|

Guadalupe Mountains

An Administrative History |

|

Chapter III:

THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF WALLACE PRATT AND J. C. HUNTER, JR.

The Role of Wallace Pratt

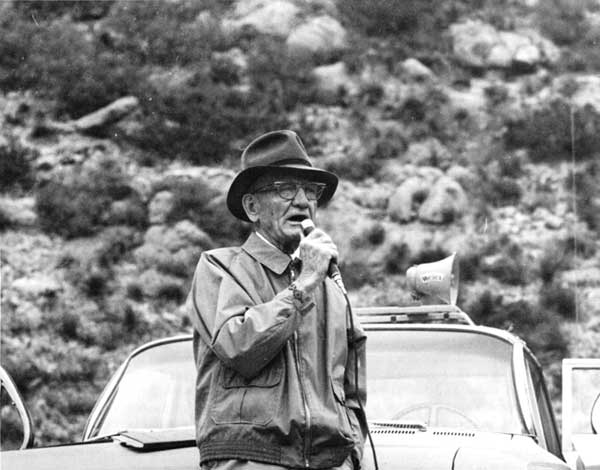

Wallace Pratt, the man Roger Toll had described in 1934 as being uninterested in a park in the Guadalupe Mountains, ultimately became the man who brought the decades of hopes for a park to reality. Pratt was a geologist--the first employed by Humble Oil Company. He was one of the new generation of scientists who used their knowledge of the origins of oil and micropaleontology to rationalize oil exploration. A slight and gentle-mannered man, Pratt once called himself a "never prepossessing 115-pound Kansas Yankee." He loved nature, but especially he loved rocks. In later years, when an interviewer questioned Pratt about the origin of the name of McKittrick Canyon, he confessed that because he was "more interested in rocks than men" he merely accepted oral tradition that attributed the name to an Army officer, Felix McKittrick. Until his death in 1981, Pratt spoke and wrote tirelessly and eloquently of the geological history revealed in the canyons and escarpments of the southern Guadalupes, always seeking to imbue some of his love of natural history in his listeners and readers (see Figure 9). [1]

In 1921, Pratt was in the area of Pecos, Texas, investigating oil leases for Humble Oil. One enterprising real estate agent captured Pratt's attention by offering to show him "the most beautiful spot in Texas." After driving the dusty and rough 100-mile round trip from Carlsbad to see McKittrick Canyon, Pratt had to agree with the agent's appraisal of the land. He was fascinated not only by the primitive beauty of the green and watered canyon, but with the geological history exposed in the canyon walls. Pratt knew he could not purchase the property himself, so he shared his find with friends Rupert Ricker and Floyd Dodson. Later in 1921 the three entered into a partnership agreement to purchase eleven sections in McKittrick Canyon that were part of the McComb Ranch. [2]

The partners were surprised in 1925 when J. C. Hunter purchased a section of land adjacent to the western boundary of the McComb Ranch. The surprising aspect of the news was that the section contained much of the land in South McKittrick Canyon that Pratt and his friends thought they owned. Ambiguous surveys caused the confusion. Years later, as he recalled the chagrin of the partners at this turn of events, Pratt pointed out that Hunter had been building up his holdings in the Guadalupe Mountains for some time prior to his purchase of the section in McKittrick Canyon. While Pratt and his friends depended on McCombs' oral description of the boundaries of the property they purchased, Hunter was better informed. He was familiar with the surveys in the land office, and he knew that the State still held title to the section in McKittrick. Pratt believed that when Hunter learned of the purchase of the canyon land by Pratt and his friends and became aware of the scenic value of the canyon, he "simply beat [them] to it." [3]

|

| Figure 9. Wallace Pratt in 1964, speaking to members of the Roswell Geological Society who were on a field trip in McKittrick Canyon. A professional geologist, Pratt loved to tell the geological history revealed in the walls of McKittrick Canyon. He donated his land in McKittrick Canyon to the federal government to be used as a park. (NPS Photo) |

Financial reverses in 1929 caused Pratt's partners, Ricker and Dodson, to offer their shares of the property to Pratt. In 1930, with a loan from friend and financier Robert A. Welch, Pratt acquired full title to the partners' portion of the canyon land. During the winter of 1930-31 Pratt commissioned Houston architect John Staub to design a home for his family, to be built at the junction of North and South McKittrick Canyons. [4]

Staub designed a house that would fit the wilderness setting of McKittrick Canyon. The Stone Cabin, as it came to be known, was built entirely of native stone and comprised four rooms: two bedrooms, each with its own bath, a kitchen and a living area. The stone came from a quarry on the McComb ranch. Four men--a civil engineer, a carpenter, a stone mason, and a laborer-- accomplished all phases of construction, including the stone quarrying. Until 1945 this cabin served as the summer home for the Pratt family. [5]

Pratt's scientific approach to oil exploration served him well and allowed him to retire a wealthy man. He rose quickly in Humble Oil, becoming a member of the board of directors and then a vice president. From 1937 until his retirement he lived in New York City and served on the board of directors of Standard Oil of New Jersey, Humble's parent company. By the time he moved to New York, Pratt was thinking of retirement and establishing a permanent residence at the Manzanital Ranch, the name he had given to his property in McKittrick Canyon. He had intended to use the Stone Cabin as a retirement home, but a flood, which trapped the family in the canyon for several days, caused him to rethink his plans. Subsequently, New York architect Newton Bevin designed the home that was built outside the canyon, on a promontory at the base of the mountain. In 1941, Ed Birdsall of Carlsbad, the man Pratt hired as his general contractor, began construction of the house. Work was interrupted, however, by World War II and was not completed until 1945. [6]

The Ship on the Desert, the name the Pratts gave to their retirement home, was a long, single-story, rectangular structure. Centered over the main floor was a much smaller second-story "deck" room. Transverse walls of native rock, tied together by steel beams, formed six rooms on the main floor and the deck room. Other walls were glass or formed by steel studs with stucco and plaster finish on steel lath. The only wood utilized in the entire structure was in the outriggers for the roof overhang. [7]

Wallace and Iris Pratt spent fifteen years in their desert home. They enjoyed the telephone-less isolation of the Ship until the late 1950s when health considerations forced them to make plans to move closer to medical facilities. Though the Pratts had been isolated, the years of their canyon life had not been lonely. During the years that they owned the Manzanital Ranch they often shared their beautiful canyon lands with friends and with scientists who wanted to study the geologic formations and wildlife there. The years and his experiences convinced Pratt of the canyon's appropriateness for a park. However, he also recognized the need for professional management of a fragile resource.

In February 1958, after the idea of a park in McKittrick Canyon had laid dormant for some twenty years, Pratt approached Taylor Hoskins, Superintendent of Carlsbad Caverns, with his offer to donate 7,000 acres in the canyon to the National Park Service. He valued the property and improvements at more than $200,000. [8] In April 1958 a team from the Park Service inspected Pratt's property. Eight months later, on December 19, 1958, Pratt received notification of acceptance of his donation. [9]

The area the Park Service agreed to accept included 5,632 acres, which were deeded to the federal government in three parts. All of the Pratt land was acquired under Section 2 of the Antiquities Act of June 8, 1906 (16 USC, Sec. 431). The first donation of 4,942 acres was accepted December 30, 1959. The second donation, a one-third interest Wallace and Iris Pratt held in 690 acres, was accepted on December 28, 1960. The deed to the other two-thirds interest in the 690 acres, which belonged to the Pratt children, sons Houston and Fletcher, and daughter Nancy Jane Tucker, was accepted January 2, 1961. [10]

The property was accepted subject to the oil, gas, and mineral rights of the State of Texas and a lease held by Humble Oil Company on Section 14, Block 65, Township 1 South. [11] The Pratts also reserved their rental and royalty rights to Section 14 for the term of the lease as well as the rentals and royalties that might accrue from oil and gas leases on Section 11, Block 65, Township 1 South, for twenty years following execution of the deed. [12]

In later years, when some people criticized J.C. Hunter, Jr., for making a profit on the sale of his land, Pratt came to his defense. He pointed out that the Pratt family had also benefitted financially from their donation. Although they had donated their property to the federal government, the members of the family had been allowed to deduct the full commercial value of the property from their income taxes. [13]

Pratt's interest in providing the country with a park did not end with his land donation. He immediately began a personal campaign to increase the size of the McKittrick Canyon park. In February 1961, Pratt wrote a purposely provocative letter to Frank Tolbert of the Dallas Morning News to ask for his help. Tolbert, the author of a column popular among Texas nature-lovers, "Tolbert's Texas," had recently devoted one of his articles to McKittrick Canyon. Pratt asked Tolbert's support in seeking "some public-spirited and loyal Texan with sufficient means (or a group of such Texans) to buy . . . the remaining critical area not included in our recent gift, and present it . . . to the National Park Service." [14] The "critical area" to which Pratt referred was an additional 6,000 acres of mountain upland owned by J. C. Hunter, Jr., adjacent to the land Pratt had donated. If that land could be acquired, Pratt, like Roger Toll before him, envisioned the construction of a mountain highway to connect the salt flats west of the Guadalupe Mountains with Carlsbad Caverns. [15]

Pratt was not content with provoking only Tolbert; he also sent a copy of the letter to J.C. Hunter, Jr. Hunter replied quickly and applauded Pratt's letter to Tolbert. He emphasized the fact that a "wealthy benefactor" was of "prime importance" and continued to say that he believed more than 6,000 acres would be required to prevent commercial development so close to the scenic lands. Hunter also pointed out that he could not afford to sell only the scenic portion of his Guadalupe Mountains property, for much of the value of the entire ranch was tied up in the "aesthetic attraction of McKittrick Canyon." Hunter advised Pratt that on January 10, 1961, Leslie Arnberger, Chief, National Park System Planning, from the southwest regional office of the Park Service, had visited his office and made arrangements for regional staff members to survey his Guadalupe Mountain Ranch the week of May 15-20. Hunter invited Pratt to join the investigating party. Hunter responded positively to Pratt's suggestion of a parkway but he had his own ideas about the route it should follow. He preferred to see the road along the ridge-top come off the mountain along the slope of Pine Canyon and return to the U.S. highway in the vicinity of Frijole, which he believed offered a better location for development of park services. [16]

A week later, Pratt accepted Hunter's invitation to join the investigating party and responded positively to his other comments. He sent a copy of his letter to Oscar Carlson, who had become Superintendent at Carlsbad Caverns. Pratt hoped to convey to the Park Service Hunter's interest in selling his ranch for the purpose of establishing a park. [17]

Wallace Pratt continued to participate in the movement to establish a separate national park in the Guadalupe Mountains of Texas. He solicited among the circle of personal and professional acquaintances he had established during his career in the oil industry for the much-desired wealthy benefactor who would purchase Hunter's land. Pratt also testified as both interested person and expert geologist during the congressional hearings preceding the creation of Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

After the park was finally established, the Park Service continued to seek Pratt's advice about resource uses and interpretation. Recognizing his valuable knowledge of the geologic history revealed in the mountains and canyons of the southern Guadalupes, the park managers arranged to have Pratt tell on tape the story that he loved so much, about the formation of the Capitan Reef and the Permian Basin. Pratt died in 1981, but visitors to McKittrick Canyon can still hear his voice, telling the story the canyon reveals.

National Park Service Interest in the Guadalupe Mountain Ranch

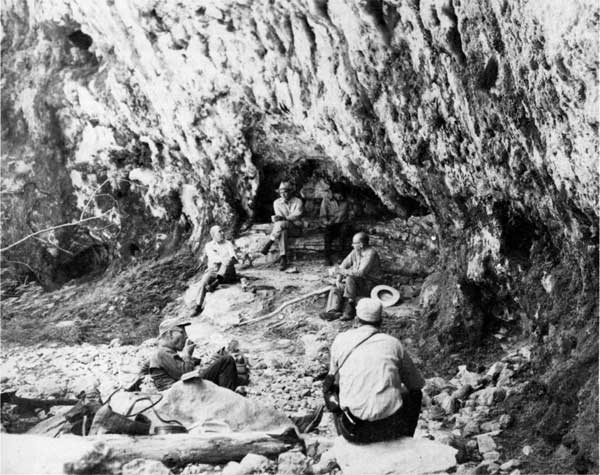

In May 1961, the team from the Southwest Regional Office of the Park Service, accompanied by J.C. Hunter, Jr., and Wallace Pratt, surveyed Hunter's Guadalupe Mountain Ranch (see Figure 10). A report to the Regional Director, issued in March 1962, summarized the investigation of the area. The group was favorably impressed with most parts of the ranch as potential park property, particularly the mountain uplands that included El Capitan and Guadalupe Peak. Echoing the long-time philosophy of the Park Service that parkland should be of little economic value, [18] the report emphasized the meagerness of economic resources on the ranch. Ground water received a "valuable" assessment, while the potential values of building stone, road material, salt, oil, and gas were minimized. The only economic utilization of the 110-section ranch was for Angora goat production. [19]

|

| Figure 10. In 1961 a team from the Southwest Regional Office of the Park Service surveyed the Guadalupe Mountain Ranch to determine its appropriateness for a national park and were favorably impressed with what they saw. Pictured above, left to right, are T. J. Allen, Regional Director; G. W. Miller, Assistant Regional Director: Noel Kincaid, foreman of the ranch; J. C. Hunter, Jr., owner of the ranch; L. P. Arnberger and Paul Wykert, Regional Office staff members. (NPS Photo) |

The report pointed out Hunter's conservation-minded management and the fact that wildlife resources had increased under his ownership. The team viewed the introduction of elk (1929), Merriam turkeys (1954), and the planting of bluegill and rout in McKittrick Creek as positive aspects of management by the Hunter family. Although Hunter had allowed the north and west sectors of the ranch to be badly overgrazed by the goats, drift fences separated this area from the scenic uplands of the mountain range. [20]

The report also included geological, biological, archeological, and historical assessments of Hunter's ranch. The geological report emphasized the uniqueness of the Capitan reef, pointing out the "remarkable display of deep-water basin deposits, of reef and reef talus, and of shallow-water shelf sediments, all formed at the same time but differing because of differences in the environments in which they originated." The botanical report emphasized the range of botanical features found within the boundaries of the ranch. The team observed ecological variations from Chihuhuan desert to Canadian zones. Native animal life included small and large mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles. Archeological resources, largely cave sites, included evidence of long-term occupancy beginning 6,000 years ago and continuing through the time of the Mescalero Apaches. Historic resources included remnants of the Butterfield Trail stage station. [21]

The survey team found the climax-type vegetation existing in the ridge area worthy of protection from overuse and fire. They also suggested that the varied terrain offered the opportunity for roadless sections as well as areas developed for heavy public use. One possible form of development suggested was a ridge road, similar to the ones envisioned by Toll, Pratt, and Hunter. The accessibility of the property seemed problematical, and the team recommended access from the east via U.S. 62-180. The team concluded that the scenic and scientific values of the Guadalupe Mountains, particularly in South McKittrick Canyon, were worthy of serious consideration as park lands and would "round out" the land donated by Pratt. [22]

The introduction to the study revealed the attitude toward acquisition of the Hunter land that would prevail for nearly a decade: that Hunter had little choice but to wait for the government to buy his land. The investigators believed Hunter had few potential buyers for his land and that there was ample time for the Park Service to consider acquisition. [23]

In July 1962, A. Clark Stratton, Acting Director of the Park Service, made the results of the investigation of Hunter's ranch known to Interior Secretary Stewart L. Udall. Stratton pointed out that the area recommended for park status involved only 27,000 of nearly 72,000 acres that Hunter wished to sell for $1,500,000. Stratton also anticipated that in this situation Udall might suggest that Hunter exchange the acreage for which the Park Service did not wish to pay for other land in the public domain. In this regard, Stratton reminded Udall that Texas contained no public domain, thereby making it necessary for Hunter to exchange for land in some other state if the idea of an exchange were pursued. Stratton concluded by noting that the acreage deemed undesirable by the Park Service was generally unattractive and unproductive, that the U.S. Forest Service had already indicated its lack of interest in the property, and that it would be difficult to sell apart from the rest of the ranch. [24]

Udall recognized the limitations of the situation and the need to purchase all of Hunter's property, not just the scenic parts. In response to Stratton's report, he began soliciting benefactors who might purchase Hunter's property and donate it to the federal government. On the recommendation of Hunter's agent, Glenn Biggs, Udall contacted the heads of three philanthropic organizations located in Texas: the Braniff Foundation, the Robert Welch Foundation, and the Amon Carter Foundation. Although records do not contain the responses to Udall's solicitations, none of the foundations was involved in subsequent negotiations for the park lands. [25]

J. C. Hunter, Jr., and Glenn Biggs

After his death in 1945, Judge Hunter's property had passed to his wife and son, J.C., Jr. The Hunters had continued to buy land in the Guadalupes and to manage it conservatively. By 1961 the Guadalupe Mountain Ranch had reached a total of some 72,000 acres.

J.C. Hunter, Jr., like his father, was a well-respected civic leader. During the early 1970s he was mayor of Abilene, Texas, for six years. Besides being involved in the family oil business, he served on the boards of Hardin-Simmons University, the Baptist Foundation of Texas, the Independent Petroleum Association, Citizens National Bank of Abilene, and the West Texas Utility Company. Similarly, like his father, he was outgoing and generous and enjoyed sharing the Guadalupe Mountain Ranch with friends and associates. However, after the visit by the Park Service reconnaissance team in May 1961, Hunter began seriously considering the sale of the ranch. In September 1961, without knowing the outcome of the Park Service study, Hunter put the ranch on the market and hired Glenn Biggs, a partner in the Abilene, Texas, brokerage firm of Millerman and Millerman, to represent his property. [26]

Glenn Biggs played an important role in the creation of Guadalupe Mountains National Park. Biggs was an ambitious young man; after graduating in 1956 from Baylor University he had been the assistant manager of the Abilene Chamber of Commerce for three years before going into the real estate business. The untiring effort he exerted from 1961 to 1965 in Hunter's behalf must not be overlooked. Although Biggs stood to make a substantial commission on the sale of the property (5 percent of $1,500,000), he was also strongly committed to the idea of a park. Biggs was a latter-day "booster." Some people considered him over-zealous because his good intentions often led him into territory other than his own. [27] In spite of criticism, however, he continued to struggle through the legislative red tape that was necessary to create Guadalupe Mountains National Park.

Biggs donated his papers from the Guadalupe Mountain park years, 1961-65, to the archives of Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. The thousands of pages there testify to reams of letters Biggs wrote and answered, thousands of miles he traveled, and uncounted days and nights he spent pursuing park status for the Hunter ranch.

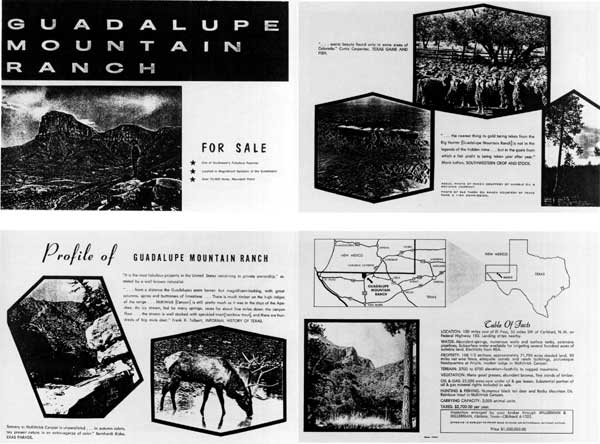

Soon after Biggs took on the sale of Hunter's ranch, he published an attractive colored sales brochure filled with photographs of the ranch and containing quotations from naturalists, government officials, and other writers about the beauty of the property (see Figure 11). The brochure, however, was only a tickler. Serious prospects also received a hefty notebook full of information about the ranch. Biggs utilized the network of real estate brokers of which he was a part to search for a client of substantial means who would be interested in the type of property the ranch represented.

Between October 1961 and January 1963 Biggs negotiated with several persons who appeared seriously interested in the Hunter property. However, none of them made Hunter an offer. In June 1962, when Hunter learned about the favorable report the Park Service team had made about the ranch, he indicated his willingness to sell the land to the federal government. [28]

The stage was set for the legislative process to begin. The Pratts and the Hunters, people whose lives testified to their belief in the revitalizing qualities of mountains, canyons, and nature left to its own devices, stepped down. They recognized the unique value of their lands and they trusted the federal government to preserve that value. The final decisions about how their land would be preserved and developed fell into the hands of businessmen, politicians, and environmentalists. The interests of all of these sectors would be expressed at various times and in various ways in the ensuing decade and the balance of power would shift from the hands of the developers to the hands of the environmentalists. Guadalupe Mountains National Park was created at a time when the values of Americans were broadening. Material gain continued to be important to most people, but they were beginning to realize the nation could be bankrupted, physically and spiritually, by unrestricted exploitation and depletion of natural resources. Guadalupe Mountains National Park would be a preserve of wilderness resources, a product of the democratic system, established to enhance both the material and the spiritual interests of the nation.

|

| Figure 11. Guadalupe Mountain Ranch Sales Brochure |

The sales brochure distributed by Glenn Biggs to advertise the sale of J. C. Hunter, Jr.'s, Guadalupe Mountain Ranch emphasized the wildlife and scenic resources of the ranch and gave secondary importance to its economic value as a working sheep ranch. Biggs and Hunter knew that the property was more likely to be purchased by a wealthy person interested in a private hunting or nature preserve than by a working rancher. (From the Glenn Biggs Collection, Southwest Collection, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, Texas)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

gumo/adhi/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 05-May-2001