|

Hopewell Culture

Amidst Ancient Monuments The Administrative History of Mound City Group National Monument / Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio |

|

CHAPTER SIX

Exhibiting the Hopewell Culture

Apart from the earthworks, objects retrieved by archeological investigations are the principal physical remnants of the Hopewell culture and serve as important means of teaching the public about the prehistoric past. Much human effort and financial resources have been expended to obtain, procure, and preserve Hopewellian artifacts. For the Squier and Davis collection lost to Great Britain during the Civil War, efforts to return it to the United States have waxed and waned since its purchase by William Blackmore. While a loan of some of the objects did occur, collective American hopes for the collection's repatriation have dimmed considerably at the end of the twentieth century.

|

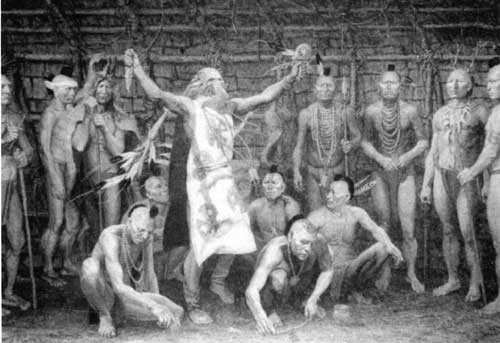

| Figure 53: Museum exhibit showing artistic interpretation of Hopewellian burial ceremony. Mural painting by Louis Glanzman. (NPS/ca. 1970s) |

Attempts to Retrieve Squier and Davis' Collection

The earliest public information describing the array of artifacts excavated by E. G. Squier and E. H. Davis from the Mound City Group in 1846 came in the form of a scholarly 1848 publication initiating the "Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge" series called Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. While the narrative did not fully detail the extent of the Mound City Group collection, it did indicate that the Hopewellian artifacts were numerous and of great detail and scientific interest to the nascent field of archeology. Edwin H. Davis ended up with the bulk of the artifacts following his professional split from Ephraim Squier, and Davis continued high-profile activities in prehistoric antiquities.

Unsuccessful in his efforts to sell the 1300-piece Mound City Group collection to the Smithsonian Institution or the New York Historical Society, Davis prepared a catalog featuring his cumulative collections and placed them up for sale on the open market. The catalog included not only Ohio antiquities, but those from his excavations in Peru, Central America, and Denmark as well. Davis preferred having the collection remain in the United States, but no American institution came forward to make a serious monetary offer.

In 1864, Davis sold the antiquities for $10,000 to William Blackmore, founder of the Blackmore Museum in Salisbury, England. In 1931, the Mound City Group or "Davis" collection changed hands again, sold to the British Museum, while the Peruvian and Central American artifacts went to Cambridge University and the Denmark specimens remained at the Salisbury-South Wiltshire Museum (formerly the Blackmore Museum). [1]

Both Henry C. Shetrone and Erwin C. Zepp of the Ohio Historical Society viewed the artifacts in England, with Shetrone obtaining several casts of effigy pipes in the late 1930s. University of Michigan scholar James B. Griffin studied the collection in 1954, but his observations were never published. With development of the Mound City Group National Monument during the National Park Service's MISSION 66 program, the agency expressed its own desire to study the Davis collection, and to compare it with artifacts unearthed in annual excavations beginning in 1963.

A partner in those excavations, the Ohio Historical Society in 1965 sent Curator of Archeology Raymond Baby and staff archeologist Martha Potter to the British Museum where they spent twenty days studying the Mound City Group collection, meticulously measuring and drawing each artifact. Less than two dozen effigy pipes were actually on public display while the other cache of pipes were wrapped in their seven original cloth bags stored in ten wooden boxes in a locked basement room. They discovered fragments comprising two pots, and assorted other artifacts with their accompanying provenance data. Baby and Potter were able to determine that the 1847 account only partially described the collection's actual extent. [2]

In 1958, Regional Archeologist John L. Cotter recommended the National Park Service actively pursue seeking the return of the Mound City Group collection from the British Museum. Cotter believed the agency had a "good chance" working through the secretary of the Interior and the Department of State to obtain the artifacts. Cotter did not mention the terms, be it goodwill or financial recompense, to negotiate for such a "return." Because the museum complex had been dropped from the MISSION 66 program at the time of Cotter's recommendation, the agency took no official action. [3]

In 1959, the Dayton Art Institute sought a "temporary return" of the prehistoric art pieces. On July 7, 1959, Institute Director Thomas C. Colt requested the assistance of Secretary of State Christian W. Herter to expedite the loan request for a special exhibit planned on the Hopewell and Adena cultures. The Eisenhower administration apparently did not take substantive action on the Dayton request. [4]

The 1965 England trip of Raymond Baby and Martha Potter sparked a renewed interest in seeking the return of the Squier and Davis collection. Baby reported that most of the items were uncleaned and unrestored. He found three provenance ledgers and the 1864 sale memorandum of agreement on file at the Salisbury facility. While in England, Baby understood from Adrian Digby, British Museum Head Keeper of the Ethnographic Section, that a six-month loan could be arranged. Surprisingly, British Museum officials denied Baby's formal request to clean, record, photograph, and display the materials at the Ohio State Museum. The news prompted Acting Mid-Atlantic Regional Director George A. Palmer to request help from the Washington Office, stating,

Due to the fact that there are only a few artifacts from the several pre-National Park Service excavations at Mound City Group presently on display or otherwise available at the area, we suggest that the Service make a definite effort to initiate formal action presumably through the State Department, to obtain the Squire [sic] and Davis artifacts from Mound City for the National Park Service, preferably as a permanent acquisition for study and display purposes. Such an acquisition, we believe, is more than warranted by the historical importance, as well as the scientific significance of the Squire [sic] and Davis collection. [5]

Headquarters officials focused their hopes on the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution, and its interest in the collection because of volume one of the "Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge" series. During the summer of 1966, Smithsonian employees visited London and during the course of their work, urged British Museum officials to enter into a loan agreement along the lines proposed by Raymond Baby. The Smithsonian's effort appeared to be only half-hearted as Anthropologist Richard B. Woodbury explained in early 1967:

I have explored at considerable length the possibility of the Smithsonian attempting to arrange a loan from the British Museum of the Hopewell pipe fragments that Ray Baby examined when he was there. The reaction I have from all sides is extremely negative. This is based on the principle that it is risky for the Smithsonian to become a third party in research activities that do not directly involve the work of one of its staff members. In this case we would have to undertake full responsibility for any work done with the Hopewell material, yet it would be only feasible for it to be done by Baby in Columbus rather than here. Our unwillingness to become involved does not stem from any lack of confidence in Baby or lack of interest in the research he contemplates with the material.

Woodbury told the National Park Service that Baby should pursue a grant to visit the British Museum and perform the study in England. [6] Chief Archeologist John M. Corbett, in conveying the bad news, admitted, "for the time being there does not seem to be much hope for getting the material back." [7]

The matter languished until General Superintendent Bill Birdsell revived it in 1973. A visit to Chillicothe by International Affairs Specialist Fred M. Packard initiated the concept of swapping other artifacts for the Mound City Group collection. Packard related an inquiry from the British Museum seeking American Southwest materials possessed by the National Park Service. Packard learned from Chief Curator Harold L. Peterson that headquarters officials were planning on asking the British Museum for their cooperation in making reproductions of their Mound City Group holdings. With the rise of American Indian cultural and political activism, however, Peterson added the following, "My only mental reservations about the display of the original objects at Mound City lie in the uncertainty the more militant members of the American Indian Movement might take towards such an exhibit. As you know, there have been some fairly strong statements about the propriety of displaying objects of religious significance or objects related to burials. To the best of my knowledge, none of this has really crystalized into a policy as yet, but there is just a possibility that these very valuable objects might be safer in England than they would be here." [8]

Hopes for a permanent swap with the British Museum per Packard's suggestion dimmed in late 1973 when Chief Historian Harry W. Pfanz opined that the Antiquities Act of 1906 prohibited the sale or trade of cultural resources obtained from federal lands. Non-federally obtained objects from private collections could still be arranged for a trade, but even the legality of that proved problemmatic. Any exchange would have to be made on a negotiated loan basis, and no formal request from the National Park Service had yet been submitted to the British Museum. [9] A few weeks later, Packard appealed to John Cripps, chairman of the Countryside Commission for England and Wales, about a loan or reproduction of British-held Mound City Group artifacts. Encouraged in learning about the renewed effort, Raymond Baby again offered the services of the Ohio Historical Society, noting that Mound City Group National Monument lacked the facilities and staff to perform the cleaning and restoration work. Baby offered to go to London at his own expense to assist in packing the artifacts for shipment. Unfortunately, news from England proved yet again negative. [10]

Fred J. Fagergren tried again in 1976. Fagergren set a personal goal of trying to arrange a return of the artifacts as part of the nation's bicentennial celebration. This effort he directed through the National Park Service's Harpers Ferry Center, the agency's central organ for museum and interpretive programs. Fagergren urged coordination again through the Washington Office's division of international affairs and to emphasize the British Museum's desire for Southwestern materials. He also recommended joining forces with the Ohio Historical Society, which had its own loan effort underway. [11]

Harpers Ferry Center Manager Marc Sagan requested National Park Service Director Gary E. Everhardt contact the new director of the British Museum, Sir John Pope-Hennessy. Sagan affirmed "It would be nice to have the whole collection, but we do not need it. In fact, if we obtained it, some would probably have to be stored in the Ohio Historical Society. If we could obtain a few representative pieces, they should be sufficient for exhibit purposes. Failing that, good casts of the originals would be a help." [12]

In mid-May 1976, the National Park Service made its first direct, high-level appeal for the Davis collection. The text of Acting Director Raymond L. Freeman's letter follows:

A century ago The British Museum showed the perspicacity to acquire the collection of Hopewell Culture artifacts excavated in Ohio by Squier and Davis. This was at a time when no institution in this country either recognized their significance or had the funds to obtain them.

The National Park Service is now designing a museum to interpret the site where these objects were found, and we wonder if it would be possible to work out an exchange for some of these artifacts or, failing that, to obtain reproductions of them. Some years ago, just before you became Director of The British Museum, we explored this possibility with some of the staff, and they indicated an interest in acquiring some artifacts from the Indian cultures of the American Southwest. We might be able to offer some such artifacts now if such an exchange is still of interest to you.

We would like to assure you that we do not subscribe to the current popular attitude that such artifacts ought by right to be returned to the place of their origin. After all, if it were not for the foresight of The British Museum and of some Continental European museums, these objects would have been lost completely. The same is true of Classical and Near Eastern antiquities. Younger nations owe such great institutions a debt of gratitude for saving these objects. At the same time, however, we hope that you can appreciate the difficulty we face in interpreting a culture with no important artifacts whatsoever. It is because of this that we herewith broach the possible exchange, or of obtaining some casts from the originals. [13]

The response from England came in the form of a verbal exchange between the British Museum director and Harold Peterson of Everhardt's staff. Sir John Pope-Hennessy cited the British Museums Act of 1963 and subsequent British law for preventing the trade or return of artifacts. Underlying the director's concern was the fear that if one collection is returned or exchanged to its country of origin, other nations would then clamor for analogous deals. The Englishman did agree to have high quality reproductions made. [14]

Fagregren refused to accept the undocumented "no" for an answer. In September 1979, he asked Regional Director Jimmie L. Dunning for approval to reopen formal discussions "to investigate the possibility of a permanent exchange of artifacts, or an exchange based upon long-term loans." Fagregren urged the Washington Office's international affairs office to work through the State Department to secure the indefinite loans or exchanges. Fagergren asserted that recent American visitors to the British Museum reported seeing few if any Mound City Group artifacts. Some pieces did emerge every few years as part of a rotating display, but much of the collection remained in storage. [15]

The Midwest Regional Office concurred with Fagregren's position that the matter deserved to be elevated to government-to-government negotiation, but saw "very little hope for our ultimate success." The Omaha office believed that British law had not changed in regard to repatriating antiquities, and pointed out that neither the United States nor Great Britain had ratified the UNESCO convention in 1970 dealing with return of archeological materials. In the hope that different attitudes might prevail in light of new management of the British Museum, the request to re-open the issue went forward to the Washington Office. [16]

Washington officials decided against elevating the negotiation to the State Department, and instead Deputy Director Ira J. Hutchison directly requested a loan of the Davis collection in November 1979. Keeper of the British Museum's Ethnography Department M. D. McLeod immediately asked for "more detailed information about which items you wish to borrow, where these are to be exhibited, under what security and conservation conditions and for what length of time." Awaiting the receipt of such information in order to process the request, McLeod sent a copy of the museum's loan regulations and stated that all requests had to be approved by the board of trustees. [17]

Fagergren responded to McLeod's questions in general, and to his superiors expressed disappointment that a loan, rather than acquisition, was the only avenue being pursued. Fagergren's frustration also produced a letter from park files suggesting that some of the collection may have been lost or stolen, and that the museum could only have replicas. The issue seemed to contradict the professional findings of Raymond Baby and Martha Potter who viewed and studied the collection in 1965. On the surface, it appeared to be sour grapes on behalf of Fagergren, and introduction of the issue only served to cloud the difficult matter even further. [18]

Press coverage of the attempt to secure a long-term loan in mid-1980 revealed Fagergren's optimism that a deal could be struck with the British Museum. Fagergren expressed the belief that the collection could return to Mound City Group National Monument "for a few months," although he would like to have it for scientific study for five to ten years. British Museum officials were querying Fagergren on the monument's security and environmental conditions for the Davis collection. Press reports also revealed that the Ohio Historical Society's two attempts to secure a loan had both failed. [19]

British Museum curators determined the Mound City Group National Monument facilities did not pass muster, and rejected Fagergren's loan application. In late September 1982, Midwest Regional Curator John E. Hunter ventured to London to examine the Davis collection and discuss the potential loan directly. [20]

National Park Service efforts to obtain a loan failed, but the Ohio Historical Society succeeded in 1986 when 26 items were delivered in Columbus by British Museum Curator for North American Collections Jonathan King. Martha Potter Otto changed tactics in the spring of 1983 and asked for a one-year loan of a select portion of the Davis collection to be displayed in a new prehistoric Indian exhibit. It represented the first time since E. H. Davis moved to New York in 1850 that the Hopewellian artifacts had returned to Ohio. Otto affirmed that the society had not forsaken its aim of recovering the entire collection, stating, "That's always something we have in the back of our minds." [21]

Prior to the exhibit opening, Dr. Mark J. Lynott, Midwest regional archeologist, accompanied James Brown, professor of anthropology at Northwestern University, to conduct a comparative study of Mound City Group artifacts with Davis collection pieces. Brown was under contract with the National Park Service to evaluate all Mound City Group-originated artifacts. Part of Brown's work uncovered correspondence and tracings in the E. H. Davis papers collection at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts. Brown obtained the materials on microfilm, and recommended professional reproduction of the sketches of never-before-seen illustrations.

Most importantly, Brown found a large-scale map of the Mound City Group earthworks, including a section excluded from the 1847-published map. Another sketch showed the central three mounds standing in an open woodlot, demonstrating the vegetation that existed prior to cultivation. A third tracing depicted two pot rim sherds used in 1847 to recreate two pots for the subsequent Smithsonian publication. It suggested that upon excavation in 1846, none of the Mound City Group pots were discovered whole. [22]

While NPS has failed to secure the return of any British-held Mound City Group artifacts, the position of the foreign museum and government finally became known. As long as federal museum facilities in Chillicothe remain substandard, even a loan of these unique artifacts cannot occur.

Ohio and the 1920-21 Mound City Group Collection

During the first two decades of National Park Service administration of Mound City Group National Monument, the agency remained content to have the 1920-21 artifacts excavated by the Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Society from the Chillicothe monument remain in the Columbus society's possession and care. As Superintendent Clyde King wrote in 1957, "The entire Mound City collection is now at Ohio State Museum where all but a few of the 10,000 artifacts are in storage. Except for a limited number of display objects [here], it is appropriate that the bulk of the Mound City Group collection be retained for study purposes at Ohio State Museum." [23]

As the monument underwent development and the visitor center and museum complex began operating, the National Park Service's attitude on this topic underwent a fundamental transformation. A management study prepared by the George A. Palmer of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Office in 1968 noted the on-going contractual relationship whereby artifacts excavated from Mound City Group in the 1960s were cleaned and provenanced by Ohio Historical Society staff, professional reports prepared, and the items returned to the National Park Service for cataloging. Palmer's report acknowledged a "gnawing administrative problem" dating to 1946, concerning the artifacts excavated by the Ohio Historical Society in 1920-21. The Ross County Historical Society, ever mindful of the loss of the Squier and Davis collection, resented removal of those artifacts to Columbus and continued to dispute the proprietorship and display of the 1920-21 items. Palmer cited the 1946 letter from the Department of War ruling that the excavated material remained federal property, a finding not officially shared with the historical society. Before the agency made any attempt to reclaim the collection, Palmer declared the National Park Service "must determine if we can preserve them as well as Ohio Historical Society and if recovered would they be retained at Mound City or Ocmulgee [Southeast] Archeological Center." To remove them from Columbus would engender "strained relations" as would moving them outside Ohio create difficulties with local citizens. [24]

In response to Palmer's management report, John Cotter, chief of archeological research at the Philadelphia Planning and Service Center, recommended retrieving the 1920-21 artifacts. Cotter declared,

The National Park Service is the one and only legitimate owner and caretaker of the remarkable Mound City Group archeological collection housed at Ohio State Museum. By continuing to neglect its right and duty to establish ownership and curatorship of these artifacts, the Service is prolonging a dereliction which it cannot justify except on the premise that Ohio State Museum and the Ohio Historical Society represent responsible and competent scientific agencies and that the new Ohio State Museum building now under construction may provide admirable facilities for display[. This] does not establish legal ownership of the artifacts or prevent the Service from providing adequate display and safety for them at Mound City Group. [25]

No follow up on the issue occurred during the late 1960s. The next decade saw not only two changes in superintendents, but the regional boundary shift brought new central office managers in Omaha completely oblivious of the issue. The changes resulted in a quick loss of the proverbial "institutional memory" because agency managers literally forgot about the legal basis upon which they asserted ownership of the 1920-21 artifacts.

|

| Figure 54: Copper hands were but some of an assortment of Hopewellian artifacts on display in the visitor center's small museum. (NPS/July 1981) |

The ownership question rekindled in 1976 as a fundamental reworking of the visitor center exhibits by Harpers Ferry Center included some of the 1920-21 artifacts, some of which were on display in Columbus. In response to a meeting with Fred J. Fagergren and F. A. Calabrese, chief of the Midwest Archeological Center, during which the new exhibit requirements were discussed, Martha Potter Otto wrote, "we need to consider carefully the items requested from our collections that were recovered by Mills and Shetrone. Certain artifacts can probably be loaned without any problem, however, items such as the duck pot that are a critical part of our exhibits may be a more difficult matter." [26]

The dispute centered around eight one-of-a-kind artifacts the Columbus-based society had on public display. It understandably did not wish to relinquish them to Mound City Group National Monument. After consulting advisors in Omaha and Lincoln, Fagergren sent an August 1976 letter officially requesting the return of the items prior to their installation in the new exhibits, projected to begin on October 1. While not directly addressing the issue of ownership, Fagergren's presentation suggested just that. He expressed the hope that the society had adequate time to produce replicas, thanked it for storing and caring for the items, and requested notification of a mutually satisfactory transfer date. [27]

Stunned Columbus officials did not immediately respond to Fagergren's request nor did they wish to discuss relinquishing the disputed artifacts. The October 1 deadline came and went with no resolution of the matter in sight. A late February 1977 search of the park's "dead files" brought about the rediscovery of the April 19, 1946, letter from Secretary of War Robert P. Patterson to Interior Secretary Oscar L. Chapman addressing the issue of federal ownership of the 1920-21 excavated items. Fagergren quickly presented the society with the letter and Columbus officials, not wishing to engage in a potentially nasty public battle, particularly with vocal and influential Chillicotheans, agreed to the proposed transfer of requested items to Harpers Ferry Center for installation in the new exhibits. [28]

Concerning items not on display, it soon became clear that inadequate recordkeeping created the illusion of duplicate artifacts. The confusion cleared when curators determined that items documented as in storage at Columbus had in fact been delivered to Mound City Group National Monument in previous years. It resulted in a detailed study of all Mound City Group artifacts, both at the monument and in Ohio's capital city.

The evaluation brought about an onsite inspection of Ohio Historical Society curatorial storage areas. What Superintendent Fagergren saw shocked and disabused him of the preconceived notion that the Columbus facilities were superior to the national monument's. Such was not the case. He reported that "Most of the copper artifacts have been severely damaged by oxidation and 'copper disease.'" He notified the Midwest Regional Office of his intention to transfer the entire 1920-21 collection to the monument as soon as possible. He asked that a professional assessment be conducted of the artifacts to determine which specimens needed immediate preservation treatment by Harpers Ferry Center prior to their return to Chillicothe. In requesting all deliberate speed, Fagergren grimly concluded, "I am afraid that much of a once-very-valuable collection has been severely damaged through neglect and improper care." [29]

Midwest Regional Curator John Hunter arrived in Columbus in late October 1977, and with park staff assistance from Bonnie Meyer [Murray], made an assessment of the condition of Mound City Group artifacts. Hunter concurred in Fagergren's decision not to leave the collection at the Ohio Historical Society. On November 1, 1978, Fagergren presented Martha Potter Otto with a list of all artifacts believed to be in the society's possession and asked that they be brought to one location for delivery by January 15, 1979. National Park Service staff accomplished wrapping and packaging the materials on January 17, and much of 1979 was devoted to cataloging, storing, and arranging for preservation treatment by Harpers Ferry Center. A preliminary inventory indicated missing items believed to be still in Columbus. [30]

The extent of the missing items became clear in early 1980 when park curators opened the last cabinet of artifacts. Following the long process of inventorying the artifacts, Fagergren contacted Martha Porter Otto and sent a list, noting that some artifacts remained on display and needed to be picked up. While the society again searched its holdings and failed to produce the items, it was not until James A. Brown's inventory conducted under contract in the early 1980s that a clear picture emerged. In 1983, Brown informed the Midwest Archeological Center that "quite a few items Mills reported were never accessioned by the Ohio State Museum. There are some big gaps in the collection the NPS has of the 1920s dig." [31]

By the end of the 1970s, most of the Mound City Group artifacts from the 1920-21 excavations had been returned to Chillicothe. While local citizens and supporters cheered the transfer, most remained unaware of the condition and extent of the collection. For the first time, Mound City Group National Monument found itself in charge of a substantial array of primary site-originated artifacts, but struggled to determine its exact parameters and preservation needs.

Mound City Group Visitor Center

Mound City Group's MISSION 66 visitor center opened in 1960 as a simple one-story brick and stone veneer building of 3,100 square feet. The museum component represented an enclosed L-shaped corridor containing exhibits attached to a fieldstone wall with the other wall comprised of large glass windows affording visitors simultaneous viewing of exhibits and the exterior mound area while passing through the museum. Unfortunately, the designer was only told the structure was for "an Indian area," and not specifically for the sometimes harsh weather extremes of Ohio. The designer, thinking of the more moderate Southwest, intended the museum to be open-air and subsequently changed the outer L-shaped walls around the inner patio to consist of single-paned glass. The hastily prepared, ill-advised design placed the building's principal air circulation outlets in the museum area and featured circular, roof-mounted air ducts with deflectors. The configuration proved woefully energy-inefficient and could not provide a stable environment for the artifacts. [32]

|

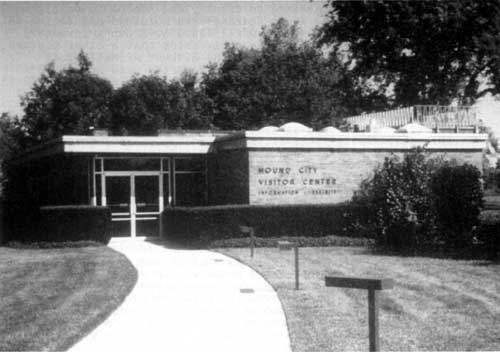

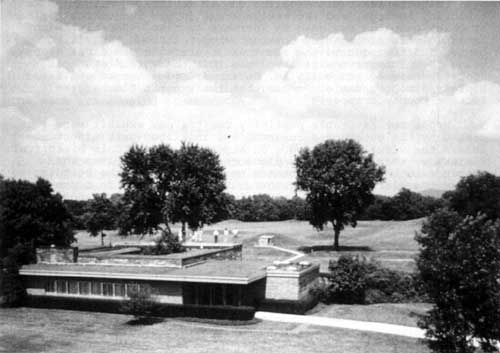

| Figure 55: The 1961 MISSION 66 visitor center proved inadequate to National Park Service interpretive and curatorial needs. (NPS/Bonnie Murray, October 1980) |

The extensive excavations of 1963 and 1964 made the 1960 exhibits obsolete and prompted calls for their revision and replacement. Suggestions for changing the "Shrine Ceremony" and "Cremating the Dead" exhibits came in 1965 to reflect the new archeologically-produced knowledge. [33] Monument staff also were concerned about making the exhibits more appealing by adding new artifacts and interpretive data. They emphasized eliminating the monotonous two-dimensional characteristics of the displays by adding angles and elevated surfaces to the cases.

In October 1965, Superintendent James W. Coleman, Jr., called for replacement of all Mound City Group exhibits. He reported problems with peeling paint and faded colors in addition to outdated information. On October 7, Washington Office Curator Vera B. Craig examined the park's museum operations and concurred in an "overall revamping" of exhibits. She also attributed the increasingly apparent deteroriation and fading problem to the intensity of ultraviolet light passing through the glass walls. As a stopgap measure, Craig recommended installing light-colored sheer curtains on traverse rods so as to be easily opened and closed for operating hours. In addition to the fading and blotchy coloring of exhibit panels, she noted fluctuating humidity conditions were contributing to "flaking" of painted surfaces. [34]

Rehabilitation work on three exhibits commenced in May 1967. Prior to their shipment to the Eastern Museum Laboratory in Washington, D.C., the panels were photographed and the prints were enlarged for temporary visitor use. Six separate exhibit case revisions underwent review in 1967, and brought about a decision to include the issue in a parkwide interpretive prospectus exercise. In the meantime, exhibit case reflection and deterioration problems grew worse. [35] In 1969, Superintendent George Schesventer considered removing the two exhibits, "Why Did They Leave?" and "Other Outstanding Mounds" because of extreme deterioration. In the former, he commented on use of a bow and arrow to depict enemies as a "glaring error." Schesventer declared, "It is an anachronism inasmuch as the bow and arrow was not in use then. Having it associated with the Hopewell Culture would be like portraying the Minutemen using machine guns at Lexington and Concord. The proper weapon to be shown in use in this panel should be either a spear or an atlatl and dart." [36]

A 1971 proposal to install smokey gray plexiglas panels to reduce the exhibit glare and deterioration problem was ultimately rejected by Harpers Ferry Center because of unacceptable adverse visual and esthetics concerns. [37]

Ongoing planning to upgrade exhibits in 1972 yielded an interpretive painting for the burial exhibit "Cremating the Dead" by an Ohio Historical Society museum artist in close consultation with Martha Potter Otto. Birdsell, wishing to "avoid undue provocation in these sensitive times" and no doubt recalling the occupation of National Park Service-operated Alcatraz Island by American Indian Movement members, decided to remove the few human bones included in the exhibit design plan. In early 1973, Harpers Ferry Center exhibit specialists Ike Ingram and Ben Miller visited and commenced planning and designing new Mound City Group exhibits. In the interim, Birdsell decided to purchase diaphanous draperies for the museum area in hopes of retarding ultraviolet light damage. [38]

Again the National Park Service's reorganization of 1973-1974 intervened to skew Mound City Group National Monument planning efforts. The exhibit concept plans completed in September 1973 remained in limbo until mid-1975 when Harpers Ferry Center queried Omaha officials about it. A search of the transferred Philadelphia files revealed nothing about the planning document. A turnover in Chillicothe park staff also contributed to the delay. An expedited review, however, yielded dissatisfaction with the product and the Midwest Regional Office organized a spring conference with park and Harpers Ferry Center staff to discuss it. The consensus of 1973 had clearly evaporated with substantial changes in content and design proposed. Of particular concern was the "extent to which the plan deals with the funerary and mound building aspects of the Hopewellian culture." Midwest Regional Chief Interpreter Jim Schaack negotiated a redesign of the lobby, inclusion of a security system, reconsideration of exhibit 12 dealing with cremated remains, and revisions to exhibits 15 and 18 to include nonfunerary aspects. [39]

|

| Figure 56: A conceptual model of a Hopewell house appeared in the visitor center prior to a 1978 comprehensive exhibit redesign. (NPS/Richard Frear, April 1972) |

Funding for the new exhibits, anticipated during the interim period between fiscal years 1976 and 1977, [40] evaporated due to a "clerical error" at Harpers Ferry Center. An upset Fred J. Fagergren denounced the communications gap and asked for priority consideration in the Midwest Region's fiscal 1978 exhibitry requests over Agate Fossil Beds National Monument, Nebraska, and Effigy Mounds National Monument, Iowa. In the meantime, Mound City Group staff scrambled to assemble temporary rotating exhibits to augment the static, deteriorating displays covering secondary subjects like historic canals, wildflowers, archeological methods, and birds. [41]

In 1977, museum rehabilitation included lobby installation of a central visitor information and sales desk, a sales rack, temporary exhibit case, and an introductory interpretive panel, all paid by Eastern National Park and Monument Association funds. Fagergren, spurred to action by a 1976 burglary, began working with the regional office to design a security system, something that proved problemmatic in the absence of designs for the new exhibits. Installation of those exhibits came in July 1978, with work finally completed in early 1979. The rehabilitation work met with universally positive public acclaim. Work on an eight-minute interpretive video "The Hopewell Indians" concluded in February 1979, thus ending a decade-long effort to upgrade the museum exhibits. [42]

|

| Figure 57: Glare from the glass-wall separating the museum and courtyard proved not only annoying for visitors, but ultraviolet rays damaged sensitive prehistoric objects. (NPS/ca. late 1960s) |

The monument addressed the long-fought problem with glare, fading, and fluctuating temperature and humidity caused by the glass-paned walls in 1981 by converting to a thermopane system. Dual panes and seals were installed on the thirty-six windows covering 636 square feet. Problems with moisture being retained between the glass resulted in the contractor honoring its guarantee and replacing more than three-quarters of the panes the following year. Water intrusion through the flat metal roof, an ongoing problem, stained a museum mural in 1982, resulting in the mural's replacement in 1983 by Harpers Ferry Center. A groundwater heat pump system installed in 1982 brought numerous operational problems and uncomfortable conditions leading to three prolonged closures exacerbated by spotty service, improper installation, and warranty problems. Replacement of the visitor center observation deck in early 1983 included placement of heated mats to thaw ice and snow as well as benches for sitting, thereby enhancing visitor safety and comfort. [43]

An overflow parking lot using "turfstone" on a stabilized turf area came in 1981 and provided expanded capacity whenever needed during peak visitation periods or special events. Workers also constructed handicapped parking spaces and walkway accesses for the visitor center lot. [44]

Moving an exhibit case in August 1986 to allow an archeologist to study some earspools resulted in the unfortunate breaking of two copper artifacts. Two Harpers Ferry Center exhibit specialists made an emergency trip to rehabilitate the jostled exhibit, and the two copper pieces, a human torso headdress and a falcon, were taken back to West Viriginia, repaired, and replaced in April 1987. [45]

Another attempted break-in during April 1988 saw a brick hurled through the window of the audiovisual room to gain access. Sounding of the security alarms frightened off the intruder. Five days later, another forced entry proved unsuccessful yielding severed wiring to a roof-mounted siren and abortive prying on an enclosure containing another siren. Ken Apschnikat, noting newspaper advertisements offering substantial monetary payments for artifacts and recent looting and burglarizing at a state-operated site, acted immediately to ensure heightened security at Mound City Group. [46]

Weary of reacting to perennial leaking of the flat visitor center roof and enduring water damage to interior museum and office areas, a reroofing project in 1992 included a visually dramatic solution to the problem. A metal pitched roof installed in the spring of 1992 not only easily drained away precipitation, but altered the appearance of the nondescript MISSION 66 structure, particularly with the metal's shiny bright-red coloring which complimented the existing brick. [47]

With the transformation into Hopewell Culture National Historical Park came remodeling and redesign of the inadequate visitor center. At long last, an auditorium accommodating fifty people permitted viewing of an award-winning orientation film. Expanded exhibit and sales areas also improved visitor enjoyment. The 1997 general management plan calls for additional construction to provide additional space for the educational and curatorial demands of a growing park. The 1997 general management plan recognized the need to provide a comprehensive interpretation of Hopewellian life, less focused on mortuary behavior. The vintage 1978 exhibits were designed prior to the first modern synthesis of Hopewell archeology the following year. The deficient exhibits were designed poorly with respect to artifact safety as well.

Exterior Exhibits

Following construction of the visitor center museum building in 1960, it soon became apparent that visitors required interpretive signage in the outdoor areas of significant cultural and natural resource interest. The April 1963 installation of "The Mound City Necropolis" wayside exhibit immediately attracted visitor attention and appreciation. Placed just inside the entrance to the west wall of the mound enclosure, it helped orient visitors to the prehistoric topography surrounding them. [48]

|

| Figure 58: A button-activated audio program assisted visitor understanding while surveying Mound City Group on the visitor center observation deck. (NPS/Sprague Photography, ca. 1965) |

|

| Figure 59: "The Mound City Necropolis" wayside exhibit. (NPS/Sprague Photography, ca. 1965) |

An interpretive audio program atop the observation deck during after-hours saw its first use in August 1965. In its first weeks of service, park employees noticed that its principal usage came in the early morning hours instead of in the late evening as anticipated. Upgrading audio messages to meet sound and quality standards came in 1973 through the efforts of Mound City Group Interpretive Specialist Robert F. Holmes working with the Harpers Ferry Center. [49]

A sign plan contained within an intepretive prospectus completed in the mid-1970s determined that the self-guided trail mapped out in the park's brochure was not adequate in interpreting key features to visitors. With the necropolis wayside moved outside the mound enclosure closer to the visitor center, the only other sign depicting the charnel house outdoor exhibit was temporary and did not meet standards. In 1976, six cast aluminum panels were developed: "Mound of the Pipes," "Death Mask Mound," "Scioto River," "Camp Sherman," "Charnal House Exhibit," and "Ohio & Erie Canal Stone." All six were installed in April 1977, and the mound area signs were placed close to the ground, abutting the slope of individual mounds. Others were mounted to metal stanchions. Maintenance workers mounted the panel on the Scioto River trail atop a stone pedestal specially constructed for the purpose in 1975.

The signs dramatically improved the self-guided visitor experience in the mound area as well as Scioto River trail. Fifty small metal photographic and text signs were installed throughout the area identifying native plants and relating how American Indians and white settlers used them in their daily lives.

According to the interpretive prospectus, intentions for the charnal house exhibit included full-scale reconstruction of such a prehistoric structure on either Mound 10 or Mound 15. However, National Park Service policy regarding any reconstruction changed in the 1970s in response to criticism that past efforts contained inaccuracies or were blatantly false. Official policy included rigorous criteria which had to be met prior to funding a reconstruction. Because archeologists could only speculate as to the above grade configuration of a charnal house, plans for the reconstruction were cancelled in 1976. Instead, the charnal house pattern post molds were highlighted on the ground. In turn, this became a maintenance dilemma attracting weeds and debris. In response, in 1985 a local Boy Scouts of America troop spread sand in the charnal house exhibit area as well as in front of other interpretive wayside signs. [50]

|

| Figure 60: Charnel house exhibit. (NPS/ca. 1970s) |

|

| Figure 61: "Pipe Mound" wayside exhibit. (NPS/ca. 1970s) |

By far the most visible exhibit within the Mound City Group enclosure was the mica grave at Mound 13. Begun in 1963 with Accelerated Public Works Program funding, the Ohio Historical Society designed and built the in-place exhibit as a component of its contractual partnership with the National Park Service to perform archeological excavations and restorations at Mound City Group National Monument. Archeologists chose Mound 13 for this intensive interpretive treatment because of the quality and quantity of its cultural resources. Its documentation by discoverer William C. Mills in 1920 proved to be another contributing factor in Mound 13's selection. The exhibit's purpose was to portray a group of Hopewell burials as they were discovered inside the prehistoric mound, including original cremated remains, four-by-six-inch mica sheets, replicas of copper head-dresses, and mica "mirrors" associated with two of the four burials.

Cy Webster of the Ohio Historical Society directed the mica grave construction, a concrete foundation with concrete block walls and a copper roof. The exhibit included a push button-activated audiotape recording, two ventilation fans, two florescent lights, and two floodlights. Construction work ended in October 1964, but because the exhibit window faced west, direct sunlight made the exhibit impossible to see. Substantial glare and reflection problems on the temporary glass panel necessitated a quick design change to incorporate a redwood baffle erected two feet in front of the exhibit. Accomplished the following month, the feature helped reduce the visibility problem and had the added attraction of identifying it for visitors by featuring "Mica Grave" in solid brass lettering accompanied by a Hopewell depiction of a falcon. Installation of permanent "Herculite" glass came on April 20, 1965, effectively completing the exhibit. [51]

|

| Figure 62: Construction of the Mica Grave exhibit. (NPS/October 1964) |

|

| Figure 63: The Mica Grave, directly behind the visitor center, attracted visitors inside the Mound City Group enclosure wall via a connecting concrete walkway. (NPS/early 1970s) |

Although the modern structure constituted an unmistakable intrusion on the prehistoric scene, its immediate popularity with visitors ameliorated those concerns. Despite its design flaws, the Ohio Historical Society expressed pride in the exhibit. On September 28, 1965, Ohio Governor James A. Rhodes visited Mound City Group National Monument with an entourage of twenty-five other dignitaries. His stop was one of several on a tour of historic, natural, and recreation areas in his "Wonderful World of Ohio" campaign designed to increase tourism. Superintendent James Coleman accompanied Governor Rhodes through the visitor center and then out to the mound enclosure with the first stop being the mica grave exhibit. Told that the Ohio Historical Society designed and built it, Governor Rhodes turned and told society director Daniel Porter that the exhibit "looks like a Jackson County crapper!" [52]

Hopes for favorable publicity for the new exhibit were dashed by the governor's remarks, and initiated park efforts to lessen the visual intrusion. On August 25, 1966, Ohio Historical Society workmen returned to place removable covers over the entrance to the exhibit, connecting the baffle to the building to reduce the glare problem further. Five days later in hopes of making it less intrusive, park maintenance painted the concrete blocks green. Coleman reported, "Everyone seems to agree that the appearance of the exhibit is much improved." [53]

In May 1979, severe deterioration in the form of leaking concrete walls and water accumulating within the mica grave exhibit threatened the burials and artifacts themselves. Within one week of reporting the emergency situation, the Midwest Regional Office provided funding and park maintenance workers removed the mound from around the building to expose its foundation and footings for cleaning, sealing, and installation of drain tiles. Taking advantage of the ground disturbance, park employees re-interred a partial skeleton previously donated to the monument. They subsequently restored Mound 13 to its correct configuration. [54]

Destruction of the redwood baffle in 1980 by vandals brought about its replacement with pine boards backed by plywood for added strength. By the late 1980s, the overall condition of the exhibit required rehabilitation to meet standards. Park maintenance treated the exterior in 1990, making it handicapped accessible, reduced glare, helped precipitation runoff, and replaced the sidewalk. In early 1991, Harpers Ferry Center via a contractor accomplished the interior exhibit rehabilitation. A freak lightning strike on May 18, 1991, damaged electrical outlets and melted wiring, but harmed nothing else. [55]

Until 1996, the mica grave was the most popular exterior exhibit at Mound City Group. With the previous removal of cremations, consultation with American Indians found the intrusive structure objectionable. NPS promptly removed all exhibit items and began planning alternative means of treating the mica grave using other media. [56]

Curatorial Services

As the National Park Service gained visibility and stature in the Chillicothe area, amateur archeologists began contacting Superintendent Clyde B. King with offers to donate parts or the entirety of their personal collections. The first offer came in September 1953 when Harold Steel presented King with his late father, Samuel Steel's, collection obtained from local mounds and farm fields. King accepted the relics for study, identification through State Archeologist Raymond S. Baby, and potential display. Those items of no association or use would be returned, with the remainder accessioned into the park's collection. The news brought about a swift response from the Richmond regional office clearly restating agency policy. While accepting prehistoric Ohio relics unrelated to the Hopewell for such plainly-identified exhibits was acceptable, Assistant Regional Director Daniel J. Tobin stated, "Only those objects which can definitely be identified and are suitable for future museum use or for study purposes should be accepted. If this is done they should be cataloged carefully so that there is no possible chance of their becoming associated with Mound City at a later date." Tobin warned that "If the specimens cannot be identified they should not be accepted. As a rule, unless the locality where a specimen was found, its association in situ, and the conditions of the findings are known exactly, it is usually worthless for exhibition or study." The result proved to be the acceptance of a scant twenty-five objects. [57]

Negotiations with other potential donors followed the same formula. A substantial Ross County collection donated to the monument came on June 29, 1964, with acceptance of the Biszantz collection. It numbered over one thousand pieces and included artifacts removed from the Hopewell Group and two surrounding farms. [58]

Park Archeologist Lee Hanson began the first inventory of Mound City Group's museum collections in April 1965. Hanson worked to process and store the material, estimated to be at 10,000 pieces, in the following three stages: 1). Inventory all previously cataloged material to determine condition and location; 2). Accession all remaining specimens; and 3). Catalog all accessioned material including cleaning and preservation work. The first two stages were completed within two months, and by the end of 1965, all specimens excluding materials from the 1963-65 excavations were cataloged. Because those items remained for study and reporting purposes at the Ohio Historical Society, they could not be processed. Hanson's cataloged collection stood at slightly over 4,000 pieces. [59]

Three years later, the total surpassed 10,000 specimens through continued donations, purchases, indefinite loans, and ongoing excavations. Artifacts from the Ohio Historical Society's early 1960s excavations began arriving for curation and storage space became stretched to the limit, with more excavations anticipated. Initially, museum storage cabinets occupied the small, increasingly cramped visitor center office. Master plan provisions called for curatorial storage and laboratory space in connection with expanded audiovisual areas, but funding to expand the visitor center was not forthcoming. Dr. John Cotter, chief of archeological research in the Philadelphia Planning and Service Center, proved to be the most vocal critic of Mound City Group facilities. Addressing the inadequacy of the structure for interpretive services, Cotter declared:

[It was] designed as a semi-enclosed walk-through panel display corridor with rest rooms and a tiny indoor lobby, plus small office space. As such, it has never functioned as a museum facility. This has been a continuing bitter disappointment to the Ross County and Chillicothe residents as well as to many visitors who learn of the remarkable collections secured in the archeological investigations of the 1920's and 1960's. The fact is, the Visitor Center is badly deficient as an interpretive facility which should measure up to modern NPS standards in general and the needs of this area in particular. There is no auditorium, no AV facilities, no storage space, no shelter for large groups which will be increasing in number, especially with the accessibility of the area to adjacent new superhighway facilities.

A staunch Mound City Group advocate, Cotter called for a collection and research policy with emphasis on museum displays and curatorial services. Cotter concluded stating, "It has taken the National Park Service many years to arrive at the conclusion that Mound City Group is worthy of inclusion in the System as nationally important. It may not yet be realized by the Service that Mound City Group is a major archeological resource in the Nation and the best-developed remaining site of the great Hopewell culture manifestation of American prehistory." [60] Although the park had its own informal collection policies, programmed funds for a formal collection management plan did not materialize until 1984. [61]

Escalated national defense spending, mushrooming of the national park system, and other planning priorities stalled the visitor center expansion project. In 1977, the monument's "space crunch," always a problem, became critical. Superintendent Fagergren noted the cramped visitor center office space, 139 square feet, accommodated six employees during winter (twenty-three square feet per person) and nine employees during summer (15.4 square feet per employee). The maintenance shop featured an office for the maintenance work leader and maintenance worker. Three Youth Conservation Corps employees had a small area in connection with a classroom for YCC enrollees during the summer. Library space, artifact storage, and interpretive work space were also jammed into the building. The crowded conditions necessitated expansion of the visitor center to include an audiovisual room and auditorium as well as a research laboratory and collection storage area. Fagergren tagged it as the monument's top project, and hoped for funding within two years. [62]

Unfortunately, it received a low national priority for funding. Projections were that a visitor center expansion would be "many years" in the future. No longer willing to rely on storage accommodations at the Ohio Historical Society, Fagergren wanted all Mound City Group artifacts kept according to professional standards at the monument. In August 1980, Fagergren adopted a new strategy. He proposed modifying the existing artifact storage area in the maintenance building's basement to accommodate curatorial services. He suggested enclosing one end of the basement with a special curatorial room complete with environmental stabilization systems. [63]

Anticipation of potentially large private collections being donated to Mound City Group prompted a 1990 effort to expand the collections storage area in the maintenance building's basement. Artifacts were moved into new storage cabinets and separated with archival materials. Curators also cataloged the collection using the Automated National Cataloging System for the first time. Mitigation of elevated radon levels in 1991 allowed for the expansion and rehabilitation of the basement area to proceed. The work brought about a tripling of storage capacity, including use of a track and carriage system for museum storage cases. Curatorial services also benefitted by adjacent office and workshop areas in 1991. [64]

In 1980, the first collections inventory undertaken since the 1960s revealled missing artifacts and confusion regarding past recordkeeping methods. Artifacts unearthed during Ohio Historical Society excavations were processed and cataloged using state methods. Returned to Mound City Group in the mid-1970s, the material did not immediately receive National Park Service catalog numbers on individual pieces. The Ohio Historical Society material, received in boxes and sacks, did not remain safely inside marked containers and the separation resulted in loss of their requisite numbering system. The situation became especially acute following the 1980 inventory when objects packaged and organized according to catalog numbers were loaned for study purposes and subsequently returned packaged and organized according to type. The absence of professionally trained cultural resource managers, specifically an archeologist and/or a museum curator, contributed to the deterioration of the Mound City Group collection.

This confusion, the result of different archeological curation methods of the Midwest Archeological Center, brought about two additional comprehensive inventories in 1984 and 1987. The latter effort took more than two months and yielded 33,069 objects covering 104 accessions. A board of survey conducted in 1988 resulted in eighty-four missing artifacts removed from the inventory. In 1991, Park Ranger Robert Petersen began an item by item review to develop a list of controlled property, with miscellaneous items accessioned and cataloged at the end of the multiple-year effort. By the mid-1990s, the park finally had professional accountability for its collections. [65]

One of the most extensive private collections in Ross County first came under consideration for donation in January 1990. Robert Harness informed Superintendent Bill Gibson of his intention to will his significant Hopewellian collection from the Liberty Works to Mound City Group National Monument via negotiation of an appropriate codicil. A draft agreement reviewed in late 1991 brought a prompt ruling that language prohibiting repatriation or any other restriction could not be accepted under National Park Service policies. Robert Harness, wanting professional care of the Harness collection and making it available for research purposes, did not want it broken up, removed from Ross County, or subjected to repatriation challenges. A compromise came in the formation of the Harness Collection Trust. In exchange for a signed deed of gift form pledging unconditional donation for unrestricted usage, the trust was devised to dissolve eight years after the formal donation. According to Gibson, "As the Trust comes into being and manages the collection, we can look forward to exploring alternative language to that presented in the draft agreement. Surely people with good intentions can come to agreement on a safe, secure and permanent home for this outstanding collection." [66]

Future plans recognize expansion of collections and increased burdens relating to the curatorial program. The 1997 general management plan calls for removing the museum storage area from the basement of the Resource Management Building, what once served the park's maintenance and utilities functions. Subject to flooding and fire, the curatorial storage will be relocated to a new facility or placed within an expanded addition to the visitor center.

Native Americans and the Human Remains Issue

The tumultuous 1960s and early 1970s saw a fundamental shift in American social and cultural institutions to reflect changing public attitudes concerning class, race, and gender. One aspect of this period of social upheaval, initiated by the Civil Rights Movement for African Americans, concerned native Americans and the formation of various American Indian rights groups. As Indians asserted their constitutional rights and discussed past injustices, all aspects of white-red relations were reexamined. During the 1978 "Longest Walk" across the United States, Indian rights activitists called attention to museums along the route that displayed Indian bones and grave goods, denouncing the practices, and calling for repatriation and reburials. It brought the Indians' conflict with the professional anthropology and archeology community into the public arena for bitter debate.

Changing federal perceptions yielded congressional action. In 1978, the Native American Religious Freedom Act (Public Law 95-341) brought an operational and administrative review throughout the national park system for potential conflicts with the new law's intent. The Mound City Group review identified the two exhibits of authentic cremated remains as well as the partial human remains represented in the park's collections. Fred J. Fagergren noted that because no native group claimed ties with any of the Eastern Woodland Moundbuilders, including the Hopewell, there existed the "possibility that Native American groups in general might object to these procedures as being offensive to their religious practices." [67]

Nonetheless, the ongoing debate prompted a change in the monument's interpretive program. In June 1978, the park accepted a local donation of an assortment of human bones of no known association for use in interpretive programs. The remains were not accessioned into the permanent collection. After using the bones in several programs, park interpreters concluded their use was inappropriate, and decided to rebury them. Encompassed in a polyethelene bag and sealed in a plastic bucket with a galvanized dated metal tag, the interpreters buried the package in Mound 13 on December 4, 1979. Adajacent to the mica grave exhibit, the burial is marked on the exhibit's blueprint. [68]

In 1979, the Archeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA, Public Law 96-95) stated that archeological resources found on public and Indian lands were part of America's heritage and were therefore protected from unauthorized taking. Archeological resources of more than one hundred years of age could also include graves and skeletal remains. ARPA guidelines were first promulgated in 1984, developed by an interagency task force and subject to public review and comment. American Indians led the call for new regulations to separate human remains from generic archeological resources covered by ARPA, to promote repatriation and reburial.

The debate raged on in the middle and late 1980s. Mound City Group managers pointed out that most of the human remains at the monument were in the form of cremated ashes. Press accounts noted that the museum's cremation display was designed by an American Indian who intentionally placed the ashes at ground level in order that visitors who viewed them would respectfully have to bow their heads while standing in front of the exhibit. An alert in late 1986 to the monument warned of a potential visit by a registered lobbyist for the National Congress of American Indians gathering data for congressional hearings on proposed repatriation legislation. [69]

A management review of Mound City Group practices evaluated the issue of displaying cremated remains of five individuals, one in the museum and four at the mica grave exhibit. While recognizing the sensitivity of the issue, the monument had not received any protest from individuals or groups. Ken Apschnikat speculated that the reason stemmed from "the cremations themselves not resembling human remains and because no known contemporary tribe can trace their ancestral line to the Hopewell." Apschnikat acknowledged the potential for future complaints, noted the existence of human remains in the stored museum collection, and pledged to "continue to treat these human remains and objects with reverence and dignity." [70]

Chief of Interpretation and Resource Management H. Reed Johnson conducted an indepth analysis in 1989. Noting the extinction of the Hopewell culture and no proven ancestral link to historic American Indian cultures, Johnson asserted that artifacts and remains were displayed in a "respectful manner." Johnson noted that "While the exhibits contain partially cremated remains consisting of bone fragments, they are displayed 'in context,' that is, they are depictions of the actual cremations and burials as they were performed by the Hopewell." He recommended that removal or modifications to these exhibits could be done as part of the next programmed rehabilitation of museum exhibits, which should also include consultation with Indian groups during planning and design. Unidentified bones in the collection required study to determine human or animal origins. Future excavations uncovering human remains would involve reinterment as soon as possible following exhumation. [71]

Park plans to alter the exhibits ceased in early 1990 following a review by Associate Director for Cultural Resources Jerry L. Rogers. Rogers' review came in anticipation of passage of the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) of 1990. The last skeletal remains on display in the national park system were removed from Mesa Verde National Park in 1987 following a request by American Indian groups. Rogers, concerned that human remains were still on display at Mound City Group National Monument three years after this incident, called for their immediate removal. Superintendent Bill Gibson ordered his staff in February 1990 to comply, requesting clean sand appear in the cremation pit bottoms. [72]

A concurrent review of the collection for human remains yielded inhumation of forty-two individuals and cremations of thirty-seven individuals, totalling seventy-nine representatives associated with the Hopewell culture. Unidentified remains of questionnable origins included ten inhumations and five cremations believed to be associated with either the Hopewell or possibly the later Intrusive Mound Culture. Asked to identify Indian groups for regulatory consultation purposes, H. Reed Johnson identified the Shawnee tribe of Oklahoma as the "closest officially recognized leaders" of the southern Ohio region. Their geographical dislocation made consultation "somewhat difficult." [73]

Completing the NAGPRA-mandated inventory of human remains and associated funerary objects in park collections, Dr. Paul S. Sciulli of Ohio State University performed the work via a cooperative agreement between the Midwest Archeological Center and the Ohio State University Research Foundation. The effort provided information on the age, sex, and cultural affiliation of human remains and related burial items, and park curators updated in excess of five hundred records for more than 18,000 items. About three thousand documents were also catalogued. [74]

Consultations with American Indian groups required under NAGPRA began in July 1994, when representatives of the Joint Shawnee Council on Repatriation visited Mound City Group. Council members are volunteers from three federally recognized tribes comprising the Shawnee Nation. Subsequent consultations took place in March 1995, when Council representatives again came to the park, and in April 1995, when NPS officials traveled to Oklahoma. The joint effort laid the groundwork for a July 5, 1996 memorandum of agreement for treatment and disposition of past or future American Indian remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, or objects of cultural patrimony found within park lands. The successful federal-tribal consultations prompted Hopewell Culture staff to host an April 1995 NAGPRA workshop attended by NPS employees, the Joint Shawnee Council, and members of the Ohio Museums Association. [75]

Thanks to NAGPRA's establishing a federal commitment to consult American Indians, in 1996, NPS responded to expressed concerns over its interpretation of Hopewell burial practices, and removed the mica grave exhibit. Through consultation, agreement was reached that more appropriate ways of conveying mica grave information using different media could be accomplished. Such native input also helped enrich an interpretive prospectus revision, thereby for the first time reflecting American Indian perspectives in Hopewell Culture interpretation. [76]

Lack of sustained funding and making do with substandard facilities have hampered NPS efforts in Chillicothe to present the Hopewell culture on the same scale and quality as Southwestern prehistoric cultures are presented in collective NPS units of the American Southwest. With its transformation into a national historical park in the early 1990s, expanded staff and facility needs will likely continue to be key issues through the initial decades of the twenty-first century.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

hocu/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 04-Dec-2000