|

Hubbell Trading Post

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER II:

LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

Ned Danson Looks for Help

By all accounts the exhibit of Burbank's Redheads was a success and the drawings were returned to Hubbell Trading Post on September 21, 1957. During the exhibit, sometime in August, NPS Regional Archeologist Charlie Steen happened to be at the Museum of Northern Arizona, and while Steen was there Ned Danson took advantage of the opportunity to tell him about the availability of Hubbell Trading Post as a possible NPS acquisition. [1]

|

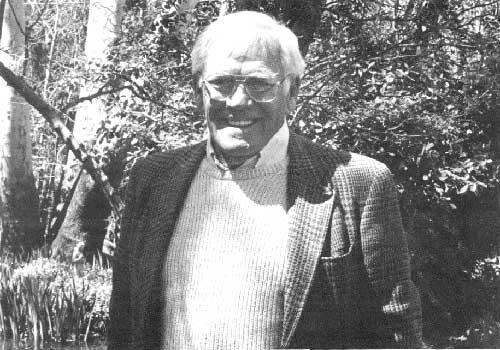

| Figure 11. Dr. Edward B. Danson in the backyard of his home in Sedona, Arizona, on April 18, 1991, the day the authors interviewed him for this history. A Manchester photo. |

Steen recorded some details about the trading post so that he could report to the Regional Director, but he also advised Danson that chances were probably pretty slim that an appropriation could be pried out of Congress to buy an old trading post in Navajo country. Furthermore, Steen continued, the Park Service could not take it upon itself to explore for prospective sites, parks, or monuments. Steen didn't know of a written directive that prohibited a Park Service search for new areas, but any investigations the NPS might make in reference to a prospective acquisition were always made only at the request of a member of Congress. Danson mentioned that he was considering writing to his Congressman about Hubbell Trading Post; Steen encouraged him to do so. Steen explained that if one of the Arizona Congressmen was sufficiently interested in the site, he could ask the Park Service to appraise the land and buildings and also make an assessment of the trading post to see if its historical value was sufficient to qualify it for some kind of preservation with federal money. [2]

Ned Danson wrote several letters to Arizona Congressmen. Representative Stewart L. Udall asked his administrative assistant in Washington to present a proposal to NPS Director Conrad Wirth immediately. [3] Senator Carl Hayden forwarded Ned Danson's letter to Director Wirth and asked him to "give serious consideration to taking [Hubbell Trading Post] over as a National Monument." [4] Senator Barry Goldwater asked Director Wirth to "institute studies leading up to a determination of the advisability of creating a national monument where the Hubbell Trading Post stands in Ganado, Arizona." [5]

Ned Danson was not shy about spreading his enthusiasm. But unknown to him at the time, interest in the old trading post for all the Congressmen went back many years.

Barry Goldwater, Carl Hayden and Stewart L. Udall Made Early Trips to Ganado. [6]

It was probably Barry Goldwater's mother's interest in her adopted state (she had moved to Arizona from the Midwest for her health) that nurtured his own love for Arizona. For as far back as Goldwater could remember, his mother would take her children on motor tours around the state, and that was long before it was common practice for most motorists to risk the machines in the hinterland. As Goldwater recalled, roads could be so rough and tires so flimsy that the travelers might have to change tires four or five times in a hundred miles ("We could change those tires with our eyes closed."). Travel as arduous as that takes courage and a strong sense of adventure, the very stuff or pioneers---and dedicated early motorists.

Goldwater was seven years old in 1916 when he accompanied his mother on an automobile trek through Hopi and Navajo lands. He regards that trip as among the most wonderful experiences he's had. The Goldwaters stopped off in Ganado for several days. Barry Goldwater met Don Lorenzo, remembers him as being "very kindly," and he got to know Don Lorenzo's children. Goldwater saw the Redheads "...done by an artist who devoted his art to Indian faces, a Mr. Burbank, from California...."

As far as Barry Goldwater is concerned, Hubbell Trading Post was "...superior to any other Post we ever visited, and it still is to this day. Hubbell's remains "...a lot like when I first saw it." The old trading post made a "deep impression" on the future Senator. "Even after [Lorenzo Hubbell's] death, we would go to the post, stay there, and enjoy the whole area." "Always in my mind that was just the way a Navajo post should look." He was so impressed by Burbank's Redheads that in later years he acquired a few from the trading post.

Ned Danson had found one enthusiastic supporter, but in Senator Carl Hayden he would find another. Born in what is now Tempe, Arizona, in 1877, Senator Hayden was already a member of Congress when in 1915 he made his first trip to Ganado: "I...found Don Lorenzo Hubbell actively engaged as a Navajo Indian trader. I was told that he was the son of an American pioneer whose wife came from a prominent Spanish family in New Mexico. Don Lorenzo was then recognized as the most successful of all the traders in the Navajo country." [7]

And yet another traveler to Hubbell's was Stewart L. Udall, who was only ten years old when he accompanied his father there during an early 1930 political campaign (his father was a judge). Udall's grandfather and Lorenzo Hubbell had become political enemies during the 1880s but they resolved their differences in the late 1920s when Lorenzo was dying. As Udall remembers that early visit, he found the old trading post "redolent of the 19th century." He never forgot the place. [8]

So all of the Congressmen had visited Hubbell Trading Post way back when. Two of them had known Don Lorenzo. They had seen Hubbell's in the heyday of trading posts when it was an important element in the culture and economy of the Navajo. During the following years, their continued support would prove vital for the success of the Hubbell Trading Post national historic site movement.

Sometime during August, 1957, while on another visit to Ganado, Ned Danson explained his National Park Service idea to Dorothy Hubbell. As far as she was concerned it was the best solution she had heard. On September 27, Danson wrote to Mrs. Hubbell to advise her that he had received favorable responses from Senators Hayden and Goldwater and Representative Udall. Danson continued: "This is just the beginning of the process of getting the Park Service to approve the acquisition, and I am sure you understand that this will take some time. However, I feel a good start has been made and I am optimistic." [9]

A good start. Optimistic. But it will take some time. Yes, it would take some time...

The National Park Service Goes to Work-Roman Hubbell Dies

Ben H. Thompson, NPS Acting Director, replied to the Congressmen to advise them that Hubbell Trading Post would be investigated during the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings then underway. However, funds for the work were limited and he was not certain as to when the survey would be completed; but he did feel that Hubbell's would be among those places considered to determine whether or not it was "nationally important and suitable for national monument purposes." [10] Also, the NPS Regional Office in Santa Fe was ordered to forward whatever data on the old trading post that might be readily available. The NPS would be concentrating their attention on western sites, and it was hoped that the "broad aspects" of the survey would be completed by the end of the 1958 fiscal year. [11]

Efforts for the hoped-for disposal of Hubbell Trading Post to the NPS had hardly gotten under way when Roman Hubbell died, in October of 1957, aged only sixty-five years. He was the last of the original Hubbell clan. Dorothy was left to maintain the trading post as best she could. And in Washington the mill wheels of procedure started to turn ever so slowly.

And Ned Danson was hedging his bet. Aware of the economy drive in Congress, and at the suggestion of Dr. Colton, Danson wrote to Philip Merkle, of the Arizona Republic, to see if there might not be enough people in Arizona and possibly outside the state to contribute enough money to buy the trading post. Also, Dorothy received a letter from Dr. Hopkins, retired professor of journalism, who thought that the trading post should be preserved intact as a museum of Arizoniana, and he was sure that possibly the Heard Museum--or a foundation of public spirited citizens-could be induced to help with the matter. Many people who were interested in Hubbell Trading Post were also determined to preserve it intact.

The National Advisory Board of the National Park Service Joins the Act

At the next Board meeting of the Advisory Board of the NPS, in the spring of 1958, Ned Danson put Hubbell Trading Post on the table for discussion. The Board members were receptive to the proposal but decided not to act on it because, as yet, the Park Service had not completed its survey of the site. Dorothy Hubbell was advised that chances were good that Hubbell Trading Post would eventually be included in the Park System. [12] In the meantime, the Southwest Regional Office of the NPS would be putting together a study of Hubbell Trading Post, and Robert M. Utley, Regional Historian, was in charge of--and doing most of the work on---the project.

Robert Utley's Special Report of Hubbell Trading Post, Ganado, Arizona, for The National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings

While Dorothy Hubbell waited and Ned Danson talked and wrote, Robert M. Utley, Regional Historian, went to work on the Hubbell Trading Post study, completed by January, 1959. His job was to "...come up with...an analysis of Hubbell's role as an Indian trader and his influence on the Navajo, but also with an analysis of the role and influence of the Navajo trading post as a reservation institution and the role and influence of Indian traders throughout the West." [13] This "study" developed into a 108-page document that has since been a good starting point for many studies about the trading post (including this one). Complete with maps and photos, the report was forwarded to Park Service headquarters, Washington, D.C., where, in February, 1959, an 18-page unsigned critique of it was issued.

In order to shorten the 18-page critique to a long paragraph, it should be enough to say that the Branch of History, National Park Service, Washington, D.C., was not enthusiastic about Hubbell Trading Post becoming a national monument. Don Lorenzo's influence on political, economic, and cultural affairs was, they thought, restricted to only a part of the Navajo Reservation, nor did they feel that Bob Utley had demonstrated that Navajo Indian traders were of national significance. The Branch of History reviewed four other letters and documents in reference to Hubbell Trading Post, but Utley's was the report they most relied on, and they thought an important weakness was its lack of a complete list of the ethnological and cultural objects he said were at the trading post. (At that time there was no complete list of the thousands of artifacts, nor would there be a complete list for a long time to come.) They knew Burbank's artworks were important, but they thought, too, that the Smithsonian would be a good place for that part of the collection. Not only was the trading post not of national significance, as far as they could see, Hubbell's was only important as far as part of the reservation was concerned. Hubbell Trading Post possessed no exceptional value for commemorating the cultural, political, military, or economic history of the United States; none of the members of the family had any important significance in the history of the United States; the trading post did not appear to have any association with important events which are symbolic of any great idea or ideals of the American people; the buildings at the trading post did not constitute notable works of a master builder, designer, or architect whose individual genius reflected his age; nor were the archeological sites of major significance. It was admitted, however, that the structures there were over fifty years old. And had integrity and original workmanship. It was decided that the trading post did not possess that exceptional value commemorating or illustrating the history of the United States necessary to give it an evaluation of national significance. The recommendation of the Branch of History was "that the State of Arizona or some suitable regional agency consider steps that may be taken to preserve the Hubbell Trading Post." [14]

So Hubbell Trading Post was good enough for the State of Arizona but not good enough to become a unit of the National Park Service, at least as far as the Branch of History was concerned. In the meantime, everybody who was interested in the trading post project knew that Dorothy Hubbell would have a hard time working the post alone, and efforts were made to see if money could possibly be raised by the people of Arizona in order to buy it. [15] Or some "suitable agency" might be found that would find the trading post worth preserving, The Navajo Tribe considered the purchase, but they decided that Dorothy Hubbell's asking price was too high. [16]

Although Bob Utley's report failed to win over his counterparts in Washington, he still cherishes those days when he was doing research at Hubbell Trading Post. Utley: "I have warm memories of Dorothy Hubbell.... With a research assistant, I spent several days as a guest in her home, occupying the Burbank-bedecked bedroom on the left as you enter the front door. She presided in regal splendor over the big table in the dining room, in much the same fashion, I have thought, that Don Lorenzo himself presided over the same table. She tricked me into a boast that one should keep an open mind toward all forms of food and refuse nothing that had not been at least tried; she presented me with a can full of chocolate covered grasshoppers, which I could not bring myself to sample. ...I spent several days there...to go through the Hubbell papers, which were thrown into barrels in the barn and were well sprinkled with evidence of the passage of rats and other influences antithetical to the professional preservation of archival material." [17]

But as it turned out, Bob Utley's intrepid explorations and investigations--even through rat droppings--were not in vain. As soon as Ned Danson heard that Utley's report was available, he requested a copy from SWRO; [18] if Hubbell Trading post was going to be put on the table for discussion at the April meeting of the National Park Service Advisory Board, Ned wanted all of the other members to read it. [19] Something swayed the Board in the direction of Hubbell Trading Post; on the 22nd of April they recommended that Hubbell Trading Post be classified as of exceptional value under the terms of the Historic Sites Act. They went on to recommend that the trading post be included in the National Park System: "The Hubbell Trading Post includes in its present make-up many intangible elements of feeling and association with important parts of American heritage. The Spanish element, the American element and the American Indian element are well represented. In addition the examples of western art preserved at the Post are significant Americana and part of the story of trading post life. This Post expresses a period of history as does no other known trading post, and its function as an acculturating agent continues to this day among the Navajo and Hopi Indians which tribes it has served since its founding in 1876.

"Further, the Advisory Board recognizes that this Post is now available for preservation and that its loss would forever impoverish our understanding of a major phase of our heritage." [20]

Ned Danson wrote to Dorothy Hubbell to advise her of the Board's direction and to tell her that although there had been opposition in Washington, most of it seemed to be based on ignorance. [21] Dorothy was delighted with the Advisory Board's approval. Although Park Service personnel had been stopping by the trading post all year, she had begun to think that nothing would come of the idea. And Bob Utley had forwarded a copy of his report to her; and she found it "truly comprehensive" and it "raised my hopes considerably." [22]

Although the Branch of History was unmoved by Bob Utley's efforts, his report must have scored favorably with the people who counted. Today, over thirty years after it was written, and after a lot more research has been done on the subjects it delves into, the report is still a valuable source of information about the trading post and the Navajo. It was an important step in bringing the trading post into the National Park System.

S. 1871 and H.R. 7279

On May 7, 1959, Senator Carl Hayden introduced S.1871 to authorize the establishment of the trading post as a national historic site. [23] However, a necessary report from the Secretary of the Interior arrived too late for the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs to act on the matter, but Senator Hayden would urge early consideration of it after Congress convened in January. [24]

Congressman Stewart L. Udall introduced H.R. 7279 on May 20, 1959, for the establishment of the trading post as an historic site, but neither the House nor the Senate Committee on Interior Affairs held hearings on the bill.

The report that Carl Hayden said was needed for the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs was from the Office of the Secretary of the Interior and is a two-page description of Hubbell Trading Post. It mentions, too, that the owners of the trading post would be willing to part with the post for $300,000, and the assessed 1957 valuation of the real property, if noted, was $9,957. [25] This $9,957 amount, a figure for tax purposes, would become in the future a weapon for those opposing the Hubbell Trading Post bills.

H.R. 7279 passed successfully through the House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee during the first weeks of 1960. Everybody interested in the project felt something had to be done quickly; the general perception of Dorothy Hubbell's financial foundation was that it was shaky. Rumors had circulated that she was selling off some of the better artwork, which was not true; she hoped to deliver the trading post intact, including its rich contents, to the American people. Potential buyers of art, hearing the rumors, would stop by "almost every day" to see what they could buy. Dorothy told them all that nothing was for sale. [26]

Her gasoline sales had been cut in half when the road was moved away from the trading post to the northeast corner of the Hubbell land. And now the El Paso Gas Company was putting in a gas station just off her property. That would further reduce her dwindling sales of gasoline. However, Standard Oil had proposed to her that she lease some land in that distant corner to them for a gas station. Although she needed the income, she was afraid that the presence of the gasoline station on her property might spoil her chances of ever selling the entire property to the government. [27] But just how long could she wait for Congress to dance through its complicated routine? Ned Danson did his best to keep her informed of progress.

Opposition Arises to the Hubbell Trading Post Legislation

On March 4, 1960, Stewart Udall wrote to Ned Danson to advise him of some opposition to Hubbell Trading Post that was arising. [28] In a publication called Human Events. [29] Udall's legislation was described as a boondoggle that would cost the taxpayers thousands of dollars. And what would the government get for its money? "In return for its $600,000 now and more later, the government would get the Trading Post, 160 acres, and a collection of Southwestern art and Indian relics in a nearly uninhabited area of northeastern Arizona, 80 miles from the nearest town of any size, 200 miles from the nearest city." [30]

The owners of the property would sell for $300,000 (the other $300,000 was intended for development). Representative H.R. Gross (R. Iowa) suggested that the owners of the trading post would no doubt be willing to sell for that amount. The 1957 assessed valuation was $9,957!

The letter went on to say that citizens should make a "PUBLIC PROTEST from now until election---when 'pork barrel' congressmen can be replaced by men willing to work for fiscal sanity." [31]

Representative Gross had objected to the passage of the bill on the consent calendar; and now it appeared that Stewart Udall would have to secure the cooperation of Speaker Rayburn in order to have the bill brought up on a special calendar. This would not be the last time for the proponents of the Hubbell Trading Post legislation to hear from Representative Harold Royce Gross. [32]

H.R. 7279 came before the House on March 21, 1960. It was defeated by a vote of 208 to 171. Some excerpts from the debate:

Mr. Gross: "How much is the land around this trading post worth?"

Mr. Udall: "I do not know about that, but the real property, the buildings, is assessed at $9,000. As I say, however, property is assessed at 10 percent."

Mr. Gross: "With a few paintings and an ethnological collection, the price has gone up to $300,000. On top of that, the bill calls for $294,000 for redevelopment...and...$23,000 for federal management for this thing in the first year... I say to you again that if you vote for this proposition you are approving an expenditure of more than half a million dollars to bail out an estate in the wilds of northeast Arizona. I want no part of it."

***

Mr. O'Hara: "Mr. Speaker, I must answer to my constituents. I find here in report No. 1250 that the assessed valuation of the real property in 1957 was $9,957, and that the owner graciously had expressed a willingness to sell the property for $300,000. There may be an answer, but it will have to be a pretty good answer or I cannot look my constituents in the face if I vote for this."

Mr. Udall: "We discussed this matter.... I made two points: The first is that real property valuations for tax purposes in my State are about 10 percent.... But the real value of this trading post lies in the collection of Indian artifacts, art work, Indian blankets, and so forth."

Mr. O'Hara: "Allowing, as the gentleman states, the appraised value is one-tenth of the real value there still is a discrepancy of over $200,000, which has been explained very casually and with nothing on which to hang our hats."

***

Mr. Gross: "Has an appraisal been made of the Indian collection involved?"

Mr. Udall: "None has been made. There is to be an appraisal before purchase."

Mr. Gross: "Yes, but you want to spend, under the terms of this bill, $300,000 for the property without an appraisal of the collection."

Mr. Udall: "No, my colleague does not understand. The $300,000 is a limit. It will be appraised at fair market value, and that will be the price."

Mr. Dowdy: "This is obviously an attempt to bail out the owners of a worthless property at the expense of the American taxpayer." [33]

H.R. 7279 took some heavy bashing on March 21, 1960. Its companion bill in the Senate passed, and the Senate bill would now be introduced in the House. Both Barry Goldwater and Carl Hayden felt that they could get the bill through the House, but everybody now saw the necessity of having an independent appraisal done on all of the art and ethnological material at the trading post. [34] If the Congressmen needed something on which to hang their hats, they should have it.

Inventories and Appraisals

As Stewart Udall tried to point out, the true value of Hubbell Trading Post lay in its art and artifacts. Senator Goldwater and NPS Director Conrad Wirth suggested to Ned Danson that he have the trading post inventoried and appraised.

A "Rough Inventory of Ethnological and Art Collections-Hubbell Trading Post" had been done on the 5th of March, 1958. This room-by-room inventory does not include all of the artifacts and art at the trading post (a storeroom is described as "full of stuff"), nor does it attempt to put a dollar value on anything. It doesn't look like an inventory that might impress lowa's Representative Gross.

In order to get something on paper as quickly as possible, Ned Danson and Charlie Steen, with the assistance of Dorothy Hubbell, inventoried the trading post on the 19th of April, 1960. It was as complete an inventory as they could make in one day, and it was done by class of item, not by room. One has but to see the trading post in order to appreciate what a hard day that must have been. This inventory was sent to Carl Hayden to supplement the rough inventory he already had. Along with it went an inventory that Mrs. Hubbell had prepared some time before. [35]

In order to get the contents of the trading post appraised, Ned Danson enlisted the best men he knew, Clay Lockett, a dealer in Indian art who had a shop in Tucson, and Ivan Rosecrist, owner and operator of Rosecrist's Art Gallery in Tucson. The men would work without pay. They had no connections with either the Park Service or the Museum of Northern Arizona. William V. O'Brien, of O'Brien's Emporium, Scottsdale, would assist Mr. Rosecrist; and Tom Bahti, of Tucson, would assist Mr. Lockett. [36] The four men from Tucson, plus Ned Danson and his secretary (who would help with note taking), arrived at the trading post on the 20th of June, 1960. Mrs. Hubbell put them up in her bedrooms in the Hubbell home and in the Guest Hogan. [37] They worked for four days. [38]

The appraisals were ready by December. The total value for both the art and ethnological collection came to $111,536. This appraisal did not include the books, the house furnishings, nor the gun collection. If all of the other odds and ends around the post were to be included, the total value for personal property at Hubbell Trading Post was estimated to be about $120,000. [39]

They were now armed with accurate appraisals of the art and ethnological collection. That was all well and good, but would that stop Representative Gross from carping about that $9,957 assessed valuation of the trading post real estate? In order to go forward fully prepared, thought Hillary A. Tolson, Acting Director of the Park Service, they should also obtain appraisals of the land and buildings at the trading post. Carl Hayden agreed and he so informed the Park Service. (Land and buildings appraised at $169,000.) In the meantime, he had activated another bill for Hubbell Trading Post, this one S.522. [40] The bill passed the Senate, but again its companion bill foundered in the House. The same thing happened in 1962.

Hubbell Trading Post in Limbo

The Hubbell Trading Post bill remained in a state of limbo in the House. By 1963, even the apparently indefatigable Ned Danson revealed signs of discouragement: "I do not have the time or desire to work again on a 'lost cause,' but if all of you feel that there is a chance to add Hubbell Trading Post to the National Park System, I shall be happy to do what I can to get the information that will help you assure passage of the new Bill." [41] He had been asked by the Secretary of the Interior to institute a study of trading posts to see if there might be another one with the history and integrity to equal Hubbell's. He knew there was none. But he would see to the study anyway. It had been over five years since he had taken up the lance in favor of Hubbell Trading Post.... when it was claimed that Hubbell Trading Post was the best example of a trading post that still existed. Representative Gross said prove it, do your homework. In this case, it was up to Robert Utley, Regional Historian, to do the homework. Photographs and other information were duly gathered and sent on to Congress. It compared about a dozen of the old trading posts with Hubbell's, and discussed why, if any at all were to be preserved, the one to be saved should be the J.L. Hubbell Trading Post. [42]

In January of 1963, Carl Hayden introduced yet another Hubbell Trading Post bill, this one S.104. A new Arizona Representative, George F. Senner, Jr., introduced the companion bill in the House (H.R.3209).

Meanwhile, back at the trading post, Dorothy Hubbell traded indefatigably on. "I have been reading the newspaper notices and see that Representative Gross is most antagonistic. But, in all fairness, as I read the Congressional Record I find that he opposes most everything, and his comments have given me many a chuckle." [43] She had not lost her sense of humor (although the National Park Service would one day give her cause to do so). In spite of many good efforts, Hubbell Trading Post remained in limbo in Congress.

By 1965, the bills in favor of Hubbell Trading Post had become Senator Hayden's S.1137 and Representative Senner's H.R. 4901. Hearings were scheduled before the Committee on Interior and Insular affairs for the 21st of June, 1965.

The Origin of the Live Trading Post Concept

Like many other Park Service personnel, Director George Hartzog was apparently somewhat less than excited with the idea that Hubbell Trading Post should become a national historic site. "...he did not really want it. For a long time he didn't want it. Then I took him along, there one day and I think he and Mrs. Hubbell sort of got along." [44] So Dorothy Hubbell managed to charm even the Director of the National Park Service. And whatever else George Hartzog saw there, or heard there, or felt about the post would have a lasting impact on the old trading post; and what he decided about the future of Hubbell Trading Post, should it become a national historic site, was revealed on the morning of June 21, 1965, just before he and Ned Danson and Robert Utley were to appear before the Committee on Insular Affairs. [45]

Danson and Utley met with George Hartzog in the Director's office. Hartzog asked Robert Utley how he proposed to interpret the trading post. Utley: "I responded with a rather conventional approach of recreating a static exhibit, with period merchandise on the shelves and other features recalling the appearance of the various rooms in Don Lorenzo's time." [46]

The Director's reaction appalled Bob Utley. "Hartzog erupted vehemently that he would not countenance another goddamned dead embalmed historic site, that it must be a living trading post." [47] Besides being appalled, Bob Utley was shocked; all of the backup material they had been gathering for the hearing had been prepared with the idea that they would be offering the trading post as another museum-like historic site.

Utley, who at the time was Chief Historian, tried to argue Hartzog out of the idea. Where would they find an experienced trader? The Navajo would never allow themselves to be on display in front of gangs of tourists. But Hartzog had made up his mind, "and that, in emphatic and colorful language, was that." [48] And then Bob Utley was "stunned" when Ned Danson gleefully agreed with George Hartzog. Utley was outnumbered and outranked. Utley: "So we marched over to the hearings and George nailed us firmly to [the living trading post] approach in his testimony." [49]

An important excerpt from the House of Representatives Hearings before the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs (Subcommittee on National Parks and Recreation) in reference to H.R. 3320 to authorize the establishment of the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site, in the State of Arizona, and for other purposes:

Mr. O'Brien [to George Hartzog]: "I would like to ask one question. Throughout all the statements, including yours, you emphasize the uniqueness of this particular place. We are all aware, however, that there are other trading posts scattered around, some going to pot. Would it be the idea of the Department this would be selected not only because it is a good layout and historical but as a sort of a symbol of the trading post? We will not be having in the years ahead a whole string of former trading posts coming into being as historical sites? I do not want to close any doors in the future but I can see where sometimes there is a chain reaction. This would be a symbol of the trading post and a good one. There are plans that you know of in the future for setting up other places in that area?"

Mr. Hartzog: "Sir, this is what we consider to be, after surveying all of them, the best existing operating trading post. We would hope in our management to maintain it as an operating trading post. The operating trading post is fast becoming a thing of the past. Our study of it indicates that within a relatively few years there will be no more of them because of the competition from supermarkets, improved modes of transportation, changing tastes and what not. So that we believe that as an operating trading post this will be the only one.

However, in the very next bill that is before this Committee for consideration it involves Fort Union as a trading post to commemorate a somewhat different aspect of the interpretation of westward history. This is the one near the confluence of the Missouri and the Yellowstone Rivers. There are no buildings there. This is a site and we would not propose an operating trading post there.

This, Mr. Chairman, as I have mentioned in my appearances before this Committee, I believe is perhaps one of the more neglected aspects of our American history and its interpretation by the National Park Service in telling the story of the great midcontinent and what happened in terms of its settlement in this period prior to the passage of the frontier in 1890."

Mr. O'Brien: "Mr. Hartzog, I was not attempting to throw a roadblock in the way of the next bill or establishment, where desirable, of some other part of the country for historic site. I was thinking mainly in terms of let us say Arizona. We are not going to have every trading post set up?"

Mr. Hartzog: "No."

Mr. O'Brien: "You are going to maintain it and operate the trading post?"

Mr. Hartzog: "That is what we hope to do."

That's what George Hartzog hoped to do. Operate the trading post. Following this excerpt is some conjecture about who the Park Service would get to run the trading post, but the portion of the testimony quoted here is the part that committed the Park Service to a "live" trading post.

Bob Utley has stated that George Hartzog had been thinking about the "living history" concept for some time and that Hubbell Trading Post gave him a chance to create a place that was not just a "dead embalmed historic site." Utley thinks, too, that Hubbell Trading Post may have given impetus to the living history program throughout the Park Service. The idea appeared to work so well at Hubbell Trading Post that "... [Hartzog] plunged the Park Service into quagmires of 'living history'." [50] To that extent, then, Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site has historic significance within the Park Service itself. As for Bob Utley, he fought back against much of the living history program, feeling that "...it perpetuated all manner of inappropriate excesses on our interpretation of historic properties. [But] I have to concede that Hubbell Trading Post is the one place where it has really worked perfectly." [51]

But if June 21, 1965, turned out to be a lucky day for Hubbell Trading Post, it turned out to be a hard one for Robert M. Utley, Chief Historian for the National Park Service. He had seen a lot of the art and artifacts at the trading post, and when it came his turn to testify before the Subcommittee to tell the Congressmen about the richness of the collection at the trading post, he was met by some sharp questions from Senator Clinton Anderson, of New Mexico. It became apparent that the "expert" on Indian art and artifacts at the Hearings was Clinton Anderson, not Robert Utley. Utley was "subjected...to awful humiliation." [52] The day was not without its casualty.

Success

Hubbell Trading Post passed successfully out of committee with unanimous approval. And just at this time a movement was going forward to have former President Herbert Hoover's birthplace set aside as a national historic site. A Grant Wood painting from 1931 shows a modest wood-frame house that is painted white. It is a two-story, rectangular house with a small front porch, its long side, the front, facing a narrow, tree-lined road. A one-story addition extends from the back of the house, and there is what looks like a privy and then a shed just out back. Behind the shed is a red barn. A narrow stream below a steep bank meanders by one side of the yard. White towels hang still on the clothesline behind the shed and chickens peck around over by the barn. A tall, slender young man stands in the yard waving toward the viewer. A late afternoon sun slants the shadows long toward the southeast. If one can trust the state of trees, it is probably early autumn. The viewer looks down on the house, so possibly Grant Wood painted it from the top of a hill. As luck would have it, this bucolic scene is at West Branch, Iowa. Herbert Clark Hoover had the grace to be born there, and Representative Harold Gross was mighty interested that the native son's old house should become a national historic site. The boys from Arizona were content that he should have his way. Opposition to Hubbell Trading Post in the House was neutralized. The Hubbell Trading Post bill passed by a voice vote in the House on July 13, 1965. [53]

But just as the road was cleared through the House, Senator Clinton P. Anderson, of New Mexico, raised unneighborly objections to the trading post in the Senate. The $169,000 for 160 acres and some "pretty ramshackle" buildings seemed to him a steep price. [54] As Bob Utley had discovered, Senator Anderson knew a lot more than the average senator might about Indian arts and crafts and trading posts. And rumor had it that either Anderson himself or a friend of his had been taken advantage of in the purchase of an Indian blanket collection. [55] Morris Udall wrote to Senator Anderson to explain that the art and artifacts were indeed of considerable value, [56] and a dealer in Indian arts and crafts in Albuquerque by the name of M. L. Woodward wrote to Senator Anderson to advise him that Dorothy Hubbell could realize far more money if she were to break up the collection. Woodward went on to explain that he knew the men who had appraised the collection and he assured the Senator that they were competent and reliable. [57] Possibly this assurance from somebody in his own state swayed the Senator. Whatever the case, the bill, H.R. 3320, passed the Senate Interior and Insular Affairs Committee on August 12, 1965. The bill was voted on favorably in the Senate on August 17, 1965, and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the matter into law on August 28, 1965. Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site is authorized by Public Law 89-148. A total of $952,000 was authorized for the purchase of the land, the buildings, the contents of the buildings, and for development of the new historic site.

President Johnson gave the pen with which the bill was signed to Arizona's Representative Morris K. Udall. Udall wondered what he should do with the pen. In a letter to Ned Danson he said, "I was even thinking that maybe I might give it to you because it was your push and initiative that kept me from getting discouraged and giving up." [58] Ned Danson was spending six weeks in Europe, but Watson Smith, the Acting Director of the Museum of Northern Arizona, wrote to Morris Udall to tell him how satisfied he was that the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site was at last a fact. Ned Danson would be back in Flagstaff about the 16th of September, and Mr. Udall would surely hear from him shortly after his return. [59] Ned Danson wrote to Carl Hayden on the 17th of September, 1965. "It has taken eight years of work, but I think future generations will thank you and all involved." [60]

It still remained for the Park Service to negotiate a settlement with the Hubbell family.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

hutr/adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 28-Aug-2006