to her. Finally, he reiterated her eligibility for reimbursement for moving expenses. [53] A month later Smith responded to a request from Hinson and sent copies of the letters in which Dunmire had committed the Park Service to providing water and access to her property adjacent to the park. He reassured her that the Park Service intended to honor these commitments. [54]

In September park managers released the news that funds to complete documentation of the history of the buildings on the Glover tract would be available in 1987. The news story was released September 19 and appeared in the Carlsbad Current-Argus on September 22. It contained the announcement that Mary Hinson's special use permit had not been renewed. In spite of what appeared to be orderly progress toward the park's final possession of the Glover buildings, Hinson was not ready to give up. Less than a week after Smith issued his news release about the Glover tract, Secretary of the Interior Donald Paul Hodel overturned the Regional decision to not renew Hinson's special permit. According to the story that appeared in the Washington Post on September 25, Hodel had learned of Hinson's problem from Bentsen and had decided to permit Hinson's occupancy for five more years. [55]

Smith accepted defeat with grace. In March 1986 he complied with arrangements made after Hodel's decision and sent the Congressional delegation copies of the "Letter of Authorization," which had been approved by the Department of the Interior, to permit Hinson's continued use of the cafe until January 1, 1992. The authorization stipulated that no capital improvements could be made to the building and that repairs affecting the historical integrity of the cafe were to be coordinated with the Texas Historical Commission. (In his cover letter Smith reported that the Texas State Historic Preservation Officer had already been consulted about a roof repair for the cafe.) The authorization also required Hinson to meet applicable state health and safety codes and to assume liability for damages to third parties which were incurred in the cafe. Hinson would continue to pay a nominal rental fee for the building. After obtaining the new agreement, Hinson spent little time at the Pine Springs property. She lived in El Paso and the spouse of one of the employees of the highway department operated the store for her. [56]

When the Texas State Historic Preservation Officer declared the Glover buildings eligible for listing in the National Register, park managers were mandated to preserve the buildings, at least until they had been thoroughly documented. The agreement reached with Hinson in 1987, which involved the State Historic Preservation Office in decisions about repairs to be made to the cafe, gave the park managers somewhat more leverage in assuring that the integrity of the buildings would be retained until they could be fully recorded. However, since the Park Service did not intend to retain the buildings, repairs to the cafe or any of the other buildings in the complex would force expenditures which would not have been incurred if the Park Service had obtained possession of the buildings in November 1986. In any event, the cordial but distant relations between Hinson and the Park Service made management of the cultural resources at the Glover site difficult.

By 1987 three superintendents had dealt with the problems associated with the Glover property. Donald Dayton's goals had been to gain the confidence of Walter and Bertha Glover and establish a good relationship with them. In an interview in 1987, Dayton concluded that he and other park personnel had succeeded in those objectives. Ralph Harris, who became Area Manager after Dayton left the Superintendency, concurred with Dayton's assessment. The next Superintendent, William Dunmire, faced a more difficult task--dislocating Mary Hinson from the property. He did not succeed. Looking back at the events related to the Glover property that took place during his Superintendency, Dunmire recalled that it was a "painful situation. We took some big knocks." He also believed, in retrospect, that the lease extension did not hurt the park and "the whole deal wasn't worth the negative publicity [it generated]." His hindsight suggested that the negative publicity might have been circumvented by a better public relations plan. The next Superintendent, Richard Smith, tried a better public relations plan. He warned the Congressional delegation of his plans to gain possession of the Glover property and even had the support of the Carlsbad Chamber of Commerce and staff members of the Current-Argus in his effort. But he was defeated by larger politics, the kind with which no Park Superintendent or Regional Director could argue. The role of the new Superintendent, Karen Wade, will undoubtedly be similar to Dayton's, to wait patiently until 1992, following the mandate to care for the buildings on the property and trying to maintain good relations with Mary Hinson.

Management of the park's cultural resources placed decision-makers in the unenviable position of having to identify and evaluate the resources, then wait for considerable periods of time until funding became available for the additional research that was needed to rationalize the management process. By 1987 most classified historic structures had been stabilized and could be held for a number of years without further serious deterioration. In addition, two of the park's historic resources had been successfully adapted for reuse. Managers did well with their small budgets. In 1987 the prehistoric resources also were in holding patterns, but more precariously so, because they were less easily monitored than the historic structures. After fifteen years of operation, resource managers had fulfilled the requirements of the law as well as funding had allowed, but it appeared that much more time might pass before they acquired more sophisticated management tools.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

gumo/adhi/chap10.htm

Last Updated: 05-May-2001