|

MEANINGFUL INTERPRETATION How To Connect Hearts And Minds To Places, Objects, And Other Resources |

|

|

"IF SOMETHING COMES TO LIFE IN OTHERS BECAUSE OF YOU, THEN YOU HAVE MADE AN APPROACH TO IMMORALITY." —Norman Cousins

|

INFLUENCE AND POWER

Journal Questions:

Do you have memories of being inspired by an interpreter, docent, ranger, guide, teacher, or camp counselor? Who was it and how did they effect the way you view environmental and historical resources?

Have you heard your colleagues describe such influences?

Recall professional experiences where a child or an adult connected with you in a special way? Describe one or two.

|

"I AM DONE WITH GREAT THINGS AND BIG THINGS, GREAT INSTITUTIONS AND BIG SUCCESS, AND I AM FOR THOSE TINY INVISIBLE MORAL FORCES THAT WORK FROM INDIVIDUAL TO INDIVIDUAL BY CREEPING THROUGH THE CRANNIES OF THE WORLD LIKE SO MANY ROOTLETS, OR LIKE THE CAPILLARY OOZING OF WATER, YET WHICH, IF YOU GIVE THEM TIME, WILL REND THE HARDEST MONUMENTS OF MAN'S PRIDE." —William James

|

Journal Questions:

How often do visitors ask you how you got your job or what it's like to do your work? What do you think is behind their questions?

How often do visitors ask you how you got your job or what it's like to do your work? |

|

"They're envious! They want to know how I got a job doing vacation stuff." |

|

"They find what I do an inspired, interesting, and honest profession." |

|

"Maybe they're unsatisfied with their jobs and romanticize ours." |

|

"They want to learn whether the job's magic is what they imagine, and consider choices they've made in their careers." |

|

"I think they're trying to make a deeper connection to the resource and want to get an insider's view." |

|

"Some think we don't really work and are roving around doing what we want." |

|

"They are curious about a brand of people that want to be outside in hot clothing and have to repeat the same answers to the same questions. I am just glad they engage me; most don't." |

Filling the Gap

Dave Dahlen, National Park Service

Part 1

Moving through the forest along the ridge line, I feel a growing sense of anticipation. The fall air is clear and the sky above the tree-tops offers brilliant flashes amidst autumn colors and a faint smell of wood smoke. Then I see it, a mountain gap with walls so sheer it takes my breath away. I marvel at the geology revealed in its weathered cliffs and the vivid colors of the eastern hardwood forest in peak display.

Today is special. It's the culminating moment of years of hard work by dedicated people to protect this particular place from interstate progress. In the distance, hammered-dulcimer music vibrates through the trees, setting the stage for those who worked so hard to preserve the rich diversity found within this gap's many climates.

Speeches rouse, credit is shared, and smiles abound. Thoughts center on beauty, solitude, heritage, legacy, and accomplishment — big ideas joined in one grand preservation effort. As the dulcimer fades into memory, I reflect, how did it happen? Why did people believe such preservation could be? What value in this small but spectacular slice in the landscape?

Later, driving near that protected reservation, the purpose and point of it all crashes into my consciousness as I pass through another gap in a mountainside. This gap, equally abrupt, carved by human force, contains four lanes of paved expediency. The irony gives me pause.

APPALACHIAN TRAIL: LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS

DIVISION

PROFESSIONALISM

Through the years many voices built our interpretive foundations. Contributors too numerous to mention, were each important. Significant milestones center around John Muir, Enos Mills, and Freeman Tilden. Many others built on their foundations: Rachel Carson, Bill Lewis, and Sam Ham. Each brought new elements to this complex craft we call interpretation. Something lived in their words, words that elaborated formative concepts, served the needs and issues of their day, and contributed ideas and explanations that benefited all.

In their 1988 National Association for Interpretation (NAI) presentation, Bill Sontag and Tom Haraden ("Gotta Move! We've Outgrown the House: A Discussion Forum on Interpretive Professionalism," Workshop Proceedings, NAI, 10/88) stated that interpretive professionalism needed definition. Careful study of professions, they said, yielded common factors that would benefit interpretation.

Elements of professionalism existed within the interpretive rank and file, but a common understanding of how the craft should be anchored as a profession proved elusive. Among the elements proposed for a solid interpretive foundation were: an articulated philosophy, common terminology, standards of practice, evaluation, and monitoring.

Do you aspire to be an interpretive professional? What do you set as your personal standard of professionalism? I suspect that most of us would quickly concur that interpretation is a profession. An equal number would defend their role as professionals. How many have truly pursued the meaning of that term?

Some interpreters appreciate the ambiguity as permitting flexibility in delivery and adaptability to certain audience types. Ambiguity also allows a personal freedom and independence to do interpretation as they wish. Without a focused purpose, many different tools and tricks of the trade can be applied at the interpreter's whim.

This is not necessarily a bad thing, except when point, purpose, and audiences' personal connections with the resource are lost. When such unfocused interpretation happens it extends negative perceptions of the craft as a non-profession without specific organizational goals.

Nature centers, state and local parks, national forests and parks, historic sites, and refuges need as many supporters and advocates as they can muster. Likewise, those advocates must believe in and be committed, for their own reasons, to the site's mission and goals. Interpreters need sophistication to summon their personal passion and apply it in well developed programs, prompting the audience to form their own passion for the resource. This places an obligation on each of us to develop our professionalism to its highest possible level. The places deserve that. Those who hear your stories deserve that. A professional approach to interpretation creates relevance as a shining by-product of your work.

|

"THE ONLY TRUE DEVELOPMENT IN AMERICAN RECREATIONAL RESOURCES IS THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE PERCEPTIVE FACULTY IN AMERICANS. ALL OTHER ACTS WE GRACE BY THAT NAME ARE, AT BEST, ATTEMPTS TO RETARD OR MASK THE PROCESS OF DILUTION." —Aldo Leopold

|

Journal Questions:

Do you consider interpretation a profession? Why or why not?

Do you consider interpretation a profession? Why or why not? |

|

"Yes!! It may seem anyone can get up and provide information, but there is a real art to do it well and provide value to the refuge." |

|

"If a profession is defined as an occupation requiring considerable training, specialized study, constant growth, change, and evaluation to remain viable and relevant, I have to argue that interpretation is definitely a profession." |

|

"Enos Mills compared interpretation to the professions of engineers, lawyers, and doctors. 'Ere long nature guiding [interpretation] will be an occupation of honor and distinction. May the tribe increase!'" (from Adventures of a Nature Guide, 1920, Enos Mills) |

|

"Yes. Interpretation has a professional organization with regional and national workshops every year; the professional organization sponsors a general publication and research publication in which interpreters present new ideas and concepts; it has standards that can be peer reviewed and certified; it has an academic wing with formal degrees granted to the level of Ph.D; and it has extensive literature, both books and articles." |

|

"Professional interpretation is similar to professional artistry; requiring a deeply nurtured passion and the continued practice and refinement of the art form or craft. Professional implies not only the continued development of the individual, but also the continual sharing and enrichment of the art-form through collaboration and group interactions." |

|

"I think a profession includes a belief or sense of mission regarding the work as well as a dedication to the refinement, improvement, and advancement of the field. Successful interpreters have that." |

|

"Those who rest on their laurels, their first set of finely honed skills, who don't believe that their knowledge and skills need constant upkeep, upgrades, and updates, may find it hardest to see interpretation as a profession." |

What Makes a Profession?

Public service with Social responsibility

Foundation of knowledge — research based

Specialized education and training

Responsibility of practitioners for application of standards

Programs of accreditation and certification

Established codes of ethics

Life-long learning

—Lisa Brochu and Tim Merriman, Personal Interpretation:

Connecting Your Audience to Heritage Resources, p. 3

| ASSIGNMENT |

|

See Part 10 Influence and Power of the video or read Section Ten of the text, An Interpretive Dialogue. |

|

"A TEACHER AFFECTS ETERNITY; HE CAN NEVER TELL WHERE HIS INFLUENCE STOPS." —Henry Brook Adams

|

Making a Difference

Constantine J. Dillon, National Park Service

Too often our jobs become routine. We see the same buildings and scenery every day that visitors may see only once. Our familiarity with our jobs and the exceptional places we work can lead to a blasé attitude. We forget our actions can have great effect on a visitor's experience. I found this to be true early in my career.

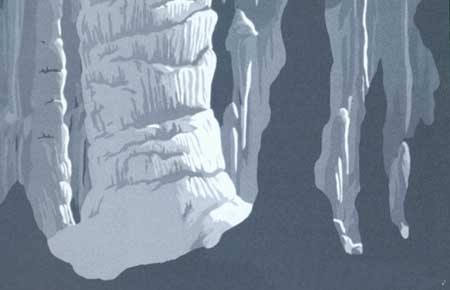

Years ago I was one of the many cave rangers that patrolled the asphalt trails of Carlsbad Cavern. Every day, eight hours a day, we walked against the one-way pedestrian traffic on the cave's trail. Visitors, ears glued to the audio-loop listening devices, often ignored live rangers. Many rangers thought themselves superfluous, and the job boring and meaningless. Yet, people like to connect to people, and rangers always know more than a recording. It was up to us to entice the visitor away from the recorded voice.

One method offered to show visitors formations that the recording did not include. We would take our flashlights and highlight cave features that were outside the electric lighting or too small to otherwise notice. One day, for no particularly reason, I chose to pick out a family of an older man, younger couple, and what looked like the oldest man's grandchildren, who were patiently walking the trail and listening to the recording.

"Would you like to see something neat?" I asked. When they responded I proceeded to point out a variety of interesting formations along the trail and talked about how they formed. They were attentive and appreciative. They thanked me and walked on. An hour or so later I came upon this group again, something that often happened because of our practice to walk the one-way trail in the opposite direction. They recognized me and asked if there was anything I could show them in that area.

Excited to be doing real interpretation, I eagerly pointed out more formations, talked about the cave's history, answered their questions, and generally had a good time making their visit a little more interesting. Again, they thanked me and moved on. I thought no more of the encounter than I did with hundreds of other visitors on those busy summer days. Yet, this turned out to be something more.

Not more than an hour later I was heading to the cave's underground lunchroom and the elevators that would take me to the surface.

WORK PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION

POSTER COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND

PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION

I spotted the family having lunch and went over. They greeted me with enthusiasm and told me what a great time they'd had. Finally, the older man gave me his thoughts. "You know," he said, "we live in El Paso and I have been through this cave many times over the years, but I have never had as good a time as today."

That certainly made me smile! He continued, "You showed me things I had never noticed before and made this the best trip through the cave I've ever had." If he had stopped right there I would have left pleased with myself. But then, he added, "What made this walk so meaningful," he continued, "is that next week I am going to have my legs amputated because of a circulation problem, and I will never be able to walk through this cave, or anywhere else again."

I will never know what made me pick that family. I was more than glad the cave was dark and it was time for my lunch because the tears welling in my eyes and the sinking feeling in my stomach made it impossible for me to go back to work immediately.

I have had a lot of great experience in my 22 years with the National Park Service, but none has meant more to me than this one. You never know when you will make a difference. We work in the nation's most magnificent places, and when we do our job well, we make that magnificence more meaningful for visitors.

|

"REAL GENEROSITY TOWARDS THE FUTURE LIES IN GIVING ALL TO THE PRESENT." —Albert Camus

|

Being a Professional

There are three chief elements for success in the craft of interpretation,

1) Knowledge of the Resource;

2) Knowledge of the Audience; and,

3) Appropriate Technique. Each requires great personal investment.

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE RANGER, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE |

Knowledge of the Resource

There are no shortcuts for knowing the meanings of the resource. The audience that is informed about the place will find an interpretive program superficial and incorrect unless it is based on a graduate-level knowledge — no matter how skillful the presentation. A comprehensive, up-to-date knowledge of the site and its broadest contexts is a never-ending responsibility. Extensive knowledge of the resource acts as a reservoir of relevance that allows an interpreter to meet audiences with meanings that interest them, then provoke exploration of additional meanings.

Knowledge of the Audience

All connections to the meanings of the resource happen within the audience. This means that all successful interpretation begins at a point that is relevant to them. Without an understanding of what the resource means to the visitor, the content and delivery of an interpretive product is merely a guess. It will work for those who happen to agree, but miss too many others. Learning about the audience requires good listening, an open mind, the ability to recognize change, and research skills.

|

"DO NOT WAIT FOR LEADERS; DO IT ALONE, PERSON TO PERSON." —Mother Teresa

|

Appropriate Technique

Without a mastery of the specific skills required by each of the many interpretive techniques and competencies — talks, tours, interpretive writing, etc. — an interpreter has limited ability to facilitate a connection between the meanings of the resource and the interests of the audience. Opportunities for connections to resource meanings come from tangible/intangible links developed with interpretive delivery methods. These skills allow the interpreter to communicate meanings. Such skills take self-evaluation, peer-evaluation, audience input, a great deal of practice, and time.

| EXERCISE |

Read The Interpretive Equation: More Than the Sum of Its Parts. Use the Interpretive Equation to analyze your products, sample products in this book, or other interpretive products. |

|

"THE GREATEST THING A HUMAN SOUL EVER DOES IN THIS WORLD IS TO SEE SOMETHING, AND TELL WHAT IT SAW... TO SEE CLEARLY IS POETRY, PHILOSOPHY, AND RELIGION — ALL IN ONE." —John Ruskin

|

Filling the Gap

Dave Dahlen, National Park Service

Part 2

Adding Your Voice

An additional challenge of professionalism is to have a well-grounded concept of the work at hand. What is the ultimate purpose of our work? Protect resources? Enlighten the public? Provide alternative uses for fragile environments? Educate children? All of the above?

A starting point is the voices that spoke so eloquently when building the foundation we work from. Our profession is varied, and to be professional one must know as many opinions and perspectives on the craft as possible. Read. Study the resources and your profession. What do your predecessors and peers say? What value can you discover in interpretation for your personal vision for the work you do? During your study, ask yourself, "What do I want to add to that line of voices? Does my vision match my organization's?"

WORK PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION

POSTER COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND

PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION

Part of being professional is having direction and purpose. Once you've established a solid foundation in the profession, you are a free-agent. You can articulate what you want to accomplish and are aware of your skills. To be sure, many factors affect how and where you practice your profession.

But ranking high on that list should be what you want to accomplish and how you can do that in the context of your organization. If there is conflict there, be aware of it and manage your options as far as your circumstances allow. In the end, your professionalism will speak volumes about you and the work you do. Professionalism will provide the guiding light to accomplish what you hope to achieve.

The ultimate purpose of our work has been, and long will be, debated.

"Entertain the visitors! Send them home happy!" Some feel the immediate protection of resources is paramount. Others argue that knowing our heritage allows us to make better decisions for the common good. Still others suggest that the tangible resources we work with today are transitory, and that what we are really trying to do is sow the seeds of ideas and ethics (about the land and about ourselves as a society). If so, hopefully these seeds will grow and have a cumulative effect over time. That should lead to a better balance between cultures, and between humans and our planet for a real long-term effect — forever.

Addressing these questions and developing your own personal foundation will entail a cost of time invested, money needed, and occasional personal sacrifice. Keep in mind that what you invest in the process yields corresponding dividends, sometimes multiplied. You must commit the time needed to read the interpretive pioneers and your contemporaries. You must invest time to take personal ownership of your career, charting both course needed and resources required to move toward your ideal of professionalism.

Seek out resources, training, and professional opinions, easily accessible as-well-as distant and obscure. You must engage in professional dialogue with your peers and colleagues on the principles, practices, and defined standards of interpretation. Agree with them; disagree with them; but explore and understand them. Avoid the pitfall of thinking you know it all, and embrace the diversity of ideas and opinions that you discover. ALL professions have as underlying tenets the need and practice of dialogue, exploration of concepts, and charting new courses. This is how those professions, including interpretation, will continue to grow.

WORK PROJECTS ADMINISTRATION

POSTER COLLECTION, LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, PRINTS AND

PHOTOGRAPHS DIVISION

You will also need to invest in professional organizations that relate to interpretation. The primary national group is the National Association for Interpretation, headquartered in Ft. Collins, Colorado. Join this and other similar groups as your personal resources allow. Annual meetings and regional workshops provide excellent opportunities to engage in professional discussions and see what others are doing in the field. There's no better energizer than to add your voice and hear those of others in the continuing growth in understanding interpretation.

A career in this profession might span 25-35-45 years, a remarkable contribution. When applied with passion, dedication, and heart, the cumulative effect can be astounding. But leaven this with a dash of reality. What we hope to hand down are seeds that grow into a cumulative positive effect — perpetuating all that is good and bad about ourselves, our cultures, our environments, and our species.

But in the grand scheme, 35 years is just a blip on the screen. All we can hope for is to leave our place a better place, contribute to our today with an eye on tomorrow, hope that we pass it along to those who come after, and spark their vision to carry on. In a sense, those voices that came before are now humbly joined by ours. We add our bit, and trust that if enough glue is applied we will make a contribution to forever.

For many of you the backdrop for your personal professional development is crafted by the organization for which you work. Many nature centers, private foundations, state, local and national agencies exist with a mission, or statement of purpose, that guides the management and public use of the resources we interpret. Most, if not all, of those organizations exist with fiscal limitations that often make it difficult to accomplish all the work that needs to be done.

Many interpreters are only "part-time" in that they have a myriad of additional duties to accomplish in their work-week. If quality time exists to develop and present a program, it's precious little, and often after hours. Once you establish your personal goals in this profession, a second key question faces you: How will you use your professional skills to fulfill the organization's mission or the mandate you work under?

Journal Questions:

Do you have influence and power? Why or why not?

Do you have influence and power? |

|

"If I didn't, it would be difficult to come to work." |

|

"I have respect and hold myself humble enough to wonder if I hold this power to influence." |

|

"Yes. Thousands of people, rich and poor, young and old, interested and bored, influential and ineffective, listen to me talk about what I like. Those people think, feel, talk, buy, and vote." |

|

"I can lead people towards a stewardship ethic, and that is incredibly powerful." |

|

"I believe it when I see friends or co-workers emulate my behavior." |

|

"Yes, and with it comes responsibility. Interpreters in public service have been given influence and power on behalf of the American people, and we are accountable to them to use this influence and power to further the common good." |

|

"Yes, now I do. This was a difficult concept for me to accept because of the responsibility that comes with it." |

|

"I am a tree spreading new seeds though wind, water, animals, etc. Hopefully a few will be planted and, with nurturing, will grow into trees as well...and the process continues..." |

|

"I wouldn't call it power. I'd call it an opportunity and a gift." |

|

"I have some influence over what information visitors get, but I don't see myself as having much power." |

Meeting Tilden for the First Time

Mike Watson, National Park Service

As a science education undergraduate at Ohio State University, I started out taking the harder sciences — chemistry and physics. Not wanting to drive my hometown Mr. Softee Ice Cream truck yet another summer, I landed a job as a naturalist at a 4-H Camp after my sophomore year. A local flora class I had just completed was all I needed to qualify. Discovering nature that summer, I turned to biology, botany, and zoology during my final years in college.

Before graduation, I knew I would be teaching eighth-grade science in a public school. When I saw a job notice on the Botany Department's bulletin board for summer naturalist positions with the Ohio State Park System, I called and made an appointment with the state's Chief Naturalist. He invited me for an interview, and I rode my bike three miles to the state Department of Natural Resources offices in downtown Columbus.

FREEMAN TILDEN ILLUSTRATION, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE |

The interview began with a written test. I remember how pleased I was to name five kinds of maple, seven types of oak, and five species of woodpeckers found in Ohio. Naming the five Circumpolar Constellations was a breeze, and I pointed out that the 40th parallel ran smack through campus, assuring that all five constellations were visible year round in the Columbus night sky.

The Chief Naturalist especially liked my answer to the question, "What is a hoop snake?" I wrote, "Never heard of it." The reason he was happy with that reply, of course, is that a hoop snake is an old wife's tale and my ignorance of such was an honest admission of lack of knowledge rather than an attempt to fake my way through an explanation.

I was hired on the spot and told that I would be the first naturalist at Burr Oak State Park in Southeastern Ohio, the unglaciated third of Ohio that makes a visit to the state worthwhile. The Chief Naturalist explained that all summer naturalists would have a couple days training before reporting to our jobs.

A day before my last final exam, I received a notice at the dorm about my summer job. It explained that the Chief Naturalist who hired me had taken a new job and introduced the new Chief who would conduct our training and oversee our programs. A personal letter from the new boss gave each of us an assignment — we were to read a book by one Freeman Tilden entitled Interpreting Our Heritage before showing up for training.

What a pain! I was just finishing finals and reading another book was not on my list of things to do. But I went to the main library and looked it up. There it was, only one copy of Interpreting Our Heritage on the entire Ohio State campus, housed at the Landscape Architecture Library I had no idea where the LA Library was, but finally tracked it down and rode my bike over after my last final.

It was May 1967. Undoubtedly the copy of Tilden I read in one sitting was an original 1957 copy, the one with the subtitle, Principles and Practices for Visitor Services in Parks, Museums, and Historic Places. I recall being moved by Tilden's definition of interpretation. I remember hand-copying Tilden's six principles into an unused blue book I planned to carry to the upcoming training and summer job. I began to realize that although related, being an interpreter was different than being a science teacher or naturalist.

My summer colleagues and I got together a week later to discuss Tilden's book with our new Chief. He challenged us to become interpretive naturalists. He made us outline our programs and incorporate ideas that employed Tilden's principles. I am eternally grateful to him for forcing me to discover Tilden. It was the first rewarding interpretation training program I attended.

I surprised a co-worker the other day when I confessed that I had never met Tilden personally or professionally. He could not believe that my training and career experiences in the National Park Service never allowed our paths to cross. But the day I sat relaxed in a strange library after finishing my final exams and my undergraduate education, I surely met Freeman Tilden through his seminal work.

Our meeting came at a time when I needed to fill a void with advice that would steer me in a new and proper direction. No longer could I be proud of or be satisfied with the simple naming of trees, birds, constellations, or hoop snakes. From that day forth, I would have to meet a higher standard of practice as a science teacher, a naturalist, an interpreter. I would have to convey relevance and provoke minds and avoid lists and rote recitations.

That's what it's been like ever since I first met Tilden.

| EXERCISE |

Read one or more of the following texts. Each author effected the profession, and the suggested titles represent fundamental reading for interpreters. All experienced interpreters should read each. If you've already done so, consider if and how each author influenced the way you do your work. Be specific. If a given author did not reach you, perhaps you should read that book again. |

Interpreting Our Heritage, Freeman Tilden, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1957.

Interpretation hasn't been the same since Tilden. Often described as the father of interpretive philosophy, Tilden effected every interpretive writer, thinker, and serious practitioner who came later. It is difficult to identify any idea or contribution to the field since 1957 that was not anticipated by this seminal work. Also see Robyn Dochterman, "Freeman Tilden: The Writer-Wanderer Who Showed us the Way," Legacy, 13 (May/June 2002): 16-25.

Adventures of a Nature Guide, Enos Mills, New Past Press, 1990.

Some say Tilden fleshed out Mills. It might be so. A friend of John Muir, Enos Mills might be credited with founding the profession. There had always been people who intuitively did the work. But Mills pointed out the difference between a trail guide — one who safely leads others to a destination; and a nature guide — "a naturalist who can guide others to the secrets of nature" (page 6). Mills established standards and a school for nature guides in the Rocky Mountains. He wrote a number of books, but this is the place to start. Adventures of a Nature Guide provides a wonderful blend of experience and philosophy Also see Alan Leftridge, "A Conversation with Enda Mills Kiley," Legacy, 12 (November/December 2001): 10-17, 46.

Interpreting for Park Visitors, William Lewis, Acorn Press, 1989.

Lewis had a huge influence on interpretation. One of the first to articulate the use of and importance of interpretive themes, he focuses on technique. Lewis provides a practical approach for delivering all sorts of interpretive products and services to all sorts of audiences. New and experienced interpreters alike will benefit by applying his suggestions, especially if they approach Chapter 8, "Self Evaluation" with honesty and integrity.

The Edge of the Sea, Rachel Carson, Houghton Mifflin, 1955.

Carson's Silent Spring, published in 1962, is often credited with inspiring the modern environmental movement. Her earlier works, however, were quite popular and had significant interpretive content. In this piece Carson ties the tangibles of the shore to its intangible meanings and helps the reader care more about that ecosystem. Also see Suzanne S. Haley, "Rachel Carson: Interpretive Writer," Legacy, 11 (March/April 2000): 31-33.

Environmental Interpretation: A Practical Guide for People with Big Ideas and Small Budgets, Sam H. Ham, North American Press, 1992.

Probably the most used textbook on interpretation, its author Sam Ham has been described as the profession's most popular spokesperson. This text begins with solid and understandable interpretive philosophy and communication fundamentals. Ham then connects them to practical and realistic techniques and strategies for creating a variety of interpretive products and services, including school programs and exhibits. (See Eric Fronk, "A Conversation with Sam Ham," Legacy, 9 (September/October 1998) 17-18, 28-37.

Interpretation for the 21st Century: Fifteen Guiding Principles for Interpreting Nature and Culture, Larry Beck and Ted Cable, Sagamore Publishing, 1998.

This text deftly embraces the best practices and philosophies of the past and applies them to contemporary challenges. Beck and Cable recognize and address how evolving technology, changing populations, the value of social science, and the need for partnerships and community support effect the profession. An important work.

Personal Interpretation: Connecting Your Audience to Heritage Resources, Lisa Brochu and Tim Merriman, The National Association for Interpretation, Singapore, 2002.

Lisa Brochu, Program Director, and Tim Merriman, Executive Director of The National Association for Interpretation present the most current ideas in the interpretive profession while incorporating much of the wisdom of the past. A terrific primer for anyone who wants to be a front line interpreter.

Filling the Gap

Dave Dahlen, National Park Service

Part 2

So What?

In support of the organization's mission and mandates, an interpreter must develop a professional approach to seeking out relevant elements of the stories, issues, controversies, multiple perspectives, and management challenges that convey these important topics to the public.

Knowing the facts, relationships, histories, and other informational elements of your site is the first step. In order to present those stories in relevant ways to the visiting public, the interpretive professional then builds from that foundation, broadens it with additional insights, contrasting opinions, additional perspectives, and other information. The audiences we serve as professionals are then in a position from which they can choose whether the relevance and meanings they associate with the place are powerful enough for them to become stewards of that place.

On that beautiful day when I passed through that human-engineered gorge the irony demanded consideration. Contrasting the natural, water-carved gap in the Appalachians with a man-made slice out of an otherwise intact ridge line is a stark comparison.

Why did people choose to preserve one and change the other? What was the depth of discussion, in both instances, that allowed such disparate outcomes to be reached? Did those smiling, happy supporters at the dedication of the water-gap reserve realize that the universal concepts dancing through the air in song and speech unite us in powerful ways?

Did they recognize that the ultimate message sent by preserving the water-gap not only serves us in the near term, but reaches farther into the future than any of them will experience? Did those smiling, happy supporters who cut the ribbon at the excavated gap understand those same principles, except in a different way?

Professionals in interpretation must understand the complexities of these and countless other comparisons and choices facing this and all societies. There are no easy answers or short-term solutions. Each and every interpreter must invest in this process, because they only have brief careers in the larger scheme of things.

Setting the standards of interpretation to an equitable level with that of other professions is the first step. There are no more final answers to what interpretation is and what it is capable of. Only greater understanding of its depth and potential, and of our opportunity to develop ourselves. There is much to learn, and there is much to share.

Helping inform the public so it recognizes the complexity and implications of issues facing resources is all we can hope to accomplish in our lifetimes. Environmental and cultural choices will never cease to be complex, and battles will be won and lost. If we succeed, however, in developing ourselves to our fullest potential, we will enable those interpreters who come after to take what we've done to the next level, just as we added our voices to those who prepared the ground before us. They will continue to elevate the dialogue about who we are as a species, where we're headed, and why it matters.

| EXERCISE |

Write a personal contract with the profession. Your contract should be brief and include a commitment to your subject matter and resource, your audience, the perfection of your interpretive skills, and the personal desired outcomes of your interpretive work. Your contract should not be a definition of interpretation, but a statement of what you stand for and want to accomplish through interpretation. |

Excerpts from Personal Contracts for Interpretation

"I believe the tangible and intangible resources of the places we protect can touch every individual intellectually, emotionally, and spiritually. It is my duty as an interpreter to facilitate the experience by finding the right arrow.

"I will make the program enjoyable to the audience, giving them a souvenir to take home in their mind and heart."

"I will not shy away from subjects that may cause uneasiness or discomfort but will try to present those subjects in a balanced and sensitive manner. I will also try to present multiple perspectives, remaining mindful that the life experience of all visitors is not the same. I must always try to become a conduit as well as a catalyst, supplying accurate information while encouraging a sense of wonder and a hunger for something more."

"I am a tool through which others are able to craft an experience. I must maintain a cutting edge for the hands of the craftsmen, that they may shape their own beliefs, thoughts, views, and conclusions. All of this so that one day others may encounter these wonders in awe."

"Throughout my life I've had the good fortune to feel the awesome majesty, power, beauty, and splendor of this country's natural, historical, and cultural wonders. Because of this, my life is better. I would share that with others."

"As the ocean waves continually lap upon the shore, I will be as dependable as they to both visitors and employees. My reputation will include reliability and dependability."

|

"NEVER DOUBT THAT A SMALL GROUP OF THOUGHTFUL, COMMITTED PEOPLE CAN CHANGE THE WORLD. INDEED, IT'S THE ONLY THING THAT EVER HAS." —Margaret Mead

|

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

meaningful_interpretation/mi6l.htm

Last Updated: 29-May-2008

Meaningful Interpretation

©2003, Eastern National

All rights reserved by Eastern National. Material from this electronic edition published by Eastern National may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of Eastern National.