|

John Day Fossil Beds

Rocks & Hard Places: Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Two:

EARLY EXPLORATIONS AND EXPEDITIONS

The upper John Day country was remote, and familiar to the Western Columbia Sahaptins and Northern Paiute alone until well into the nineteenth century. The lands that later would become John Day Fossil Beds National Monument lay distant from the routes of major exploration in the Pacific Northwest. From the 1810s through the 1850s, a parade of explorers came to the region and, while some passed the river's mouth, few ventured up its course. The region remained largely undocumented and unknown to a larger world.

The earliest Euro-Americans to explore the Columbia River east of the Cascade Mountains were Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and the Corps of Discovery. Dispatched by President Thomas Jefferson in 1803, the Lewis and Clark Expedition was charged with finding an easy portage through the mountains of the far west, extending the commerce of the nation, and mapping the unknown lands of North America. In October of 1805, the expedition passed the mouth of the John Day River en route to the Pacific Ocean. The explorers named the stream Lepages River in honor of Jean Baptiste Lepage, a workman in the party (Moulton 1983-[5]: 319). None of the members of the expedition ascended the river.

John Day — Origin of the Place Name

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, both the United States and Britain turned to the interior of the Pacific Northwest in hopes of building and dominating vast fur-trading empires. Two rival enterprises, the North West Company of Montreal and the American-owned Pacific Fur Company, had both entered the region by 1812. From as early as 1789, the North West Company — led by skilled explorers Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser, and David Thompson — gradually expanded its fur-trading network westward through what is now British Columbia. In 1810, John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company dispatched an overland party led by Wilson Price Hunt to establish a base of operations at the mouth of the Columbia River.

One member of Astor's overland expedition was John Day (1771-1819/20), a backwoods Virginian and experienced hunter, trader, and miner. Day was said to have been tall, handsome, and physically robust, but was no longer youthful when he joined the expedition. On the banks of the Snake River in Idaho, Day fell ill, and was left behind with his associate Ramsay Crooks. The following spring, the two men reached the mouth of the river, which subsequently bore his name. Near this stream, the men were robbed by Indians and stripped of their clothing. Day and Crooks were soon rescued by the Robert Stuart party of Astorians, and taken on to the newly established post at Astoria, arriving in May of 1912. Day later reportedly suffered either a mental breakdown or disability from extreme depression, but remained in the region in the fur trade even after the sale of the Pacific Fur Company in 1813. He died in 1819/20 in the Snake River watershed (Elliott 1916: 373-374; McArthur 1974: 392-393).

With scant historic documentation to explain it, trapper John Day became legend in the region. His name was forever imprinted on the land through the John Day River and its basin, the community of John Day, and John Day Dam on the Columbia.

Fur Trade Explorations

In 1821 the Hudson's Bay Company succeeded to the interests of the North West Company in the Pacific Northwest. George Simpson, governor of its operations in North America, visited the Columbia watershed in 1824 and laid plans to strengthen British control of the fur trade. Simpson moved the regional headquarters from Astoria to a new post, Fort Vancouver, situated on the north bank of the Columbia near its confluence with the Willamette River. He was also made aware of the steady westward advance of Americans and the real prospect they would soon press beyond the Rocky Mountains. Sensing the potential of the Snake River watershed, he wrote:

If properly managed no question exists that it would yield handsome profits as we have convincing proof that the Country is a rich preserve of Beaver and which for political reasons we should endeavor to destroy as fast as possible (Rich and Johnson 1950: xlii).

Simpson's strategy was to dispatch a succession of brigades into the watershed of the Snake River and to trap out its fur-bearing animals. His plan would bring economic returns to the company in the shorter term and create a region so devoid of small mammals that the Americans, once they crossed the mountains and entered the region, would turn back in frustration. Peter Skene Ogden drew the primary assignment to execute the policy. Ogden's travels in connection with this assignment made him the first Euro-American to enter and explore the John Day basin.

Ogden's first expedition into the Snake country occurred between December, 1824, and October, 1825. At Fort Nez Perces on the Columbia River at the mouth of the Walla Walla, Ogden outfitted a return brigade. Throughout the fur trade era, Fort Nez Perces (subsequently known as Fort Walla Walla) was a center of influence among Sahaptin-speakers and Northern Paiute of the Columbia Plateau. Alexander Ross and Donald Mckenzie of the North West Company had built the post in 1818 at the junction of the Walla Walla and Columbia rivers just east of Wallula Gap. Constructed originally of timber, the post burned in 1841 but was reconstructed of adobe and continued in use into the era of overland emigration. During the fur trade, the post was singularly significant as an administrative center for the great "horse farm" operated by the Hudson's Bay Company. Horses for the brigades were supplied from the herds at Fort Nez Perces. It also was an important depot for trade goods flowing into the lives of Native Americans who resided in the region (Stern 1993, 1996).

Fig. 5. Fort Nez Perces (Walla Walla) at

the confluence of the Walla Walla and Columbia rivers, 1855. (OrHi

1651).

Peter Skene Ogden departed Fort Nez Perces on November 21, 1825, proceeding west across the Columbia Plateau to The Dalles. He and his brigade then ascended Fifteen Mile Creek, crossed to the Deschutes watershed, ascended the Crooked River, and then dropped into the watershed of the South Fork of the John day where the party camped on January 11, 1826, Ogden wrote:

... the country we came over this day well wooded with Norway Pine & also a tree strongly resembling the Box wood and altho I may be mistaken it greatly resembles it — the Soil good but stoney we had for part of the day about three inches of Snow distance this day 15 miles 3 Beavers (Rich and Johnson 1950: 113).

Ogden's party had success, taking 265 beaver and nine otter in the Deschutes watershed, but found icy conditions and near starvation on the John Day. On January 14, south of present Dayville, Ogden wrote:

We started early our course W and by N. for three miles and then North 6 miles along the main Branch of Deys River a fine large Stream — nearly as wide again as it is at the entrance of the Columbia and from appearance this river as well as the River of the Falls [Deschutes] also Utalla [Umatilla] take their sources from nearly the same quarter consequently the two first are very long from the winding course they take and from appearances Deys River must have been well stocked in Beaver — but all along our route this day we found Snake Huts [i.e., Northern Paiute lodges] not long since abandoned and from appearances have been killing Beaver from their want of Traps they destroy not many but the remainder become so shy that it is very difficult to take them . . . (Rich and Johnson 1950: 114).

Ogden's brigade entered the main valley of the John Day on January 17. He and his men remained for several days, catching both beaver and otter but coping with high water and loss of their traps. They discovered the beaver were shy or spooked because the Indians had raided the beaver dams and lodges in an attempt to kill the animals to secure pelts for trading at Fort Nez Perces. Ogden found "Snake" (probably Northern Paiute) Indians along the upper John Day. On January 19, for example, he noted:

Early this morning five Snake Indians paid us a visit they traded 6 Large and 2 small Beavers for Knives & Beads and 10 Beavers they traded with my Guide for a Horse I treated them kindly and made a trifling present to an Old man who accompanied them and as far as I could Judge from appearances they appear'd to respect, they were fine tall Men and well Dress'd, and for so barren a Country in good condition (Rich and Johnson 1950: 117).

The privations this party endured were many: hunger, ice, and uncertainty about its route. At the base of the Blue Mountains, where Ogden was about to commence a difficult crossing to Burnt River, he reflected: "we shall leave the waters of Dey's River and I have to remark altho we have taken some Beaver a poorer Country does not exist in any part of the World . . . (Rich and Johnson 1950: 119).

Ogden's men had trapped 185 beaver and sixteen otter along the John Day. His 1825-26 brigade took him as far east as Fort Hall. He then turned westward, working down the south bank of the Snake, exploring the Bruneau River, and finally ascending Burnt River to retrace his party's January trip through the upper John Day River region. He reached the John Day again on July 1 but did not tarry. On July 3 the expedition ascended the hills to the west to the Crooked River. Ogden guided his party on to the Deschutes, crossed the Cascade Range, and then passed through the Willamette Valley to arrive at Fort Vancouver in mid-July (Rich and Johnson 1950: 196-197).

Peter Skene Ogden led Hudson's Bay Company employees through the upper John Day watershed a second time in early July, 1829. This time his brigade moved northward from the Harney Basin up the Silvies River and over the Strawberry Mountains. In the vicinity of Dayville, the trappers found both elk and black-tail deer; the hunters killed six of the latter. Ogden continued on, arriving at what was probably the entrance to Picture Gorge: "Having reached the main stream we proceeded on following it down for six miles, when our progress was again arrested by high and lofty rocks, and as far as the eye can reach it appears to be the same." The party stopped here near the south boundary of what is now the Sheep Rock unit of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument:

We encamped not wishing from the low state of our horses and from the gloomy prospect before us to advance further for this day, but tomorrow I shall make the attempt though I verily believe were it left optional with the trappers prefer to proceed on and pass by the Dalles. This route would lengthen our journey eight days and at this season the natives being most numerous both at the Falls and Dalles stand a chance of having our horses stolen. Thus situated I am determined to persevere by this river . . . (Williams et al. 1971:164).

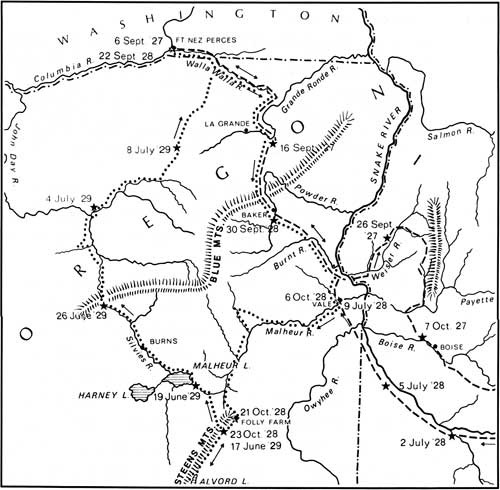

Fig. 6. Ogden's campsites in the John

Day watershed, June — July, 1829. Legend of expedition routes

1828-29; 1827-28 (Williams, Miller and Miller 1971: map).

Continuing downriver the next day, apparently having bypassed Picture Gorge, Ogden's party found a Northern Paiute camp "of fifty men with their families all busily employed with their salmon fisheries." In short order he bartered for fish and obtained two hundred salmon. Ogden wrestled with the vagaries of the men in the brigade:

Canadians are certainly strange beings — in the morning more curses were bestowed on me than a parson would bestow blessings in a month, and now they find themselves rich in food with a fair prospect of soon reaching the end of their journey I am in the opinion of all a clever fellow for coming this way. Such is the nature of the men I have to travel with in this barren country, and truly may it be remarked the reverse of being an enviable one, and if any man be of a different opinion let him make the experiment and he will soon be convinced (Williams et al. 1971: 164-165).

On July 4 Ogden's party reached the North Fork of the John Day at the present town of Kimberly, and was fortified by the purchase the previous day of twenty fresh salmon. He led his party up the North Fork for three days, then turned northward toward Fort Nez Perces, which they reached on July 9. "This ends my fifth trip to the Snake Country," he observed, "and so far as regards my party have no cause to complain of our success" (Williams et al. 1971: 165-166).

The journals of Peter Skene Ogden's two brigades of the 1820s, both of which entered the John Day watershed, confirm active use of the region by fur seekers and the presence of Northern Paiute Indians along the upper river. Although the Northern Paiute were culturally a Great Basin people, they were clearly engaged in the salmon fishery during Ogden's visit in the summer of 1829. Ogden also noted the presence of the Cayuse in the upper John Day region, observing what he described as the "remains of a Cayouse camp of last fall" and what he thought was the "Cayouse camp road" (Williams et al. 1971: 163-164).

Another Hudson's Bay Company brigade leader working in the Snake River watershed explored the John Day basin. John Work led his party north from Harney Basin via the Silvies River into the John Day valley in July of 1831. Work wrote: "Crossed the mountains to Day's River, a distance of 22 miles N. W. the road very hilly and steep, particularly the N. side of the mountain. The mountain is thickly wooded with tall pine timber." Work's men camped on the John Day River and bartered for five beaver pelts from two Indians. The next day the trappers traveled sixteen miles down the river to the vicinity of present Dayville. On July 12 Work wrote about his travels and an Indian fish weir:

. . . we stopped near a camp of Snake Indians who have the river barred for the purpose of catching salmon. We, with difficulty, obtained a few salmon from them, perhaps enough to give all hands a meal. They are taking very few salmon, and are complaining of being hungry themselves. No roots can be obtained from them, but some of the men traded two or three dogs, but even the few of these animals they have are very lean, a sure sign of a scarcity of food among Indians. We found two horses with these people who were stolen from the men I left on Snake River in September last. They gave up the horses without hesitation, and said they had received them from another band that are in the mountains with some more horses which were stolen at the same time . . . Part of the way today the road lay over rugged rocks on the banks of the river, and was very hard on the already wounded feet of the horses. Five beaver were taken in the morning (Elliott 1913: 311-312).

Work's men remained in camp on July 13 — weary and hungry, obtaining only three salmon from the famished Indians. "They complain of starving themselves," he noted. On July 14 the Hudson's Bay Company brigade traveled twenty-five miles down the John Day River and on July 15 continued another eight miles to the North Fork at Kimberly and ascended it for seven miles. "The road hilly and stony," he wrote. "These two days the people found great quantities of currants along the banks of the river." On July 16 the brigade continued another eight miles up the North Fork then cut across the mountains toward Fort Nez Perces (Elliott 1913: 312-313).

Work's brigade reached Fort Nez Perces on July 18. Two days later he described his ambitious expedition:

Since our spring journey commenced we have traveled upwards of 1000 miles, and from the height of the water and scarcity of beaver we have very little for the labour and trouble which we experienced. Previous to taking up our winter quarters last fall we traveled upwards of 980 miles, which, with the different moves made during the winter makes better than 2000 miles traveled during our voyage.

Work's brigade lost eighty-two horses by drowning, theft, death, or being killed for food (Elliott 1913: 314).

During the fur trade era, several scientists also entered the region and passed by the mouth of the John Day River. These included the botanist David Douglas and naturalist John Kirk Townsend. Douglas, a Scottish explorer in the employ of the Royal Horticultural Society of London, traveled up and down the Columbia on plant-collecting expeditions. He sought new ornamentals to introduce into European gardens. Townsend traveled overland in 1834 with Thomas Nuttall, a botanist from Harvard University. Both collected specimens and made notes on their observations. Townsend sold his duplicate bird and animal skins to John James Audubon who used them in his books on birds and mammals (McKelvey 1991: 299-341, 586-616).

Nathaniel Wyeth, an American fur trapper and company owner, explored the Deschutes watershed to the west of the John Day in 1835. An ice merchant who had prospered in Massachusetts, Wyeth sought to compete with the Hudson's Bay Company. He traveled overland to Oregon in 1832 to examine prospects, returned east in 1833, and formed the Columbia River Fishing and Trading Company. He dispatched supplies and personnel on the May Dacre, a vessel he planned to use for the export of salted salmon to Hawaii, and in 1834 returned to Oregon. His overland party of twenty included the naturalists Nuttall and Townsend as well as the Methodist missionary Jason Lee and his compatriots (Sampson 1 968[5]: 381-401).

Wyeth founded Fort William on Sauvies Island at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia rivers and established a farm on French Prairie to grow vegetables and produce livestock for his employees. He personally concentrated on trapping south of the Columbia River in the watershed of the Deschutes River. Winter conditions, hunger, lack of knowledge of the terrain and survival techniques beleaguered the Wyeth party. Far up the Deschutes in January, 1835, camping amid snowdrifts three feet deep, he penned a lamentation in his journal:

The thoughts that have run through my brain while I have been lying here in the snow would fill a volume and of such matter as was never put into one, my infancy, my youth, and its friends and faults, my manhoods troubled stream, its vagaries, its aloes mixed with the gall of bitterness and its results viz under a blankett hundreds perhaps thousands of miles from a friend, the Blast howling about, and smothered in snow, poor, in debt, doing nothing to get out of it, despised for a visionary, nearly naked, but there is one good thing plenty to eat health and heart (Young 1899: 241-243).

Wyeth, a man of many interests, recorded the first geological comments on Oregon east of the Cascades. On February 6, 1836, on the Deschutes, he noted:

. . . the upper part of the mountain was of mica slate very much twisted this afternoon the rock was volcanic and in some places underlaid with green clay Saw today small bolders of a blackrock which from its fracture I took to be bituminous coal but its weight was about that of hornblende perhaps it might be Obsidian but I think was heavier than any I have ever seen (Young 1899: 249).

A fortune in furs and salmon slipped from Wyeth's grasp. The realities of the Oregon country and the stiff competition of the Hudson's Bay Company proved too much. He withdrew and returned in 1836 to Boston to resume his career as an inventor and ice merchant (Sampson 1968: 397-401).

Further Government Exploration

In 1841 a contingent of the U. S. Exploring Expedition ascended the Columbia River as far as Fort Walla Walla (formerly Fort Nez Perces) and the Whitman Mission to make a reconnaissance and map the western portion of the Plateau along the margins of the river. The detachment, led by Joseph Drayton, traveled with a Hudson's Bay Company brigade led by Peter Skene Ogden. Nine boats and sixty men in the employ of the company set out in June to ascend the river. The party reached the mouth of the John Day in early July. Charles Wilkes, commander and author of the five volume overview of expedition labors, noted:

At John Day's river great quantities of salmon are taken, and there are, in consequence, many temporary lodges here. Notwithstanding this is a rocky region, there are vast quantities of fine sand deposited every where, which is brought down the river. On this the encampments are necessarily made; and the sand is exceedingly dry and hot, which renders the camping disagreeable. There are few places more uncomfortable; for a basaltic wall rises nine hundred feet or a thousand feet within two hundred yards of camp, which reflects the sun's rays down upon the beach of white sand, rendering the atmosphere almost insupportable (Wilkes 1845[4]: 381-389).

The explorers went on a rattlesnake hunt, killing several, and then moved on into the more arid stretches of the Columbia between the John Day and Walla Walla rivers (Wilkes 1845[4]: 381-389).

In the fall of 1843, John C. Fremont and his exploring party, following the large contingent of overland emigrants, traveled the Oregon Trail and mapped its route to Fort Walla Walla. Fremont's travels took him across the Columbia Plateau to The Dalles. He left most of his men encamped there while he made a hurried trip through the Gorge to Fort Vancouver. Upon his return, his party turned south along the eastern flank of the Cascade Range and entered the Great Basin. Like other explorers, his only contact with the John Day watershed was to cross the river near its mouth. The significance of Fremont's exploration lay in the superb maps of the Oregon Trail prepared by Charles Preuss, the flowing and romantic revision of his diaries edited by his wife, Jessie (Benton) Fremont and published by the Government Printing Office in 1845, and his recognition that a vast section of the inter-montane American West had no connection to the sea. He perceived the existence of the Great Basin and articulated the concept in his writings (Fremont 1970).

On the eve of Euro-American penetration of the John Day country, the U.S. Army mounted two military explorations into southeastern Oregon. The first was a reconnaissance of the region under the command of Capt. D. H. Wallen. General William S. Harney, then commander of the Department of Oregon, recognized the need for military routes for moving troops, supplies, and weapons in case of conflict with the Indians and the Mormons in Utah. In April, 1859, Harney ordered Capt. Wallen to examine the drainage of the John Day River to ascertain the feasibility of the construction of a military wagon road between Fort Dalles and the Great Salt Lake. In June, Wallen led 185 enlisted men, nine officers, a physician, and civilian guides and packers eastward. The expedition included 154 horses, 344 mules, 121 oxen, thirty wagons, an ambulance, and bridge pontoons for fording streams. Advance work by Louis Scholl, the guide, confirmed the virtual impossibility of taking wagons via the upper John Day country. Thus in June Wallen's expedition ascended the west bank of the Deschutes before following the Crooked River eastward (Menefee and Tiller 1978: 32-33). Except for the loss of horses to Indians, Wallen's expedition was without incident (Nedry 1952: 237-238).

In the spring of 1860, Harney ordered Major Enoch Steen to continue Wallen's explorations for transportation routes. Harney on January 17 wrote:

It will be perceived . . . that there exists a succession of large and fertile valleys from the Columbia river to the Great Salt Lake, susceptible of maintaining large populations, and which will soon become occupied whenever the facilities offered by good roads are presented . . . To enable the emigrants moving into Oregon to do so more expeditiously, I shall cause a route to be opened from the lake, named as Harney lake upon the map, to the juncture of the road from Eugene city, up the middle fork [of the Willamette] to where it crosses Fremont's road of 1843, south of Diamond Peak (House of Representatives 1859: 208-209).

Capt. A. J. Smith commanded escort troops. This party also avoided the John Day watershed and traveled, instead, up the east side of the Deschutes to the Crooked River and then by way of it to the Harney Basin. The contingent encountered hostilities with the Northern Paiute on June 23, but pressed on as far as Steen's Mountain before turning back to its post (Shaver et al. 1905: 635-636, Menefee and Tiller 1978: 40-41).

Cultural Resources Summary

When the era of the fur trade and early exploration ended in the 1840s, the John Day watershed remained Indian country. Explorers Lewis and Clark, naturalists Douglas, Nuttall, and Townsend, the reconnaissance detachment sent out by Lt. Charles Wilkes, and John C. Fremont all crossed the mouth of the John Day River but did not ascend its course. Hudson's Bay Company brigades led by Peter Skene Ogden in the late 1820s and John Work in the early 1830s are the only parties of Euro-Americans known to have penetrated the John Day basin and passed through the immediate vicinity of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. Their travels, trapping, and trading left no historical traces except for their diaries. Those remained hidden in the company archives at Beaver House in London until published in the mid-twentieth century.

Military expeditions of the 1840s and 1850s provided new, candid information about central and southeastern Oregon. The maps of Henry D. Wallen and Lt. Thomas Dixon filled in heretofore-unknown territory. Published by the Government Printing Office in the Congressional Serial Set, the reports and Dixon map were thus available to anyone who wanted copies. While the upper John Day watershed remained obscure — indicated merely by a dotted line for much of its course — the topographical detail of the surrounding country was now more exactly known.

No cultural resource sites associated with early Euro-American explorations and expeditions have been identified within the boundaries or the vicinity of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. While the general locations of campsites along the John Day River were noted by Ogden and Work in their journals, none can be precisely located or verified on the land.

Ironically, the fleeting presence of the hapless fur trader John Day at the mouth of the stream is commemorated by multiple place names throughout the region. The Corps of Discovery workman for whom Lewis and Clark first named the river, Jean Baptiste Lepage, is remembered at LePage Park, a small local park along Interstate 84 near the mouth of the John Day.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002