|

Hubbell Trading Post

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER I:

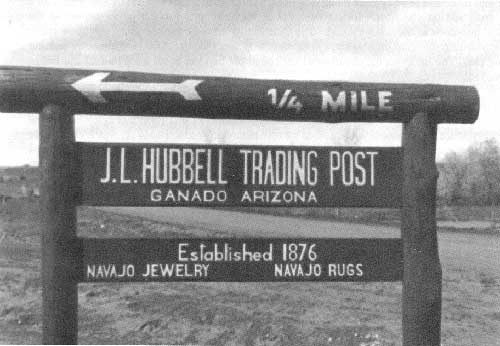

HUBBELL TRADING POST, JULY, 1957

The Birth of an Idea

"I am sending you, under separate cover, the pen used by President Johnson in signing the Hubbell Trading Post bill. This is something you deserve." So wrote Morris K. Udall, Congressman from Arizona, in a letter dated September 20, 1965, to Dr. Edward B. Danson, Director of the Museum of Northern Arizona. Morris Udall was referring to the eight years of extraordinary dedication on Danson's part in keeping the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site movement alive in Congress and in the minds of many private citizens in the face of persistent opposition. Ned Danson still has the pen--as well as the satisfaction of being the prime mover during the long effort to save the old trading post for the American people.

|

| Figure 8. Photograph taken February 11, 1958, by K. Wing and C. Steen. The original east-west road through Ganado ran right past the front of Hubbell Trading Post. The state road was straightened and now runs across the far northeast comer of the site property. NPS photo, HUTR Neg. 1. |

On a July day in 1957, Ned Danson, then Assistant Director of the Museum of Northern Arizona, and Dr. Harold Colton, the Museum's director, drove over to Ganado from their offices in Flagstaff. [1] They were going to visit with Dorothy and Roman Hubbell at Hubbell Trading Post, their main purpose to arrange for the loan of artwork for an exhibit at the Museum. They were interested in borrowing some of the red conte crayon sketches by E.A. Burbank. These sketches, the so-called "Redheads," are portraits of many Native Americans including local Navajo and other citizens of Ganado, and also a profile of J.L. Hubbell. Burbank was one of the habitues among the artists who had accepted Don Lorenzo's hospitality. Dozens of the Redheads line the walls of the Hubbell home.

For Ned Danson, that drive in 1957 to Hubbell Trading Post was a trip through time as well as space; he had been to Ganado before, way back in June of 1926, the year his parents decided to take the train from their home in Cincinnati, Ohio, and tour the West with their two daughters and their ten-year-old son, Ned. [2] The real western adventure started when the Super Chief rolled into Las Vegas, New Mexico, where the Danson family was met by one of the monumental Packard Eight touring cars of the Indian Detours. [3] The cars were chauffeured by men wearing flannel shirts and ten-gallon hats, and young women dressed in Navajo-style blouses and wearing silver and turquoise jewelry rode along as guides. The Packard rumbled out of Las Vegas on a dusty road and up and over Glorieta Pass and down into Santa Fe, the guide answering the tourists' questions as they drove along. The Ohio family stayed over in Santa Fe to see a rodeo before boarding the train once again. Their next stop was Gallup. They were met by another touring car. The dudes in the chauffeured car rolled off into the north for a tour of the Indian reservations.

The impressions gained on those early tours have remained a part of Ned Danson. He still remembers how the long hood of the Packard would swing back and forth through what looked like empty space as the automobile climbed narrow mountain roads. The West was a vivid place for a boy to be and the 1920s was a good time to be there. Plenty of windows to the old West remained open. A boy could still meet the folks who had settled the country and he could see some of the Indians who had survived that settlement. Pioneers and colorful Indians were on hand to greet the Kodak-toting tourists who bounced into town and encampment in their newfangled machines.

Settlements in the West and away from the railroads were still usually without satisfactory tourist accommodations. (One early motorist, struggling through Wyoming, came upon a one-room "hotel" fashioned out of old railroad ties. [4] For some, the so-called accommodations were so disgusting that they often preferred to sleep under the big sky [5] ) However, if evening happened to catch up with you as you pulled into Ganado, Arizona, you could probably find free room and board at Hubbell Trading Post. Don Lorenzo was well known for his hospitality, and it was very likely you wouldn't be the only guest there. As Dorothy Hubbell has pointed out, they were never sure how many people they would have for dinner. [6]

The Danson family stayed at least one night at Hubbell Trading Post. Dorothy Hubbell could have been there. Don Lorenzo and Roman Hubbell could have been there. Ned Danson doesn't recall seeing them. What he does remember about the trading post of 1926 was that he shared a spare bedroom with his parents. He slept on a cot, his mother and father in a big brass bed.

And now it was 1957. Ned Danson had become Dr. Edward B. Danson. He was forty-one, married, and had children of his own. During the intervening years he had studied history at Cornell and anthropology at the University of Arizona. His doctorate in anthropology is from Harvard. Prior to his appointment to the Museum, he taught two years at the University of Colorado, at Boulder, and six years at the University of Arizona. But what made a man of him, he enjoys relating, were the two years he served aboard the schooner Yankee. [7]

A world map with the Yankee's 1933-1935 circumnavigation traced on it is attached to an exterior wall next to the door of Danson's study in Sedona, Arizona. The Yankee sailed south out of Gloucester, Massachusetts. Through the Panama Canal and across the Pacific with the trade winds-the Galapagos, Pitcairn Island, Tahiti. Then across the Indian Ocean to Africa. Durban, Capetown, and around into the Atlantic. St. Helena, Ascension Island, Bermuda. And home. Eighteen months of clambering through the rigging of a tall schooner in all kinds of weather. Danson was just seventeen when he sailed out of Gloucester in 1933. Indeed, if a boy is so created that he can be molded into a man, a little time at sea is a surefire way to push the process along.

But if a lot of water had rolled under some bridges--and a tall ship--for Ned Danson since 1926, the same was not apparent for Hubbell Trading Post. Well, the pickups and automobiles parked outside the trading post now outnumbered the horses and wagons that prevailed in 1926, but the same fortress-like buildings still hunkered on the earth as if having survived their own colorful pioneer era, they were now prepared to wait out eternity. Hubbell Trading Post still maintains its aura of timelessness.

|

| Figure 9. The trading post Bullpen in 1949, clerk Pete Balcomb waiting on Slim Tahe (Hastin Besh'ii'aahe Biye), the man in the leather jacket who is facing the camera. Except for a change of products on the shelves, the Bullpen still looks like this. Mullarky Photo Studio, Gallup, New Mexico. HUTR Neg. RP-188. |

The lives and affairs of man are more transitory. Don Lorenzo had died in 1930. Dorothy Hubbell was just fifty-eight. But husband Roman Hubbell was now confined to a wheelchair. He had suffered a slight stroke in 1953, and then a series of small strokes had left him gradually paralyzed on his right side. [8] Hubbell Trading Post, Inc., a business empire that had once included several other trading posts, ranchlands, farming, and an automobile touring company, Roman Hubbell Navajo Tours, similar in intention to the Indian Detours, had been reduced to Hubbell Trading Post itself and was in bankruptcy. Roman Hubbell, by all accounts a charming man who could handle passing tourists with ease and consideration, had never been the trader his legendary father was. And now he was desperately ill. Dorothy Hubbell was carrying on as best she could, running the trading post and caring for Roman, but it had become too much for her.

The meeting between Harold Colton, Ned Danson, and the Hubbells took place around the middle of July, 1957. Once the arrangements for the loan of Burbank's Redheads had been concluded, Roman looked at Dorothy and said, "Should we say something?" She nodded and said "Yes." [9] As the Hubbells explained to Colton and Danson, with Roman ill, they were just no longer able to continue running the trading post. One of the Hubbell boys, Roman, Jr., had been killed during World War II. The other Hubbell son, John, was an instructor of Spanish at the University of Vermont. Although John showed up at the trading post during summer vacations to help out where he could, he had no intention of becoming an Indian trader. LaCharles Eckel, a niece of the Hubbells who had done a lot of her growing up at the trading post, now lived in Denver and was married and had children of her own. Her family responsibilities would keep her away from the trading post.

And so Hubbell Trading Post, founded over seventy-five years before by Juan Lorenzo Hubbell, was for sale. The Hubbells had already entertained offers. But what the Hubbells wanted to know from Dr. Colton was whether there would be any way for the Museum of Northern Arizona to acquire and preserve the property.

No, Dr. Colton said, the Museum could not acquire the trading post. He went on to explain that they were a private scientific institution dedicated to the study of geology, biology, anthropology, art and atmospherics. A trading post in the middle of the Navajo Nation would not fall within their purview. Dr. Colton was one of the founders of the Museum. He knew as well as anybody could just what the Museum would be able to absorb. And on that negative note, Harold Colton and Ned Danson started back to Flagstaff.

As Dorothy Hubbell explained later, her decision to approach the Museum of Northern Arizona was inspired to a great extent by what had happened to the Richard Wetherill property at Kayenta, another trading post. The Wetherills were a well-known family in the Four Corners region, ranchers in southwestern Colorado, who came to prominence in the late nineteenth century as the "discoverers" of the ruins at Mesa Verde. [10] Theirs were the first "digs" in many Anasazi ruins all over the Four Corners area. At the same time they became involved in trading posts on the Navajo Reservation, and their interests in trading posts lasted for decades after they gave up exploring and archeology. Over the years the Wetherills amassed an enormous collection of ancient and modem Indian artifacts.

Dorothy Hubbell first met the Wetherills when she was still a newcomer to the country. "I was greatly impressed by the number [of artifacts] they had," Dorothy related. "And I was interested because it was new to me then, too. Then they died and it was only their son, Ben, alive. And then Ben moved away. The place was sold, everything was gone. Everything was gone. Nothing was collected, put into a collection where it could be studied. It was gone. I thought, well, now, what would happen to Ganado [Hubbell Trading Post] if I sold to somebody?" [11]

|

| Figure 10. Roman and Dorothy Hubbell. The date is probably the late 1940s HUTR Neg. R28#8. |

The Hubbells were approached by at least three different parties who were interested in the property. Dorothy: "And this one man to whom I talked, I said, What would you do with these things?' I was pointing to the walls 'Oh,' he said, 'I would just sell them. I'd put in a liquor store'." Dorothy was appalled. Well, in any case, the Navajo would never have permitted a liquor store to become part of the trading post, but--could she stand to see so many of the beautiful things contained in the Hubbell homestead sold off! To just anybody? Would the Hubbell property have to suffer the same fate as the Wetherill's? Dorothy: "That let me know that some people might just disperse the things that we had. And I had lived with them long enough that they seemed important to me." [12]

Dorothy had lived with them since 1920. Born Dorothy Elizabeth Smith in Indiana, Dorothy came west in 1920 to be teacher to the Hubbell children. Roman's wife had died during the influenza epidemic that spread across much of the world just after World War I. Seven months later--to the utter consternation of her parents--Dorothy was married to Roman and became stepmother to her pupils. [13]

The Hubbells, too, had gathered an impressive collection of Indian artifacts and modern art: floors covered with Navajo rugs, walls hung with artwork and Indian baskets, baskets from many Indian tribes of the Southwest nailed to the ceilings between the vigas, pottery from all of the southwestern tribes. The furniture was mostly period Victorian, and like many a bourgeois turn-of-the-century home, there seemed to be an excessive amount of everything. A traveler, marooned in 1907 by a time warp, would have felt right at home at Hubbell Trading Post in 1957. As Ned Danson suggested, "It was a hodgepodge of things...." [14]

Hodgepodge, to be sure, but in many respects valuable. Apart from the historical and ethnological value of the contents of the trading post, a way of life had been--to an almost incredible degree--preserved there. For Dorothy Hubbell, that way of life was still tangible. (Several times while being interviewed for this administrative history, when people from her past were mentioned, she would pause, as if caught unawares, and say, "And now they're all gone." Seventy years had slipped away.)

Dorothy was determined to see Hubbell Trading Post preserved: "It was important enough that I didn't want to see it dissipated." But with Roman's health so frail and business slow.... If the Museum of Northern Arizona couldn't take the old trading post, an eventual sale to disinterested strangers would be its inevitable fate.

During the two-hour drive back to Flagstaff, Danson and Colton continued to mull over the Hubbell's offer and their precarious situation. But as far as they could see, there was nothing in the Museum's mandate that would allow them to pursue such an exotic acquisition. Ned Danson, however, had recently become a member of the National Park Service Advisory Board. As he drove through the late afternoon, he was at last inspired by the notion that Hubbell Trading Post might be a candidate for the National Park System. He put the idea to Dr. Colton, who agreed that the idea had merit. Danson decided that the next time he went to Washington for a Board meeting he would put Hubbell Trading Post on the table for discussion. [15]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

hutr/adhi/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006