|

Hopewell Culture

Amidst Ancient Monuments The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio |

|

CHAPTER FOUR

Administering the Mound City Group

It takes good managers and a talented, hard-working professional staff to make park administration and operations a success. Mound City Group National Monument and it successor entity, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, have largely enjoyed both. With a dedicated corps of park professionals in Chillicothe, the park's geographical positioning near the center of the state, close to the capital at Columbus, made it a natural focal point for National Park Service operations in Ohio. In the early 1970s, Mound City Group National Monument, itself already fully developed, served as headquarters for the "Ohio National Park Service Group," whereby all Ohio's federal parks answered to the "general superintendent" in Chillicothe and Mound City Group staff served more than one park. Known within the bureau simply as the "Ohio Group," the cooperative administrative entity endured only a few years.

The idea refused to die, however, as Mound City Group/ Hopewell Culture employees helped establish and augment operations as new federal park units came on-line in Cincinnati, Cleveland/Akron, and Dayton. Bureau reorganization in the mid-1990s created new opportunities for the Chillicothe park to shine within the National Park Service's Midwest Region and presented a real possibility of cooperation among Ohio's federal parks.

National Park Service Staff

Following the March 1962 transfer of Clyde B. King, John C. W. ("Bill") Riddle arrived on September 7, 1962, to become Mound City Group's second superintendent. This represented Bill Riddle's first superintendency, having served as district ranger at Acadia National Park, Maine, with previous assignments at Gettysburg National Military Park, Pennsylvania; and Colonial National Historical Park, Virginia. A management inspection conducted by Northeast Regional Administrative Officer John J. Bachensky found Mound City Group operations "very compact, direct, and efficient" and the four permanent staff in conformance with the Group 'A' category, a designation indicating the monument functioned at a basic operations level with minimal staff. Bachensky foresaw no further increases for permanent or temporary personnel. The staff included Superintendent Riddle, Administrative Aide (vacant), Maintenanceman J. Vernon Acton, and Archeologist Richard Faust. Three seasonal positions included a laborer, information-receptionist, and ranger-historian. [1]

Riddle held the first staff meeting in Mound City Group history on November 26, 1962. The exercise received such high praise that Riddle resolved to hold regular meetings at least twice per month. Riddle hardly had time to adjust to his new position for by mid-June 1965, he transferred to the superintendency of Hopewell Village National Historic Site, Pennsylvania. [2] Administrative Aide Delmar G. Peterson became acting superintendent until James W. Coleman, Jr., entered on duty on July 19, 1965. Coleman, a second-generation Park Service employee, formerly served as historian at Manassas National Battlefield Park, Virginia. [3]

As a newly-developed park with daily operations static and routine, the Mound City Group superintendency ideally lent itself as a training position for new managers preparing themselves for more challenging positions elsewhere. Like his immediate predecessor, Coleman remained at Mound City Group for only two years. On July 2, 1967, Coleman transferred to Saratoga National Historical Park, New York. Coleman's replacement, George F. Schesventer, the former management assistant at George Washington Birthplace National Monument, Virginia, took over the job on July 30, 1967. It was under Schesventer's superintendency that NPS Director George B. Hartzog, Jr.'s, policy of having "state coordinators" became implemented. The politically astute Hartzog ordered one NPS superintendent per state be designated as the bureau's "eyes, ears, and mouth." The coordinator position was a key link between state and federal park and historic preservation programs, and Hartzog intended it to give NPS an elevated profile in state and local political circles. Chillicothe, in close proximity to Columbus, made Mound City Group's superintendent the logical choice to be state coordinator. [4]

|

| Figure 37: Mound City Group National Monument staff: (left to right) Kathleen Allyn, Virginia Skaggs, Walter Fraley, Linda Shreve, Nicholas Veloz, Susan Brady, J. Vernon Acton, and George Schesventer. (NPS/Phillip Egan, June 10, 1969) |

In addition to his liaison role, Schesventer also assumed superintendent responsibilities for William Howard Taft National Historic Site in Cincinnati upon its authorization by Congress on December 2, 1969. Schesventer continued in that capacity until December 3, 1970. The following day, at the behest of Director George Hartzog, the Ohio National Park Service Group was established with headquarters at Mound City Group National Monument. Taft, along with Perry's Victory and International Peace Memorial, were linked with Mound City Group and administered by the Office of the General Superintendent physically located at Mound City Group. Schesventer was not designated general superintendent of the new entity, however, as he transferred on March 6, 1971, to assume the superintendency of Castillo de San Marcos and Fort Matanzas National Monuments, Florida.

Taking his place in Chillicothe and filling the new Ohio NPS Group general superintendency, William C. ("Bill") Birdsell began his duties on March 7, 1971. [5] Public relations was at the heart of Birdsell's position as he acknowledged in early 1974: "It became apparent shortly after the Office of the General Superintendent was established that NPS public relations in the State of Ohio were in need of top priority attention. It was of major concern to us," Birdsell wrote, "that U.S. Representatives and Senators and the Governor and his staff were not even aware of National Park Service areas in their state, and that most local townspeople had never visited their neighboring NPS sites." [6]

Tying Park Service units together to achieve economy and coordination in operations had long been a favored practice. Grouping all NPS units within a state under one general superintendent represented something tried in several other areas, but largely discarded after the 1970s, particularly after President Richard M. Nixon's December 1972 firing of NPS Director Hartzog. [7] Remarkably, Bill Birdsell had not previously been a superintendent before he received his new assignment with Hartzog's blessing. [8]

|

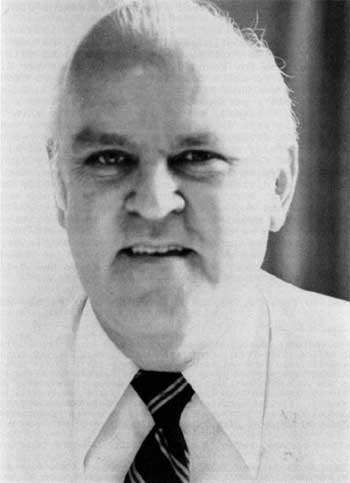

| Figure 38: Superintendent William C. ("Bill") Birdsell. (NPS/Betty White, May 1974) |

Although Birdsell continued to lobby for it, he was unsuccessful in getting Northeast Region approval to fill the park manager position for Mound City Group in order for Birdsell to devote full-time to state coordinator and Ohio NPS Group duties. [9] In fact, the Ohio NPS Group existed only through the strength of Birdsell's personality. It never received a separate budget allocation. Instead, Birdsell was forced to skim funding from all three Ohio park units, but with extra amounts taken from William Howard Taft National Historic Site which had yet to be restored and made fully operational. Birdsell staffed his office with Administrative Technician Joan Crider, Secretary Virginia Skaggs, and Clerk-Typist Rhonda Hughes. George Kane, the only NPS ranger in Ohio, divided his time between Mound City Group and the visitor season at Perry's Victory. Ohio NPS Group employees Birdsell, Skaggs, and Hughes took care of administrative and clerical matters for Mound City Group, with interpretation and maintenance remaining as the only full-time permanent function allotted for Mound City Group. Park Technician Bonnie Meyer took care of visitor services and interpretation for four summer seasons at Perry's Victory before transferring to Mound City Group in winter 1973-74 to fill a permanent position. [10]

On January 6, 1974, following establishment of the Rocky Mountain Region, NPS underwent a fundamental shift of boundaries. The Ohio parks, already subjected to two previous regional realignments (Region One/Richmond and Region Five/ Northeast Region, Philadelphia), found themselves shifted yet a third time to the purview of Midwest Regional Office with headquarters in Omaha, Nebraska. Effective March 1, 1974, the administrative transfer took place and Ohio NPS Group began reporting to Midwest Regional Director J. Leonard Volz. [11] While the Northeast Region directorate favored "grouping" parks, officials in Omaha did not. Termination of the Ohio NPS Group became imminent. Upon authorization of Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area on June 26, 1975, Bill Birdsell, who as state coordinator had served as project keyman for the proposed unit sandwiched between Cleveland and Akron, Ohio, became the new park's superintendent. Effective July 1, 1975, the Ohio Group dissolved. All four Ohio parks became autonomous with their superintendents reporting to Omaha. When Birdsell left Chillicothe on July 21, he took his state coordinator duties with him. [12]

That was not all Birdsell took with him. In addition to using Mound City Group personnel to perform maintenance and administrative tasks prior to hiring his own staff, Birdsell took Mound City Group capitalized equipment, including a vehicle, and other materials to Cuyahoga Valley. When Fred J. Fagergren arrived in Chillicothe to replace Birdsell on October 26, 1975, he found the unauthorized transfer of property intolerable. Fagergren complained to Regional Director Volz that not only would he have to debit his own budget to replace the items, he resented the fact that Cuyahoga Valley, as a new area, would henceforth automatically receive priority funding at levels higher than Mound City Group's. [13]

|

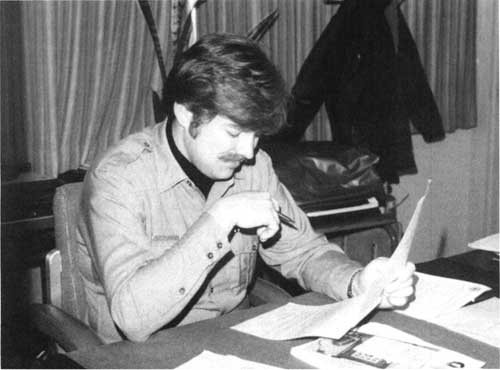

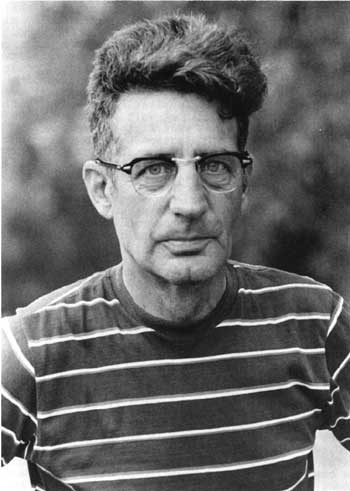

| Figure 39: Superintendent Fred Fagergren, Jr. (NPS/Theresa Nichols, January 1979) |

An operations evaluation report in February 1976 conducted by Midwest Region personnel concurred with Fagergren and recommended expedited replacement of the "fairly significant list of property and supplies" removed from Mound City Group. In examining the de-clustering of the Ohio parks, the team reported it "has had [a] less positive effect on Mound City than on the other units." Grade-level re-evaluations were recommended for the superintendent, administrative technician, and secretary, and the team urged speedy review and approval of a new park organizational chart. [14]

Superintendent Fagergren's tenure at Mound City Group spanned five years. Like Coleman, Fagergren was a second-generation Park Service employee. Mound City Group represented his first park management assignment, and Fagergren was its first superintendent with a degree in anthropology. Fagergren's administration embodied a significant time of transition when studies on other Hopewell sites were prepared that subsequently spawned an initiative to expand and transform Mound City Group. Fagergren aggressively pushed for change with a determination to reorient the park's interpretive focus upon its cultural resources. [15]

Upon Fagergren's transfer on March 7, 1981, Ken Apschnikat became Mound City Group's seventh superintendent on April 19, 1981. Apschnikat, historian at Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, naturalist at Shenandoah National Park, and chief of interpretation and visitor services at Richmond National Battlefield Park, all in Virginia, had eleven years of experience before assuming his first park management post. [16] Apschnikat's tenure arrived at the same time the administration of President Ronald W. Reagan began implementing its tight controls on land-managing federal agencies through Secretary of the Interior James G. Watt. Watt, a conservative Westerner who wanted to curb federal power over the private sector, instituted a moratorium on federal land acquisition until such policies could clearly be spelled out through Interior-approved land acquisition plans. In the meantime, as the nation slipped further into an economic recession, NPS adopted "basic operations" plans for each unit. Mound City Group's focused on resource preservation and protection. Apschnikat's basic operations objectives were as follows:

To identify, inventory, and evaluate the park's cultural resources; to monitor their condition; and to preserve, protect, and interpret them in a manner consistent with the requirements of the enabling legislation, historic preservation laws, and National Park Service policies.

To ensure, through authorized acquisition or other means, a land base that is adequate to protect and interpret the burial mounds and associated cultural resources.

To help ensure that land use and development in the park's vicinity are compatible with long-term preservation of park resources through cooperation with other agencies, organizations, and interests.

To protect the historic and prehistoric resources from erosion by the Scioto River.

To foster public understanding and appreciation of the Hopewell and other native American cultures and the relationship between these people and their environment, as well as the more general evolution of the relationship between man and his environment.

To re-establish to the degree possible, the historic scene to reflect the environment of the "Hopewell Culture." [17]

Watt came into office believing the national park system had grown too big, too fast, and contained units of less-than-national significance which should more properly be administered by state or local governments, non-profit organizations, or other qualified groups. Reminiscent of the 1950s, when Interior's inspector general began making plans to audit such small historical parks, Mound City Group National Monument once again found itself on a deaccession "hit list." The uproar from around the country, spearheaded by cultural and environmental interest groups, was angry and immediate. Stunned by the response, Secretary Watt publicly disavowed knowledge of the move, instructed that the audits be cancelled, and stated no part of the national park system would be dismantled while he held office. [18]

|

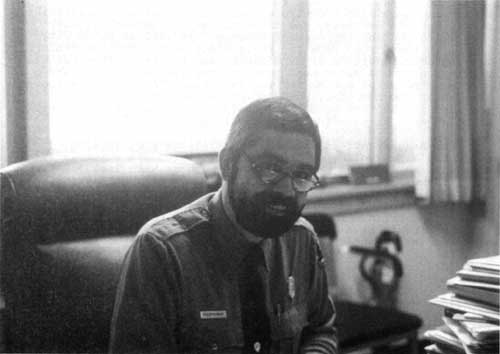

| Figure 40: Superintendent Kenneth Apschnikat. (NPS/November 1982) |

The Reagan administration launched a number of federal spending programs in the early 1980s to ease the brunt of a deepening domestic economic recession. For NPS, still under tight land acquisition controls, Watt wished to improve existing parks, not add new ones, and launched the billion-dollar Park Rehabilitation and Improvement Program. In 1982 at Mound City Group, it meant road repairs, replacement of the visitor center viewing deck, addition of handicapped and bus/recreation vehicle parking, a ground water heat pump for the visitor center, and a solar-heated water system for the residence. Additional manpower came under the Emergency Jobs Appropriation Act of 1983. It provided $28,500 for Mound City Group to replace the river trail steps as well as painting and general repair work. [19]

The Reagan/Watt-imposed basic operations program also generated a new policy of "management efficiency," which in effect formalized the practice of "doing more with less." Managers were encouraged to identify a range of cost-saving measures. A part of this exercise involved the Office of Management and Budget's "Circular A-76," which entailed contracting various federal functions to the private sector. A primary target for A-76 was grounds maintenance and janitorial services (see Chapter Seven). A-76 symbolized the administration's anti-big government stance that many federally-performed activities could best be handled by private enterprise. At Mound City Group in 1983, as at most parks, A-76 was deferred pending further instructions, and eventually the bureau received an exemption from Congress. [20] To improve productivity, the park installed a radio system, a pay-telephone for visitors, converted the secretary from subject to furlough to full-time permanent, and purchased its first computer, a Xerox 820-II to streamline administrative functions. [21]

Seeking to improve efficiency further, the park purchased its own touch tone telephone system in 1984, which resulted in reduced service costs, increased staff efficiency, and shorter time periods in placing calls. Mound City Group had come a long way since its last upgrade in service. In 1962, it switched from an eight-party business line to two private lines, one each in the visitor center and residence. Unsatisfactory service from the Federal Telecommunications System (FTS) operator in Columbus, led to going through Cincinnati at a higher cost. Prohibitively high costs to install its own FTS line or accessing FTS through the Veterans Hospital continued to frustrate Mound City Group managers. [22] An evaluation of how electronic transmission of data between the park and Midwest Regional Office via computer and telephonic modem began in 1985, and succeeded in April 1987 when timecards, payroll data, and reports could easily be exchanged. [23]

William Penn Mott, Jr., only the second NPS director to visit Mound City Group National Monument, arrived on November 24, 1985, for a brief park tour and side trip to Hopeton Earthworks. [24] Superintendent Apschnikat, attempting to implement provisions of Mott's "Twelve-Point Plan," began working with a local American Indian citizen to form a park friends group. The effort did not bear fruit. [25]

Despite the perceived heavy-handedness at the top executive branch level, Superintendent Apschnikat continued to make positive changes. On August 25, 1986, Ken Apschnikat issued the first compendium of "Superintendent's Orders" for the monument. He set visiting hours to daylight periods only, except for special evening programs or by individual permits. To prevent erosion, mounds and earthwalls were closed to public foot and vehicular travel, although visitors could walk between these features. Recreational pursuits such as jogging, kite-flying, and games were confined to the mowed turf area between the highway and visitor center, principally to "reduce potential for accidents with other visitors, to avoid disturbing those visitors taking part in activities deemed appropriate to management objectives of the area, and to preserve the dignity of the prehistoric burial area." Gathering or collecting of fruits, nuts, berries, mussel shells, leaves, and other natural resources were also prohibited. To protect government property and for fire prevention, lighting or maintaining fires, and the use of stoves or any other cooking device, were banned as well. [26]

To offset flat budgets, a donation box first appeared in the museum area near the visitor register and free brochure rack in November 1985. The following calendar year donations nearly totalled $2,600. Donated funds were used to support ongoing park projects. In 1987, Congress first instituted park entrance fees at 135 areas, and $54 million was earmarked nationwide for research and visitor services with the remainder of NPS fees going back into the U.S. Treasury. Mound City Group used its portion of fee money to hire seasonal employees for curatorial work ranging from inventory to preparing exhibits to research, and seasonal rangers for walks and talks on summer weekends. On July 1, 1988, the monument began charging an entrance fee in the visitor center. Donation box contributions immediately declined. Remarkably, only a few visitor complaints were received, most of which came from locals who frequented the park. [27] The one-dollar per person fee or three dollars maximum per private vehicle charge netted the park fifty percent of the revenue, plus an additional percentage of total nationwide fees based on the monument's budget. [28]

Doubling of the single visit entrance fee in 1993 resulted in an eighteen percent drop in visitation from the previous year. Instead of the one-dollar charge, the fee went to two dollars, and the vehicle entrance fee went from three to four dollars. Total revenues from entrance fees surpassed $13,500 for 1993. [29]

Lack of sufficient administrative office space had been an issue since the visitor center's opening in 1961. Innovative ways were found to jam together a growing number of employees, office equipment, and files into a small space. A 1987 operations evaluation report, acknowledging the difficulty in securing funding for a visitor center expansion, recommended adapting the quarters for administrative offices and storage. Upon Ken Apschnikat's transfer on August 13, 1988, work began that fall and winter on the superintendent's residence to convert it to a new administrative headquarters. Offices were fabricated for the superintendent, administrative technician, secretary, chief of interpretation and resource management, and maintenance worker foreman. Space for a lunch/break room, copier/mailroom, conference and storage rooms were accommodated. Office space promised to become less problematic in the late 1990s when a new maintenance building allowed conversion of the previous structure into the "Resource Management Building." [30]

Administrative Technician Bonnie Murray served in an acting capacity from August 14 until Superintendent William Gibson arrived on December 4, 1988. Gibson, chief ranger from Saratoga National Historical Park, New York, was also in his first park management position. [31] Gibson and staff occupied the new headquarters building in the fall of 1989. In one of his first moves, Gibson ended the twenty-four-hour flag-flying policy at the visitor center, conforming flag protocol to reflect operating hours only. In 1989, computer automation extended to all park divisions as the technology became integral to budget formulation and preparation of reports and correspondence. Reflecting increased responsibilities and an expanding park, position upgrades were approved for the superintendent (GS-11 to GS-12) and park ranger (GS-05 to GS-07) in 1990. On October 6, 7, and 8, employees were furloughed and the park closed because of lack of congressional appropriations. [32]

The first facsimile machine came in October 1990, a gift from the Midwest Regional Office. While enhanced communication with Omaha had been a reality for a number of years, "fax" capacity meant almost instant contact with hard-copy documents. Automation also continued to advance as new equipment arrived and curatorial employees began tracking collection items in a database.

|

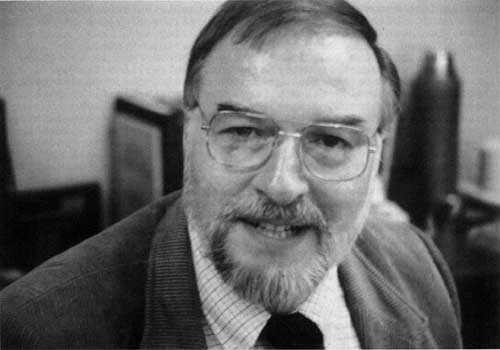

| Figure 41: Superintendent William Gibson. (NPS/February 1991) |

On June 14, 1990, the third NPS director to visit Mound City Group, James Ridenour, toured the park on his way from Washington, D.C., to his Indiana home. [33]

Following up on the groundwork laid by his predecessors, Superintendent Gibson and his staff worked tirelessly to assist NPS efforts to transform the park and other nearby related sites into Hopewell Culture National Historical Park (see Chapter Ten). In spite of the roadblocks to land acquisition erected during the Reagan administration, success finally came when President George Bush signed the authorizing legislation on May 27, 1992.

Much had occurred in the course of Mound City Group National Monument's seven-decade history. The roadside municipal playground of Clyde King's era had steadily progressed under a succession of competent NPS managers to a point where its resources were fully appreciated, preserved, and interpreted in a broader cultural context. In 1992, more than just the "City of the Dead," Mound City Group became the administrative hub of a larger NPS unit including additional sites related to the Hopewell culture.

Lack of funding to implement provisions transforming the area into Hopewell Culture National Historical Park limited transitionary measures during that fiscal year to simplistic, cosmetic changes like new letterhead and signage. Mound City Group's visitor brochure received a wrap-around interpretive flyer explaining Public Law 102-294 to visitors during the interim period. [34]

Superintendent Bill Gibson transferred as the first superintendent of Dayton Aviation National Historical Park in Dayton, Ohio, in April 1993. Administrative Technician Bonnie Murray provided administrative support, earning herself a temporary promotion. Because permanent staff increases for Dayton Aviation Heritage were slow to materialize, Gibson's arrangement with Hopewell Culture continued, eventually leading to Murray's upgrade to administrative officer with plans to hire administrative assistants at both areas. Hopewell Culture received a new superintendent in July 1993 when John Neal, formerly park manager at Missouri's George Washington Carver National Monument, entered on duty. With the nationwide implementation of "Ranger Futures" at mid-decade, Hopewell Culture Chief of Interpretation and Resource Management Robert Burgoon and Park Ranger Robert Petersen both received grade increases, from GS-09 to GS-11, and GS-07 to GS-09 respectively. Audit of the superintendent position resulted in its upgrade from GS-12 to GS-13 in August 1995. [35]

John Neal not only faced the challenge of managing an expanded park, but effectively dealt with a shift of responsibility from the regional office to the parks. The October 1, 1995, National Park Service reorganization saw not only the states of South Dakota, North Dakota, and Arkansas placed into an expanded and redesignated Midwest Field Area, but the division of the former Midwest Region into two geographic clusters of parks, Great Plains and Great Lakes, with the professional staff in Omaha divided similarly into respective system support offices. Management and coordination of each geographic cluster group fell to a cluster management team. For the duration of the 1995-1997 Great Lakes Cluster Management Team (CMT), Hopewell Culture Superintendent John Neal served as chairman. The important position required devoting considerable attention away from daily park operations to matters covering the six-state Great Lakes cluster. As Great Lakes CMT chairman, Neal oversaw and directed project and budget priority-setting for his park cluster. New responsibilities, including delegation of cultural resources compliance from the regional director to park superintendents, further empowered Neal and his peers. These actions highlighted a new management philosophy to shift responsibility to local, front-line managers and enhance cooperation, not competition, among parks.

Upon the October 1, 1997, reorganization back to the former Midwest Region, the Omaha support staff collapsed into a consolidated Midwest Support Office and delineation among geographic clusters blurred but did not vanish. The two CMTs subsequently blended into the Midwest Leadership Council, and Neal's collateral-duty special assignment ended. [36]

The spirit of Park Service cooperation fluorished among the Ohio parks. In the north, Cuyahoga Valley assisted Perry's Victory in numerous administrative ways. In Southern Ohio, on October 23, 1996, superintendents, supervisory personnel, and professional discipline specialists of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, and William Howard Taft National Historic Site convened at Caesar Creek State Park to discuss the feasibility of integrating park operations. Facilitated by a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers employee, the group discussed forming a potential "Southern Ohio Group," formally sanctioning the shared expertise between park areas that Mound City Group initiated years previously. One of the many offshoots of this cooperative spirit involved agreement on utilizing Archeologist Bret Ruby's expertise to oversee archeological compliance requirements at all three parks per section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act. The largest Ohio park unit, Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, extended its fully operational human resources management office to handle Hopewell Culture's personnel recruitment for permanent jobs and classification of existing positions. The larger park also helped ease Hopewell Culture's conversion to a new payroll entry program. [37]

Fiscal year 1996 hosted numerous furloughs of federal employees as President Bill Clinton battled a Republican-dominated Congress over the federal budget. The longest furlough stretched over the course of several weeks, all the while America's federal government ceased to function except for critical positions and services. The National Park Service shutdown its operations. Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, still experiencing its growing pains, reluctantly closed to the public and went into a mothball status. Essential work remained undone, and the small staff, once back to work, struggled to regain the initiative on a growing backlog of projects. [38]

History of Boundary Changes

The first NPS-produced survey map, prepared by Region One Topographical Engineer George Martin, appeared in late 1946. Efforts, which began a decade previously, continued to secure from Chillicothe Veterans Hospital a northern buffer strip measuring three hundred feet wide and fronting on State Route 104 eastward to the river. In April 1948, VA officials arrived to assess the proposal. Even though the ten-and-a-half-acre tract served its farming program and included the hospital's incinerator, VA officials supported the transfer. Citing its scenic protection and ability to ensure full park restoration, Interior pushed for the transfer before the House of Representatives as the veterans committee considered H.R. 5951. The bill easily passed Congress, receiving President Harry S Truman's signature on April 3, 1952. [39]

Enlarging the boundary to include a total monument area of 67.5 acres raised more questions than were answered. A search of Virginia Military District and early Ohio land records showed imprecise methods adopted to mark boundaries. In fact, when Camp Sherman evolved, the excepted State Route 104 became appropriated by the Army, relocated, and not officially defined again. Neither the VA nor Department of Justice's reformatory possessed surveys, even of the earlier transfer to establish the reformatory. King proposed that all parties agree to accept Camp Sherman's road system for boundary configuration purposes, using the centerpoint of north-south roads as boundary demarcations. During agency deliberations however, Director Conrad Wirth proposed to VA that "where the Monument is bounded by a street the boundary shall be a line fifteen feet toward Monument property measured from and parallel to the center line of the street." In other words, NPS would not own or maintain the road. [40]

While the VA officially acknowledged Wirth's proposal and pledged to cooperate at the local level, in practice, nothing happened. In July 1956, Clyde King, irked by the inactivity and jolted by a sudden land transfer between the VA and Department of Justice, borrowed a transit, measured three hundred feet from the center of Portsmouth Road (effectively dismissing Wirth's position), and pounded in iron posts to mark the proposed boundary. A year later, NPS engineer C. S. Waldren arrived to conduct an official survey and monument the boundaries. When the Bureau of Prisons reformatory indicated its satisfaction, the marking work became complete in September 1957. King wryly noted, "For the first time in its 44 year history the area has defined boundaries." [41]

In late 1958, the VA declared additional land surplus to its needs and notified the General Services Administration (GSA) to effect its disposal. The area included land immediately west of Mound City Group across State Route 104. Regional Archeologist John Cotter arrived on February 25, 1959, to conduct a one-day examination of the tract for archeological resources. The VA lent a road grader and operator to test six strips, fifty feet long, eight feet wide, and about eighteen inches deep to reach sterile soil. Cotter's inspection revealed negative signs of aboriginal occupation. He relayed his findings to Regional Director Daniel J. Tobin with the recommendation that a 300- to 500-foot buffer strip be acquired to protect the monument:

If the National Park Service does not acquire this land, the Department of Justice will definitely take it over for agricultural purposes, I was told by local workmen. This has already been indicated to the National Park Service, I believe, by GSA. This would mean that 'trusty' convicts would be working within a few yards of the new visitor center and directly across the highway from the National Park Service land. This would be most undesirable, as the distraction of visitor interest, plus the possibility -- even temptation -- of a break by the reformatory inmates near a lot full of parked and often unlocked cars, should render obvious. [42]

In March 1959, regional planners met with King to discuss the matter and determined that the land had no historical or administrative value. While NPS determined not to seek its acquisition, it did inform GSA of Park Service interest in keeping the area undeveloped and in continued agricultural use. [43]

The Bureau of Prisons announced in September 1966 the closure of its Chillicothe reformatory and ten-year lease to the state commencing December 1, 1966. Governor James Rhodes announced that the cellblock and hospital segment would serve as a psychiatric treatment and care facility for psychotic prisoners while the remainder of the complex would be a medium security prison, all collectively called the Chillicothe Correctional Institution (CCI). [44] Along with the facility transfer, the Department of Justice leased its farmland to CCI, but in early 1969, however, the department announced plans to dispense with the properties altogether. The announcement prompted Superintendent George F. Schesventer to propose an ambitious acquisition program to add almost 186 acres, in effect, trebling the monument's size. The parcels Schesventer proposed in no particular priority order to Regional Director Lemuel A. Garrison were as follows:

Parcel 1: A forty-foot-wide strip along the park's south boundary measured 2.26 acres. From a management standpoint, the existing boundary, determined then to be down the centerline of Portsmouth Road, was undesirable because NPS controlled only half of its own utility road. Schesventer proposed acquiring all of the road, the southern berm, and enough to plant a vegetative screen between the mound complex and the prison. Prison authorities consistently cut back or removed trees and shrubs along the corridor so as to have an unobstructed field of view to shoot at escapees.

Parcel 2: This 45.44-acre tract on the park's northern boundary would follow both State Route 104 and the Scioto to the VA's drainage ditch. Judging from surface finds, archeologists believed it potentially contained a Hopewell occupation site. Its acquisition could also provide sufficient area for reforestation, a more desirable natural scene than its contemporary agricultural use.

Parcel 3: An 18.37-acre tract in front of the prison contained a large circular Hopewellian earthwall. Because the partial circle could still be seen from aerial photographs, it easily could be reconstructed and interpreted from the visitor center.

Parcel 4: This 114-acre parcel stood on the opposite side of State Route 104 across from the park's visitor center. The same 1959 arguments for its acquisition resurfaced in 1969 and became more urgent because it could now pass out of federal ownership and control. Two buildings at the tract's southwest corner could serve park needs. The largest could serve as a maintenance and storage building, while the second, Camp Sherman's library, could be used to interpret one of World War I's largest US Army cantonments. Schesventer proposed relocating picnic grounds to this parcel's northeast corner to satisfy locals.

Parcel 5: The 5.75-acre tract included four contemporary houses within view of the visitor center. Its acquisition would solve the park's chronic employee housing problem. "The superintendent and the permanent staff," according to Schesventer, "would be able to reside nearby but still not be 'under the guns' of the prison and in the migration route of the Veteran's Hospital mental patients. Future recruiting of employees would be improved if there were housing available to them in the area." [45]

Regional Director Lemuel Garrison sent specialists to inspect the proposed additions. John L. Cotter, chief, office of archeology and historic preservation in the Philadelphia Planning and Service Center, [46] and regional maintenance chief Nathan B. Golub largely concurred with Schesventer's proposals. Cotter believed Parcel 2's acquisition was necessary in order to control Scioto River erosion into archeological resources as well as provide for a "living farm-ethno-historical demonstration area." They recommended reducing Parcel 4 to eliminate the large metal maintenance shed and historic library building which lacked considerable original fabric. Instead, a nearby Camp Sherman-era recreational hall and two brick buildings could be adapted to served as a maintenance, interpretive, and administrative complex to tell the combined Hopewell, Ohio and Erie Canal, and World War I story. Further, they believed the superintendent's residence and utility buildings should be removed for safety reasons as the area came under the direct line of fire from the prison's guard towers. [47]

Garrison forwarded the Cotter-Golub findings, which added up to 172 acres, to Associate Director for Management and Programming Edward A. Hummel. Garrison saw considerable environmental and recreational potential for the additions, as well as a management need to prevent adverse development surrounding the park. In addition, he advocated adding a five-acre strip connecting Parcels 3 and 4 along State Route 104. Because of the urgency involved with the acquisitions, he requested scheduling immediately an amendment to the 1966 park master plan. [48]

The Park Service's bid on the surplus lands interrupted surreptitious plans between the Bureau of Prisons and Ohio penal authorities to transfer all of the property. As a federal agency, however, NPS had first claim to any excess federal land. The agricultural leasing agreement between the two continued, however, and the only land transfer came in 1971 when 14.75 acres went to the Ross County Board of Commissioners to establish the Camp Sherman Memorial Park at the beginning of Camp Sherman Memorial Highway (State Route 104). [49]

On February 4, 1972, General Superintendent Bill Birdsell secured Congressman William H. Harsha's support to effect the land transfer for NPS. Harsha soon learned from the Department of Justice that CCI and state authorities opposed it. Birdsell wanted to continue using congressional means to achieve NPS goals. "We believe we have an excellent opportunity to round-out the Hopewell Indian culture story" Birdsell reported, "by developing [Mound City Group] into the area its significance deserves and makes it more than just a 'City of the Dead' (pun intended)." [50] Birdsell warned of increasing area industrial development with the advent of flood control programs. He dismissed the Northeast Regional Office's view of "Hopeton is hopeless," that acquisition of the ceremonial and habitation site across the river would never happen. Instead, Birdsell pressed for its addition to the park along with Justice department lands and called for the necessary master plan amendment. [51]

In response to a query from the Northeast Regional Office, Acting Regional Solicitor William H. Thornton, Jr., opined that while legislation was not necessary to complete the federal lands transfer, a presidential proclamation under the 1906 Antiquities Act would suffice. However, the House Interior and Insular Affairs and Interior Appropriations committees let it be known that they wanted NPS to seek legislation so as not to usurp congressional authority. [52]

To produce public pressure for the transfer, in August 1972, Birdsell outlined NPS plans to tell a more complete Hopewell culture story before the Chillicothe Rotary Club. Birdsell held out the promise of picnic facilities if a sufficient land base not in conflict with archeological resources could be secured. On October 14, Congressman Harsha announced 9.27 acres of land in the southeast corner of the VA Hospital's grounds would be transferred to NPS under the Legacy of Parks program. The transfer took effect on November 2, 1972. [53]

In mid-1973, a Denver Service Center planning team led by Robert L. Steenhagen began a study which led to the March 1974 formal assessment of surplus federal land additions. It largely reflected the park and Northeast Region plan from 1969, although it pared down Parcel 2 provisions to exclude an area still desired by the VA, and called it "Parcel 2a." The team recommended that surplus Justice lands be used in an exchange for Hopeton Earthworks. [54] Omaha regional officials accepted the report, but no progress was made to draft legislation. All parties acknowledged that if Ohio needed the land to continue its program at CCI, the legislation would not progress very far. [55]

A meeting with CCI officials in 1976 found resistance to relinquishing agricultural lands to NPS. Superintendent Fagergren pushed for legislation to acquire Parcels 1, 2, 2a, and 4, with consideration given to obtaining either Parcels 5 or 6 to alleviate the park's chronic housing problem. With the dissolution of the Ohio NPS Group, the Denver Service Center's findings in 1974 were no longer valid. He advocated a high-level meeting of all parties to resolve the logjam. [56] In September 1976, the Midwest Regional Office requested legislative support data and materials for Congress. The package that went to Congress in the fall of 1977 was as follows:

Parcel 1: Adjacent to State Route 104, Parcel 1 contained 7.5 acres and a house occupied by a state prison employee, lending itself to employee housing or future park infrastructure.

Parcel 2: 48.85 acres; bounded on the west by State Route 104, and the east by the eroding Scioto riverbank. Parcel 2 contained an unexcavated Hopewell village or campsite. Planners envisioned the tract accommodating the park's residence and utility building, relocated here so as to remove them from their close proximity to the Mound City Group earthworks. Gone from this proposal was any mention of the "ethno-historical demonstration area."

Parcel 3: An east-west strip fifty feet by 2,600 feet containing 3.34 acres along the park's south boundary utility road, cultivation here would cease with grass planted. There would be no vegetative screening.

Parcel 4: Contiguous with Parcel 3 to the prison wall, this buffer strip, used by CCI for alfalfa, measured 350 feet by 3,000 feet and contained 22.4 acres. Continued agricultural lease was recommended.

Parcel 5: A north-south strip immediately west of State Route 104, Parcel 5 measured 200 by 3,800 feet, or 21.59 acres, and used as corn fields. Cultivation occurred to within twenty-five feet of the road and within this strip were powerlines and evenly-spaced silver maple trees. [57] Continued agricultural use was recommended.

The entire proposal constituted 103.68 acres. [58] Continued opposition expressed by the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction stalled the effort. In December 1979, Governor James Rhodes announced plans to construct a new prison on the leased agricultural lands across State Route 104 from Mound City Group National Monument. NPS promptly notified General Services Administration to reserve specific tracts should the Department of Justice lands be declared surplus. The Park Service had already drafted legislation and pushed for its introduction into the second session of the 96th Congress in January 1980. The legislation eliminated Parcel 1 and, with a few minor alterations, the package now stood at 92.23 acres. [59]

While Fagergren advocated presidential proclamation to transfer the land, his superiors continued to rule the action unwise and a disregard of congressional prerogative. The surplus declaration came in April 1980, and Ohio declared its interest in acquiring all lands it already leased. NPS officially notified GSA of its interest in the lands with the promise that if GSA did not set them aside, NPS intended to nominate the significant archeological resources to the National Register of Historic Places, thereby invoking section 106 compliance review per the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. [60] NPS designed the move to slow the process down and prevent surreptitious action.

The presence of the National Register-eligible Hopewell village brought about a June 3, 1980, meeting attended by NPS, GSA, Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Ohio State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), and three state agencies: Department of Mental Health and Rehabilitation, Public Works, and Bureau of Prisons/CCI. NPS was the only federal agency expressing an interest in the excess property. State agency officials, exclusive of the SHPO, were either unconcerned about cultural resources or denigrated them. The meeting revealed state plans to site the new prison on Parcel 4. While Ohio did not object to NPS plans for Parcels 1 and 2, it vigorously opposed them on Parcels 3 and 4. GSA pushed NPS not to request transfer of 3 and 4, instead asking that deed restrictions guaranteeing present use with a reversion to NPS clause should ownership ever change. NPS accepted the compromise if Ohio promised to provide water and sewer service to the area within five years of the transfer. During review of the deed restrictions, NPS insisted on an additional clause on Parcel 4 which gave NPS the right to implement a mutually-acceptable vegetative screening plan with costs borne by NPS. [61]

On December 28, 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed Public Law 96-607 which, in part, expanded the monument and provided for acquisition of the 150-acre Hopeton Earthworks and 52.7 acres surplus to the Justice department (Parcel 1 at 47.16 acres and Parcel 2 at 2.87 acres). [62] Immediate transfer became hampered by two events: the beginning of the Reagan administration and GSA request for a fair market value payment of $72,500 for Parcels 1 and 2. Because GSA did not consider PL 96-607 as congressional direction to it to transfer the tracts without reimbursement, NPS had to seek an exception via a request from Interior Secretary Watt to GSA, with concurrence from the Office of Management and Budget. Watt's request did not come until March 4, 1983, and GSA's conveyance came on April 28, 1983. Under direction of PL 96-607 and the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949, GSA Real Property Division Chief Robert M. Crouse transferred the property "without reimbursement to the Department of the Interior together with a reversionary interest in a strip of land 200 feet wide situated along the west side of State Route 104 and another strip of land 350 feet wide located along the southern boundary of the monument." [63]

Under the historic leasing program, Mound City Group promptly issued an agricultural special use permit to CCI. Park maintenance installed boundary markers, planted shrubs and trees for screening, and instructed the telephone company to move its utility poles. To provide a more effective natural screen, the park stopped mowing the strip adjacent to the agricultural use area. [64] The expansion effort that began in 1969, came to legislative fruition in 1980, and culminated in 1983, with all but Hopeton Earthworks yet to be acquired (see Chapter Ten).

History of NPS Archeological Research

|

| Figure 42: Raymond S. Baby, curator of archeology, Ohio Historical Society. (NPS/Betty White, May 1974) |

National Park Service archeologists who compared the Squier and Davis survey with the restoration work performed by Mills and Shetrone in the early 1920s noticed that the extant configuration differed from the historic plan. An early 1960s report prepared by Northeast Regional Archeologist John L. Cotter made five recommendations to rectify the discrepancy. First, Cotter called for restoration of the borrow pits, one to the north of the rectangular enclosure, the other outside the northeast corner. Second, the earthen wall itself required restoration by finding the cross sections at each corner as well as on the north side. Third, Cotter wanted all mounds that lacked adequate excavation data to be base-tested to verify extant post molds because original mound circumferences were on or slightly within the post mold circles. These included mounds 1, 4-6, 10-11, 14-17, 19, and 21-24. Two small mounds outside the enclosure, north and south of the visitor center, also required verification. Fourth, other mounds needed to be checked for precise location and restored in height and shape per 1848 data. Fifth, Cotter called for the area to be tested again to corroborate 1848 and 1920s claims that no habitation evidence existed within or near Mound City Group.

Cotter recommended that NPS contract the work to the Ohio Historical Society's curator of archeology, Raymond S. Baby. He estimated that the excavation work would require two, six-month seasons, performed by about twenty laborers. Earthen restoration would cost $60,000, including $25,000 for investigation and research. As Cotter first conceived it, the contract would run from May 1963 to October 1964, with a final report due in 1965. [65] As work progressed, however, NPS ultimately expanded the project to span a dozen years.

Funding came almost immediately. The Kennedy administration's Accelerated Public Works Program made available $85,000 in January 1963, and the contract work began May 1. Contract supervisory archeologist James A. Brown from the Illinois State Museum served as Baby's onsite project manager, with Mound City Group Archeologist Richard D. Faust looking after NPS interests. In the first month, the team found the charnel house and a cremated burial of Mound 10 beneath Camp Sherman's Toledo Avenue. Below grade of the charnel house was a subfloor tomb, which in addition to the crematorium, were a copper headdress, adze, and beads, as well as shells and freshwater pearls. Workers subsequently picked up and moved the 1920s Mound 10 reconstruction to its proper location. During the second month, Superintendent Riddle reported his pleasure at increased local press coverage, stating the new finds "have changed a somewhat static [public] attitude" toward the park and spawned increased demand for an interpretive program. Indeed, locals were intrigued by the discovery of a previously undocumented borrow pit near the earthwall's exterior southeast corner that yielded the first skeletal Hopewellian burial ever found at Mound City Group. Placed with the skeleton were nine flint knives. [66]

|

| Figure 43: Excavated Mound 10 revealed a post mold pattern of a structure as well as a ditch associated with a Camp Sherman street, visible as a dark linear stain. (NPS/ca. 1963) |

|

| Figure 44: On the southwest corner periphery, archeologists discovered and restored a previously unrecorded borrow pit. (NPS/John C. W. Riddle, September 1963) |

Work performed in August 1963 ascertained that the entire south earth wall had been incorrectly sited during the 1920s restoration, including its opening leading towards the river. Archeologists did not remove a skeletal burial partially exposed outside the south earth wall because it rested beneath the railroad spur right of way. In September, reexcavation of Mound 13 occurred with the south enclosure wall accurately located thirty-five feet away. Archeologists ascertained Mound 13's true configuration, and restoration of the in situ exhibit, known as the "great mica grave," was deferred until 1964, its outline marked by wood posts protruding a few inches above the restored mound's surface. A "carbon 14" date performed on charcoal from the cremation burial found in Mound 10 produced an A.D. 178, plus or minus fifty-three years, result. The new test provided the "closest and best authenticated carbon 14 date for Mound City Group and one of the key dates for the entire Hopewellian culture." Regional Archeologist Cotter further reported at the conclusion of the first field season:

The work beneath Mound 13 has now revealed two complete charnel house floors, one rectangular and one square with double wall post molds. At the margin of the Mound, but associated with Hopewellian occupation, an extended burial has been found in good condition. The individual has an undeformed head, long in proportion to width, indicating a true Hopewellian physical type.... The outline of Mound 13 has been determined accurately to have been 70 feet rather than nearly 100 feet as reported by Squier and Davis, and its estimated height according to the 70 foot diameter would be 14 feet.

It is now beginning to be apparent that the original placement of the Mounds within the enclosure was symmetrical and with a well-defined pattern rather than the haphazard one apparent to the visitor in the faulty restoration of 1923. Present indications are that when the restoration is completed Mound City Group will take on a far more meaningful appearance and will interpret more accurately the true intention of its builders. [67]

|

| Figure 45: Excavation and recording of Mound 13. (NPS/John C. W. Riddle, October 1963) |

|

| Figure 46: Mound 13 post patterns and remnants of original floors indicated the presence of two structures, one built earlier than the other. (NPS/May 1963) |

|

| Figure 47: Construction of the Mica Grave Exhibit necessitated installation of a vertical panel to reduce glare on the glass. NPS removed this exhibit and restored Mound 13 in 1996. |

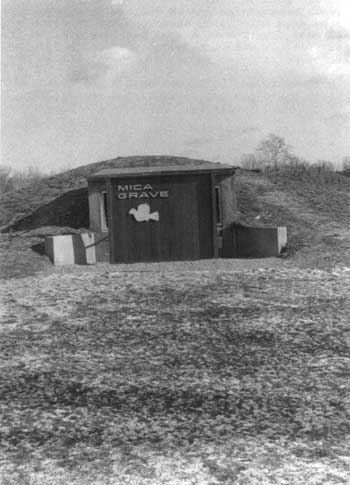

With a six-man crew employed by the Ohio Historical Society and Richard Faust as supervisory archeologist, the second phase of restoration work began on July 29, 1964. Work focused on restoration of Mounds 4 and 5. Excess earth taken from the construction of the great mica grave exhibit, also underway in 1964, went to Mound 4 in addition to a new load of dirt obtained to restore the mound to sixty feet in diameter by three-and-a-half-feet high. Contemporary disturbances at Mound 4 had all but obliterated it, save for post molds and its charnel house. [68]

Construction of the mica grave exhibit concrete structure continued through the winter of 1964-65, with the glass front installed in mid-1965 to reveal in situ ashes in four burial pits. Securing an additional $2,500, NPS extended the Ohio Historical Society's contract to perform additional location work on Mound 5, restore the northwest corner of the enclosure wall, and excavate Camp Sherman debris out of the borrow pit at the same corner. Work on this phase began on September 27, 1965, with new Park Archeologist Lee Hanson overseeing the project. Mound 5 proved to be fifty feet west of where the 1920s restoration placed it, and twelve times larger. The work for this phase ended in early November 1965. [69]

Two Ohio Historical Society reports on the excavation/ restoration work were accepted by NPS in 1966. [70] However, archeological work yet continued. Park Archeologist Hanson, using power equipment wielded by the maintenance crew, restored a borrow pit north of the enclosure wall. Jim Ryan of the Ohio Historical Society assisted in the June 20-22, 1966, work that saw the removal of a large cottonwood tree and fill removed from the pit and stored for use in future restoration activities.

In October 1966, Hanson completed the excavation and restoration of the east gateway in the enclosure wall, with the incorrect gateway filled back in with soil. During the 1920s restoration, a depression caused by a Camp Sherman waterline was mistaken for the opening, while the correct one was filled in. Hanson made two recommendations that he directed be accomplished prior to siting an interpretive trail through Mound City Group. First, one of four mounds along the northern tier should be taken down and its charnel house pattern exposed to enhance visitor understanding. Second, whereas Squier and Davis recorded twenty-three mounds at Mound City Group, and Mills and Shetrone restored twenty-four, the mound in dispute required testing to authenticate it. [71]

|

| Figure 48: Charnel house of Mound 5 appears in center of post molds marked by newspaper. (NPS/Lee Hanson, October 1965) |

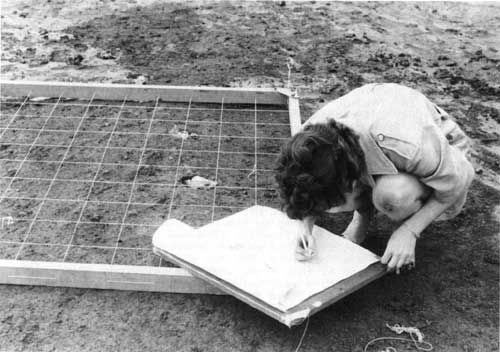

No archeological work transpired during 1967, but resumed in 1968 with the Ohio Historical Society's excavation and relocation of mounds 17 and 23. Directed by Barbara S. Saurborn, the archeologists quickly determined that Mound 23's exact location was just to the south of where its 1920's position had been. Mound 17 took longer to pinpoint, but it was relocated to the southeast and its configuration proved to be larger. Baby announced the significant discovery that the charnel houses of mounds 17, 3, and 23 were in direct alignment through the center of Mound City Group. [72]

|

| Figure 49: Elmo Smalley, Sr., uses heavy equipment to remove Mound 17. (NPS/Nicholas Veloz, Jr., April 29, 1968) |

|

| Figure 50: Ohio Historical Society's Martha Potter plots the post molds of Mound 17. (NPS/Nicholas Veloz, Jr., May 1968) |

With six of the twenty-four mounds verified, NPS wanted to extend the work to include the remaining eighteen mounds. A management appraisal report prepared in early March 1968, called for guidelines for the archeology program that "can be consistently followed by Northeast Regional Office and the changing superintendents and park archeologists." Acting Regional Director George A. Palmer informed Director Hartzog that the 1958 decision to retain Mound City Group was "based upon the premise that it would be an interpretive site. During the interim period it has been demonstrated that there were archeological deposits that had not been destroyed in the past and could be uncovered." Because the 1960's work proved successful in yielding new information, Palmer advocated "a thorough study and recommendation from the Office of Archeology and Historic Preservation" on the park's collection and research policies that constantly shifted with changes in park personnel. He observed the collection included an array of artifacts not directly associated with Mound City Group, gathered by off-duty personnel or donated by citizens. [73]

Ernest Allen Connally, chief of the office of archeology and historic preservation, directed NPS to continue its practice of cataloging artifacts excavated by the Ohio Historical Society, and advocated continued verification of mound locations. He acknowledged that artifacts the society previously excavated were unquestionably federal property, but "to make any real efforts to secure the collection at this time, when our relations... are excellent, would only have very unfortunate public relations repercussions." NPS facilities for curation and research at Mound City Group and Ocmulgee continued to be inferior to the society's. Connally recommended Park Archeologist Nicholas F. Veloz begin compiling an archeological research management plan to address outstanding issues. [74]

Another contract with the Ohio Historical Society in 1969 resulted in mounds 1 and 19 relocated to their original sites. Society employees involved in the effort were Baby, Assistant Curator Martha A. Potter, and Ohio State University students Wayne Haulpert and Steven Stathes, while Veloz and Edward Wolford represented NPS. Phase two, involving mounds 6, 20, and 24, came in 1970. [75]

A fortuitous discovery in 1970 yielded the location of Squier and Davis's field notes along with fifty pictorial plates. Long-standing efforts to locate the materials bore fruit when an astute researcher noticed in a 1954 reference book that the long-lost papers were in the Library of Congress. A request to the manuscript division yielded the response that not only did it possess numerous boxes of Ephraim G. Squier's papers, but it was in the process of microfilming all of it. [76]

Mound 24 testing conducted by Dr. Baby in 1970 revealed no subsurface features, thereby demonstrating that Mound 24 never existed. Mills and Shetrone mistakenly constructed it in 1923. Baby attributed the discrepancy to the Squier and Davis map that depicted twenty-three mounds, while the narrative stated there were twenty-four. In October 1970, workers removed Mound 24, and mounds 6 and 20 were moved slightly to the south to conform to their post hole patterns. In April 1971, excavation and relocation of Mound 12 began. It proved to be the most productive work in terms of artifacts since the investigations began in 1963, an unusual finding since the mound had previously been disturbed and excavated. Mound 12 also proved significant because of its charnel house pattern and single, not double, post holes. Experts speculated that the mound could represent one of the earliest constructed at Mound City Group.

Additional archeological work performed under contract by Ohio Historical Society in 1971 involved mounds 11 and 16, the last of the mounds north of the enclosure's center to be relocated to their true positions. Baby's work uncovered two nearly intact clay pots inserted into two postholes. Mound 11 had a charnel house with a single, not a double, doorway that opened to the east covered with a large canopy. It had nine interior roof supports, not the typical seven. Mound 11 proved to be twenty-five feet north of its original placement, while Mound 16 was only slightly off. Following up on the recommendation first made in 1966, the archeologists advocated Mound 15 not be reconstructed, but to have posts placed in postholes for visitors to see and better comprehend what lay beneath the mounds. [77]

Nineteen seventy-two saw the removal of the railroad spur through the mound group and restoration of the area. Removal of the ballast beneath the rails provided the opportunity to excavate the skeleton of an Indian woman initially uncovered in 1963 while probing for the southeast corner borrow pit. [78]

General Superintendent Birdsell found sufficient funds ($4,500) in the Ohio NPS Group's budget to accomplish research and restoration of Mounds 14, 21, 22, and the completion of interpretive exhibit Mound 15. Dr. Baby found the charnel house of Mound 15 to be rhomboidal-shaped with a north-south orientation directly aligned with Mound 3, which gave additional credence to his theory of mound alignment. Mound 15 proved to be 120 feet east of its 1920s predecessor. Treated wooden posts were installed to mark its post hole pattern, and a May 1974 dedication brought four hundred people to view the new exhibit. During the event, archeologists demonstrated their restoration and relocation methodology to quell persistent rumors that the mounds were being arbitrarily moved about. The same season saw Mound 14's restoration sixty-six feet southwest of its previous site, and among the scattered artifacts were pieces of sheet mica. Workers resited Mound 22 forty-four feet southeast of its previous location. This mound featured the second rectangular charnel house yet discovered. Orientation of the charnel house's long axis was to the west gateway of the earthwall enclosure. In the last project of the 1974 season, archeologists determined Mound 21 to be 180 feet off its correct site and filled with large pieces of Camp Sherman debris. [79]

Commiserate with the shift in NPS regional boundaries brought a move to assign project cost estimates based upon Denver Service Center (DSC)-devised figures. When DSC arbitrarily assigned restoration costs at $15,000 per mound, Birdsell exploded. Citing the Ohio Historical Society's niggardly $3,000 to $4,000 estimates, Birdsell complained to Midwest Archeological Center chief F. A. "Cal" Calabrese, "It greatly disturbs us to have an exorbitant and unsubstantiated amount programmed for each of these excavations when we have on record a lower relative firm estimate to accomplish this work." Birdsell feared that the high estimates would prevent Mound City Group from receiving programmed funds. The park would be forced continuously to siphon money from its own operating budget, supplemented by surplus Midwest Archeological Center monies, to keep its archeological program alive. [80]

Times had clearly changed as the professionalization of what became known as "cultural resources management" occurred in the 1970s. With the burgeoning field of public history thriving, thanks to the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, universities and their allied partners in state historical societies and museums no longer dominated. That meant without traditional subsidization by academia by using students and volunteers, the true cost of such work emerged. With cultural resources management becoming standardized throughout the federal government, the cheap, good old days vanished. In archeology, this became acutely apparent. [81]

The 1975 season proved to be the capstone of the twelve-year archeological program. In the spring, an Ohio State University team of archeologists and anthropologists, led by Raymond Baby, excavated Mound 9 and relocated it ten feet north. In September, Baby's team investigated Mound 8, the site where Squier and Davis in 1846 uncovered nearly two hundred effigy stone pipes. Mounds 8 and 9 were in alignment east to west. Baby noted with the season's work, "major errors have been corrected" in restoring mound alignments at the park. He observed, a "deliberate orientation of the [charnel] house structures" with mounds 23, 17, 19, and 1 aligned 120 feet from one another. Carbon-dating analyses determined structures at Mound 10 at 179 A.D., the south earth wall at 61 A.D., and Mound 17 at 358 A.D. [82]

After 1975, there was only one additional mound excavation at Mound City Group. In early 1975, the Midwest Regional Office discovered activities in its Ohio parks were not in conformance with section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. Section 106 guidelines, promulgated in the early 1970s, provided the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation an opportunity to comment on federal projects determined to affect National Register-eligible resources. With the passage of the 1966 legislation and the creation of the National Register of Historic Places, cultural units of the national park system, including Mound City Group National Monument, were automatically listed on the register. So as not to derail the 1975 season, Cal Calabrese pointed out to the Advisory Council that the work was being conducted by the Ohio state historic preservation officer's own agency, the Ohio Historical Society, and secured a verbal "no adverse effect" determination for work to be performed on mounds 8 and 9. [83]

The section 106 legal requirement coincided with a realization that final archeological reports produced by Ohio Historical Society contained scant administrative, interpretive, or scientific information beyond mound location and size of post molds. Issues of significance within the larger mound complex were not addressed. Upon Fagergren's recommendation, the Midwest Regional Office rejected Baby's report for mounds 14 and 22 until it contained adequate professional content per the purchase order agreement. Further, Fagergren called for Midwest Archeological Center's assistance in clarifying the park's management of its cultural resources, stating, "It is our belief further archeological investigations should not occur unless they can provide information useful to management and interpretation of the area. Past research has done little beyond verifying mounds locations and a greater cost-benefit ratio should be shown for justification of future work." NPS also pressed for Raymond Baby to submit long-overdue reports. Once received, a comprehensive synthesis of all past archeological work would yield research questions to fill remaining gaps in knowledge related to Mound City Group. Only then could responsible archeological excavations resume. [84]

David S. Brose of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History led a survey team in 1976 in areas identified for potential landscaping work to determine the presence of significant resources, and thereby eliminate those sensitive areas from consideration. The survey took place beyond the immediate mound group itself, and yielded conclusive evidence of Hopewellian activity. Brose noted,

A more significant result of these archaeological investigations is their demonstration of the presence of prehistoric Hopewellian activities beyond the walls, possibly associated with the ceremonial activities within the Mound City Group enclosure. Whether such occupation represents domestic or ritual behavior, and whether it is to be associated with some construction or post-construction phase of mound-building Hopewellian cultural behavior remains uncertain given the limited excavation and the extensive recent disturbance of the area. However, it is now clear that models of Hopewellian ritual, subsistence-settlement pattern, or regional exchange cannot justifiably use missing data as true negative evidence for occupation from the vicinity of the major Hopewell ceremonial centers. Hopefully, future archaeological investigations of Ohio Hopewell sites will concentrate less on the mounds for the dead than on the excavation of evidence for the living culture. [85]

Fagergren's discussions with Brose over books for the park's sales area led to a more grandiose scheme for the first professional conference devoted to Hopewell archeology. Held March 9-12, 1978, in Chillicothe, the conference received joint sponsorship by Mound City Group National Monument and the Cleveland Museum of Natural History with an objective of "providing adequate and current regional and topical data for discussion of the Hopewellian complex in Eastern North America." Proceedings of the conference did provide a sales item at the park. [86]

In 1977, the stone steps to the summit of Mound 7 were removed, thus eliminating visitor confusion concerning their origin and resulting in random use patterns within the mound group. Maintenance workers repaired the eroded scar and reseeded the following year. In 1979, excavation of Mound 9, in the program pipeline since 1975, took place and received its correct siting. Bruce Jones and Bob Nickel of Midwest Archeological Center first used a proton magnetometer at Mound City Group in August 1979 on areas to determine magnetic differences between Camp Sherman remains and less disturbed areas. [87]

Working with Martha Otto, curator of archeology at the Ohio Historical Society, Fagergren tracked down long-forgotten purchase orders and firmly pressed for completion of outstanding mound excavation reports. Reports for mounds 11, 12, and 16 were approved for payment in 1980, with the remaining reports on mounds 21 and 24, following soon after. [88]

In 1982, Regional Archeologist Mark Lynott, assisted by Sue Monk, Bob Nickel, and Chris Schoen, surveyed surplus Department of Justice land north of the park boundary designated for addition to the monument. Their survey demonstrated the area contained a significant Hopewell occupation site, most likely related to Mound City Group. Monk's work at the park with faunal remains indicated a disproportionate number of rib cage sections were brought into the mound enclosure, thereby bolstering the hypothesis of Mound City Group not ever having been permanently inhabited. [89]

The report and subsequent work has established that no one previous to A.D. 900 or 1000 in the Eastern United States were true agriculturalists. While the Hopewell may have used maize for gardening, they did not practice dedicated farming. Most Hopewellian peoples practiced a fully agricultural economy, but it focused on a suite of native annual seed-bearing plants. [90]

By the early 1980s, the National Park Service lacked basic data only on Mounds 3, 7, and 18. None of these had been re-excavated since the 1920s, nor had two other mounds to the west outside the earthwall enclosure. The latter mounds were suspected of being 1920s fabrications, approximately sited to mimic mounds which appeared on Squier and Davis' map. Modern archeological methods would certify the authenticity of these unrestored mounds. [91]

James Brown of Chicago's Northwestern University received custody of some of the Mound City Group archeological collections to produce a contracted synthesis of past research and excavation efforts. In response to Brown's concern regarding the condition of the collection, Mark Lynott and Melissa Connor, both of the Midwest Archeological Center, met with him to discuss the issue in November 1983. The archeologists noted mistreatment of the collection by "improperly trained personnel" resulting in "considerable damage to the research value of the collection." Lynott recognized curation and cataloging practices performed on the archeological collections "without insuring that basic provenance information about the artifacts is preserved." The consensus recommendation was either to add a professional archeologist to the park staff to manage the collections or to transfer the artifacts to Midwest Archeological Center to ensure proper care. [92] The curatorial concern remained until the transformation of the monument into a large, multiple unit national historical park. Following a two-decade absence, the park added a term-appointment archeologist to its staff in the mid 1990s.

The combined body of twentieth-century archeological reports related to Mound City Group excavations are of poor quality, lacking basic, detailed information, and in many cases, maps. Contemporary experts find reconstructing an informed history of Mound City Group archeology nearly impossible based upon the hastily-prepared reports, most of which were accomplished by the Ohio Historical Society. This observation applies to most other reports of the pre-1970 period, including those of the National Park Service. Future excavations will have to be based upon legitimate research questions in areas such as chronology and persistent cases of verifying mound placements. [Archeology related to Hopeton Earthworks appears in Chapter 10.] [93]

A minor footnote to the archeological history of Mound City Group is the National Park Service's role in the controversial work of Arlington Mallery related to the mysterious "iron furnaces" found in the western half of Ross County. Intrigued by his search for pre-Columbian stone masonry, Mallery visited Spruce Hill in 1948, discovered what he determined to be iron slag, and began formulating his theory of a pre-Columbian Iron Age in North America. Mallery began excavating more than a dozen archeo-pyrogenic sites, or iron furnaces, and as press coverage spread news of his findings, public curiosity grew. Mallery attempted to lend credence and prestige to his findings by declaring his iron materials would be displayed by the National Park Service at Mound City Group National Monument. Mallery did so in the absence of Superintendent King. Upon his return, King restricted the viewing to scientists and consigned the display area to the maintenance building, thereby limiting and controlling the publicity. In the Chillicothe area, the publicity proved largely negative.

Mallery and his display were at Mound City Group from November 23 to November 30, 1949. Other than a few scientists, no more than twenty-five individuals viewed the materials. Raymond Baby denounced Mallery's findings, stating "The evidence does not warrant any of the claims." Dr. S. L. Hoyt, metallurgist, declared it "interesting but not conclusive." [94] Ralph Solecki of the Smithsonian Institution's Bureau of American Ethnology, in the area conducting river basin surveys along Deer Creek and Paint Creek for flood control along the Scioto, also visited. Solecki even inspected the Mallery sites themselves and denounced the Norse or Viking furnaces as "nothing more than lime-burning pits which probably date from the period of the construction of the Ohio and Erie Canal in about 1835." [95]

Undaunted, Mallery went on to publish his work in 1951 in a book titled Lost America, which gained even more popularity when a related article appeared in National Geographic Magazine. An updated version, co-authored by Mary Roberts Harrison in 1979, eleven years after Mallery's death, was titled The Rediscovery of Lost America. In assessing Mallery's work, David Orr criticized it as "sloppy even by contemporary standards" in that he demolished sites in his zeal for corroborating evidence. Further, Orr charged Mallery "stacked one questionable claim upon another until he could conclude exactly what he had hoped: that the pre-Columbian New World had been visited by a superior race of people--undoubtedly of European" origin. [96]

Although some individuals and organizations still herald Mallery's claims, no professional archeologists have been willing to examine extant evidence or search for more. References and inquiries to Mallery's work, however, still occupy Park Service attention and will continue to do so as long as the mystery of the iron furnaces persists. [97]

Following up on the successful 1978 Hopewellian conference, "A View from the Core" took place in Chillicothe on November 19 and 20, 1993. Co-sponsored by Hopewell Culture National Historical Park and the Ohio Archeological Council, more than 250 individuals attended and heard papers presented by noted archeologists and anthropologists. One session saw Park Ranger Robert Petersen discussing how interpreters convert raw archeological research into material for public education. Participants were also able to tour the new units of the national historical park. [98]