|

Hopewell Culture

Amidst Ancient Monuments The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio |

|

CHAPTER TWO

Preservation of the Mound City Group

The War Department and Camp Sherman

Following Squier and Davis's excavations in 1846, the Mound City Group remained largely ignored, with the surrounding area cleared and put to the plow for the next seventy years. While many farmers regarded prehistoric mounds as obstacles and nuisances to be obliterated, the concentration of large mounds in the Scioto River Valley did not escape this fate, with most of them incorporated into fields as plowing permitted. Upon the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, Chillicotheans, as had been done in the War of 1812 at Camp Bull, used the area as a drill ground and referred to it as Camp Logan. [1]

The region's bucolic serenity came to an abrupt end following President Woodrow Wilson's April 6, 1917, call for the commitment of United States military forces against Germany in World War I. Rapid mobilization for war required federal establishment of training camps throughout the country. Chillicothe's claim of hosting such facilities during two previous wars gave it an edge over competing cities when in June 1917 it became the site of a World War I cantonment called Camp Sherman. Because farmers resisted the loss of fertile land for the low government lease price of fifteen dollars an acre, local businessmen contributed an additional five dollars per acre. Some farmers still resisted until eminent domain settled the matter. Lease terms gave the government the option to purchase all two thousand acres within five years, and the War Department began exercising that right between 1919 and 1921.

|

| Figure 9: World War I-era Camp Sherman barracks built atop a leveled mound, with cut made for adajacent roadway. (NPS/ca. 1920) |

Construction of Camp Sherman as the subsequent home of the 83rd, 84th, 95th and 96th Divisions during the wartime mobilization caused Chillicothe's population to swell from 16,000 to 60,000. Erecting a building every twenty minutes, a construction crew of more than five thousand men raced to complete the task in a matter of weeks. Amazingly, the first draftees arrived at Camp Sherman on September 5, 1917. In all, Camp Sherman consisted of two thousand buildings, including two-story wooden barracks accommodating up to forty thousand doughboys, at a cost to taxpayers of four million dollars. In essence, it represented a small city unto itself with full hospital, railroad, prison, sanitary, and farming facilities. [2]

|

| Figure 10: Cross-section of Mound 18 covered by Camp Sherman barracks. (NPS/1920-21) |

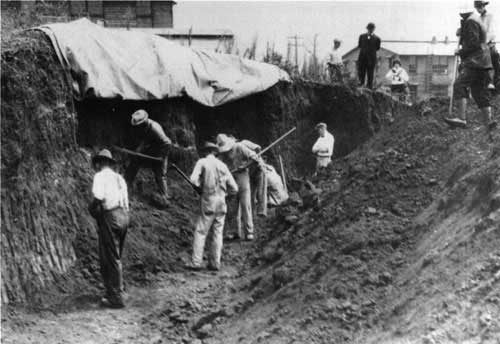

Siting of barracks in the area of the Mound City Group in Section N and O came about under the influence of local and state officials. Albert C. Spetnagel, a prominent Chillicothe amateur archeologist, appreciated the significance of the mound group and did not want to see the complex destroyed to accommodate the Army's regimented grid pattern. Among Spetnagel's friends were William C. Mills, director of the Ohio State Museum, and his fellow professionals at the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, Henry C. Shetrone and Gerard Fowke. Through Spetnagel's efforts, Shetrone, the society's curator of archaeology, successfully urged the Army to turn one barracks so as to avoid razing one of the largest mounds. Shetrone met with Capt. Ward Dabney, camp commander, to urge caution. Dabney replied: "We will construct the buildings in such a way on the mounds that they will not be destroyed. However, it will be necessary to run pipe lines through some of the mounds. Care will be taken so that specimens may be preserved intact, but if this is impossible, they will be turned over to the [society]." [3] Nonetheless, barracks, streets, and utility lines severely intruded on Mound City Group. While some of the smallest mounds had already been leveled by plowing, still others were obliterated or severely damaged by Camp Sherman construction. Most damaging was the installation of water and sewer lines because they intruded far below grade. [4]

|

| Figure 11: Excavation of Mound 7 by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. (NPS/1921) |

The November 11, 1918, Armistice brought the inevitable announcement five days later to discharge twelve thousand men from Camp Sherman. Members of the 40th Infantry were designated custodians of the facility during peacetime. The newly-formed U.S. Veterans Bureau designated the Camp Sherman medical facilities to house a permanent Chillicothe Veterans Hospital to care for wounded soldiers. By July 1920, most of the discharges were completed, and the 19th Infantry took over as custodians, leaving Camp Sherman as one of the last World War I cantonments to be closed and its buildings sold as surplus.

|

| Figure 12: Excavation of Mound 7. (NPS/1920-21) |

|

| Figure 13: Henry C. Shetrone (left) and William C. Mills (right) of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society at the Mound City Group excavation. (NPS/1920-21) |

Through President Warren G. Harding's Executive Order 3558 of October 11, 1921, under congressional authority granted on August 9, Camp Sherman Military Reservation transferred to the Veterans Bureau. The U.S. Veterans Bureau Training School opened in conjunction with the hospital and became fully operational in 1922. A Camp Sherman brick factory, operated by prisoners of war and conscientious objectors, produced the bricks which built the Chillicothe Correctional Institute (CCI) just to the south of Mound City Group. The vegetable gardens and fields maintained by prisoners subsequently were chores taken up by CCI inmates in the early 1930s. [5]

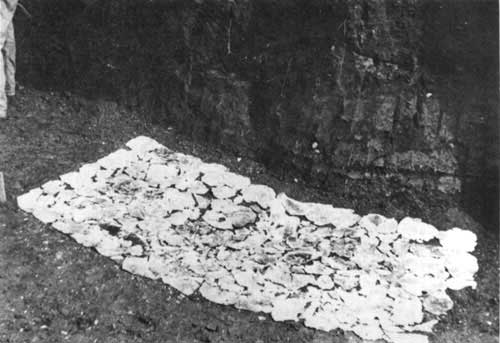

The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society undertook investigations at Mound City Group from 1920 to 1921. After a five-hundred-dollar state appropriation proved inadequate, Columbus Dispatch editor Arthur C. Johnson, along with contributions from R. F. and H. P. Wolfe, financed the fieldwork, and the newspaper further helped to secure the necessary verbal permission from the War Department and Camp Sherman commander. [6] Dr. William C. Mills, assisted by Henry C. Shetrone, also of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society, began excavating the first of eight mounds on June 16, 1920. Four of those mounds were half-covered by barracks. Mills called the 1920 season one of the most successful of his career. He told the newspaper,

The life story of this people as told in these mounds is one of the highly interesting chapters in the history of primitive civilization. No primitive people has shown such skill and perserverance in wresting from nature the raw materials needed for their purposes, nor such versatility in fashioning these materials into finished products. In the records preserved in these mounds we find a vivid picture of the strength and persistence of the forces underlying human development and urging it against odds toward a higher plane of development.

Mills said a future project would be to investigate the village site across the river to "see if there is any connection between the earthworks on the east side of the river and the burial grounds on the west side." [7]

Another field season came in 1921, as Congress, reacting to a post-war economic recession, began slashing funds for Camp Sherman operations. [8] Mills and Shetrone called their work a "rich addition to the archeology of Ohio," [9] with Mills stating that Mound City Group represented the "best example of Hopewell culture in Ohio." [10] Their work concentrated public attention on the Mound City Group and ignited a drive to preserve it. [11]

|

| Figure 14: Mica deposit at the bottom of a Squier and Davis shaft in a mound excavated by Shetrone and Mills. (NPS/1920-21) |

President Harding Proclaims a National Monument

Camp Sherman had helped transform sleepy Chillicothe into a thriving economic center in south-central Ohio. Peacetime brought about new opportunities for use of the large federal holdings to the city's north. Albert C. Spetnagel remained determined to secure a safe future for the prehistoric Hopewell mounds at Mound City Group. The impending demise of Camp Sherman forecast an uncertain future for the mounds. Spetnagel's effort gained credible support when William C. Mills announced his support for a "national park" at Mound City Group. It represented a fourth suggested use for the military reservation, the others being a training center for disabled soldiers, a reformatory for youths, and a citizens' military training grounds. [12]

Ohioans desirious of preserving Camp Sherman in any form conducted a furious letter-writing campaign directed at President Warren G. Harding, himself a native Ohioan. Many letters were sent to the president's personal physician and confidant, Brig. Gen. Charles E. Sawyer. One letter, from Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society Secretary C. B. Galbreath declared the prehistoric earthworks should be "under the custody of the state or national government."

Galbreath explicitly offered to assume guardianship of the 117-acre farm containing Mound City Group with a plan to operate it on a self-sustaining basis. He concluded by affirming, "The transfer of this farm to the custody of our society would in no way interfere with the other uses that have been suggested for the large Camp Sherman tract of land." Impressed by the society's offer, and letters of support from the Smithsonian Institution and other scientists, Sawyer pledged to dispatch his son, Dr. Carl Sawyer of Marion, Ohio, to inspect the site and deliver a recommendation. [13]

The U.S. Veterans Bureau, newly charged with Camp Sherman, did not object to use of Mound City Group for park purposes. In October 1921, bureau chief C. R. Forbes inspected the site and conveyed his decision to retain title to the land, but to allow the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society to develop a state park there. [14]

At the grassroots level, Albert C. Spetnagel lead a civic committee dedicated to ensuring the preservation of the mound group. Utilizing the auspices of Chillicothe's newly-formed Rotary Club chapter, Spetnagel's committee worked with Ohio political figures, and first proposed designation of "Mound City Group National Monument" in 1921 utilizing executive branch powers authorized by the Antiquities Act of 1906. Because there was no legislative mechanism to do otherwise short of a time-consuming act of Congress, the group strategized retaining the proposed national monument under War Department jurisdiction; however, its daily administration and operation would be as a state memorial of the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society.

Thanks to the mechanism provided by the 1906 Antiquities Act, their preservation effort easily bore fruit. On March 2, 1923, President Warren G. Harding signed proclamation 1653 establishing the Mound City Group National Monument on fifty-seven acres along the Scioto River. [15] Harding's statement called the prehistoric mounds "an object of great historic and scientific interest and should be permanently preserved and protected from all depredations and from all changes that will to any extent mar or jeopardize their historic value." [16] The 1906 Antiquities Act, originally passed to protect archeological resources in the American Southwest from vandals, gave the president the right to declare "historic landmarks, historic or prehistoric structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest... to be national monuments" anywhere in the country. Afflicted by willful abuse and damage under previous terms of federal stewardship, Mound City Group National Monument could only hope for more prudent care.

Because the federal government had not developed a statement of purpose for the country's national monuments, most remained in limbo with volunteer caretakers overseeing them. Congress allocated almost no funding for their development or care. Even upon the National Park Service's creation in 1916, America's national monuments received scant attention from the new bureau, a practice that continued until the New Deal era when the majority of such sites transferred to NPS administration and Congress loosened its pursestrings. The legacy of second-class status, however, did not quickly evaporate. Therefore, the decision to seek non-federal stewardship for Mound City Group proved fortuitous. [17]

Twenty-five days following President Harding's action, Assistant Secretary of War Dwight F. Davis executed a revocable license per the plan of Spetnagel's Rotary Club committee. The license read as follows:

The Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society is hereby granted a license, revocable at will by the Secretary of War, to care for, preserve, protect, and maintain the "Mound City Group" of historic mounds located on the Camp Sherman Military Reservation at Chillicothe, Ohio, and declared a national monument by Presidential Proclamation No. 1653, dated March 2, 1923, under authority of Act of Congress approved June 8, 1906 (34 Stat. 2251), and for that purpose to occupy the tract of land upon which they are situated, which tract was reserved by said proclamation as the site of the said monument, the site so reserved and hereby authorized to be occupied and cared for being described as follows:

All of Sections N and O, bounded on the north by East Liverpool Street, on the east by the Scioto River, on the west by Columbus Avenue, and on the south by Portsmouth Street, containing fifty-seven (57) acres, more or less.

The license is granted upon the following provisions and conditions:

1. That the said site shall be open to all people desiring to visit these mounds and shall be properly cared for and policed by the licensee without any expense whatever to the United States.

2. That no buildings or structures of any kind whatever shall be erected upon the property without the consent of the Secretary of War.

3. That no excavations of the said mounds shall be allowed, except upon permission granted by the Secretary of War. [18]

The War Department and its Veterans Bureau had little to no interest in the Mound City Group National Monument. Federal authorities were only too happy to permit Ohio officials to care for and operate the monument. By 1930, of the sixteen national monuments under the War Department's care, fifteen were expressly related to military operations significant to the nation's history. Mound City Group clearly did not fit that mold, and only remained under the War Department's purview because it was surrounded by the former Camp Sherman Military Reservation governed by the Veterans Bureau. Ohio's offer seemed like the best possible option to federal military officials perplexed by the innocuous piece of real estate known as Mound City Group National Monument. [19]

|

| Figure 15: Mound City Group restoration of the mid-1920s, looking southeast. Death Mask Mound in center features stairs and viewing platform. (NPS/ca. 1927) |

|

| Figure 16: Mound City Group restoration of the mid-1920s, looking southwest. Note a Camp Sherman-era remnant fire hydrant at left. (NPS/ca. 1927) |

Ohio Establishes a State Memorial

In late 1921 or early 1922, the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society adopted Albert C. Spetnagel's committee of Rotarians, calling it the "Mound City Committee." With Spetnagel as committee chairman, the membership included Edwin F. Cook, Charles Haynes, Dr. J. M. Leslie, Robert W. Manly, D. M. Massie, and William Allen Scott, all of Chillicothe; Arthur C. Johnson and W. C. Mills, both of Columbus; and J. R. Gragg, of Bainbridge. In his 1922 summary for the annual report, Mills reported:

The committee... has been constantly at work trying to have the Government turn over about 50 acres for a public park.... Mr. Spetnagel has carried on a very voluminous correspondence with the War Department and this department now finds that no law will permit the gift of this land to the Society but can issue a revocable license which would give the Society the right to restore and beautify the ground to be kept as a free public park.

I can see no objection to such a license as it gives us the property to have and to hold for park purposes and I fully recommend to the Society the acceptance of the license and to ask the legislature to appropriate funds for its restoration and maintenance.

During the society's fall 1922 meeting, Mills announced that Spetnagel had received assurances from the War Department of its willingness to transfer the land by revocable license. In response to Mills' enthusiastic recommendation, the society accepted the verbal offer. [20]

The 1923 presidential proclamation and subsequent transfer of Mound City Group National Monument saw the state ill-prepared to accept the offer. Inexplicably, the initial appropriation requested for mound reconstruction and site restoration was omitted from the legislature's 1923 budget. However, Director William C. Mills used other funds to purchase the Camp Sherman YMCA building remaining on the property as a prelude to site development work. [21] While Spetnagel's group, renamed the "Mound City Park Committee," supervised preliminary site work, Mills had to intervene with military authorities to save the mounds. Charged with clearing away much of what remained of Camp Sherman, overzealous workers threatened to sweep away the damaged remnants of the mounds as well.

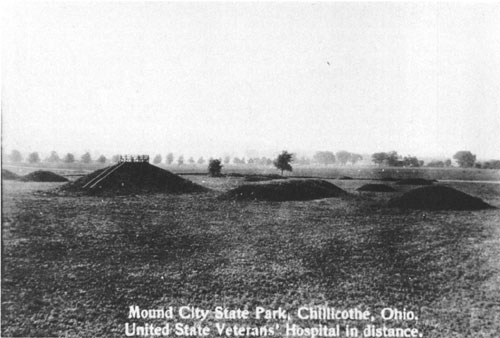

The Ohio Legislature appropriated funds to begin converting Mound City into a state memorial in 1925. On October 1, site clearing began under Henry Shetrone's supervision, and fifty wagonloads of Camp Sherman debris were removed. Workers then deep-plowed the mound area, and twenty-four mounds and their earthwork enclosure walls were located using the Squier and Davis map. Federal assistance from the Veterans Administration (newly renamed from the Veterans Bureau) came when farm manager Dean Gaddon provided a tractor, mower, horses, wagon, tools, and electrical power at no cost.

Reconstruction work based on the 1848 map continued for several weeks into the fall and resumed until completion in the spring of 1926. [22] Twenty large dead trees along the Scioto River, tall weeds, brush, along with saplings and omnipresent virginia creeper that covered the area were carried away in eighty wagonloads. Laborers again deep-plowed the area. The Mound City Park Committee sold the western part of the YMCA building containing a large auditorium. The deteriorating structure, too costly to repair, was not needed and its salvaged pieces were used for a small picnic shelter. However, the remaining portion of the YMCA building was ideal for rehabilitation into a five-room quarters for a caretaker. Concrete latrine bases were broken up and removed along with lead packing, iron piping, and wood scraps. [23]

In 1927, reformatory workers from the Chillicothe Correctional Institute planted and harvested an oat crop on the mounds before cultivating a mixture of timothy and blue grass.

|

| Figure 17: Mound City Group restoration of the mid-1920s, looking northwest. Note Death Mask Mound at left with stairway and viewing platform. (Ross County Historical Society, ca. 1927) |

|

| Figure 18: Mound City Group restoration of the mid-1920s, looking southwest. Taken from atop the observation platform, note the perimeter earthwall, restored mounds, and sterile landscape. (NPS/ca. 1927) |

Workers finished rehabilitating the caretaker's home, converted a latrine into a tool house, and painted both buildings. With the fencing of the monument, Spetnagel reported confidently that the area would soon be ready to open for visitors. [24]

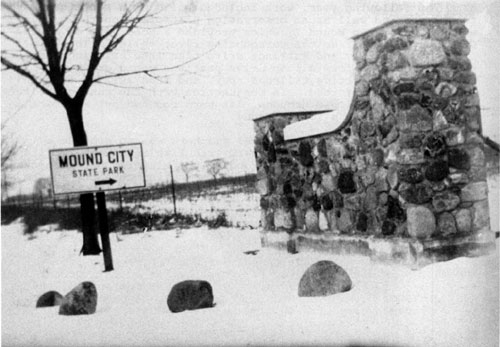

The following year, work included building a stone gateway to the park as well as an observation platform atop the high, centrally-located Mound 7, which provided a good view of Mound City Group as well as the surrounding river valley. The ornamental gateway and entrance drive tied into existing Camp Sherman roads to form a loop drive past the mound group, paralleling the active railroad spur, and then exiting through the north boundary road. In conjunction with the rustic shelter and surrounding picnic grounds, laborers roughed out a baseball diamond for use by a local league.

Clearly, the intent of local planners was to provide a recreational emphasis for the park with little concern for its true national significance. Proud of the gleaming new picnicking grounds, Chillicothe staged its own dedication ceremony in the early summer of 1929 as the new state park opened for visitors. The local newspaper revealed future plans of the Spetnagel group for "winding roadways with extensive parking facilities, the planting of a variety of shade trees and the laying out of picnic grounds to the east and bordering on the river." [25]

Funding for such development was not forthcoming from Columbus, nor would it be as financial crisis on Wall Street in the early fall of 1929 precipitated a virtual collapse of the nation's once-booming economy. As the Great Depression gripped the country, budgets for Ohio parks flattened and declined.

|

| Figure 19: Newly-constructed entrance gate and sign for "Mound City State Park." (Collection of the Ross County Historical Society/1928) |

Growing public complaints about the lack of facilities development brought a subcommittee of the state finance committee on an April 1933 visit. After an inspection tour in which legislators called Mound City "the best kept and cleanest state park they had seen anywhere in Ohio," local representatives asked for shelter houses to be considered as soon as possible for park development. As their predecessors had done in previous years, the legislators promised to advocate increased development only in accordance with the state's worsening financial condition. [26]

Even as the spring 1933 visit took place, steps were being taken in Washington, D.C., to change the course of historic preservation in the United States. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt followed through on a plan by his predecessor to reorganize the executive branch via executive order. One bureau that benefitted tremendously was the National Park Service which became charged with administering all of the national monuments scattered throughout federal departments. For example, in addition to historical battlefields, the War Department relinquished control of its national monuments, including Mound City Group, effective August 10, 1933. The move consolidated the function of federal historic preservation into one agency: the National Park Service. [27]

Six weeks prior to his inauguration as the thirty-second president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed to employ a quarter-million men in public works and conservation projects as a means of breaking the cycle of social and economic misery brought about by the Great Depression. A compliant Congress, alarmed by the mounting despair and panic pervading the American public, gave the new president a virtual carte blanche and authorized much of Roosevelt's "New Deal" proposals. Thus began the United States' turn away from laissez-faire capitalism to an active course of federal intervention and regulation in not only the economy, but many other areas of American life.

During the "First 100 Days," Congress passed and Roosevelt began implementing his strategy to provide immediate relief. In March 1933, President Roosevelt officially announced the formation of Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) which soon became popularly known as the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Four departments of the executive branch had authority over the New Deal program: Labor to select the enrollees; War to handle administrative concerns; and Agriculture and Interior to utilize the manpower. Of these last two departments, two bureaus reaped the most benefit from this unemployment relief program: Agriculture's U.S. Forest Service and Interior's National Park Service.

For the National Park Service (NPS), ECW/CCC meant the opportunity not only to develop the long-neglected national parks, but to provide a needed boost to the nation's individual state park systems. Initially, Assistant Director Conrad Wirth turned to the Washington Office's division of Planning and State Cooperation to handle the new program. The project's magnitude prompted the bureau to decentralize its operations in August 1937 by establishing four NPS regional offices in the following cities: Richmond, Virginia (Region I); Omaha, Nebraska (Region II); Santa Fe, New Mexico (Region III); and San Francisco, California (Region IV). The regional offices directly supervised NPS field personnel and equipment; oversaw funding; approved designs; and supplied technical expertise. Areas within each NPS region were further subdivided into district offices containing field inspectors who, in addition to certifying projects, gave advice on designs and plans. Ohio, which fell under the purview of the Region I Office in Richmond, was served by the District D Office in Cincinnati, and later by the CCC Ohio Central Design Office in Columbus. [28]

Because Mound City Group National Monument hung in limbo until its late summer transfer to NPS jurisdiction, it did not benefit directly from CCC labor or NPS oversight. Chillicothe and south central Ohio, suffering from high unemployment and depressed agricultural prices, needed immediate help and the undeveloped Mound City Group provided an ideal place to stage emergency public works projects. Therefore, the mounds received similar conservation assistance as a result of two other New Deal emergency relief programs: Civil Works Administration (CWA) and Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA). CWA/FERA combined funding in 1933 and 1934 to construct two buildings. The first was a massive two-story with partial basement frame utility/maintenance garage building with toilet facilities and a coal furnace. Its rough sawn redwood timbers were salvaged from a nearby covered bridge. Because temporary quarters for the caretaker were placed on the second floor, most likely the deteriorated Camp Sherman-era YMCA building was razed at this time. The second was a one-story, two-room masonry comfort station with wood shingle roof measuring more than 430 square feet. Unheated, the building featured concrete facilities with open-pit toilets and unfinished interior walls, floors, and ceilings. [29] The rustic architecture of the facilities mirrored similar park construction by the National Park Service-directed Civilian Conservation Corps.

|

| Figure 20: Mound City Group custodian's residence and maintenance building. (NPS/early 1940s) |

|

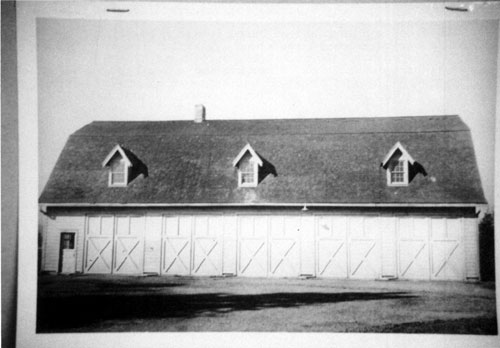

| Figure 21: Imposing maintenance building, the second story later featured dormer windows to accommodate groundskeeper James Sampson. (NPS/early 1940s) |

Yet another relief program, the Works Progress Administration (WPA), funded two additional park improvements in 1937. First, WPA workers built a one and one-half story wood frame residence on a masonry foundation adjacent to the utility building. The house, also with a coal furnace, featured a total of twenty-seven rooms (including closets) and had a ten-by-ten-foot office for park administrative purposes at its east entrance. The house and the utility/maintenance garage building were both stained gray to emulate aged redwood.

The second WPA building was a one-story, two-room picnic shelter house measuring more than 2,640 square feet. A rustic chestnut frame rested on a masonry foundation with stone wall columns connected to a shingle roof. A six-foot cobblestone walk connected to the east side of the shelter and on the west and south sides where an enclosed kitchenette stood. [30]

State workers added soil to many of the mounds, most without consulting the 1848 Squier and Davis documentation. A parking area, walkways, and boatlanding were also installed. Acting on a recommendation from the Division of State Memorials, the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society added Seip Mound, another Ross County Hopewellian earthworks, to Mound City's administration. [31]

By the late 1930s, Mound City Group National Monument had become a full-fledged member of the Ohio state memorial system. Its national nomenclature was largely ignored; state promotional materials referred to it as "Mound City State Memorial," while road signs declared "Mound City State Park," one of about thirty-five such units operated by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. There was no signage announcing its national status to visitors. [32]

Indeed, even the National Park Service remained unconcerned about Mound City Group National Monument. Since Mound City Group's transfer from the War to Interior Department in 1933, NPS officials suggested to their Ohio counterparts that they supported a federal to state transfer of title, but progress on this initiative cooled when Ohio Congressman W. E. Brahn protested the move. However, when Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes approved the transfer on March 6, 1937, NPS Assistant Director Conrad L. Wirth formally announced the proposed move on March 10. [33] In the meantime, NPS perfunctorily pursued a boundary expansion for a wider buffer strip varying from three hundred to six hundred feet along the northern edge of the mounds. [34]

As a quasi-state institution founded in 1885 with support from private members, the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society's budget was subject to the legislature's whim. Within the Division of State Memorials, Mound City fared well budget-wise, but the state's "drastic economy program" made it impossible to plan for sustained growth and development. The society benefitted tremendously from CCC funding and labor at many of its units. As late as 1940, Mound City received grounds maintenance attention from a U.S. Soil Conservation Service camp in Chillicothe. Without the additional federal help, the Ohio sites would not have fared as well as they did through the Depression. Indeed, all of Mound City's capital developments came as a result of federal funding. Curator of State Memorials Erwin C. Zepp acknowledged his dilemma to society members in his 1940 report:

|

| Figure 22: Picnic shelter house built at Mound City State Park. (NPS/June 26, 1937) |

|

| Figure 23: Chillicotheans and Ross County residents soon made the Mound City shelter house their premier recreation destination point. (NPS/June 26, 1937) |

To expand properties and facilities at the expense of maintenance and control is recognized by the Division as unsound policy. With a state policy of economy in force, a program of maintenance and control was mandatory. However, there existed and continues to exist an acute need for expanding the educational phase of the memorial program. To merely preserve historic sites and structures is falling short of fulfilling the mission of the Division of State Memorials. This was increasingly apparent in 1940. The average visitor is becoming more aware and appreciative of his democratic heritage in the light of events abroad. He is seeking to rediscover the facts of Americanism. He is demanding an explanation and an interpretation of the history which is preserved in State Memorials. Museums, guides, literature, signs, and other informative and educational media are badly needed. [35]

Zepp's statement was unquestionably targeted at Mound City Group and its local promoters. The lack of adequate state financing clearly frustrated Mound City boosters in Ross County. Led by Albert C. Spetnagel, the group opposed ongoing negotiations by NPS to relinquish title to Ohio, thereby terminating Mound City Group's national monument status. Such a move, Spetnagel believed, would forever banish the mounds to an inferior position within the state bureaucracy with little development likely to occur anytime soon. Society Director Mills, however, concurred with NPS Historian Herbert Kahler's suggestion that because Ohio funds maintained Mound City since 1923, Ohio should rightfully hold title to it. Mills believed that such a move would eliminate the legislature's reluctance to increase the park's appropriations. [36]

|

| Figure 24: A picnic sponsored by the YMCA brought a large crowd, some of whom toured the prehistoric mound area. (NPS/June 26, 1937) |

|

| Figure 25: With the B & O railroad spur in the foreground, the parking lot for the popular shelter house can be seen beyond the Mound City Group enclosure earthwall. (NPS/no date) |

A summary of Ohio's fiscal expenditures at Mound City Group from 1920 to 1946 is as follows:

| 1920 | $500. | archeological fieldwork |

| 1921 | $499.06 | archeological fieldwork |

| 1922-24 | $0. | |

| 1925 | $2,000. | site work funds spent $683.39 |

| 1926 | $2,000. | site work funds spent $1,216.61 |

| 1927 | restoration $.14; fence $411.18 | |

| 1928 | no data/no annual meeting or report | |

| 1929 | $720. | salaries spent $720 |

| $1,000. | repairs spent $998.15 | |

| $40. | communication spent $1.75 | |

| $2,000. | general plant spent $1,652.80 | |

| 1930 | $2,500. | salaries $510; wages $193.45; agric. supplies $717.25; office supplies $1.00; printing $14.50; building repairs $509.18; and materials $528.78 = $2474.16 |

| 1931 | total disbursements $3,040.65 | |

| 1932 | total $2,948.43 (personnel $1,632.40; maintenance $1,316.03 | |

| 1933 | total $2,152.25 | |

| 1934 | total $2,166.86 | |

| 1935 | total $2,367.76 | |

| 1936 | $2,194.54 | |

| 1937 | $2,500 | |

| 1938 | $3,633.42 | |

| 1939 | $3,228.48 | |

| 1940 | $3,674.96 | |

| 1941 | $3,822.50 | |

| 1942 | $6,423.27 | |

| 1943 | $4,604.62 (became headquarters of District One) | |

| 1944 | $4,463.20 | |

| 1945 | $5,214.36 | |

| 1946 | Park returned to NPS in summer; Curator of Archeology withdraws exhibits. [37] |

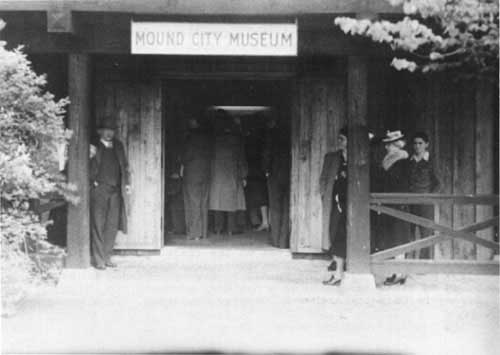

As another world war loomed and the chances of further park development vanished, Spetnagel acted. Ever more cognizant as each year passed that no educational facilities interpreting Mound City Group's significance to the public would be forthcoming from Columbus, he donated funds to construct a small museum. Spetnagel paid more than $780 to remodel the kitchenette at the end of the shelterhouse into a display room, with the south walkway also enclosed at the same time. He also donated a display case within which he placed Hopewellian artifacts from his personal collection. A small spotlight lit the display area. The Mound City museum opened with a special dedication ceremony on May 26, 1942. [38]

Albert Spetnagel's intentions, however, were not respected or followed by the Columbus society. The only Mound City Group-related interpretation provided to the public were Spetnagel's own donated artifacts. The society's interpretive displays said nothing about Mound City Group. On the walls were a large map of Ross County, artifacts and photographs related to the three cultures of Ohio's mound builders, and similar depictions of artifacts relating to Ohio's other archeological sites. Locals noted that after the museum dedication, Albert Spetnagel withdrew from his active participation in the society. Local opposition to the proposed transfer of Mound City Group National Monument to the state had his full support. [39]

National and world events in the late 1930s and early 1940s prevented substantive progress on the transfer. Mound City Group never became a priority for action. As early as December 20, 1940, NPS Chief Historian Ronald F. Lee recommended Mound City Group be dis-established as a national monument, to which Associate Director Arthur B. Demaray concurred. In a background check on the issue, one official wrote to Assistant Director Conrad Wirth:

|

| Figure 26: Thanks to Albert C. Spetnagel, the shelter house's kitchen became the "Mound City Museum." (Collections of the Ross County Historical Society/1942) |

...it is a very important site, but... was pot hunted by early students, Squier and Davis, in 1846, and later 1920-21 was systematically dug out by the Society. So there is little left in original condition. The historians say that it is representative only of the culture, a very important one of the Hopewell people, but it has been so disturbed and restored that little original condition remains. They want another, untouched, example of what the Hopewell people left behind and say that it might be possible to obtain one for the NPS. [40]

Operations of the national headquarters of the National Park Service were severely impacted when the wartime emergency necessitated drastic personnel reductions and removal of the non-defense agency to Chicago for the duration of the war. Many park units were simply mothballed until after the war. The policy question concerning Mound City Group nonetheless arose again in late 1944, and the NPS chief of interpretation offered a similar recommendation to relinquish title to Ohio. [41]

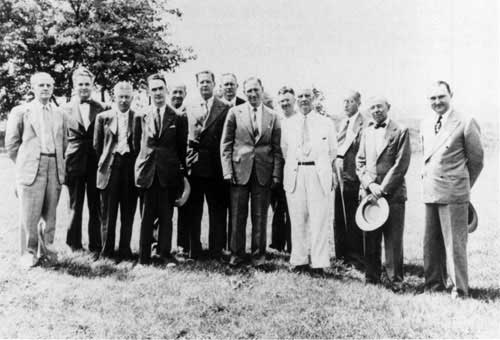

With the war in Europe over and Japan on the brink of defeat, steps were initiated in May 1945 to achieve the transfer. Upon approval of Ohio Governor Frank J. Lausche, the National Park Service prepared draft legislation to effect the deed transfer. When news of the effort reached Chillicothe, four powerful groups formed a coalition to voice their opposition. The coalition, whose membership included the Chillicothe Chamber of Commerce; Chillicothe Retail Merchants Association; Chillicothe Newspapers, Incorporated; and Ross County Historical Society, for the first time publicly announced dissatisfaction with Mound City Group National Monument's management by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. It called for revocation of the 1923 War Department license and advocated National Park Service assumption of daily site management. The coalition formed a special committee, called the "Mound City Committee," to achieve its goals. Its membership included the following prominent businessmen: J. Herbert Mattox, Roy Drury, Nelson L. Kellenberger, Eugene D. Rigney, Oliver O. Overly, Earl Barnhart, David McKell, David Crouse, J. K. Hunter, and Harold Cruit. [42]

|

| Figure 27: The Mound City Committee, a coalition of local businessmen, mobilized to transfer Mound City Group National Monument from state to federal stewardship. (Chillicothe Gazette, August 21, 1945) |

Along with wide press coverage of their action, the Mound City Committee's most effective move came with a lengthy letter to Eleventh District Congressman Walter E. Brehm outlining the "deplorable condition" of Mound City Group National Monument along with recommendations on how to remedy it. The committee's well-argued grievance against the society included the following statement:

In twenty-two years, The Ohio State Archaeological & Historical Society has done nothing to improve or develop the property; to the contrary, it has permitted a National Monument to become little more than a roadside park. During the course of exploration of Mound City by the State Society, in 1920-1921, a magnificent collection of prehistoric art was discovered and promptly hauled off to Columbus where it has remained, partly in storage, despite the fact that it is federal property and should have been displayed in a museum on the site. The State Society has never instituted a program of interpretation, although this was suggested years ago by the National Park Service.

The State Society has always ignored the area's status as a National Monument and has classed it as another of the State Memorials under its supervision. As such, picnic facilities were provided and landscaping carried out. No attempt was made to provide a museum on the site or in any other way to foster knowledge of the area. Neither printed guides nor even the simplest form of descriptive leaflet have ever been available for general distribution in, or about, the area. There are no signs at the entrance indicating Mound City IS a National Monument. The only descriptive plaque in the area (besides one prohibiting the use of 3.2 beer!) recites the number of mounds, and suggests that the visitor (who reasonably expects to learn about Mound City on the site) may travel fifty miles farther to Columbus for the privilege of seeing the artifacts removed from the mounds! It is little wonder, then, that visitors have skirted the mounds on their way to picnic spots and departed without the faintest conception of the importance of their surroundings. [43]

The letter mirrored Albert Spetnagel's long-standing disgust at the society's inaction and his personal funding of the existing inadequate museum. The society refused to place its Mound City Group artifacts there because the facility was not fireproof. The group opposing the transfer to Ohio called it "a little room with a complex, unimportant mass of material from other mound areas, to pad out a meager showing of trifling odds and ends, plaster casts and some photographs of pieces from Mound City. The visitor is still bewildered." [44] The committee further informed the congressman that the monument's budget was inadequate, resulting in deteriorated roads and "antiquated facilities" as the hallmarks of the society's "slipshod operation."

The coalition demanded revoking the society's operating license and placing Mound City Group National Monument under National Park Service management. Once accomplished, NPS should:

fully develop the area and erect a suitable, fireproof museum building to house the superb collection of prehistoric art, owned by the federal government, and, at present, in the Ohio State Museum. The Mound City Museum should be in keeping with the quality of the fine art housed therein and with the dignity of the surrounding area. The size of the building should be governed not only by the collection stored at Columbus but also by the distinct possibility of recovering the Davis Collection of Mound City material (including over two hundred effigy pipes) from the British Museum. [45]

Finally, the group called for the congressman to work for adequate NPS appropriations for monument maintenance and development, as well as a site visit for an NPS architect to conceive cost estimates for site construction. It asked for expeditious action: "We believe that every effort should be made to have all phases of this program instituted or in operation by 1946, the 100th anniversary of the first exploration of the Mound City area by [Squier and] Dr. Davis." [46]

After having been the target of fierce lobbying since May 1945, which included Ohio's U.S. Senators Robert A. Taft and Harold H. Burton, Governor Lausche withdrew his support for the transfer on August 1. Lausche informed Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society Director Henry C. Shetrone,

It is my considered judgment that further negotiations for the transfer of title to this land from the Federal Government to the State Government ought to be promptly terminated. The preponderance of judgment is that it would be better for the development of the memorial and for the attraction of tourists to that community to have title remain in the Federal Government. It is further revealed to me that the Federal Government is not insisting nor asking that the title in the memorial should be taken in the name of the State of Ohio. [47]

Congressmen Brehm acted immediately. On August 21, 1945, Brehm, accompanied by NPS Chief Historian Herbert E. Kahler, met with the committee and local officials and toured Mound City Group. Kahler advised that an appropriations request would have to be submitted by September 15, and at Brehm's request, an NPS architect would be sent to survey the area. [48] In September, Acting NPS Director Hillory A. Tollson requested Region One Director Thomas J. Allen to send an architect to Chillicothe to prepare a master plan. [49] The same month Tollson informed Brehm that an Interior appropriations request for Mound City Group maintenance and operations had been forwarded to the Bureau of the Budget on its way to the House Interior subcommittee. [50] Regional Landscape Architect Ralph W. Emerson arrived for an inspection of Mound City Group's condition and needs in late October 1945. Emerson surveyed the grounds for the proposed museum and any other necessary developments to "bring the park up to federal standards." [51]

NPS officials, forced by public and political pressure to take Mound City Group National Monument seriously after twenty-two years, were never comfortable about the management arrangement with Ohio. Many questioned whether the revocable license was actually legal in the first place. Forced to assess the situation because of the dissatisfaction of Chillicothe citizens, NPS acknowledged the prevailing political winds and honored Governor Lausche and the Ohio congressional delegation's wishes. The federal bureau announced its intention to take charge of Mound City Group National Monument at the start of the next fiscal year: August 1, 1946.

The National Park Service Assumes Control

Although a bitter pill to swallow, officials at the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society bowed to the inevitable. On September 21, 1945, the society's board of trustees passed a formal resolution concurring that Mound City Group National Monument should be returned to the federal government. Further, the board pledged its support to help the Ross County Historical Society achieve the goal. [52] However, the society realized Ross County citizens advocated return of the Mound City Group artifacts gathered in 1920 and 1921, and few on the board supported such a move. Little did board members realize that NPS officials were already investigating the question of who owned that collection, the federal or state government. On September 5, 1945, the Department of the Interior requested a War Department review and report on the matter. The answer came on April 19, 1946, in a letter from Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson:

A search of the records of this Department and a study of files pertinent thereto discloses no grant of authority from the United States to the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society to excavate in the Mound City Group, Camp Sherman, Ohio. A study of the records indicates that the license granted said society on 27 March 1923 was the only license properly granted. This license provided that no excavation of the mounds would be allowed except upon permission granted by the Secretary of War. There is no evidence available that such permission was ever granted. It, therefore, appears that the artifacts excavated by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society in the Mound City Group and removed therefrom were taken without right. Accordingly, it is the opinion of this Department that the subject artifacts remain the property of the United States. [53]

NPS officials determined not to make an issue over its ownership of the 1920-1921 Mound City Group artifact collection. Because there were not adequate curatorial facilities at Mound City Group or in Chillicothe, particularly at the Ross County Historical Society and Museum, NPS officials were no doubt content to maintain the status quo and not antagonize their state counterparts unnecessarily. For the time being, the collection would remain in Columbus.

Notice that the 1923 Mound City Group management license with the War Department would be revoked as of August 1, 1946, came from Interior in early 1946 when it became clear Congress would include Mound City Group in the fiscal 1947 NPS budget. The revocation notice came in a letter to society director Henry C. Shetrone. Interior recognized the society's role in saving Mound City Group from destruction, and guiding its development program. [54]

Regional Archeologist J. C. Harrington arrived at Mound City Group on July 30, 1946, to make last-minute arrangements for the transfer. William W. Luckett accompanied Harrington from Richmond to Chillicothe. Luckett, who served as custodian at Shiloh National Military Park (Tennessee), Ocmulgee National Monument (Georgia) and Salem Maritime National Historic Site (Massachusetts), entered on duty as acting custodian of Mound City Group on his way to his next permanent assignment at Fort Pulaski National Monument (Georgia).

On the morning of August 1, Harrington accepted responsibility for the park from Richard S. Fatig, curator of state memorials for the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society. Harrington reported the park to be in good physical condition, "mowed and every part of it was neat and clean." However, the temporary museum was stripped bare. The society had withdrawn its exhibits, as had Albert C. Spetnagel, who probably did so to spur federal park officials into approving long hoped for developments. The society also removed its equipment and signage from the Chillicothe park.

With the agency's position on retaining Mound City Group National Monument within its system of federal parks remaining unclear, the National Park Service faced the daunting task of "starting from scratch." [55]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hocu/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 04-Dec-2000