|

Hopewell Culture

Amidst Ancient Monuments The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio |

|

CHAPTER ONE

A Brief History of the Hopewell Culture

The Hopewell Experience

While humans have been in southern Ohio's Scioto River Valley for more than eleven thousand years, the area's natural history evolved over countless eons. The Teays or Deep Stage River helped shape this valley when ice jams assisted in the deposition of glacial debris from a succession of moving ice sheets. The contemporary Scioto River flows south from the relatively flat central Ohio region into Ross County where it meets the western foothills of the Appalachian Highlands. Framed by 600-foot high rocky hills, the valley stretches into a three-mile-wide fertile plain.

The natural attributes of the area easily attracted early humans who first arrived in North America from Siberia via Alaska's Bering Land Bridge. In search of large game animals, these Paleo-Indian hunters roamed ever southward, arriving in Ohio more than eleven thousand years ago. Along with the fossilized bones of their prey, virtually the only remaining archeological evidence of Paleo-Indians are their fluted points. More evident are habitation sites related to the Archaic hunters and gatherers who depended in part upon mussels, hunting, and gathering. By 1000 B.C., these groups developed a variety of Woodland cultures known for their agricultural economy.

One of these Early Woodland period cultures, the Adena culture, emerged about 300 years before Christ and subsisted through about A.D. 200 in some areas. These prehistoric people cultivated squash, sunflowers, marsh elder, and knotweed, but supplemented their agrarian existence with hunting and other gathering activities. They typically used pottery, copper, mica, and shells. Most of what is known about the Adena derives from their mortuary practices, which took two forms. While most were cremated, specific individuals were selected to be encased in log tombs that were subsequently covered by mounds of dirt. Adjacent burials, and even burials on top of previous mounds, resulted in even larger mounds. While some Adena mounds have been identified at almost ninety feet high, most are small containing single burials, can be clustered in one area, and could even include some of the various circular earthworks seen in southern Ohio. [1]

|

| Figure 2: An example of Hopewellian skill, a prehistoric craftsman fashioned this human hand out of mica. (NPS/no date) |

The Hopewell, developed at least in part out of Adena predecessors, because many Hopewellian cultural practices show continuity with the Adena. [2] The Hopewell perfected the use of copper to make intricate handicrafts, and are credited with achieving the highest level of Indian artisan culture in the prehistoric Eastern North America. Southern Ohio served as the cradle of Hopewell culture, and although sites have been identified throughout the "Old Northwest" and as far west as Nebraska and Kansas, they do not exhibit the high level of achievement found in Ohio. Ross County alone features an amazing collection of Hopewellian monuments, the most impressive of which include: the Seip, Baum, Frankfort, Chillicothe, and Harness groups (two circles and a square); the Dunlap and Hopeton groups (a square and circle, with linear parallel walls); the High Bank Group (a circle and octagon, with divergent parallel walls); the Hopewell Group (two squares and circles); the Cedar Bank Group (a square with a riverbank on one side); and the Junction and Blackwater Groups (numerous squares and circles). The Mound City Group, although smaller and less complex, has the greatest concentration of mounds, and is believed to have served at least in part as a mortuary facility.

The earthworks themselves indicate an advanced, well-organized society. Objects found with burials in the mounds indicate the Hopewell did not limit themselves to Ohio or the surrounding region. Hopewellian trade networks stretched to the Gulf of Mexico for sea shells, North Carolina's Blue Ridge Mountains for mica, the Chesapeake Bay for fossil shark teeth, Michigan's Isle Royale and Keweenaw Peninsula for copper, and Yellowstone for obsidian. Agrarian practices are thought to have included maize as a minor garden plant, perhaps the first introduction of this foodstuff in prehistoric North America, but this point remains in dispute.

As with the Adena, few habitation sites have been found and examined, and much of what is known about the Hopewell comes from archeological evidence related to their burial practices. Some were buried in the flesh, others were cremated. Burials saw the body placed on bark, netting, or animal skins along with ornaments and implements. A covering of logs or stones encompassed the corpse, which in turn received a covering of bark or poles with a mound of earth topping the arrangement. While some burials were alone, others appeared in groups, usually in limited numbers. Cremations occurred in an area designated for the purpose. Posts were usually placed in a circle around the special site. Within these "charnel houses," [3] preparers molded damp clay into a basin within which the remains of their dead were cremated. The basins measured six by four feet, and nine inches deep. Following cremation, ashes were deposited nearby within the shrine where burial offerings were sometimes also ceremoniously placed either intact, broken, or mutilated. After the primary purposes of the charnel house were fulfilled, the Hopewell burned it and subsequently began covering it with dirt, erecting earthen monuments over the site, either in one continuous stage or a series of stages, perhaps separated by sand and/or gravel. Only at Mound City and Tremper groups were cremations reserved exclusively for those sites.

Because of Hopeton's peculiar positioning across the Scioto River from the Mound City Group, archeologists have tried to explain a linkage between the two sites. However, the nature of the relationship between them is entirely speculative. The entire complex featured mounds of varying appearance. The smallest mounds had but one burial and measured about three feet high and twenty-five feet across. One mound with one burial, measured seven feet high and fifty-five feet across, and had three crematories. Another mound at eight feet high and sixty feet across, featured twenty-two burials and one crematory. Anthropologists believe that most of the community took part in constructing the earthen monuments to the dead. People excavated dirt adjacent to the walls of Mound City Group. Traces of eight pits have been documented, the largest depression measured 200- by 125- by 18-feet. The larger mounds featured ten to twenty-inch-thick caps of gravel excavated from the nearby river.

Around A.D. 400, Hopewell lifeways changed. Because the Hopewell left no written records and aboriginal peoples present at the time of European contact were as mystified as anyone about the "Moundbuilders," anthropologists can only speculate as to their demise. Disease, dwindling food supplies, changing climate, and pressure from outside enemies have all been suggested as reasons why the Hopewell culture changed to a pattern known as "Late Woodland" or "Mississippian." [4]

The Scioto River Valley did not become vacant. Descendants of Hopewellian populations remained. Other aboriginal groups migrated into the area from the north and used the curious landscape features to bury their own dead, hence the name given to them, the "Intrusive Mound" people. By 1000, a people known as "Fort Ancient" occupied the valley. They were principally sedentary maize agriculturalists. When village food storage pits were emptied, sometimes the pits were used to hold debris and even human burials. Some ground-level burials were covered by small mounds, but most were in stone-lined depressions below grade. The Fort Ancient ended their occupation by 1650, perhaps in part driven away as a result of warfare with the Iroquois who had access to Dutch guns.

Shawnees were the occupiers of western Kentucky, through Ohio, to Pennsylvania at the time of contact in the eighteenth century. Two of the five Shawnee clans settled in the Scioto valley. Immediately prior to the American Revolutionary War, the Tshilikautha [5] clan settled at the present-day site of Frankfort. The clan's Anglicized name, Chillicothe, emerged near the end of the century. The Pikewaa clan's settlement lent its name to both Pickaway County and Piqua, Ohio. Shawnee chieftain Blue Jacket participated in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. Shawnee leader Tecumseh fiercely resisted American migration into their territory. Following the U.S. victory at Fallen Timbers, the Treaty of Greenville in 1795 extinguished American Indian claims in the Scioto valley and most of Ohio. A new nation conceived and ruled by Anglo-European men, the United States of America began expanding beyond the Appalachians, seeking to impose its culture and military dominance over native peoples. With vast continental resources to exploit and lands to explore, the prehistoric mounds stood as powerful curiosities to spawn myths and legends among white Americans. Nowhere was this intense interest more manifest than along Ohio's Scioto River. [6]

Squier and Davis at Mound City Group

American settlers first reached the area in 1796 when Nathaniel Massie of Virginia arrived four miles south of the Mound City Group to lay out the town of Chillicothe. Virginia laid claim to the entire region as part of its trans-Appalachian military district reserved for Revolutionary War veterans. Two years later, a 1300-acre section containing the mounds was surveyed for William Davies, but title soon transferred to Massie. As early as 1808, a Chillicothe newspaper reported on the peculiar collection of mounds in the vicinity, and news of their existence spread further in 1809 when a New York medical journal reported on them. Most local people were more concerned about surviving the rigors of frontier life than the mounds. During the War of 1812, Americans built Camp Bull, a drill field and prisoner-of-war camp for British soldiers captured on or near Lake Erie. It stood north of Chillicothe on the Scioto River's west bank about two miles from the mounds. As the local community which served as Ohio's first capital continued to expand, Nathaniel Massie subdivided his holdings and following his death, Massie's heirs sold-off his tracts. In 1832, George Shriver purchased the area including the Mound City Group, and the Shriver family held title to the land until 1917. [7]

Exploration of the mounds came in 1846 when Ephraim George Squier and Edwin Hamilton Davis conducted an extensive investigation. Both men were amateur archeologists who explored similar Ohio antiquities from 1845 to 1847. Squier, a New Yorker, was a self-educated journalist who arrived in Chillicothe in 1845 to serve as editor of the Scioto Gazette. Following his association with Davis, Squier went on to explore antiquities in Central and South America, becoming a respected authority. Davis, a native-born Ohio physician, had a life-long interest in the earthworks and mounds of his native state. Practicing medicine in Chillicothe, he joined with Squier to document and excavate antiquarian sites throughout southern Ohio. In all, they opened more than two hundred mounds and examined approximately half that many earthen enclosures. [8]

Davis, who sought financial assistance from Eastern friends, felt an urgency to accomplish the important scientific work promptly. Acknowledging the advancing depredations of American farmers, Davis wrote, "Whatever is done to arrest from destruction the works of a former age and peculiar people must be done quickly as hundreds are yearly ploughed into the earth by our money loving tillers of the soil." [9]

|

| Figure 3: Edwin Hamilton Davis. (Collection of the Ross County Historical Society) |

|

| Figure 4: Ephraim George Squier. (NPS) |

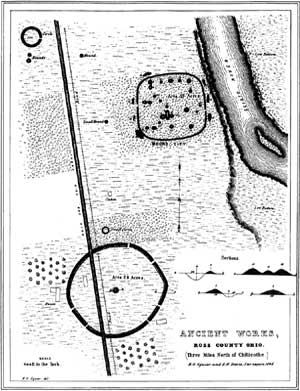

Squier and Davis's work at the mysterious collection of mounds three miles north of Chillicothe resulted in their naming the site "Mound City." From Mound Eight alone came a cache of two hundred stone-carved animal and human effigy pipes. It evoked a sense of wonder from the world's scientific community and the significant find soon became called the "American menagerie." Many marveled at the skill and anatomical level of detail exhibited by the prehistoric artisans. Squier and Davis acknowledged Mound City's variety and number of artifacts as the most significant in the Scioto Valley. In the section devoted to "sacred mounds," sixteen of eighteen pages concentrated on Mound City where they reported cremated burials along with pipes, mica symbols, various copper objects, obsidian knives, and freshwater pearls. [10]

Professional resentment clouded Squier and Davis' relationship. Davis, believing himself alone to be the true trained scientist, resented the top-billing Squier received and his own designation as an "explorer." Because of Squier's artistic graphic abilities and journalistic expertise, American intellectuals credited Squier in the fall of 1847 with conducting the primary research and preparing the forthcoming jointly-authored book. Angered by an early review of the manuscript in which kudos were heaped on his "junior partner" E. G. Squier, Davis conveyed his bitterness to a friend. Davis noted that Squier, who knew nothing about ancient earthworks prior to moving to Chillicothe, spent considerable time away from the project during their partnership, editing the weekly newspaper, reporting on the Ohio Legislature's lower house for one winter, and serving as its clerk during the previous session. "No where has he had the time to do everything," exclaimed Davis.

No, this Herculean labour has required years as you well know. When he came to Ohio, he found me engaged in these researches, with much experience, and a large store of facts already accumulated, and one of the best collections of antiques from the mounds in the Western Country. At this stage of the researches, Mr. S[quier], having some tasks for these subjects, proposes to join in as the junior partner, to continue the investigation. As I was very happy to find any one who would sympathize with me in my unique pursuits, I accepted his offer. He came into the firm bringing a ready pen, a skillful pencil, with some knowledge of surveying.

At this point, Squier devoted much attention to the excavations. Davis continued his defense, stating:

We then continue to open mounds, survey works, purchase authorities, with much vigour for two years (and almost entirely at the expense of the senior partner). At the expiration of this time, the junior partner takes up his abode in the library and cabinet of the senior, where they both toil almost day and night for many months producing the work in question. Now who is entitled to the most credit. I am of a temperament to bear most things, but this is beyond all forbearance. [11]

By the time their book saw publication, Davis, embittered and feeling betrayed, parted company with partner Squier. Their efforts came to public scrutiny in the first volume of the Smithsonian Institution's series Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge under the title Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley: Comprising the Results of Extensive Original Surveys and Explorations. This 1848 book is credited as a milestone in the early technical history of professional archeology. Journalist Squier did indeed prepare the narrative, survey drawings, and publication layout. While Davis funded their work and provided his past experience and library to the effort, the physician also undertook the meticulous task of restoring and piecing together fragmented artifacts numbering in the thousands.

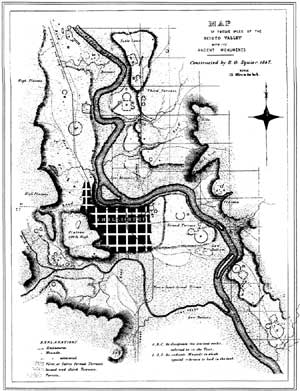

Their exploration and excavations were extensive in the Ross County-Scioto River Valley region. One of Squier's maps of a twelve-mile Scioto River segment, depicted the following "ancient monuments:" Dunlap Works, Cedar Bank, Hopeton Works, Mound City Group, Shriver Works, Junction Works, Chillicothe East, High Bank, and Liberty or Harness Group.

|

|

Figure 5: 1846 Squier and Davis drawing of

Mound City and vicinity. (Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi

Valley) (click on image for larger size) |

|

|

Figure 6: Squier's 1847 "Map of Twelve

Miles of the Scioto Valley with its Ancient Monuments." (Ancient

Monuments of the Mississippi Valley) (click on image for larger size) |

Squier and Davis's association became irreparably damaged not simply by arguing over their individual contributions to Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, but they disputed ownership of the excavated antiquities as well. Davis, scorning Squier's claims, took the bulk of artifacts and left Chillicothe n 1850 for New York where he also pursued archeology along with his medical profession.

Within a year, Davis began to search for a buyer for all his artifacts, and sought in vain for an American philanthropist or institution to keep the collection intact and at home. In preparation for the sale, Davis commissioned artist James Plunkett to paint ninety-two watercolors, including some of artifacts from the Ohio explorations, and published them along with his narrative descriptions in a prospectus entitled Sketches of Monuments and Antiques Found in the Mounds, Tombs, and Ancient Cities of America. The cover reveals a Plunkett watercolor of Mound City. In 1858, he found a temporary repository for his collection at the New York Historical Society.

In 1863, William Blackmore, a British patron of anthropology, informed Davis that if he failed to sell the collection in America where it rightfully belonged, Blackmore would buy it. In February 1864, Davis wrote Blackmore:

This is to notify you that circumstances compell me to avail myself of the privilege contained in our agreement to withdraw my collection on paying the amount advance with interest to date. It is hereby necessary for me to say that I most profoundly regret its going abroad and [?] being [?] to this country. Yet it affords me some sonsolation to know that foreigners and strangers do appreciate a collection containing specimens showing the highest degree of art yet developed in the stone age of this or any other continent. [12]

|

| Figure 7: Frontispiece for "Sketches of Monuments and Antiquities" by Edwin H. Davis, 1858, depicting Mound City Group. (NPS) |

Lamenting the fact that no American buyers were interested, Davis accepted Blackmore's payment of ten thousand dollars and represented himself as its sole owner. The collection in England became known as the "Davis Collection." Nevertheless, thanks to Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, it was already popularly known in the United States as the Squier and Davis Collection.

Blackmore took the collection to Salisbury, England, where

he established the Blackmore Museum dedicated to ancient European and American man in September 1867. The loss of the collection was soon lamented in the U.S. intellectual community. However, Smithsonian Secretary Joseph Henry convinced Davis to make plaster-cast duplicates of specific artifacts prior to the sale. Davis and two artists made molds and produced three complete sets of artifacts: one for the Smithsonian in 1868 for study purposes, the second to the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology at Harvard University in 1871, and the third to the American Museum of Natural History in 1874. The last transaction also accompanied purchase of thirteen Mound City pipes owned by Squier. Finally, the Smithsonian purchased Davis's intricate molds in 1884. Never reconciling since their close Ohio association in the mid-1840s, both Squier and Davis died in the spring of 1888. [13]

Although their relationship ended in bitterness, both men contributed substantially to the development of professional archeology. Their work together at Mound City perhaps ranks highest on their list of lifetime achievements. As the highlight of Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley, it represented the first systematic, scientific analysis of prehistoric sites using guidelines and techniques still in use more than a century later. The intricate artifact drawings, mound cross-sections, and site plans were innovative and set the standard for future work. Also useful was their classification system based on function such as burial places, effigies, fortifications, building platforms, and so forth. [14] Following destruction of much of Mound City by the early twentieth century, this important record served as the basis of a succession of professional archeological investigations and reconstructions at the site. Without the 1848 Smithsonian publication documenting and speculating on the meaning and significance of such sites, the degradation would likely have resulted in total obliteration of Mound City and related areas.

Mythology of the Moundbuilders

Speculation as to the origin of the prehistoric earthworks began with the arrival of the region's first white settlers. They viewed with wonderment walls from five to twelve feet in height shaped in the form of rectangles, squares, octagons, circles, and ellipses. The area which these earthworks covered ranged from one to as many as two hundred acres. In the Ohio Valley alone, more than ten thousand mounds dotted the landscape. Digging into the conical-shaped mounds, settlers found burials and a wide assortment of prehistoric grave goods. From the start, virtually no one concluded that the immense earthworks could have been the result of aboriginals. In the view of whites, American Indians did not possess the skill, intelligence, or work ethic to produce such marvels. Rather, to whites, American Indians represented a savage culture which had to be swept aside for the inevitable advancement of civilization. Another rational solution had to be found concerning who built the wide array of earthworks in the eastern United States.

Squier and Davis contributed to the Moundbuilder speculation as they believed Indians were mere hunters, unable to construct such prehistoric earthworks. In the aftermath of Squier and Davis's work, ongoing public debate raged for decades. The imaginative result, the myth of the Moundbuilders, ranged from the romantic to the nonsensical. Whites looked to their own past and selected previous civilizations which also engaged in earthworks and credited them with somehow performing similar feats in the Americas. Mythmakers selected the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, Hindus, and Vikings as the ancient Moundbuilders. Others thought Adam and Eve inspired the first Moundbuilders, followed by Noah and his offspring. Still others were convinced that the mighty Aztecs strayed into the area to build the mounds. Whatever the origins of this Moundbuilder race, many were convinced that this advanced, sophisticated culture was overrun and exterminated by the savage red American Indians. Indeed, removal to genocide conducted against the red man somehow seemed justified if Indians had done the same to the Moundbuilders. [15] Even after scientists and archeologists solved the mystery, contemporary naysayers continue to search for fantastic explanations, including beyond Earth's orbit to give credit to "ancient astronauts."

Largely to settle the public debate and quell disagreement within the intellectual community, Cyrus Thomas, head of the Bureau of Mound Exploration of the Smithsonian Institution (forerunner of the U.S. Bureau of Ethnology), began recruiting local amateur archeologists. Under his instruction, amateurs used horse-driven farm equipment to open mounds. Demonstrating how far the profession had progressed, they utilized explicit problem orientation and research design in combination with documentation standards far superior to those of Squier and Davis. By 1890, the Smithsonian program had investigated hundreds of mounds in Kentucky, Illinois, Missouri, Wisconsin, and Michigan. Thomas's findings established a solid scientific basis for crediting extinct American Indian peoples with being the true Moundbuilders of antiquity. [16]

Modern American Archeology and Hopewell Culture

Archeology began moving from an antiquarian footing to a professional discipline in the late nineteenth century. The discipline eagerly embraced Darwinian evolution. In the U.S., Moundbuilder studies were eclipsed by the impressive Southwestern ruins. Denied a glorious prehistoric past, American enthusiasm waned with the perception that innately primitive and therefore inferior native peoples had not advanced beyond the Stone Age and were culturally static. [17] Reflecting other professional organizations, the Archaeological Institute of America, founded in 1879, had an obligatory North American bent on the Southwest and Mexico, but devoted considerable fiscal resources on ancient civilizations, particularly in Greece. Eastern North America was treated like a backwater. [18] U.S. archeology embraced this practice, domestically concentrating on the Southwest, and regarded the East like a neglected stepchild, a trend that continued through much of the twentieth century. [19]

|

| Figure 8: Capt. Mordecai C. Hopewell. (Collection of the Ross County Historical Society) |

With the myth of the Moundbuilders solved, at least in the minds of archeologists and scientists, new nomenclature became necessary. Modern archeology adopted the name "Hopewell" when a rich lode of artifacts Warren K. Moorehead excavated from twenty-eight mounds on Capt. Mordecai C. Hopewell's farm near Chillicothe were prepared for Chicago's Columbian Exposition in 1893. Because the anthropology exhibit focused on the Hopewell farm artifacts, related earthworks and their cultural materials were referred to as Hopewellian beginning in 1902. In that year, the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society's (OSA&HA) William C. Mills first made distinctions between Adena, Hopewell and Fort Ancient, and applied the term "culture" to each. [20]

In the aftermath of Mills's work, U.S. archeology embraced a culture-historical ideology following 1910 as more practitioners entered the field and shared professional methods and values. Data revealed temporal changes, particularly with increasing Paleo-Indian discoveries and the reality that native peoples had inhabited North America far longer than previously believed. Prehistorical cultural groups were defined in geographical terms. [21]

Professional archeological societies and organizations became widespread in the early twentieth century, sponsoring fieldwork and publications on archeological materials and problems within state boundaries. Ohio possessed the best of these early state archeological histories. The nation's university programs also mushroomed so that by 1935, twenty-one such institutions supported research in eastern U.S. archeology. [22] American archeology was in transition from a speculative-descriptive period to one stressing classification-chronology. Archeologists concentrated on stratigraphy, seriation, and typologies as well as culture classifications. [23] Still hampering archeologists was the belief that earthworks represented the only historically recorded attainment of past societies. They remained pessimistic with the assumption that understanding of earlier eras could only be through written records or credible oral tradition. This erroneous assumption would only be shed in the mid-twentieth century as archeology matured. [24]

Among other significant excavations the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society (OHS), founded in 1885, undertook investigations at Mound City Group from 1920 to 1921. William C. Mills, assisted by Henry C. Shetrone, announced at the end of the first field season five important findings: The mounds represented communal burial places of the Hopewell; the "altars" described by Squier and Davis were not for sacrifices, but rather for cremations; the Hopewell migrated southward along the Scioto to the Tremper Mound area around Portsmouth, Ohio; the Hopewell had progressed from individualism to communalism; and the culture traded with Indians from the Carolinas and Lake Superior region. The archeologists found examples of ancient riveting and dowel pins amid a wealth of ornaments fashioned from stone or copper among which were an otter with a fish in its mouth, a bared-teeth bear, a raccoon digging in the ground, a heron eating a fish, a baying dog, frogs, and toads. Other copper items included headdresses of deer and bear, large ornamental plates, hands, turtles, beads, ear ornaments, pendants, and arrow points. Also found were large plates of mica used for mirrors, woven cloth and mats made from bark, engraved discs of mastodon tusks, obsidian spears and knives, and pipes. [25]

Another field season came in 1921. Mills and Shetrone saw their work as a valuable addition to archeology and the Mound City Group as the best example of Hopewell culture in Ohio. Mills published the findings and an impressive array of artifacts were displayed in the society's museum in Columbus. [26] Fourteen of the twenty-four mounds recounted by Squier and Davis were examined using modern archeological techniques. The effort reignited public interest in Hopewellian studies and launched a drive to preserve its remnants.

Ohio archeologists explored other Hopewell sites during the 1920s, but with economic hardship in the 1930s, Hopewellian studies slowed to a snail's pace. Unlike other states, Ohio failed to take advantage of federal relief programs to fund archeology projects, a decision that further paralyzed Ohio Hopewellian studies during and after the Great Depression. Much of the data collected by OSA&HS proved to be "disorganized and defective.... In method, theory, and scope of research [Ohio Hopewellian study] stagnated." [27] Only one publication of note appeared during World War II, and the long hiatus progressed through the 1950s. Quite the opposite was the case in Illinois, where Hopewellian study flourished and resulted in a classification of pottery that included forty types. [28]

Discovery of a sealed stratum at Folsom, New Mexico, in 1926, resulted in building a chronology of early North American human existence, but the exact placement of prehistoric peoples like the Hopewell remained in dispute. [29] Part of the problem was the lack of temporal data to understand how the Adena, Hopewell, and Mississippian cultural complexes fit. At the Midwestern Archaeological Conference held in Indianapolis in 1935, temporally independent taxonomic categories were assigned to Hopewellian artifacts. By 1939, the categories were officially referred to as the "Midwestern Taxonomic Method" or the "McKernian Classification." A conference at Andover Academy in 1941 evaluated the interface between Adena and Hopewell. Material from both conferences resulted in regional sequences found in the 1952 volume, Archeology of Eastern United States, edited by James Griffin. [30] By examining ethnological and archeological evidence in concert, it became apparent that the cultures overlapped. [31]

On the eve of World War II, most archeologists held that the Hopewell dated from A.D. 1200 to 1400, and by 1949, some thought the dates could stretch from A.D. 500 to 800 or 900. [32] In 1950, chemist W. F. Libbey developed absolute dating from organic material containing carbon, giving archeology the powerful new method of radiocarbon dating. For archeology, radiocarbon and other geochronometric techniques allowed application of a universally accepted chronology that permitted the duration as well as relative order of subsurface archeological materials. [33] Most importantly, the new scientific tool began to energize the field as radiocarbon dating for the Ohio Hopewell finally categorized the culture at roughly 1500 to 2000 years ago. [34]

In reaction to the seemingly mindless classifications and obsession with culture history, archeologists Gordon R. Willey and Philip Phillips, in their 1958 monograph Methods and Theory in American Archaeology, proposed a three-pronged approach to research: observation/fieldwork, description, and explanation (or processual interpretation). Among others, their argument helped spawn in the 1960s a fundamental shift of the discipline led by younger archeologists, including Lewis Binford, away from culture history to science-based archeology. Hopewellian studies also reflected the larger discipline's shift to the "New Archeology." [35] Basing research on the scientific method, archeologists no longer focused exclusively on classificatory exercises, making the Midwest Taxonomic System seem suddenly archaic and obsolete. Instead, a whole new world of empirical data from other science-based disciplines became available for scrutiny and use.

At the onset of this intellectual debate, Olaf H. Prufer reluctantly undertook a Hopewellian topic for his doctoral dissertation during the late 1950s and early 1960s. In seeking professional courtesies from the Ohio Historical Society, Prufer's initial inquiry met an icy rebuke. The German-born, Harvard-educated scholar, an unwelcome interloper, had encountered the exclusive "Ohio gang" of archeologists. Nonetheless, by examining both the body of literature and museum collections, Prufer produced a reevaluation or new synthesis of the Ohio Hopewell that shattered the subdiscipline's professional complacency and lethargy. [36]

Prufer offered different views on several topics. While preferring "Hopewell Complex" to "Hopewell Culture," Prufer said the evidence suggested that the Hopewell originated in Illinois and spread through southern Indiana to Ohio where it "found its purest expression and its most intense apotheosis." [37] Prufer concurred with cultural chronologies based on seriation of artifacts, principally pottery, and confirmed by radiocarbon dating. Evidence also suggested an overlap of Adena and Hopewell cultures, and Prufer offered his own chronological ordering of Hopewellian sites, with defensive hilltop enclosures appearing in the Late Hopewell period during its terminal phase. [38] Prufer likened the classic Mesoamerican settlement pattern to the Hopewell, i.e., vacant ceremonial centers with shifting semi-permanent small settlements on the periphery, and speculated on contact between the two cultures. [39] Concurring with Prufer regarding Southwestern contact, anthropologist Edward McMichael postulated in 1961 that this Mexican diffusion originated in Veracruz and stimulated Hopewellian lifeways through the Crystal River Complex on Florida's Gulf Coast. [40]

It was through study of the well-known Hopewell trade network that archeologist Joseph Caldwell developed the concept of interaction spheres in the early 1960s. The innovative concept had universal application throughout the discipline. Interaction spheres exist when independent societies, or peer polities, exchange material products as well as information in the form of symbols, ideas, values, inventions, and goals. Within Ohio Hopewell society, the far ranging interaction sphere created an overall semblance of cultural unity while enveloping other societies and cultures within its mortuary-ceremonial or religious beliefs. [41]

Invigorated by the New Archeology, a revival of Hopewellian scholarship took place in the 1970s, culminating with the 1979 monograph, Hopewell Archaeology: The Chillicothe Conference, edited by David Brose and N'omi Greber. Fifty-four submissions covered the gambit of Ohio prehistory, including trade, domesticated plants, and settlement patterns. The conference and its regionally diverse submissions demonstrated that this branch of archeology was no longer moribund. [42]

Within Hopewellian studies, few archeologists avoided the so-called "maize debate" that emerged in the post-World War II era concerning the role of maize in the Eastern Woodlands. With the introduction of stable carbon isotope analysis in the late twentieth century, determining maize content in the prehistoric diet became possible. Such data suggested that limited maize consumption became a pattern only after A.D. 900-1000. Using the accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) to refine the radiocarbon age of maize kernels, coprolites, and archeobotanical sequences, maize did find itself in eastern North America as early as A.D. 200-300, during the Hopewell culture, but only as a minor crop. However, Bruce Smith argued that these premaize so-called hunter-gatherer people were limited agriculturalists who cultivated, stored, and processed a variety of other crops. Smith argued that archeobotanical assemblages dating from the time of Christ demonstrated the significance of seed crops for Middle Woodland/Hopewellian people. [43] Other scholars continued to disagree, asserting that hunting-gathering-fishing intensified, with small-scale horticulture augmenting that primary subsistence activity only in the late Middle Woodland. The Hopewell were thinly dispersed and seasonally mobile, and in no way tied to the land other than with their mortuary-ceremonial complexes. [44]

Papers presented at a 1992 symposium entitled "Testing the Prufer Model of Ohio Hopewell Settlement Pattern," resulted in a 1995 monograph edited by William S. Dancey and Paul J. Pacheco called Ohio Hopewell Community Organization. Presenters found that few archeologists had tested Prufer's contention concerning Hopewell habitation sites, and it became their goal to do just that. [45] The editors concurred that existing data supported the "Prufer model," but more fieldwork could yield as many as four alternate hypotheses, namely:

1. Communities are nucleated and the major settlements are villages located adjacent to the earthworks (Nucleated Sedentary).

2. Communities inhabit nucleated settlements adjacent to earthworks for part of the year but disperse seasonally to outlying camps (Semi-permanent Sedentary).

3. Communities are residentially stable, but high-ranking households (chiefdoms?) reside in the shadows of the earthworks (Central Place).

4. The households making up a community are seasonally mobile throughout the year (Seasonal Mobility). [46]

Using microwear analysis to test artifacts found in close proximity to the Newark Earthworks, Bradley Lepper and Richard Yerkes cast doubt on Prufer's hypothesis of uninhabited ceremonial centers because of the immediate presence of seasonally occupied camps. [47] Other site evidence supported their position. [48] Archeologist James B. Griffin determined that the notion of dispersed hamlets was overdrawn, and the incidents of residential debris near the earthworks could not be ignored. Griffin concluded that Ohio Hopewell settlement systems "included permanent settlements, perhaps of great size, near the Hopewell centers." [49]

Following up on the 1979 Chillicothe conference, a similar effort came in 1993, which three years later resulted in an edited book by Paul Pacheco called A View from the Core: A Synthesis of Ohio Hopewell Archaeology. True to its subtitle, it represented the most comprehensive overview of the Ohio Hopewell/Middle Woodland period. [50] While it provided new information supporting and opposing Prufer's settlement model, one of the more unusual papers examined geometric or mathematical distinctions of Ohio's earthworks. James A. Marshall, an Illinois civil engineer with an avid interest in prehistoric geometry, surveyed and analyzed Hopewell earthworks through the Midwest. He called them the "closest to a written record of a prehistoric people yet discovered north of the Rio Grande." These sophisticated people did not construct the mounds at random. Rather, Marshall established that planning and a precise knowledge of geometric principles were used along with a standard measuring unit. The mounds appear to have been built in an orderly alignment. [51]

As contemporary knowledge about the Hopewell continues to grow, the need to locate and examine habitation sites becomes more apparent. Until the late twentieth century, most work accomplished concentrated on burial sites. However, enough is known to categorize the Hopewell as the pinnacle of all mound-building cultures, and the most advanced of any north of Mexico. Robert Silverberg in The Mound Builders described the Hopewells as the "Egyptians of the United States, packing their earthen 'pyramids' with a dazzling array." Silverberg further observed,

There is a stunning vigor about Ohio Hopewell. By comparison, the grave deposits of the Adena folk look sparse and poor. Hopewell displays a love of excess that shows itself not only in the intricate geometrical enclosures and in the massive mounds, but in the gaudy displays in the tombs. To wrap a corpse from head to foot in pearls, to weigh it down in many pounds of copper, to surround it with masterpieces of sculpture and pottery, and then to bury everything under tons of earth--that is the kind of wastefulness that only an amazingly energetic culture would indulge in. [52]

In moving from myth to scientific study over the course of two centuries, Hopewellian studies have contributed to and benefitted from the maturation of American archeology. This remains true as the larger discipline experiences its current post-processualism phase, maintaining its feet in science, but also revisiting culture history. [53] Like most research, conclusions presented herein are still undergoing scrutiny as many more secrets of the Hopewell culture remain to be uncovered.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hocu/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 04-Dec-2000