|

Hopewell Culture

Amidst Ancient Monuments The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio |

|

CHAPTER FIVE

Relations with the Community

Since the creation of Mound City Group National Monument, the people of Chillicothe, Ross County, and southern Ohio have demonstrated a strong proprietary interest in this small park area. For those keenly aware of the significance of the place, it represents a source of local pride that a key remnant of the Hopewell culture once flourished there. Likewise, those unaware of its significance have taken a similar pride in the site's anomalous landscape and beauty. More popularly referred to simply as "Mound City," local citizens in the late twentieth century considered Mound City Group National Monument an attribute to the region's tourism-enhanced, post-industrial economy.

From the onset of National Park Service administration, the national monument has taken its role as a member of the community seriously. Cognizant of its contribution to the area's economic viability as well as its mission to help enlighten young and old alike, managers have excelled at cultivating positive public relations. With its small staff and budget, park development and operations have benefitted from community partnerships to fulfill its congressional mandate, including those with other federal, state, and local agencies.

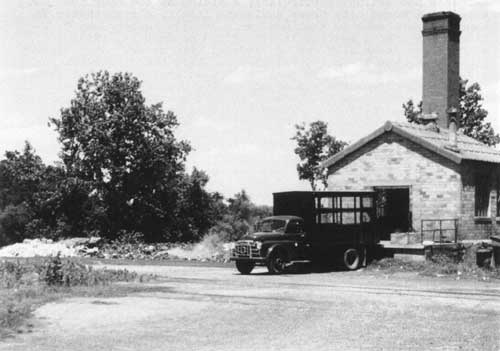

Veterans Administration

One of the closest management relationships Mound City Group National Monument has actively cultivated for five decades is with the Veterans Administration (VA). The VA hospital inherited a large segment of Chillicothe's federal reservation following the World War I-era demise of Camp Sherman. As early as January 1947, Superintendent Clyde King reported the first fire caused by the VA's incinerator building: "The Veteran's Hospital has an incinerator at the northeast corner of this area, just over the boundary. When [the] wind is out of the north or northeast it is not unusual for entire newspapers to come out of the smokestack and ignite while sailing through the air. One of these started a fire which was extinguished before it got beyond the negligible stage." [1] VA administrators were amenable to relinquishing the incinerator and the surrounding 10.5-acre tract. Congressional approval of the land transfer came on April 3, 1952, along with an easement for the VA to continue using the incinerator and its access road until an alternative refuse disposal system became available. In the meantime, landscaping, reforestation, and restoration of a Hopewellian borrow pit by the National Park Service could commence on the new tract as funding permitted.

In the late 1950s as part of MISSION 66-related master planning efforts, Northeast Regional Office personnel focused their attention to solving issues related to Mound City Group, in concert with planned development. Assistant Regional Director George A. Palmer visited in June 1957 to meet with VA officials and discuss not only incinerator and road easements, but the VA's Baltimore and Ohio (B & O) railroad spur line and right-of-way that bisected the national monument itself. Discussions with Dr. H. H. Botts, VA hospital manager, revealed his frustration at not securing funding to move the incinerator building to another location. He welcomed National Park Service efforts at the Washington level to urge VA managers to fund the project. As for the railroad spur, Botts agreed that it should be relocated outside the national monument, but that the National Park Service would have to pay for it. The spur gave the VA a contracting advantage in bids for supplies traveling via rail, and especially for coal to fuel its central heating system. For annual maintenance, Botts estimated the spur required about four thousand dollars and carried 244 railcars. [2]

While an ultimate solution to the B & O Railroad spurline intrusion would have to wait, progress came swiftly on the incinerator. In 1959, the VA commenced its own landfill operation and stopped using its incinerator. In late September, the VA authorized NPS to close the paved access road from State Highway 104, and in January 1960, this same road along the original north boundary was obliterated. In July 1960, the VA declared the building surplus to its needs, and on August 24, authorized demolition. Clyde King lost no time in ridding his park of the eyesore. By the end of September, a contractor razed the building and restored the site to natural conditions. [3]

|

| Figure 51: Veteran's Administration incinerator within Mound City Group National Monument's boundary. (NPS/1956) |

War Department funds paid for the 1920s construction of a spur from the B & O's mainline in Chillicothe north across the Federal Reformatory, Mound City Group National Monument, and terminating at the VA hospital. B & O operated the spur under a revocable permit. As National Park Service officials explained the need to have the intrusion removed in time for the visitor center's dedication, particularly a siding of the spur that cut across the Mound City Group enclosure itself, a sympathetic VA expressed its need to continue use. Superintendent John C. W. Riddle convened a meeting in his office on June 14, 1963, to discuss the issue with the VA, Federal Reformatory, Ohio Highway Department, and the B & O Railroad and laid the groundwork for eliminating the spur. In April 1965, two hundred feet of rails were detached from the siding of the B & O spur that bisected the mound enclosure. VA maintenance workers completed the cleanup of railroad ties the following month, filled in the cuts, and landscaped the grounds to the park's satisfaction. [4]

Final removal of the entire railroad spur through Mound City Group took another six years. In 1970, the VA began installing a gas-fired boiler to replace its coal-powered heating plant, thereby obviating use of the spur. VA hospital director Benjamin S. Wells requested that Superintendent George F. Schesventer put the National Park Service's request for the spur's removal in writing for the benefit of Wells' national managers. In his letter, Schesventer argued that a significant burial discovered under the tracks could not be removed. Because the railbed remained, funds could not be programmed to continue research and interpretive development. Finally, rising visitation increased chances for an accident and subsequent tort claims against both agencies as long as the hazard remained. [5]

Schesventer's effort succeeded. On June 16, 1970, Wells informed Schesventer that the VA would not require use of the B & O spur after September when the new boiler plant went on-line. Conditional to the line's removal was the VA's need to dispose of a crane and coal car already declared surplus. Problems with the conversion from coal to gas and surplusing the equipment caused a one-year delay. During the summer of 1971, the B & O spur permit was revoked, and the VA and National Park Service worked cooperatively to remove the tracks and railbed within their respective boundaries, and to revegetate the scar. Because the Chillicothe Correctional Institute required use of the spur from the B & O mainline, its part remained intact. [6]

|

| Figure 52: Baltimore and Ohio Railroad spur line bisecting Mound City Group earthworks. (NPS/late 1960s) |

Monument staff became adept at steering away from park visitors those mentally unbalanced patients who occasionally wandered away from the VA hospital's neuro-psychiatric facility. Visitors reported one man in November 1962 wandering the mounds wearing a gun. Rangers found upon investigation the man wearing a toy pistol placed in a shoulder holster. In August 1968, a patient found his way to the maintenance utility building where he was given a soft drink and a cigarette, and to further mollify him, the superintendent's four-year-old son, Carl Schesventer, entertained him until VA orderlies arrived. Such patients were usually easy to identify because they were dressed in white clothing. Some met tragic deaths by attempting to swim the Scioto River. On February 19, 1984, one VA patient drowned on the monument's eastern boundary. On May 7 the same year, another patient was discovered floating downstream only semi-conscious. In 1989, yet another psychiatric patient cut his own throat while on park property, but his suicide was thwarted by VA police officers. [7]

Water and sewage treatment services for all government installations on Chillicothe's federal reservation were supplied by facilities at the Federal Reformatory. In the fall of 1966, this free service ended as the facility converted to a central water softener plant with metered service. National Park Service usage was set at 200,000 gallons per month and, based on total output, the charge came to $20 per month, plus a sewage treatment fee. The change came just prior to the state's conversion of the prison into the Chillicothe Correctional Institution (CCI) in December 1966. Managers negotiated a contractual agreement between CCI and Mound City Group National Monument during 1967. [8]

Securing an independent water supply became of prime importance in the early 1980s and prompted both agencies to find a common solution. Both the VA and national monument's water supply system was dependent on the Federal Reformatory and its successor, Ohio-owned and operated CCI. When the federal penitentiary transferred to the state, the VA agreed to find its own water supply, but continued to use CCI's sewage system. Increased water demands from the second prison built across State Highway 104 mandated not only the VA, but Mound City Group National Monument to look for new water sources. One option was to get water from the Ross County Water Company, but the utility lacked funds to build new lines to reach these potential customers. Preliminary park plans called for drilling a well at the maintenance area and establishing the monument's own system, complete with a small treatment plant. Another viable solution called for the two agencies to work together to solve the water dilemma. Because of the prohibitively high cost for obtaining water from the local utility company, VA engineers advocated drilling their own wells, using the existing VA water treatment plant, and permitting the national monument to tap into the VA system utilizing existing lines for a nominal fee. Ken Apschnikat recommended deferring a decision until VA planning progressed further. [9]

In the meantime, Apschnikat arranged to secure sewage and water for fire protection lines and irrigation purposes only from CCI. Agency managers agreed to maintain the $240 annual fee established in 1974 as a baseline sewage charge figure. In 1986, the monument installed a meter and shutoff valve on the CCI water line entering the maintenance shop. [10]

Test drilling for water on VA land proved unsuccessful. Hydrologists determined the aquifer from which CCI drew its water existed between the east side of State Highway 104 and the Scioto River, within the national monument. In April 1985, the VA began pressing the National Park Service for permission to drill test wells within park boundaries. Omaha officials determined that Superintendent Apschnikat possessed the authority to allow ingress to the VA, but urged the conditions be spelled out in advance, including following the advice of Midwest Archeological Center in Lincoln, Nebraska, in order to stay away from significant, subsurface cultural resources. Initially, Midwest Regional Office cultural resources specialists pressed the VA to conduct section 106 compliance review under the National Historic Preservation Act, and stipulated keeping drilling, well lines, and all construction activity within the abandoned railroad bed corridor. The land upon which the wells were to be drilled would be leased, not transferred, to the VA. Upon closer examination, Omaha officials quickly withdrew approval and asked Apschnikat to approach the VA with new concerns. [11]

In mid-June 1985, Apschnikat informed his counterpart that the tract in question, added to the national monument in 1982 because of a Hopewellian habitation site, possessed automatic National Register of Historic Places designation as a component of Mound City Group National Monument. The amount of ground disturbance required to drill a number of wells and to lay water and utility lines once potable water was found could have long-term impacts on significant archeological resources. Apschnikat urged the VA to exhaust all other alternatives, including adjacent state land, before considering National Park Service property. [12]

Three months later, VA officials were back with the same request. CCI refused to consider such a proposal, citing its own agricultural and facility expansion needs. The VA proposed moving the test drilling to the heavily disturbed gravel pit area in the monument's northeast corner where there were no known resources. Section 106 compliance, accomplished through the Midwest Regional Office, resulted in a "no effect" determination. A special use permit issued in January 1986, authorized VA drilling in the old gravel pit. By mid-February, drillers found a sufficient water supply and the VA requested an interagency agreement be negotiated to allow installation of production wells and water distribution systems. Negotiating the agreement took most of 1986 to achieve, with the National Park Service unwilling to grant an easement. Protection stipulations that would normally be written into an easement were incorporated into the final interagency agreement signed in November 1986. [13]

A primary component of the interagency agreement, for the VA to extend use of its facilities and certain privileges to National Park Service employees in exchange for obtaining one hundred thousand gallons of water per day, was estimated to save the small park's budget up to three thousand dollars annually. The 1986 agreement only formalized a practice that was already in place. In fact, the close association and special relationship dated to the days of Clyde King who found he could always rely on the VA to loan equipment or provide a critical service. In 1964, the VA began providing exams and licensing Mound City Group employees with government drivers' licenses when the first park assigned vehicle arrived. VA firemen and equipment responded to park fire alarms and drills, and staged cooperative fire prevention activities on monument grounds. In 1979, the VA's gymnasium became available to park employees two mornings each week. In 1983, permanent park employees were invited to join the VA's credit union. A year later, the monument issued a special use permit and joined the VA in staging what became an annual disaster drill on monument land. In 1986, the VA installed a special crystal on its radio system permitting expanded monitoring and radio communication with National Park Service law enforcement rangers, a service that became especially vital during emergencies and after park operating hours. [14]

Within the first year of the agreement, the monument received the loan of heavy equipment, locksmith services, road striping, welding services, hazardous tree removals, access to training programs, and VA employee association membership. In 1988, VA police joined park rangers in investigating an attempted burglary at the visitor center. The aforementioned services continued, but also included film processing, vehicle and equipment repair, metal shop services, and grounds and landscaping support. In 1989, the VA surveyed and produced drawings for a new sewer line, provided a dethatching unit for the lawn areas, took air samples to test for asbestos, and repaired the visitor center's door. In 1990, VA surveyors worked at the Hopeton unit to establish and re-establish park boundary markers. Coordination between the two agencies remains remarkably intimate. [15]

Prisoners as Neighbors

Mound City Group National Monument enjoyed equally close relations with the Chillicothe Federal Reformatory, administered by the Department of Justice, from the post-World War II era until December 1, 1966, when the facility transferred to state control and subsequent ownership. As with VA psychiatric patients, the monument experienced unexpected visits from escaped federal convicts causing periods of extreme excitement and anxiety at the otherwise quiet, pastoral area. The maintenance utility building and superintendent's residence were within sight of the federal prison's lookout towers. Located immediately to the south, guards with binoculars and high-powered rifles could easily survey much of the national monument. One of Custodian Clyde B. King's first meetings with the warden concerned National Park Service plans to reforest the park, and whether changing the area's common grassland and cultivated farm field landscape might meet with the Federal Reformatory's opposition. While not expressing any objection to the plan, the warden noted that there were other forested areas nearby, especially along the Scioto, and that escapees always tended to head for the nearest woodland for cover. As the park grew more forested to reflect its prehistoric Hopewellian landscape, it might become a primary initial destination point for escaped prisoners. [16]

As long as the prison remained a next-door neighbor, park managers perpetually feared that visitors, employees, or family members might be taken hostage, killed, or have their vehicles hijacked. The apprehension began on September 2, 1952, when a riot at the institution drew heavy traffic and a crowd of spectators outside the prison entrance on State Highway 104. Bureau of Prisons personnel put down the uprising without experiencing any escapes. On December 15, 1962, on a Saturday morning, three inmates staged a break-out from the main compound. Two men were apprehended at the park's boundary fence, while the third sprinted to the mound enclosure area before two guards collared him. [17]

The 1963 incident prompted John C. W. Riddle to purchase a pistol for protection against desperate escaped convicts. Because the park lacked commissioned law enforcement rangers and no one else on staff had firearms training, the gun and its ammunition remained safely tucked away in the superintendent's combination safe. The break-out also prompted a Bureau of Prisons employee to appear in the visitor center lobby to conduct a special briefing on safety and security measures for Mound City Group employees to observe while working in the shadows of the Federal Reformatory. The recommendations came in handy as another escape by three prisoners came during the late afternoon of February 25, 1965. One prisoner was shot and killed upon crossing the open farm field and reaching Mound City Group land. Another man simultaneously halted at the fence, having been shot in the lower abdomen. The third convict darted behind the utility and residence buildings, then sprinted for the west bank of the Scioto where a dozen guards recaptured him. [18]

Numerous escape attempts characterized the mid-1960s when the federal prison downsized in anticipation of its transfer to state control. On May 3, 1965, a group of inmates commandeered a private contractor's pickup truck to punch through the main gate only to become involved in a head-on collision with a Federal Reformatory truck approaching from the outside. Inmates hijacked yet another prison-owned truck and sped west away from Mound City with prison guards in hot pursuit. Park employees watched the activity from the visitor center's office area, relieved that the danger did not involve them. On the evening of July 26, two inmates walked unobserved away from a grass-cutting crew, only to be recaptured the following day in Circleville, Ohio. Thirteen months later, on August 26, 1966, four prisoners tried to climb the rear fence as guards fired their automatic weapons. Three immediately surrendered, but the fourth scaled the barrier and ran to the wooded area along Mound City Group's riverfront. The escapee was apprehended the next day in Chillicothe. [19]

While Mound City Group's water and sewage needs were initially controlled by the prison, so, too, did its electricity come from the same source. This dependency became acutely apparent at 5:20 in the evening of January 19, 1951, when the park's electrical current stopped flowing. Utility workers at the Federal Reformatory traced the problem to the underground high tension lines. Six days later, they determined that not only had a previous splice deteriorated, but the line had shorted out at three other known points. Buried four feet beneath grade, any repairs would be temporary on the decaying line. The prison lacked the funds to repair the line, and advised Clyde King to negotiate with the local power company to provide electricity. The Columbus and Southern Ohio Electric Company constructed a quarter-mile line from State Highway 104 along the park's south boundary to the utility building and residence. After one month living and operating without electricity, the new lines were activated on February 19, 1951, and the park began purchasing its power from the local utility company. [20]

While the area's three federal agencies cooperated on fire protection, the Federal Reformatory exercised exclusive maintenance of Mound City Group National Monument's pre-MISSION 66 road system. This constituted Portsmouth Road, the common boundary road. Under an informal agreement, the prison maintained the gravel surface and park maintenance workers mowed the roadside. In 1957, the National Park Service surveyed and installed boundary markers in the area. In mid-1964, the prison's warden told Superintendent John C. W. Riddle that Portsmouth Road was superfluous to the prison's needs as it had built its own periphery road for patrols and it lacked funding to provide upkeep on Portsmouth Road. Henceforth, maintenance of the rough road, perennially dusty or muddy, was Mound City Group's responsibility. [21]

Close relations continued with state prison managers of CCI. State prison patrols continued the practice of including the visitor center loop road on their routine patrols, particularly during the evening and nighttime hours. Park rangers began using CCI's indoor firearms range in 1977, and attended training sessions there. [22]

Escape attempts continued under CCI management and prompted General Superintendent Bill Birdsell to issue emergency procedures in the event of a prison break. The official park policy read as follows:

1. As a preventive measure, employees will remove keys from all vehicles left unattended. This includes Government vehicles as well as personal vehicles.

2. Upon notification of an attempted escape, or the suspicion of one, the person notified will inform the park staff. Staff members are to be alerted in this order: General Superintendent, Interpretive Specialist, Administrative Assistant, and Maintenanceman. A telephone call will be made to the quarters (774-1356) to notify the occupants there to lock all doors and to take cover. A similar call will then be made to the Interpretation-Maintenance Office to alert all employees on duty in that building to take cover in the basement office.

3. The responsible employee on duty in the Visitor Center will warn all visitors and employees on duty to stay inside the Visitor Center building. Immediate contact will be made with visitors on the grounds, through personal contact and/or the use of the megaphone, directing them to return inside the Visitor Center in an orderly manner and without running.

4. In the event of gunfire from the towers, visitors and employees must be cautioned against exposing themselves or attracting gunfire while running for shelter. During gunfire, employees and visitors on the grounds are to take immediate cover on the north side of the nearest mound or earthwork, until conditions are such that it will be safe for them to be brought inside the Visitor Center.

5. When all visitors and employees in the area are safely within the Visitor Center, all outside doors will be locked. An employee will stand by in the lobby to allow entry to uniformed law enforcement personnel or late arriving visitors.

6. The responsible employee in the Visitor Center will call CCI to notify prison security of the situation at [Mound City Group], and to request notification when the situation is under control.

7. Visitors and employees will not be allowed to leave the Visitor Center until word is received from CCI authorities that the area is safe. When notification to this effect is received from a CCI official, the Interpretation-Maintenance Office and the quarters will be notified by telephone.

8. Under no circumstances will National Park Service employees attempt to apprehend, or assist in the apprehension of, escaped prisoners. Our responsibility rests solely in the protection of visitors and employees. The apprehension of escaped prisoners is the responsibility of trained law enforcement officers, and this will be handled under CCI direction. To repeat, the safety of park visitors and employees takes precedent over all other responsibilities. [23]

The policy remained in effect during a December 1979 attempted escape which CCI guards thwarted a fleeing inmate a mere thirty feet from the monument's south boundary. The cooperative relationship between CCI and Mound City Group became formalized in a memorandum of agreement signed in August 1983. The agencies pledged cooperation in the event of prison breaks, and in exchange for continued CCI patrols in the park, the monument permitted its grounds to be used for observation posts and staging areas in the event of a prison riot or breakout. [24]

On August 27, 1982, the Department of Justice transferred all of its 1,200-acre holdings in Chillicothe's federal reservation area to CCI for $8.4 million. Ohio corrections officials announced beginning of construction in 1983 of the proposed "CCI 2" to ease the state's overcrowded prisons. Located across State Highway 104 from "CCI 1" and Mound City Group National Monument, the new facility was conceived to replace the Columbus Correctional Facility, itself under court-order to close by the end of 1983. In mid-October 1982, CCI Superintendent Ted Engle and employees of the state's contractor, George S. Voinovich, Inc., of Cleveland, met with Ken Apschnikat to discuss the project and its impact on the national monument. The group devised a screening plan along State Highway 104 opposite Mound City Group National Monument within the two-hundred-foot buffer specified in the land transfer deed. While the extant treeline and powerline would remain, new vegetation introduced to fill screening gaps had to be compatible with the powerline's height and not interfere with the highway right of way. [25]

A change in the Columbus Statehouse, budget cutbacks, and a redesign exercise combined to delay groundbreaking for CCI 2 until 1984. During construction, Mound City Group experienced severe littering, boundary encroachments, noise, and blowing dust. The single-building style of prison, favored in the post-World War II era, gave way to the 1980s predilection for multiple buildings. CCI 2 became two, five-hundred-bed residential structures united by a common services and classroom area. The $52 million facility, completed in the spring of 1985, also included a minimum-security honor dormitory accommodating 250 inmates. Unlike CCI 1, it had no guard towers, only "security devices" on the perimeter and two fences crowned with razor-ribbon wire. Alarms were also installed in the elaborate fencing along with twenty-four-hour perimeter patrolling. The official ribbon-cutting ceremony for the "Ross Correctional Institution" came on March 27, 1987. [26]

Close cooperation and coordination between prison and park officials characterized the 1980s. CCI workers removed the monument's abandoned underground oil tank using a CCI-owned front-end loader in July 1982. CCI also removed the old telephone poles and lines along the south boundary in 1983. Also in 1983, the park issued a special use permit to CCI to continue farming alfalfa on 35.5 acres of newly-acquired monument land known as "the North Field." The following year, CCI agreed to the local electric company removing overhead electric lines north of Portsmouth Road onto CCI land. In 1989, Superintendent William Gibson negotiated and signed a memorandum of understanding with Ross Correctional Institute based on the similar agreement with CCI covering emergencies, patrols, and alarm responses. Gibson amended the original agreement with CCI to include agricultural uses on the North Field in exchange for the visitor center's connection to CCI's sewage disposal plant. [27]

Recognizing the abysmal quality of the park's well water, negotiations in 1993 yielded progress in agreement to connect with one of the prison's water system. A 1994 memorandum of understanding with Ross Correctional Institution granted it the privilege of haying 130 acres at Hopeton Earthworks in exchange for Mound City Group connecting to its water system. [28] This arrangement was cancelled in 1998.

Ohio State Agencies and Other Management Partners

Along with the Ohio Historical Society and state prison authorities, Mound City Group managers have also cultivated close relations with the Ohio Highway Department. When highway workers installed new road signs in the Chillicothe area during the summer of 1948, Clyde King inquired why Mound City Group National Monument directional signs were not also positioned in light of new signs for the VA and Federal Reformatory. King requested from the highway division engineer four signs and received assurances that the signs would be manufactured. After the onset of the Korean War, King learned that while the signs were made, installing them would be delayed because of the national steel shortage. In the meantime, in March 1951, the highway department graded the road from the highway to the utility building, but budget and manpower prevented any regrading in 1952. Following the Korean War, King again contacted the Ohio Highway Department concerning proper directional signage, stressing the increasing numbers of tourists who relied upon state highway maps and local signs to find the monument. King learned that while the original order had been cancelled, a new order would be executed. Finally, in March 1954, six signs at three different points were installed directing visitors to Mound City Group National Monument. [29]

State highway crews painted a yellow centerline stripe at no charge from the visitor parking lot to the park entrance in 1964. Upon Superintendent James Coleman's request for increased motorist safety, the highway department also painted a solid yellow stripe indicating a no-passing zone on State Highway 104 approaching the monument's entranceway. [30]

In 1984, to commemorate State Highway 104 as "Camp Sherman Memorial Highway," the department installed a special marker just inside the entrance gate. The redesignated Ohio Department of Transportation worked cooperatively with park and local groups to reestablish the tree-lined historic Camp Sherman-era landscape by replacing the highway's canopy of silver maples. Saddened by abrupt removal of decayed, damaged, and diseased trees, the community coalition launched the tree-planting project in 1990. [31]

With impetus from the park's active safety committee, concern over road safety developed during the superintendency of Ken Apschnikat. The monument suggested a number of measures to improve motoring conditions in the area. To alleviate a growing number of visitor complaints, Apschnikat requested the department in 1985 install monument directional signs at the junction of U.S. Highway 23 and 35 to the northeast of Chillicothe. Because of the monument's comparatively low visitation figures, state engineers refused to honor the request. [32]

Issues related to parks, recreation, and tourism in the Chillicothe area usually involve participation and professional input from NPS. These issues, closely related to the park's mission, necessitated forming partnership relations between all levels of government. Mound City Group lent its support to local and state efforts to develop Mount Logan State Park in the mid-1960s. During the 1965 visitor season, the first exchange of evening interpretive campfire programs occurred between the area's state parks and Mound City Group. Superintendent John C. W. Riddle served as an instructor at the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Parks and Recreation's annual Regional Interpretive Training Program at Pike Lake State Park in April 1965. Natural and cultural resource preservation were primary agenda items the following year as Superintendent James Coleman attended meetings of the South Central Ohio Preservation Society, serving Ross, Vinton, Pike, and Jackson counties. [33]

Perhaps the most vexing issue confronting Mound City Group managers entailed how to accommodate or deflect requests for use of monument grounds for special recreational events. Many activities simply did not lend themselves to the monument's mission of preserving and interpreting the Hopewell culture. Like the persistent local demand to have picnicking facilities, this and other recreational uses emerged from decades of local visitor use that the public fully expected to continue. Each year came requests to hold Easter egg hunts. While this innocent activity used to take place atop the mounds themselves, following park development in the early 1960s, the groups of young children searching for colored eggs and candies were accommodated on the mowed lawns of the visitor center. In 1966, James Coleman directed it be moved away from areas of heavy visitor use and the Chillicothe Child Guidance Club was the first to hold its annual egg-hunt on the lawn behind the superintendent's residence. [34]

Because the growing area needed more recreational space, Coleman participated in the August 1966 formation of a tourism promotion group attended by representatives of the Optimist Club, Chamber of Commerce, Adena State Memorial, Ross County Historical Society, Mead Paper Company, Ross County Automobile Club, and the Ohio Historical Society. Eugene Rigney of the Ross County Historical Society made it clear to the attendees of the key role Mound City Group National Monument played in the area's tourism economy. Rigney set forth his agenda for what the National Park Service should accomplish, including building a "Treasury Room" to display Mound City Group artifacts held at the Ohio Historical Society Museum, acquire land to construct a memorial to Camp Sherman, and rebuild the old picnic shelter. Rigney related his nagging fear that the monument could one day be turned over to the state, a move that he strongly opposed.

While Coleman could only refer local park proponents to the monument's master plan, the dilemma for providing nearby green space for egg-hunts, picnicking, and other recreational activities again presented itself during Bill Birdsell's tenure. Deflecting the activity to a more appropriate off-site area, Birdsell eagerly committed National Park Service technical assistance to the planning and development of Ross County's Camp Sherman Memorial Park. Philadelphia Park Planner Barry Bohnet visited the area in October 1973 to draft a plan for the new county park. Birdsell served as a member of the Camp Sherman Memorial Committee and focused all chronic efforts at siting World War I memorials and picnic shelter houses to this new park located on State Highway 104 between Chillicothe and the national monument. The county park also featured remnants of the defunct Ohio and Erie Canal. [35]

In order to explain fluctuations in visitation patterns, John C. W. Riddle asked the U.S. Weather Bureau in October 1962 to install a weather station at Mound City Group National Monument for daily monitoring by park staff. Regional weather reporting came from Columbus, with only precipitation recording in Chillicothe. While the U.S. Weather Bureau rejected the request for an official weather station, it did install a rain gauge in an area north of the visitor center. On February 15, 1963, Mound City Group began recording daily precipitation statistics for the U.S. Weather Bureau. [36]

In 1972, Mound City Group employees were monitoring another new gauge mounted atop a high concrete tower on Chillicothe's Riverside Street. Considerable risk was involved in reading the gauge as one had to climb a metal catwalk to the tower's midpoint, then take a iron ladder to the tower's pinnacle. Because of the danger in winter due to snow and ice conditions, two employees had to be dispatched to ensure safety procedures. By the mid to late 1970s, the National Park Service regularly provided daily weather statistics from a monument-based class B weather station to three local radio stations, a cable television company, the Chillicothe Gazette, and an area factory. By the early 1980s, Mound City Group employees were monitoring a precipitation and water-level gauge on the Scioto River for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. An equipment update of the class B weather station came in early 1985 when the National Weather Service installed an electronic temperature reading unit in the visitor center office area, replacing the alcohol and mercury thermometers. The device eliminated the daily excursion to the weather station to gather data, effectively saving twelve to fifteen man-hours annually. [37]

The State Coordinator Program

As the National Park System experienced its most expansive growth during the 1960s, Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., debated how best to inculcate the agency's mission and core values into the American mindset. In the political realm, Hartzog believed that political contacts should be made not only at the regional office level, but at the park superintendent level as well. Park managers were encouraged to meet with local, state, and national political leaders and educate them about National Park Service programs and goals. To this end, Hartzog ordered a nationwide initiative that he called the "State Coordinator Program." Upon the recommendation of his regional directors, Hartzog appointed a National Park Service superintendent in each state to be his "eyes and ears" and requested monthly reports be submitted to him.

On October 23, 1967, Hartzog appointed George Schesventer as Ohio State Coordinator, and explained the importance of his new post as follows: "The importance of this vital assignment is to develop a better public understanding of National Park Service objectives and policies and to improve liaison and coordination between the Service and the various government and non-government agencies and organizations as well as influential individuals within the state. Our accent should be on a program that will lead to an improved attitude of cooperation and mutual understanding our respective interests." Hartzog instructed Schesventer to meet with the governor and top state officials as well as contact members of the congressional delegation, and arrange meetings with them both locally and in the nation's capital. Emphasizing his intense interest in the nationwide initiative, Director Hartzog called the assignment an "extremely important and sensitive responsibility." [38]

Ohio's state coordinator duties conducted out of Mound City Group National Monument went so well that it contributed to the management decision to form the Ohio National Park Service Group based in Chillicothe. General Superintendent Bill Birdsell took the state coordinator duties to heart and perfected it to an art form, using his gregarious personality to engender public and political goodwill towards the agency. Birdsell devoted the majority of his time to the program and became the most visible National Park Service official in Ohio. Upon the shift in regional boundaries in 1974, Birdsell literally became the Midwest Regional Office's "keyman" for Ohio as the Omaha office had never before had a system of established contacts in the state. Birdsell's power and influence as general superintendent and state coordinator grew exponentially, garnering for Mound City Group increased attention. His success netted him the job as first superintendent at Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area, the first sizeable national park area established in Ohio in late 1974. Birdsell took his state coordinator's designation with him to the Cleveland area, but following his fatal heart attack in 1980, the duties reverted back to Mound City Group National Monument. [39]

Mound City Group superintendents performed important tasks beyond their park's boundaries even in the absence of the state coordinator's role. James Coleman spent several months in the spring of 1966 preparing the history section of the Ohio River Basin Comprehensive Survey, a cooperative planning effort ordered by Congress between the Department of the Interior and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. [40]

Another important planning effort involved the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center at Wilberforce, Ohio. The concept for a facility to house the premier interpretive display of the Negro experience in the United States began in the 1960s and centered on Wilberforce, a southern Ohio town with seven stations on the Underground Railroad and home to two historically black colleges: Wilberforce and Central State universities. In 1972, the Ohio legislature authorized a planning council to assist the Ohio Historical Society in developing an operations plan for such a center. In 1976, Congress authorized the National Park Service to conduct a suitability and feasibility study that began the following year with Superintendent Fred Fagergren serving on the six-member team. In mid-1979, Acting Assistant Secretary of the Interior Richard J. Myshak recommended against national museums outside the Smithsonian Institution with its existing National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. Nonetheless, members of the Ohio congressional delegation submitted bills calling for the establishment of "Wilberforce National Historic Site" in the 95th Congress with the Col. Charles Young house, a national historic landmark, the centerpiece of the proposed park. By the end of the session, however, this provision was deleted from the omnibus parks bill, and only called for National Park Service technical assistance to a national commission established to study the federal government's role in developing the Wilberforce center. [41]

Ohio's plan for developing the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center came in three phases, and eventually included archives, libraries, and art galleries. It envisioned Wilberforce as the national center for African-American studies and research. With a cumulative pricetag set at well over $25 million, ground-breaking for the first phase came in January 1983, and future construction phases became dependent on the success of private fund-raising.

Ken Apschnikat represented the National Park Service at the facility's dedication on April 16, 1988, and reported on the numerous calls he heard for federal funds to continue operations. In 1991, those efforts at gaining federal funding took the form of H.R. 1960, which called for federal construction and operating dollars. The National Park Service opposed the action, citing duplication of the Smithsonian's mission and maintaining out of self-interest that the center remain non-federal. Midwest Region officials feared that connecting the Wilberforce facility to the National Park Service's budget would siphon off considerable resources and adversely impact the national park system. With the federal deficit and calls to balance the budget in the early 1990s, the National Afro-American Museum and Cultural Center found itself existing on donations and static state funding, unable to expand its collections, and without a training center. Federal operating funds were not forthcoming. [42]

State coordinator responsibilities also meant participating in regional and local organizations. In 1980, Mound City Group National Monument joined the Chillicothe-Ross County Chamber of Commerce and park managers began attending regular meetings to promote community cooperation. Fred Fagergren also joined the newly-formed Southern Ohio Travel and Tourism group to promote regional attractions and events through a membership of thirty-five organizations. In 1982, Ken Apschnikat was named to the chamber's Visitors and Convention Bureau and served in a number of capacities including its board of trustees, ensuring that the national monument figured prominently in local promotional publications. [43]

Apschnikat revived the high profile status of the state coordinator's program role and began including it in his annual reports in 1982 in which he noted thirteen separate actions. In 1984, he joined the Ohio Parks and Recreation Association in order to interact on a professional basis with state parks professionals. Before leaving the area, he observed: "The state coordinator duties are not extremely demanding due to low key activities for the NPS in Ohio. The greatest amount of involvement comes in trying to promote the NPS image and parks in the state. Because the five parks are not extremely well known the challenge comes in promoting these lesser-known parks." [44]

One of the means to promote awareness of Mound City Group came in the form of media relations. During the 1980s, numerous radio stations and independent film companies came to the park as did the Educational Television Association of Metropolitan Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati, and Wilberforce television stations, "Odyssey" of Public Broadcasting System, National Geographic Society, and British Broadcasting Corporation. Rapport with local media outlets remained exemplary with only rare occurrences of misinformation or biased reporting. In 1990, the monument established close relations to a local cable television station interested in broadcasting the monument's interpretive programs and messages for increased community outreach. [45]

In an admirable partnership to provide child care in the Chillicothe community, Mound City Group National Monument joined with four other organizations to form the Interagency Employees Child Care Task Force in 1987. Apschnikat joined with the Veterans Administration Medical Center, Chillicothe Correctional Institute, Ross Correctional Institution, and Union-Scioto School District to obtain grants to provide reliable, affordable child care services close to the workplace. The five agencies represented 2,400 employees, and in late 1987 the task force began searching for a suitable facility to begin services. The Interagency Child Care Center opened its doors in building 212 at the VA Medical Center and by 1989 accommodated 130 children and employed eleven full-time and five substitute employees. Its success made the rural day-care facility a model for Ohio. Because of his involvement in this local effort, Ken Apschnikat received an appointment to serve on the National Park Service's Youth Educational Programming and Day Care Task Force in 1988. The group developed a range of recommendations to help address agency child care issues. [46]

Plans that began in the 1970s for bicycle and hiking trails in the area gained impetus in 1980 when the chamber of commerce called for the acquisition of land adjacent to Yoctangee Park to provide trail linkage from Mound City Group National Monument through Yoctangee Park to connect with the flood levee biking and hiking path near North Bridge Street. The VA Hospital simultaneously expressed interest in joining the trail network. The effort gained further notice because of the Federal Highway Administration's Bicycle Grant program making federal funding available to state and local governments to construct bikeways. [47]

The initiative mushroomed in the late 1980s as a "rails-to-trails" project formed to utilize abandoned railroad rights of ways in three counties. Superintendent Bill Gibson took the lead in advocating the program because many of the Hopewell sites under consideration for addition to the federal park passed near or through them. Gibson's strategy was that the trails network would help link together the noncontiguous sites as well as help engender support for their preservation. Gibson worked to patch together a tri-county rails-to-trails project encompassing Ross, Highland, and Fayette counties. Gibson received the assistance of Outdoor Recreation Planner Paul Labovitz, a Midwest Regional Office employee duty-stationed at Cuyahoga Valley National Recreation Area. In September 1990, the not-for-profit citizens group incorporated under Ohio law as "Tri-County Triangle Trail, Inc." The following year with the benefit of public input the group announced plans for a fifty-two-mile recreational trail along abandoned railway lines linking Chillicothe, Frankfort, Greenfield, and Washington Courthouse. As press attention escalated so, too, did grassroots membership and increased public involvement. [48]

Bill Gibson also laid the groundwork to form a "Friends of Mound City Group" by hosting a formation meeting on January 25, 1990. Like Ken Apschnikat's previous effort involving American Indians, initial enthusiasm did not result in perpetuating a park friends group. [49]

Gibson continued the community involvement of his predecessors. In 1990, he accepted an invitation from the Archaeological Conservancy to serve on its Ohio Advisory Committee. Using his position on a regional waste management advisory board, Gibson spurred recycling efforts at Mound City Group National Monument and received high visitor participation rates as well as favorable comments. He also became a founding charter member of the Federal Executive Association of Southeast Ohio, a body formed to further interagency cooperation and coordination. [50]

An initiative that began with a phone call to Omaha in 1989 eventually lead to substantial involvement by the state coordinator, introduction of legislation, and authorization of a new unit of the national park system. In the spring of 1989, Gerald Sharkey, president of Aviation Trail, Inc., in Dayton called Midwest Regional Director Don Castleberry to explain his group's efforts at preserving remnants of historic properties related to native sons Wilbur and Orville Wright. In response to Sharkey's request for a National Park Service assessment of the Wright-associated properties, Castleberry dispatched Historian Ron Cockrell to Dayton. Cockrell met with Sharkey and local historian Mary Ann Johnson, and inspected the wide range of properties on May 1 and 2, 1989. Impressed by what he saw, Cockrell recommended a national historic landmark survey be conducted along with preparation of individual nominations. The work took place during the summer of 1989, led by Regional Historian Jill York O'Bright, Historian David Richardson, and Historical Architect Bill Harlow. Seven nominations were prepared and considered for national historic landmark status.

Concurrent with the Omaha-led effort, Bill Gibson became involved and began serving on Dayton's 2003 Fund Committee, a group assisting Aviation Trail but focusing on celebrating the centennial of flight on December 17, 2003. From Mound City Group, Gibson helped coordinate a management alternatives study conducted by the Denver Service Center. The study, financed by private funds through the 2003 Fund Committee, came as a result of a request by Congressman Tony P. Hall of Dayton. Completed in early 1991, the National Park Service urged authorization of an affiliated area with limited federal funds and technical assistance but managed by local or state interests. Nonetheless, the Ohio congressional delegation introduced draft legislation calling for establishment of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park. In 1992, congressional hearings and political machinations led to passage and presidential approval for the new park. [51]

In a replay of the same circumstances which saw Bill Birdsell leave Chillicothe for a newly-established park assignment in 1975, Bill Gibson, rewarded for his hard work as state coordinator and the Midwest Regional Office's Dayton keyman, in April 1993 became the first superintendent of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park. [52]

Over the course of six decades, National Park Service willingness to acknowledge and appreciate public interest in its management of Mound City Group National Monument, and now Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, changed dramatically since Clyde King's superintendency. Through the late 1940s and 1950s, King operated at will, issuing press releases that usually were printed verbatim whenever King wished to announce what he deemed to be newsworthy events. His failure fully to communicate MISSION 66 policy and facility development with the community guaranteed the unpleasant, but predictable, public backlash. King realized his public relations blunder only when it was too late, and his superintendency ended under an unfortunate cloud. Subsequent managers learned from King's mistake, and did well performing their jobs inclusively and in concert with the community and area agencies. When public input into federal planning efforts became law under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, park managers received training in how to conduct public information meetings and incorporate that input in agency planning efforts. The special skill became a key job requirement. At Mound City Group, superintendents increased their effectiveness and simultaneously enhanced the park's visibility and profile by participating in community organizations. Contemporary managers, Ken Apschnikat, William Gibson, and Johnny Neal, have excelled in soliciting, evaluating, and implementing public concerns.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hocu/adhi/cha5.htm

Last Updated: 04-Dec-2000