|

MEANINGFUL INTERPRETATION How To Connect Hearts And Minds To Places, Objects, And Other Resources |

|

|

"WE ARE OBLIGED BY THE DEEPEST DRIVES OF THE HUMAN SPIRIT TO MAKE OURSELVES MORE THAN ANIMATED DUST, AND WE MUST HAVE A STORY TO TELL ABOUT WHERE WE CAME FROM, AND WHY WE ARE HERE." —E.O. Wilson

|

SOMETHING SIGNIFICANT

Journal Questions:

Do you use interpretive theme statements or only when a supervisor asks for one? If you've never developed a product, ask some of your colleagues who have.

Do they help? Why or why not?

Do you find interpretive theme statements helpful? Why or why not? |

|

"Usually when a supervisor asks." |

|

"Sometimes theme statements are helpful. Some subjects easily lend themselves to themes, others don't." |

|

"Sometimes I have to work hard to develop a theme statement but the effort is definitely worth it. A theme statement helps me avoid the firehose effect." |

|

"Yes. I use a theme statement to direct my program. A theme statement allows the program to have a focus without needing a script. This way the audience can adjust my programs. I can respond to their individual needs while maintaining the program's direction in support of the theme." |

|

"I use themes regularly. They focus the product and process and keep me on track." |

|

"They help a lot! It's much easier to follow a focused story with a few relevant ideas than six or seven ideas that skip around disjointedly covering numerous subjects." |

|

"I don't use theme statements all the time. I am moving more and more into multiple, interwoven subthemes, exploring areas of diversity. I think subthemes might help make more connections for more people." |

| ASSIGNMENT |

|

See Part 9, Something Significant of the video and/or read Section Eight of the text, An Interpretive Dialogue. Also read Interpretive Themes: Saying Something Significant. |

An Interpretive Theme Statement

Creating an interpretive theme statement can be a critical step in the development of an effective interpretive product (See The Interpretive Process Model). An interpretive theme says something significant about the resource by connecting a tangible resource to an intangible meaning. The most compelling and relevant interpretive themes — therefore usually the most compelling and relevant interpretive programs — link a tangible resource to a universal concept.

|

"BUT WHEN THE INFORMATION WE PRESENT IS THEMATIC — THAT IS, WHEN IT'S ALL RELATED TO SOME KEY IDEA OR CENTRAL MESSAGE — IT BECOMES EASIER TO FOLLOW AND MORE MEANINGFUL TO PEOPLE." —Sam H. Ham

|

Questions

Are these interpretive theme statements? Do they link a tangible resource to at least one intangible meaning? Are they potentially powerful theme statements?

Do they link a tangible resource to a universal concept?

Examples

The endangered California condor represents the hope for, and survival of, wild places and species.

Fort Matanzas represents a juxtaposition between the global power and wealth of the Spanish Empire and the creativity and determination of local peoples protecting their land.

The amazing and strange saguaro is both a barometer of the health of the desert and a fragile victim of human errors.

The lost "Cittie of Ralegh" illustrates how a dream does not equal survival.

The surrender flags at Appomattox represent both the conflict of war as well as the ideals of both sides.

The Macaw Petroglyph at Boca Negra Canyon represents the importance of the bird to the rich ceremonial life of Puebloan peoples, both past and present.

Drilling for gas and oil in Padre Island National Seashore represents conflict between progress and preservation.

One of the greatest attributes of interpretive theme statements is the architecture they provide an interpretive product. When organizing a program around a theme that links a tangible resource to a universal concept, an interpreter must develop tangible/intangible links into opportunities for connections to resource meanings. Those opportunities must be intentionally sequenced to elaborate the theme's idea. Each opportunity builds on previous opportunities and provides the audience a chance to learn or feel differently. The effect of the arrangement is cumulative and articulates and explores the meaning of the interpretive theme statement.

|

"IDEAS WON'T KEEP; SOMETHING MUST BE DONE ABOUT THEM." —Alfred North Whitehead

|

SANDSTONE RIDGE, CATAWBA MOUNTAIN: PHOTOGRAPHER: DANIEL R.

SMITH

Journal Questions:

Do you intentionally arrange opportunities for connections to meanings or do you primarily rely on chronology or a series of related facts? Give an example.

Does your organization of opportunities support your theme statement? Give an example.

AN IDEA COHESIVELY DEVELOPED

INTERPRETIVE THEME STATEMENT

|

COHESIVE DEVELOPMENT OF A RELEVANT IDEA OR IDEAS

|

AUDIENCE CONNECTIONS

|

The following is a transcript of a short interpretive talk. As you read, imagine an interpreter holding and pointing to different parts of an old rifle.

The Gun Talk

This is a model 1841 Harpers Ferry Percussion Rifle. In the 1840s, it represents the very essence of modern times.

It does so for technological reasons. This weapon is made entirely by machine and entirely with interchangeable parts. It loads from the muzzle and is a rifle, meaning there are spiral grooves cut into the barrel that send the ball out with a spiral — just like a correctly thrown football — which gives the weapon great accuracy.

The 1841 Harpers Ferry Percussion Rifle fires with a percussion system, meaning there is no flint and steel, no spark or flash outside the weapon as there was with the preceding flintlock system. The hammer of this rifle strikes a small percussion cap, shaped like Abraham Lincoln's top hat. A bead of explosive located in the top of the brass cap ignites when hit, which begins the process that sends the bullet on its way.

DRAWING OF RIFLE FACTORY: HISTORIC PHOTO COLLECTION, HARPERS

FERRY NHP

I like to think about the human hands that made this rifle because the weapon also represents modern living. Sometimes I imagine the parlor of a worker. I think of him living with a large family that includes his father. I like to listen to their conversations.

In my mind, the father says "Son, you have lost the meaning of 1776. I was a craftsman. I spent eight years of my life working as an apprentice to gain the knowledge and skill needed to make an entire weapon with hand tools. I owned those tools. If I did not like the way I was treated in the factory, I could move away and set up a gun shop anywhere. I had freedom. I controlled my own destiny. I was proud.

"But you, son, in your wildest dreams you will never own the machines it takes to make a rifle now. The day the men who own those machines decide they no longer need you, you'll be lost. You are a slave to those machines, not a free man."

The son responds, "But I'm making more money than you ever did. Our home is made of brick with smooth plaster walls. The house we lived in before was log, and washed away in the last flood. Our house has carpet, and my daughters go to school. I own books and buy newspapers. You could only afford to buy us things we needed to stay alive. No Father, I understand what 1776 was about and the money that flows out of that gun factory and into my pocket buys more freedom than you could ever afford?'

Of course the two never come to understand one another. But this weapon represents their lives and the way they viewed the world. It might represent the clash between the past and the present. We can ponder this rifle, an object made of cold metal and dead wood, and ask how in our own time we respond to their same challenge — the conflict between tradition and change?

THE GUN TALK BROKEN DOWN

INTERPRETIVE THEME STATEMENT

|

|

IDEA COHESIVELY DEVELOPED

Sequenced opportunities for connection to meanings: Opportunity One — The rifle represents modern times for technological reasons. This opportunity for intellectual connections offers insight and is developed through examples and description. Opportunity Two — The rifle represents the craftsmen's perspective and tradition. This is both an intellectual and an emotional opportunity meant to provide understanding of and empathy toward the craftsmen's world view. The opportunity is developed with the interpretive methods of anecdote, personification, and presentation of evidence. Opportunity Three — The rifle represents the machine-age perspective and change. This is both an intellectual and an emotional opportunity meant to provide understanding of, and empathy toward, the machine-age world view. The opportunity is developed with the interpretive methods of anecdote, personification, and presentation of evidence. Opportunity Four — The rifle represents conflict between past and present or tradition and change. This opportunity is both intellectual and emotional. It attempts to provoke insight about conflict during the Industrial Revolution as well as empathy for those who experienced the conflict. Placing the previous two opportunities next to each other — in conflict — largely developed this opportunity but it was also directly articulated in the last paragraph. Opportunity Five — This rifle might mean something to you. Primarily intended to be an emotional opportunity and provoke the audience to feel the rifle has symbolic value, the opportunity is developed through a rhetorical question. |

|

POSSIBLE AUDIENCE CONNECTION

"The program was about how technology changed and how some people liked it and others didn't. Sort of like today." |

The opportunities for connection to meanings, both emotional and intellectual, presented in the Gun Talk cohesively develop a relevant idea. These opportunities for connection are purposely sequenced to explore the interpretive theme statement.

Opportunity

1. ESTABLISHED THE EXISTENCE OF TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE

2. ESTABLISHED THE PREFERENCE OF SOME FOR TRADITION AND RESISTANCE TO SOCIAL CHANGE

3. ESTABLISHED THE ACCEPTANCE OF CHANGE BY SOME PEOPLE AND THEIR EAGER EMBRACE OF SOCIAL AND MATERIAL CHANGE

4. ESTABLISHED THE CONFLICT BETWEEN THOSE WHO HOLD TO TRADITION AND THOSE WHO ACCEPT CHANGE

5. EMPHASIZES THE SYMBOLIC POWER OF THE RESOURCE AND ENCOURAGES THE AUDIENCE TO CONSIDER TRADITION AND CHANGE IN THEIR OWN LIVES

Audiences might recognize and connect with many meanings not listed or described in this analysis of the Gun Talk. Audiences bring their own personalities to any interpretive program or service and make connections in a personal and subjective way. That is to be expected and encouraged. The previous and following strategies for identifying the cohesive development of a relevant idea attempt to describe the interpreter's intent to help audiences make their own connections.

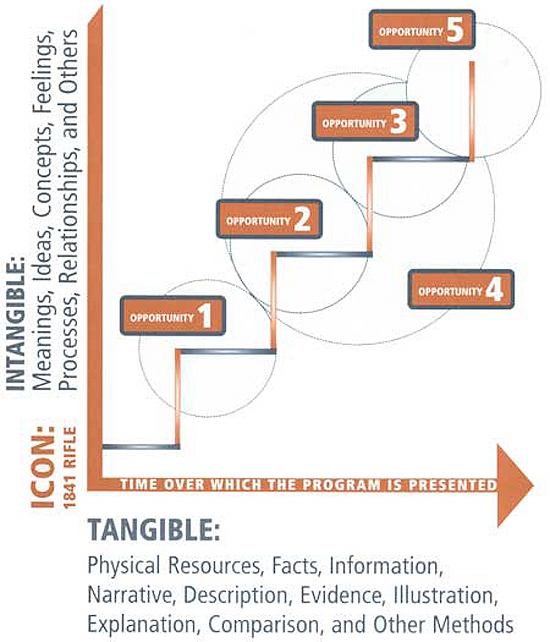

Another Way of Looking at It

The following is another representation of how the interpretive theme statement provides architecture for the Gun Talk. This visual metaphor illustrates the program's tangible/intangible links, opportunities for connection to meanings, and the sequence of opportunities that cohesively develops the idea articulated in the interpretive theme statement.

Key

The program begins with a blue-gray horizontal line that represents the information presented in the first sentence — a statement of fact.

OPPORTUNITY ONE

The first tangible/intangible link is indicated on

the graph by the first vertical rust-colored line. This line represents

the weapon's relationship to the meaning of modern times. By itself, the

link is not an opportunity for connection to meaning. An opportunity is

a link developed by some interpretive method or technique. The blue line

at Opportunity One represents examples and description used to develop

the link into an opportunity for an intellectual connection to the

rifle's meanings. The opportunity's intent is to provide insight and

understanding as to how the weapon was made, functioned, and represented

modern technology. Notice, the blue line here is long. Much time and

explanation was invested in this opportunity relative to the entire

program.

OPPORTUNITY TWO

The second link developed into an opportunity is

indicated with the second rust colored line — the rifle linked to

craftsmanship and tradition. The blue-gray line paired with it at

Opportunity Two indicates the methods of anecdote, personification, and

evidence presentation used to provide both intellectual and emotional

opportunities to connect with the rifle's meanings. The opportunity

provides insight into the craftsman's world view as well as provoking

empathy for that view.

OPPORTUNITY THREE

The rifle is linked to the machine-age and change.

Here again the methods of anecdote, personification, and evidence

presentation provide both intellectual and emotional opportunities

similar to those of Opportunity Two.

OPPORTUNITY FOUR

This opportunity is the result of cumulative effect

— the purposeful juxtaposition of Opportunities Two and Three and

the fictional relationship between father and son. The two world views

are obviously in conflict and made more acute by being in a family

setting. The opportunity reveals conflict brought about by the

Industrial Revolution as well as provokes empathy for those who

experienced it.

OPPORTUNITY FIVE

The final intended opportunity links the rifle's

meanings directly to the audience with a rhetorical question. This

opportunity is primarily emotional and meant to inspire a sense of value

and personal meaning.

THE COHESIVE DEVELOPMENT OF A RELEVANT IDEA OR IDEAS

The whole graph, the combination and arrangement of

each stair step or opportunities for connection to meanings, supports

and illustrates the idea articulated in the interpretive theme

statement.

THE GUN TALK GRAPH

INTERPRETIVE THEME STATEMENT

|

EXAMPLE

"Tradition and Transformation"

Michele Simmons, National Park Service

TLINGIT TOTEM POLE, MSCUA, UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON LIBRARIES #NA 2708 |

Though change is constant in human experience, it's rarely embraced. Change can be uncomfortable or frightening whether it is as personal as aging or as cultural as the sudden interaction of two age-old civilizations.

The native peoples of Southeast Alaska have dealt with many changes both before and after foreigners first entered their lands. Though the Southeast cultures value long-established tradition and highly formalized protocol, elements of their lifeways provide insight into the nature of change in all life. In fact, the totem poles displayed in Sitka National Historical Park, well-known symbols of Southeast Alaska Indian culture, speak of rebirth following change.

The life of a totem pole begins with a particularly difficult form of change — death. Carving a pole requires cutting a tree, usually a cedar. Southeast cultures hold that objects in the natural world have their own spirit. Consequently, a tree's life is taken with utmost respect. Songs ring with dignity and speeches praise and thank the tree for its sacrifice. Only then is the tree cut.

The tree's death, while it may seem final, is really the beginning of a dramatic transformation. Day by day, a master carver wielding an axe carefully removes chips of wood to coax images of animals, people, and mythical creatures from the tree. The carver is highly paid for his skill. After several months the change is nearly complete. A finely crafted totem pole is ready for placement.

The raising and dedication of a new totem pole occasions another dramatic change. Again with much fanfare, ceremony, and protocol, the pole rises in its place. During the ceremony, however, a fundamental transformation occurs. Once dedicated, the pole is no longer an expensive, commissioned object. Rather, it is living totem pole, infused with its own spirit, sometimes represented by a spirit face in the design. When asked how much a particular pole was worth, one modern Tlingit responded, "How can you put a price on a life? It is priceless?"

Like the cedar tree, the Southeast Alaska peoples have seen times of change that sometimes appeared dismal. Not long ago, the practice of totem pole carving was in danger of being lost as master carvers died without the opportunity to pass on their skills. Recently, however, there has been a rebirth of the art of totem pole carving as well as many other aspects of Southeast culture.

The Southeast Alaska Indian Cultural Center is one organization fostering native arts and providing a place where master craftspeople can teach their skills to the next generation of artisans. Located in the Visitor Center of Sitka National Historical Park, the cultural center also provides an opportunity for visitors to watch, interact with, and be inspired by these local artists. There, master carvers like Tommy Joseph still pass on the craft of totem pole carving, creating new poles that can remind us all that change, even frightening change, can be transforming.

What tangibles did the essay use?

What icon acted as the vehicle?

What intangible meanings were present?

Were there any universal concepts?

Did the essay have a focus? Was it a cohesively developed idea or ideas? If so, what idea or ideas?

Example

TANGIBLE

Totem poles, people of southeast cultures, Sitka National Historical Park

ICON

Totem poles

INTANGIBLE MEANINGS

Life, death, change, craftsmanship, skill, preservation, how Tlingit

people create totem poles, value, worth, spirit

UNIVERSAL CONCEPT

Life, death, change, spirit

IDEA COHESIVELY DEVELOPED

The totem poles at Sitka National Historical Park speak to life after

death — the rebirth that follows change.

Sample Analysis

First and Second Paragraphs

The explanation delivery method provides opportunity for insight into the universal concept of change. Few people embrace change, but the totem poles at Sitka help us reflect on it.

Third and Fourth Paragraphs

Explanation and description delivery methods focus on death through the process of creating a totem pole while a cedar is respectfully sacrificed and a form is carved.

Fifth Paragraph

Again explanation along with a quote and question provides an opportunity for understanding the spirit or new life inhabiting the totem pole. There is also opportunity for readers to feel inspired, hopeful, and renewed at the cycle of life following death.

Sixth and Seventh Paragraphs

Explanation again provides the reader with insight regarding how Southeast Alaskan cultures adapted to change and are able to preserve the craft and its meanings. Also, opportunities for inspiration, hope, and renewal are reinforced by tying the craft with analogy to all change and the possibilities for transformation.

| EXERCISE |

Read The Interpretive Analysis Model. Apply its methods of analysis to interpretive writing examples on pages 93, 98, 103, 107, 132, 136, and 138. |

|

"IF YOU HAVE A MESSAGE — SEND A TELEGRAM." —Samuel Goldwyn

|

Not the Moral of the Story

It's important to realize that interpretive theme statements are not take-home messasges. Audiences don't have to parrot the product's interpretive theme statement for the product to successfully convey a meaningful idea or ideas. Because the audience's connections with the meanings of the resource are personal, the idea or ideas they take from a finely crafted interpretive product may vary widely. The product is successful to the degree it helps audience members make connections.

RES LOQUITOR

Sunni Mercer, National Park Service

PAINTING OF SAINT-GAUDENS BY KENYON COX, 1908 |

Latin Meaning: The thing speaks for itself.

Res Loquitor, a term used frequently in law, refers to the intrinsic value of an object as evidence.

In art, artists define this phrase as, the point at which the viewer makes a connection with the object, and reaches an understanding or a feeling. It is an ah ha moment for the viewer. When a thing reaches Res ipsa, the hand of the artist or interpreter is no longer important. The object is often so powerful that the creator disappears. The viewer at this point begins a personal dialogue with the object. The great photographer Alfred Steiglitz coined the term equivalence to mean basically the same thing. Here the artist's intent is secondary to the image's ability to evoke a feeling unique for each viewer. What the artist wants to say is important, but ultimate success comes when the viewer connects the message with his or her own experience.

|

"WHAT STRIKES THE SPECTATOR IS NOT NECESSARILY WHAT STRUCK THE CREATOR. THEY REACT ON TWO LEVELS; THE ARTIST TO HIS SUBJECT, THE SPECTATOR TO THE ARTIST. —William Markiewicz

|

| EXERCISE |

Use your lists of tangibles, intangible meanings, and universal concepts to draft an interpretive theme statement. Check it against the interpretive theme definition in Interpretive Themes: Saying Something Meaningful. Arrange a series of opportunities for connections to the meanings of the resource that support your theme. Some of those opportunities should provide opportunities for emotional connections and some for intellectual connections to the meanings of the resource. |

|

"THE THEMES ARE TIMELESS, AND THE INFLECTION IS TO THE CULTURE." —Joseph Campbell

|

| EXERCISE |

Read Sections Six, Seven, and Eight of the text, An Interpretive Dialogue. Graph one of your existing interpretive programs. What is the tangible resource you link to resource meanings? What theme statement do your opportunities for connections to meanings support? Which opportunities encourage emotional connections and which provoke intellectual connections to the meanings of the resource? Have one or more of your colleagues attend and graph your program. Compare your graph, your theme statement and the opportunities you offered to their graph. Use the graph as a tool to analyze and develop interpretive products and media. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

meaningful_interpretation/mi6k.htm

Last Updated: 29-May-2008

Meaningful Interpretation

©2003, Eastern National

All rights reserved by Eastern National. Material from this electronic edition published by Eastern National may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of Eastern National.