|

John Day Fossil Beds

Rocks & Hard Places: Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter One:

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AND CULTURES

For more than 10,000 years, humans have inhabited the land now known as Oregon. Anthropologists today consider north-central Oregon a part of the traditional culture area of the Columbia Plateau Indians. Within this region, native peoples spoke languages classified as Sahaptin. Sahaptin-speaking aboriginal groups included the Tenino, Umatilla, Molalo, Cayuse, and Nez Perce (Toepel 1979: 29-47). By the nineteenth century, however, native Plateau peoples shared portions of the upper John Day watershed with Northern Paiute Indians, in a sometimes tense and unfriendly association. The Northern Paiute were speakers of Shoshonean languages, and came from the Great Basin culture area to the south.

"Western Columbia River Sahaptins" are more commonly identified as the Tenino or Warm Springs, the Wyampam, and the John Day. The Columbia River, passing through the northern portion of their homeland, was an integrating force, not a boundary. Sahaptin distribution extended along both the Oregon and Washington shores of the Columbia from the vicinity of Alder Creek, Washington, and Willow Creek, Oregon, west to The Dalles. They occupied the watershed of the Deschutes downstream from its confluence with the Crooked and Metolius rivers, and they held most of the watershed of the John Day River. (Hunn and French 1998: 378-380).

The earliest episodes of contact with Euro-Americans confirm a pre contact dynamic which, for a time, altered the tribal distribution in the watersheds of the John Day and Deschutes rivers. Horses were the probable decisive factor. The acquisition of horses in the eighteenth century by the Northern Paiute, Bannock, Shoshone, gave them a remarkable mobility and advantage over the Sahaptins to the north who did not have horses or who, at best, had small herds. In 1805, the Lewis and Clark Expedition found most villages along the Oregon shore of the Columbia River west of the Snake confluence abandoned. The raids of warriors on horseback from the Great Basin had literally driven the Sahaptins onto the islands or to the more defensible villages on the north shore of the Columbia.

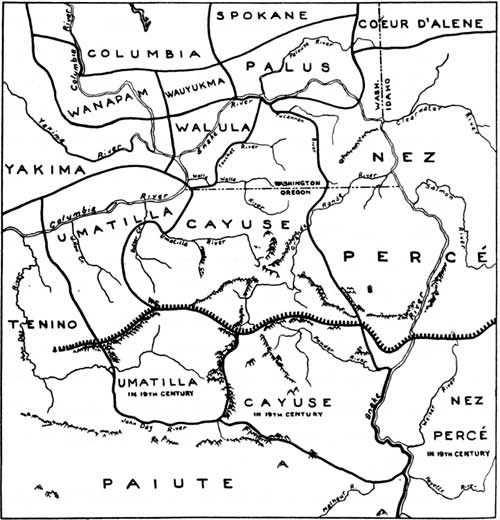

Fig. 2. Hypothetical tribal distribution in

northeastern Oregon and adjacent regions, eighteenth and nineteenth

centuries. Serrated line represents probable northern boundary of

Northern Paiute in the eighteenth century and earlier (Ray et al. 1938:

386).

A revealing place name, "River Towarnahiooks," the "river of the enemies" which Lewis and Clark noted for the Deschutes, spoke to the tension and dislocation which had occurred in that era. William Clark wrote:

The probable reason of the Indians residing on the Stard. [i.e. north bank] of this as well as the waters of Lewis's [Snake] River is their fear of the Snake Indians who reside, as they nativs Say on a great river to the south, and are at war with those tribes . . . (Moulton 1983 — [5]: 318, 321-323, 326).

The John Day Band

The various units of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument were all part of Sahaptin country in the nineteenth century. While some Indians lived in the region throughout the year, many moved in an annual "seasonal round" shaped by the availability of resources and their skills in extracting a living from the land. In their annual round, the John Day band engaged in three primary activities: fishing, gathering, and hunting.

The culture of the John Day band in the contact period responded directly to the environment of the Columbia River, its tributaries, the surrounding sagebrush-steppe plain, and the more distant mountains. The region was an arid landscape in the midst of one of the continent's largest rivers. Abundant fish, large mammals, and bountiful root crops — more than twenty-five species — as well as berries and other plant products provided diversity and nutritional balance in their subsistence. The harvest of nature's commodities was carried out within the rich, ceremonial life of these people. "First fruits" ceremonies, root festivals, and "first salmon" rituals date from pre-contact times and persist to the present. Among these are the spring Root Feast in April and the Huckleberry Feast in early fall (Hilty et al. 1972: 3).

Important plant resources for the Tenino (Warm Springs), and undoubtedly for the John Day band, included the following:

- Blue Camas (Camassia quamash), "Wakamo."

- Bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva), "Pe ah ke."

- Wild Celery (Lomatium nudicaule), 'Cum-see."

- Biscuit Root or Bread Root (Lomatium cous), "Coush" or 'Cous."

- Canby's Desert Parsley (Lomatium canbyi), "Luksh."

- Indian Carrot or False Caraway (Perideridia gairdneri), "Saw-wictk."

- Field Mint (Menthia arvensis), "Shu-ka, Shuka."

- Blue Huckleberries ( Vaccinium), "We woo no Wash."

- Chokecherries (Prunus demissa), "T-mish."

- Black Lichen (Alectora), "Koonts" (Hilty et al. 1972).

The root and berry harvests occurred between April and October. The mid-summer months drew families to the mountains to harvest the succession of ripening berries as well as acorns, hazel nuts, pine nuts, seeds, and "black moss," the tree lichen. The plant resources included also the flower stalks of balsam roots — eaten raw — and the stems of Cow Parsnip (Hunn and French 1998: 381-382).

The rivers were filled with life. Salmon, sturgeon, steelhead, trout, lamprey, suckers, and freshwater mussels insured food surpluses. The people harvested these at falls, narrows, and eddies. They held the greatest fishery in the Pacific Northwest, fabled Celilo Falls, where the Columbia surged over ledges of basalt before entering miles of narrows. Here the stream literally turned on its side before entering the main cleft of the Gorge. The men positioned wood platforms on pole footings over the roily water and with dipnets harvested immense quantities of fish. These were filleted, skewered with cedar sticks, and wind-dried in fish-processing sheds lining the banks of the Columbia. They also fished with seine nets and, in smaller streams, employed weirs, hook-and-line, gaffs, and fish clubs. The fishery was so productive that it made the Tenino and their neighbors wealthy. Preservation of their catch was extremely important, for between October and April — a period of over five months — there were no salmon runs in the rivers. Weeks of intense work to catch and preserve fish were critical to cope with lean times and getting through the long and often bitterly cold winters of the Plateau (Hunn 1990: 90, 119-130).

John Day band men were avid hunters. They pursued mule deer, elk, bighorn sheep, white-tailed deer, bear and pronghorn. They also hunted western gray squirrels, ground squirrels, coyote, gray fox, red fox, mountain lion, bobcat, lynx, otter, long-tailed weasel, raccoon, porcupine, yellow-bellied marmots jackrabbits, cottontail rabbits, ducks, geese, grouse, and swans. The hunting techniques were varied: bow and arrow, net traps (for birds), and snares. These animals provided not only food but hides for clothing, decorative materials robes, sinew for lashings and bowstrings, and cases for quivers (Hunn and French 1998: 382-383).

The shelters of the Indians of the western Plateau were varied. They constructed conical or A-frame, pole and mat-covered lodges. These included both individual units such as for a family as well as communal lodges, joined together with a series of hearths and activity areas along a single axis. Banked earth around the lower outside walls and an excavated floor two to three feet below the ground provided insulation from both the summer sun and winter winds and snow. In the summer they constructed circular, mat-covered tepees or open-walled brush surrounds. Their sweat lodges were low, dome-shaped structures constructed with willow branches and covered with wild rye grass and earth, the floor scented with fir boughs. They also built low huts, often covered with mats but sometimes with cedar planks, as drying sheds for curing fish (Hunn and French 1998: 384-385).

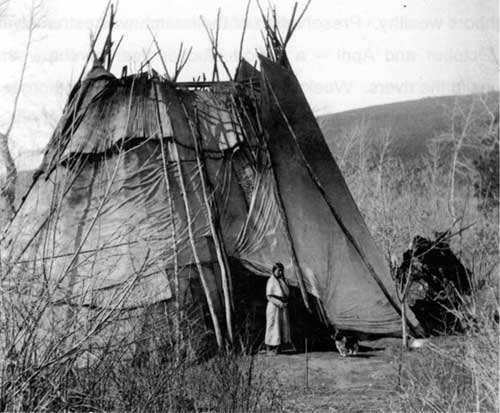

Fig. 3. Warm Springs Indian woman and

traditional lodge of vertical poles with cattail matting, hides (and

later canvas) (OrHi Lot 467-29).

On islands and promontories overlooking the river they erected burial houses. On October 20, 1805, while near the mouth of the John Day River, William Clark described one of these buildings:

[T]he Vau[l]t was made by broad poads [NB: boards] and pieces of Canoes leaning on a ridge pole which was Suported by 2 forks Set in the ground Six feet in hight in an easterly and westerly direction and about 60 feet in length, and 12 feet wide, in it I observed great numbers of humane bones of every description perticularly a pile near the Center of the vault, on the East End 21 Scul bomes forming a circle on Mats — ; in the Westerly part of the Vault appeared to be appropriated for those of more resent death, as many of the bodies of the deceased raped up in leather robes lay [NB: in rows] on board covered with mat, &c. . . .

Deposited with the bodies were wood bowls, baskets, skins, fishing nets and trinkets as well as horse skeletons (Moulton 1983-[5]: 311-312).

The women tanned hides and manufactured leather dresses, leggings, shirts, breechclouts and moccasins for clothing. Rabbit skins, dried with the fur, became mittens and stockings. Rabbit skins, cut into strips and twisted, were made into warm blankets. The women usually wore a basket hat woven of Indian hemp or, by the end of the nineteenth century, a cap made of corn husks (Hunn 1990: 141, 143). Contact with Euro-Americans and the Sahaptin speakers' hold on trade at Celilo Falls, provided a steady flow of new commodities by the end of the eighteenth century. Entering Sahaptin-speaking country on October 20, 1805, William Clark described the natives:

The men are badly dressed, Some have scarlet & blue cloth robes. one has a Salors jacket, The women have a Short indiferent Shirt, a Short robe of Deer or Goat Skins, & a Small Skin which they fastend. tite around their bodies & fastend. Between the legs . . . (Moulton 1983 — [5]: 309- 311).

Basketry was one of the most expressive and elaborately developed art forms of the Tenino. Utilitarian cedar bark baskets, devices manufactured from a piece of bark bent and stitched, might serve for berry-picking or hauling materials. Beautifully decorated work, however, dominated. The women collected hazel basket, bear grass, Indian hemp and other materials. They manufactured a large inventory of baskets: twined hats, twined root-digging bags, flat twined bags, coiled cedar baskets, and round twined bags. They also manufactured hide parfleches or flat cases for carrying dried food and household goods, especially on horseback (Schlick 1994).

Men made whistles out of bones, steamed and bent bighorn sheep horns for spoons and bowls, and hunted eagles and flickers for decorative and sacred feathers. They wove nets from Indian hemp, carved juniper logs for hide-covered drum frames, manufactured stone pestles, ax heads, adzes, and net sinkers. They used canoes, but probably obtained most of these by trade with people living to the west who had easy access to cedar trees for construction of dugouts (Hunn and French 1998: 382-383).

The Indians of the western Plateau were arbiters of commerce. From central Oregon they obtained prized obsidian. In the mountains they picked and preserved berries, gathered bear grass, and tanned hides and furs. Along the rivers they caught and preserved vast stores of dried fish. They captured or bartered for war captives and kidnap victims. They traded these "wealth items" at the falls of the Columbia — the center of a regional economy. The commodities passed down the river in exchange for dried smelt, olivella shells, dentalium shells, wappato roots, dugout canoes and paddles, and, after Euro-American contact, cotton and wool clothing, firearms, metal tools, glass beads, brass kettles, metal fishhooks, and other items of utility and decorative value (Stern 1993: 22-23).

They founded their social organization on both maternal and paternal kinship connections. Over time this created a web of relationships, bonding siblings, generations, and communities. Hunn and French (1998) have identified four levels of connection: nuclear family, hearth group, winter lodge household, and the village. Polygynous marriage created yet another set of connections. Village headmen achieved their positions through ability, eloquence, generosity, and devotion to others. The position passed from father to son, provided the son possessed the virtues necessary to have standing among his relatives and others. Celilo village had a "salmon chief' by the early twentieth century. His role was to open and close the season or stop the fishery for escapement or ceremonial reasons. Some villages had a "whipper," an elder who was to mete out punishments with willow withes to unruly children (Hunn and French 1998: 386-387).

Spirit quests at puberty for boys and days of sequestering in the menstrual hut for girls marked rites of passage. These were not noteworthy times of public rituals but activities for all as they passed from childhood into adulthood. Shamans facilitated communication with the spirit world and, through repeated vision quests, gained powers which they displayed publicly when curing the sick or seeking to inflict misfortune on the unwary (Hunn and French 1998: 388-389). Benjamin Alvord, stationed at Fort Dalles, wrote in 1853 about a young Indian male who possessed "elk" spirit power. "The novitiate wished to imitate the elk, who has, from his youth, been the good spirit or guardian of his life. At certain seasons the elk has a habit of wallowing in the mud. The Indian poured several buckets of water into a low place, in the ring in which they were dancing, and after whistling like the elk, laid down to wallow in the mire" (Alvord 1855: 653).

The oral literature of the Wasco and Wishram, Upper Chinookans living west of the Deschutes River, contains numerous cycles of stories involving Coyote, an animating as well as disruptive force in the myth and transition ages. Coyote stories were recounted during the cold months of the long moons in winter as well at the summer berry-picking camps. The oral literature explained how the land came to be and why certain creatures looked as they did and yielded themselves to meet human need (Sapir 1909).

The world of the John Day band was similar to that of the Wasco, Wishram, Wayampam, Tenino and other peoples of the western Plateau. They lived intimately with the land, followed its rhythms with activities attuned to securing a maximum of subsistence resources, and held tenaciously to their pivotal position as key players in the flow of trade and commerce along the river and through the Columbia Gorge. Those people who resided along the John Day River possessed these same lifeways and values. While those who lived away from the main Columbia were less involved in trade and commerce which moved along its waters, they were certainly beneficiaries of its impact.

To the south, however, lived the Northern Paiute and Bannock who sometimes pushed down the Deschutes or into the upper John Day country.

There were thus unsettling times and tensions, especially with the expansion northward of these Indians when they acquired horses in the eighteenth century.

The Northern Paiute

The Northern Paiute, speakers of a Uto-Aztecan language, were also inhabitants of the upper reaches of the John Day River in the early nineteenth century. Anthropological accounts usually confine their residency to the Great Basin, but fur trade diaries document their presence in the John Day region in the 1820s and 1830s and the journals of Lewis and Clark confirm their advance toward the south bank of the Columbia as early as 1805.

Northern Paiutes occupied a vast section of northwestern Nevada and southeastern Oregon. The northern extent of their customary territory included the Crooked River in the Deschutes watershed, streams flowing into Harney and Malheur lakes in the Harney Basin, the Malheur and Owyhee drainages, and a portion of the upper John Day River. They probably held the north slopes of the Aldrich and Strawberry mountains and the bottomlands along the river in the vicinity of Dayville, Mt. Vernon, John Day and Prairie City. Authors of the definitive assessment of these Indians in the Handbook of North American Indians, however, speak of their northern boundary with uncertainty, noting: "On the north, for roughly 300 miles, it continued through an undetermined territory beyond the summits dividing the drainage systems of the Columbia and Snake rivers" (Fowler and Liljeblad 1986: 435-437).

Of the several groups of Northern Paiute, the Hunipuitoka (or, Walpapi), resided in the Crooked River region, while the Wadatoka inhabited the Harney Basin. Either may have made seasonal use of the John Day, especially its fishery. The Northern Paiute of the Columbia and Snake drainages engaged in subsistence activities virtually identical to their northern neighbors. They caught anadromous fish, dug for roots and bulbs, and hunted large game, especially elk and deer. In the Great Basin they depended upon rabbits, marmots, porcupine, ground squirrels, ducks, geese, trout, and lake fish. In that region their gathering activity was extensive and involved use of an estimated 150 species of plants (Fowler and Liljeblad 1986: 438-441).

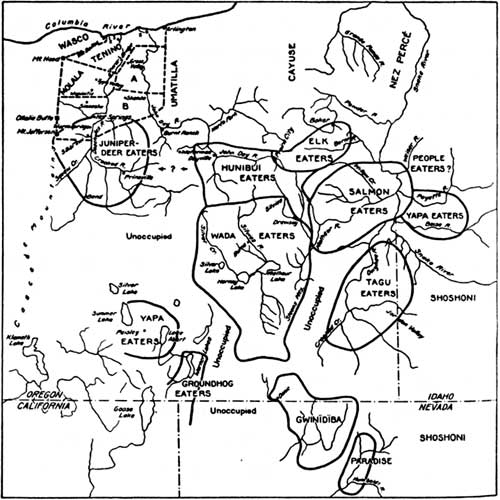

Fig. 4. Hypothetical territory of the

Northern Paiute, denoted by solid lines. Note presence along the John

Day in the vicinity of Dayville and Prairie City (Ray et al. 1938:

396).

The Northern Paiutes resided in rock shelters (when available) and also constructed conical grass or tule-covered winter lodges over frames of willow poles. They covered the frames with bundles of grasses, leaving a smoke hole and providing a skin-covering for the door. In the summer they found little need for shelter, except in more modern times when they erected a four to six-pole, mat-covered or brush-covered shelter for shade (Fowler and Liljeblad 1986: 443).

Their clothing had great variation. In summer women normally wore a single or double apron, knee-length and suspended from a belt. They constructed the aprons from twisted and twined sagebrush bark, rushes, or the skins of ducks and coots. People living more distant from lakes made these aprons from the tanned pelts of coyote, badger, or rabbit. "This costume," wrote Fowler and Liljeblad, "along with appropriate foot-wear and basket cap, is probably the oldest in the region for women and was basic in areas where large game was scarce." In the Oregon portion of Northern Paiute country, however, the women more commonly wore buckskin dresses. Men wore breechclouts in summer and added a buckskin shirt in winter. Both men and women wore moccasins, leggings in winter, and capes when the weather was cold. The women in Oregon normally did not wear caps, but the men did, making them from the pelts of small mammals or from the hides of deer, antelope or sheep (Fowler and Liljeblad 1986: 444-445).

Individual decorations varied but included body tattoos, facial tattoos, ear pendants, eyebrow plucking, and face and body paint, usually reserved for dances as were bone and shell necklaces. Both men and women left their hair loose, but by the 1880s the Plateau influence led both men, and to some extent women, to braid their hair (Fowler and Liljeblad 1986: 446).

The family was at the center of Northern Paiute social organization. It included the nuclear family of parents and children plus widowed grandparents, unmarried parental siblings, and divorced parental siblings. The family was connected through bilateral kinship traced for three ascending and three descending generations. Groups of two or three families, usually related, made up camp groups and often participated together in the seasonal round. Such groups might become larger in winter and smaller in summer, depending on resources and the needs of the community (Fowler and Liljeblad 1986: 447-448).

Because of the necessity for a dispersed and almost constantly moving lifeway in order to survive, the Northern Paiute political organization was the family. Senior family members determined actions. Family groups, sometimes joining in camps, might act in common cause to acquire food or repel aggression. Pipe smoking was a universal act of bonding and was integrally involved in discussions and decision-making. "Headmanship seems not to have been inheritable in this region," noted Fowler and Liljeblad, "with most groups reporting that upon the death of such an individual, another was selected by consensus" (1986: 450-451).

Isabel T. Kelly during the summer of 1930 worked among the Northern Paiute to collect oral literary materials from three bands or larger groups sharing far-flung but customary geographical areas. The texts of tales of the Kuyuitikad ("Sucker-Eaters"), the Gidutikad ("Groundhog-Eaters"), and the Goyatikad ("Freshwater Crab-Eaters"), a band residing in the Summer and Silver lakes region of Oregon, made up Kelly's "Northern Paiute Tales." The literary corpus included tales of creation, origin of fire and the sweat lodge, seasons, accounts of the constellations, and a large repertoire of coyote stories (Kelly 1938).

Cultural Resources Summary

Aboriginal use of the lands around and within John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is today actively affirmed by residents of the Warm Springs, Umatilla, and Burns Paiute reservations. Resident tribes have expressed interest in participating in discussions with the National Park Service regarding the management of cultural resources important to their heritage. This would include any efforts to document and interpret tribal histories in the region (Mark 1996: 237-238). To date, there has been no ethnographic study of lands in or around the Monument; thus, there remains an opportunity to identify any traditional cultural properties, and/or any possible stories or oral traditions associated with the dramatic landforms of the region.

In 1993, the National Park Service contracted for an inventory of archaeological sites within the Monument. This resulted in the re-evaluation of sites already on file at the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office, and a new survey of linear transects in all units of the park. Twenty-five new prehistoric and historic sites and six isolated artifact localities were located, bringing to thirty-six the total of archaeological sites recorded in or immediately adjacent to Monument boundaries. The sites located thus far include lithic scatters, stacked rock features or cairns, and a few rock shelters. Since these are considered to represent only a sampling of potential archaeological resources on Monument terrain, the Burtchard report provided direction for further investigation (Burtchard, Cheung, and Gleason 1994:1-10).

By far the most significant prehistoric sites associated with indigenous peoples thus far found within the boundaries of the Monument are the Picture Gorge pictographs. These are a series of six painted panels of rock art located on the sheer rock walls of the canyon at the south end of the Sheep Rock Unit. First reported in the 1930s by Luther Cressman (1937: 32) in his larger study of Oregon petroglyphs, the Picture Gorge pictographs have since been photographed, documented, and analyzed by various scholars and archaeologists.

Cressman noted stylistic similarities with Great Basin pictographs, but postulated that the designs were introduced by Sahaptin-speaking tribes — the influence perhaps coming out of the east from Nez Perce territory or from the Snake River country further south (Cressman 1937: 69). In 1990, a visiting member of the Warm Springs Reservation informed Monument staff that the pictographs had particular spiritual significance to the Wasco Indians. To date there has been no definitive proof of either the origin or age of the rock art at Picture Gorge (Mark 1996: 237, 249). Burtchard, et al., recommended that the pictographs be more comprehensively recorded, and that steps be taken to interpret, protect, and minimize impacts to the most highly visible and accessible rock art. The Burtchard report also notes the Picture Gorge Pictographs as eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places (1994:165-178).

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002