|

John Day Fossil Beds

Rocks & Hard Places: Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Four:

SETTLEMENT

The decade of the 1840s unleashed forces that forever changed the Pacific Northwest. Within a seven-year period more than 10,000 emigrants traveled westward over the Oregon Trail. Their presence helped tilt the geopolitical direction of the region.

Euro-Americans brought with them an unquenchable thirst for ownership of land, and a determination to tame the landscape in ways inherently in conflict with indigenous cultures. In a series of halting steps, accompanied by much bloodshed throughout the territory, the U.S. Government moved to extinguish native title to the land. From the 1850s through the late 1860s, the Government pushed various tribes of the region to formalize treaties of cession, even as it enacted sweeping programs of land grants of the public domain.

The discovery of rich gold deposits and vast cattle ranges drew Willamette Valley settlers east across the Cascades in the 1860s. Population in the John Day basin swelled during that decade, but moderated thereafter in the face of a semi-arid climate, scant resource base, and difficult access to markets. Subsistence living on lands around the present-day units of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument remained a formidable challenge to settlers well into the twentieth century.

Oregon Fever

In 1846, under the leadership of President James K. Polk, an avowed expansionist, the United States gave notice to Great Britain that it wanted resolution of the question of national sovereignty in the Pacific Northwest. When negotiations were finished, the United States, through the Oregon Treaty of 1846, secured all of the region lying westward from the crest of the Rocky Mountains and south of the 49th Parallel of north latitude. In the stroke of a pen came closure on the operations of the Hudson's Bay Company and major changes for the region's native peoples.

Why did Americans (and others) contract the "Oregon Fever" in the mid-nineteenth century? The causes were multiple. Favorable publicity was one factor. The journals of the Lewis and Clark expedition, especially the two-volume edition of 1814 edited by Nicholas Biddle, were literally read to pieces by Americans hungry to learn about the Far West. Publication of Astoria (1836) and The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, U.S.A., in the Rocky Mountains and the Far West (1837) by Washington Irving captured the attention of a large public. Samuel Parker's Exploring Tour (1838), John Kirk Townsend's Narrative of a Journey Across the Rocky Mountains to the Columbia River (1839), Ross Cox's Adventures on the Columbia River (1831), and Gabriel Franchere's Narrative of a Voyage to the Northwest Coast of America (1819, first English edition 1854) — all provided specific information about the abundant fish, vast stands of timber, healthy and moderate climate, and agricultural potentials of the region. The scientific reports of the U.S. Exploring Expedition (Wilkes 1845), its subsequent technical reports and illustrated folios, and the journal narrative and maps of the 1843 John C. Fremont expedition, published in 1845, provided authority for the accounts of others.

"Pull" factors included adventure, the prospect of mounting missions to the Indians, and securing free land in the fabled Willamette Valley. Throughout the decade of the 1840s, Lewis Linn and Thomas Hart Benton, senators from Missouri, sponsored bills proposing up to as much as 1,000 acres of free land to those who emigrated to Oregon. Finally in 1850, Congress passed a Donation Land Act. As subsequently amended, it operated until 1855 and enabled 7,437 claimants to secure 2.5 million acres in Oregon (Johansen 1957: viii). Other "pull" factors were the presence of kinfolk in the West, who wrote letters home describing conditions and opportunities in Oregon and the possibility of the discovery of gold (confirmed with the strike in California in 1848 and a succession of placer and lode rushes in succeeding years) (Unruh 1979).

Fig. 8. Residents of upper John Day

valley traveling by buckboard, ca. 1900 (OrHi 23, 213)

"Push" factors included escape from fevers and ill health, a respite from years of repeated flooding in the bottomlands along the Missouri, Ohio, and Mississippi rivers, and a break from creditors in the economic downturn which followed the Panic of 1837. Some felt pushed by the rapid settlement of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri. Many were motivated, however, by the possibility of selling out their improved farms for a profit and gaining free land in Oregon to start over again with a much larger base of potential capital (Unruh 1979: 90-117).

Disposition of the Land

Throughout the period of the land-based fur trade between 1811 and the mid-1840s, amicable relations had generally prevailed between the native inhabitants of the Pacific Northwest, and the Euro-Americans and Pacific Islanders who worked in that enterprise. When conflicts erupted they were resolved efficiently and without spread of tensions (McArthur 1974: 563-564). The era of overland emigration which commenced in 1843 was a different story. The potentials for conflict mounted steadily and were of discernible causes.

The pioneer generation included thousands of rough, uncouth people who, along with their parents and grandparents, had lived on the expanding western frontiers of the United States. Many carried a deep-seated distrust, if not hatred of Indians. This had been nourished by family lore as well as the publication of over 300 "captivity narratives." A lurid, sub-literary genre of autobiographical and biographical accounts by those who had escaped from the clutches of ''savages, " these works created and helped perpetuate a negative image of and attitude toward native peoples (Berkhofer 1988: 534-537; Kestler 1990: xvii-xxxv). Although actual conflicts between Indians and emigrants along the Oregon Trail were few, many distrusted Indians, blamed them for losses of livestock, and considered killing these people an acceptable practice (Farragher 1979: 31-32).

Federal policy failed to respond adequately to the unfolding invasion of Indian lands in the 1840s. Although the United States secured sovereignty in the Pacific Northwest in 1846, Congress took no action to organize a territory and establish courts, military posts, or the activities of the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Instead, congressmen like Lewis Linn and Thomas Hart Benton introduced bills promising grants of large acreages of free land to those who would emigrate to Oregon. When this legislation — the Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850 (9 Stat. 496, amended by 10 Stat. 158 (1853)) — finally passed, the federal government had taken no action to secure cession of any Indian lands by treaty (Buan and Lewis 1991: 39-41).

The U.S. Army had, however, dispatched the Mounted Riflemen overland in 1849. These companies of dragoons established Cantonment Hall in eastern Idaho, occupied old Fort George, the fur trade post at Astoria, and laid out a garrison overlooking the former Hudson's Bay Company headquarters at Fort Vancouver in Washington. Their assignment was to guard the Oregon Trail and protect new settlements (Settle 1940: 265-272).

Other precipitating factors in the eruption of troubles were the parthenogenic consequences of a new population into that of people isolated from powerful, fatal diseases. While smallpox had broken out in the Columbia estuary in the 1790s, it had not killed a significant number. The impact of new diseases, however, unfolded with fury in 1831 and, over the next decade, decimated the Indians of the Columbia estuary and Willamette Valley. Probably as many as eighty percent died and many who remained were ill. Overland emigrants introduced measles and other maladies to the Cayuse, Walla Walla, Umatilla and Nez Perce in the years 1843-47. The Oregon Trail bisected their lands (Boyd 1990: 137-143).

A number of the sick emigrants found succor and restoration of health under the care of Dr. Marcus Whitman. The Indians did not. They died in increasing number (Boyd 1990: 137-143). Some of the Cayuse were convinced that Whitman was an evil doctor or, at best, a failed doctor. In Indian society a healer who failed to cure was liable for malpractice and the penalty was death. On November 29, 1847, a Cayuse party attacked the Whitman Mission. They murdered Marcus and Narcissa Whitman and a dozen others. The survivors fled to the Willamette Valley (Thompson 1969: 92-103).

The incident at Waiilatpu confirmed the worst fears of settlers in the Willamette Valley. Many were convinced that an Indian uprising was underway and that thousands of warriors would fall upon their isolated farms and small villages. The event brought an end to Protestant missionary efforts to the Indians on the Columbia Plateau for nearly twenty years, but it precipitated a new, armed invasion. Within days of receipt of news of the deaths at the Whitman Mission, companies of volunteer soldiers raised by the Oregon Provisional Government set out to teach the Cayuse a lesson. Thus unfolded in 1847-48 the Cayuse War. Hundreds of troops, rag-tailed, untrained, and determined to get back at the "savages" poured through the Columbia Gorge to punish the alleged murderers. Their campaigns proved frustrating; the enemy was elusive (Victor 1894: 194-263). Finally to get them to leave, the Cayuse leaders surrendered five men believed to have been involved in the attack at Waiilatpu. These men were tried and hanged in 1850 in Oregon City (Lansing 1993).

The Cayuse War shocked Congress into action. On August 14, 1848, it passed the Organic Act (9 Stat. 323) to create Oregon Territory. This legislation set the stage, at last, for the unfolding of federal Indian policy throughout the region. It extended the Ordinance of 1787 to all of the Pacific Northwest. The "utmost good faith" clause in that ordinance affirmed aboriginal land title. This meant the federal government would mount a treaty program and reduce Indian lands as provided by the Constitution while, at the same time, defining its relationships with the tribes and identifying their reserved lands, rights, and access to social, medical, and educational programs. Joseph Lane, a resident of Indiana and a military hero from the Mexican War, arrived in the region in March, 1849, to proclaim the creation of Oregon Territory, to assume his responsibilities as governor, and to act, as well, as ex-officio superintendent of Indian Affairs. Lane initiated the first collection of information about the numbers, locations, leaders, and lifeways of the region's native population (ARCIA 1850: 125-135).

The efforts to deal with the Indians faltered. Congress passed a law on June 5,1850, (9 Stat. 437) to create the Willamette Valley Treaty Commission and to extend the Indian Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834 to Oregon Territory. Although the Commission ultimately negotiated six treaties in councils, Congress abrogated its powers and the Senate never considered the agreements. The Trade and Intercourse Act provisions, however, were significant: they prohibited the sale of liquor to Indians, set standards for trade relations, and officially declared that all Indians lands, until ceded by ratified treaty, were "Indian Country." In "Indian Country" tribal law and custom prevailed (Strickland and Wilkinson 1982: 27).

Not until June of 1855, did the respective superintendents of Indian Affairs in Oregon and Washington initiate treaty discussions with the natives of the Columbia Plateau. Driven by the Pacific Railroad Surveys and the prospect of securing a right-of-way for a line from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Puget Sound or the Columbia estuary, Governor Isaac I. Stevens of Washington Territory and Joel Palmer, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in Oregon Territory, assembled several thousand Indians at the great Walla Walla Treaty Council. In a succession of days of presentation, discussion, and persuasion, the negotiators secured treaties with the Nez Perce, Umatilla, Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Yakama. The agreements reserved large tracts of the aboriginal lands to the tribes.

Separately, on June 25, 1855, in a council at The Dalles, Palmer negotiated a treaty with the Warm Springs tribes. The agreement ceded lands throughout much of the Deschutes and John Day drainages but created a reservation of over 600,000 acres. Significantly, all of these treaties reserved hunting, gathering, grazing, and fishing rights for the tribes. Thus, dispossessed of large areas of their lands — including the John Day country — the tribes retained opportunities for basic subsistence activities they had exercised from time immemorial (Beckham 1998: 154-155).

The Indians of the John Day watershed in the latter part of the 1850s were expected by the Bureau of Indian Affairs to locate within the newly designated reservations. To the east, the Umatilla Reservation lay along and into the Blue Mountains in a region bisected by the Umatilla River. To the west was the Warm Springs Reservation which lay along the west bank of the Deschutes. It included the lower Metolius River, the Warm Springs River, and ran west to the summit of the Cascade Range. It is likely that most of the Sahaptin-speaking peoples who had lived in the John Day watershed eventually relocated on the Warm Springs Reservation. There was a greater prospect of kinship and language affinity than with the Cayuse, Walla Walla, and Nez Perce on the Umatilla Reservation (Hunn and French 1998: 389-391; Stern 1998: 414-416).

The treaty situation of the Northern Paiute remained unresolved for another nine years. On October 14, 1864, as cattle grazers were moving into the lush meadowlands of the lakes and rivers east of the Cascades, J. W. Perit Huntington, Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs, negotiated a treaty with the Klamath, Modoc, and the "Yahuskin Band of Snakes." This last group were Northern Paiutes whose homeland included Sycan Marsh and parts of the upper Deschutes watershed. On August 12, 1865, the United States in council at Sprague River in south-central Oregon secured a treaty with the Walpapi band of Northern Paiute under Chief Paulina. It is probable that signatories to this treaty included people who had regularly fished and lived in the upper John Day country. Their treaty ceded lands at Snow Peak in the Blue Mountains, "near the heads of the Grande Ronde River and north fork of John Day's River; then down said north fork of John Day's River to its junction with the south fork; thence due south to Crooked River . . . " and on to Harney Lake and east into the Malheur watershed (Kappler 1904[2]: 876; ARCIA 1866: 5-6).

In this same period the Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs returned to the tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation and on November 15, 1865, secured a second treaty ceding their off-reservation fishing rights. The tribes immediately claimed the treaty was fraudulent and that they had no intention of surrendering these life-sustaining fisheries along the Columbia River. The arguments persisted for the next twenty-three years before the federal government acquiesced and henceforth ignored the 1865 agreement (Beckham 1984a: 110-113).

When the treaties of 1855 were under consideration by the Buchanan administration and the Senate, hostilities erupted on the Columbia Plateau. Generally known as the Yakima War of 1857-58, this conflict was the consequence of the western Plateau tribes sensing the same realities which had impinged upon the Cayuse in 1847: deaths, dislocations, losses of lands, and a mounting tide of Euro-American emigration. The U.S. Army was a central player in the conflicts. It had established Camp Drum, subsequently known as Fort Dalles, in 1850, at the eastern end of the Columbia Gorge on the Oregon Trail (Knuth 1966: 297). In 1855 it erected Fort Cascades at the lowest rapids on the Columbia in the western Gorge and stationed troops in nearby strategic blockhouses — Fort Raines and Fort Lugenbeel at the Middle and Upper Cascades (Beckham 1984b).

The conflicts of 1856-57 occurred in the Columbia River Gorge and in Washington Territory north of the river. As in so much of the early historic period in the Pacific Northwest, the John Day country remained "out back of beyond." It was neither a field of conflict nor of Army, volunteer, or Indian military movement. The Indians of the John Day watershed, as of August 1857, remained in their homeland. A. P. Denison, Agent for Northeast Oregon, wrote:

The John Day Rivers occupy the country in the immediate vicinity of the river bearing that name. Throughout the late war they were with the hostile party; since then they have been friendly and well disposed. They will require but little assistance from the department the present year. The resources of their country are such as to preclude the probability they will require much aid hereafter (ARCIA 1858: 373).

The Bureau of Indian Affairs estimated the population of the Indians of the John Day River as 120 people in 1859. Their leader was known as "House" (ARCIA 1859: 435).

The late 1850s were nonetheless a time of tension for the John Day people in their homeland, as well as for the Wasco, Warm Springs, and other bands who had removed to the Warm Springs Reservation. The Northern Paiute looked jealously at the resources of those tribes. Under the annuities provided by their treaty, the government had purchased clothing, tools, and livestock for them. These assets proved irresistible. The Northern Paiute, as had been their practices for several decades, launched a new series of raids northward. Their goals, in this instance, were plunder and women. The reports of the Indian agents at Warm Springs chronicled the problems which beset the people held there (ARCIA 1859: 801-802). Illustrative were the comments of Agent G. H. Abbott of July, 1860:

When I took charge of this reserve I found the Indians in great fear of their mortal enemies, the Snakes, and during the early spring they were greatly distressed by the depredatory incursions of those unconscionable thieves. It was necessary to herd all stock during the day and corral it at night, and to observe the greatest vigilance at all times (ARCIA 1860: 442).

In time, the Northern Paiute incursions abated. A number settled on the reservation and, eventually became one of the Confederated Tribes of Warm Springs Indians (Wasco, Wishram, Warm Springs [or Tenino], and Northern Paiute).

Settlement East of the Cascades

Migration of newcomers into Oregon reversed itself after 1860, flowing eastward from the Willamette Valley, back across the Cascades Mountains and the Columbia Plateau along the route of the Oregon Trail. Many of the new settlers were the children of first-generation Oregon pioneers. After passage of the Homestead Act in 1862, they filed upon free lands in the public domain. An increasingly generous federal land policy served as a major stimulus. Most significant of all, however, was the discovery of gold in the upper John Day watershed and in the Blue Mountains. The twin allurements of mining and raising cattle attracted thousands to stake their fortunes in central and eastern Oregon in the latter four decades of the nineteenth century.

The gold rush became the primary factor in drawing both Euro-American settlement and a transient Chinese population to the watershed of the John Day River. Almost overnight, towns and villages appeared after 1862. Some survived; a number vanished. Settlers moved in to raise foodstuffs to supply the miners and to take advantage of other resources. These included grasslands suitable for stock-raising, tillable lands where they could plant crops, and timberlands where they could fell trees to cut into lumber. The region, in spite of its isolation, possessed sufficient magnetism to attract and hold a new population. Estimates suggested a population of between 4,000 and 5,000 residents in the upper John Day watershed by the fall of 1862 (Anonymous 1902: 388).

The establishment of stage lines, operation of a mail route, and the death of Chief Paulina, a leader of the Northern Paiute, in 1867 laid the foundation for a more lasting stability in the region. An early historical account noted conditions by 1869:

On the main John Day river eighty claims had been taken, 9,064 acres were fenced, 3,608 acres were under cultivation. The largest claims fenced contained 400 and 250 acres respectively. Freight rates from The Dalles were from six to ten cents per pound" (Anonymous 1902: 392-393, 395).

Into the 1870s, settlers — the majority from the Ohio Valley and the upland south — spread along the bottomlands of the John Day and its tributary streams. These newcomers adapted to ranching and subsistence agriculture, establishing a viable rural economy that outlived the excitement of the gold rush (Mark 1996: 19-20).

Placer deposits, nonetheless, continued to draw miners once depleted of the easy picking of nuggets and gold dust. Among the miners were hundreds of immigrant Chinese laborers, who poured into the area to engage in back breaking toil moving massive amounts of rock and gravel, diverting water through ditches and flumes, and washing the paydirt to extract profits. Federal census schedules for Grant County's John Day Valley in 1870 and 1880 document a remarkable number of Chinese in the region. The Asian population probably peaked in the 1880s when nearly 1,000 Chinese, ninety-nine percent male, resided in the county. Most were engaged in mining, but some worked as laundrymen, cooks, store owners, and herbal doctors (Barlow and Richardson 1979, 1991; Bureau of the Census 1880).

The Chinese population of the John Day country was repeatedly subjected to persecution. Prejudice ran rampant. Illustrative of attitudes were articles in the Grant County News (John Day, OR.):

Three Chinamen were recently killed by an engine at Bonneville, and the railroad company has settled with the executor of their estates by the payment of $1,000, which establishes $333.33 1/3 as the price of a dead Mongol (Anonymous 1885a, February 19).

To every one it is apparent that the Chinese are a curse and a blight to this county, not only financially, but socially and morally . . . . What the Chinaman wears, he brings from China, and what he eats (except rats and lizards), he brings across the ocean, and thus American trade or production reaps no benefit from his presence (Anonymous 1885b, October 15).

Mr. Yong Bo died at his home in Dry Gulch last week, and was buried by his celestial comrades beneath upwards of six inches of mother earth. These heathen ought to be compelled to plant their diseased carrion deeper (Anonymous 1886, February 4).

Fig. 9. Chang and Lung On, Chinese

residents of Grant County, ca. 1890 (OrHi 26,471).

The Chinese also wrote of their suffering in the stifling, hostile environment of Grant County. "I'm shocked by the message from Lung On that our friend, Mr. Lin, was shot and killed by a barbaric American. Grief come with that news. What a miserable act!," wrote Kwang-chi to Lung On of John Day on February 4, 18[??]. "We are all suffering from the barbarian's serious robbery; we Chinese suffered at the gold mine during several incidents and indirectly they took between $200 and $300," wrote a spokesman for Ton Yick Chuen Company to Lung On on May 18, 1904 (Applegate and O'Donnell 1994: 214-218).

Hostilities Erupt

The sudden rush of gold seekers to central and eastern Oregon exacerbated tensions and heightened the prospects for conflict with native inhabitants. This reality was driven by several factors, chief of which was the slow implementation of treaty policy in the region.

In July, 1862, J. M. Kirkpatrick secured appointment as Special Indian Agent to assess the situation in the country occupied by the Northern Paiutes. Unable to find an interpreter at either Warm Springs or the Umatilla reservations, Kirkpatrick nevertheless set out east over the Oregon Trail to the mines on the Powder River. Along the way, Kirkpatrick found ample evidence of gold rush. "For a distance of over one hundred and forty miles in length, extending from Burnt River basin southwest to the south fork of John Day's river, and from thirty to forty miles in width, a great many men are at work mining, and are making from five to fifty dollars per day each," he wrote. He further noted that lode deposits at the head of the John Day, Powder, and Burnt rivers held promise for more sustained mineral production (ARCIA 1863: 265-267).

During the Civil War years, the Oregon legislature took the initiative to mount military expeditions into Northern Paiute country. Volunteers and soldiers, newly recruited into the Oregon Infantry and Oregon Cavalry as token forces at western Army posts, took the place of Army regulars who had rushed east to serve in Union campaigns. The Oregon Infantry spent nearly seven months on the assignment.

In the spring and summer of 1864, Captains John M. Drake and George B. Curry and Lt.-Col. Charles Drew swept with troops through southeastern Oregon, northern Nevada, and southwestern Idaho. "These tribes can be gathered upon a reservation, controlled, subsisted for a short time, and afterwards be made to subsist themselves," wrote Indian Superintendent J. W. Perit Huntington, "for one-tenth the cost of supporting military force in pursuit of them" (ARCIA 1864: 85). Drew, an avid Indian-hater and promoter of military action against the Northern Paiutes, had published a litany of alleged wrongs perpetrated by the Indians. He sought confrontation with them (ARCIA 1863: 56-60).

Captain Drake began the campaign with 160 enlisted men and seven officers from Fort Dalles, leading them into the Harney Basin in April of that year. His instructions were to protect the miners and explore the country not lying within the Indian reservations. The Northern Paiute had raided both the mining camps at Canyon City and the Warm Springs Reservation in the fall of 1863. Drake was to seek restoration of stolen property and drive the hostile Indians away from the settlements. Indian scouts from the Warm Springs Reservation joined the party when it passed their homes. The soldiers ascended the Deschutes and passed over the trail via the Crooked River. On May 18, while on the Crooked River, an advance patrol encountered hostile Indians. The Indians killed twenty-three soldiers and one of the Indian scouts; they wounded several other men. The Northern Paiutes slipped away before the main command converged on the battle site (Knuth 1964: 5-35).

As Drake's force moved on toward the Harney Basin, patrols of both regular soldiers and Indian scouts from Warm Springs made salients toward the South Fork of the John Day and into the upper river valley to try to locate members of Northern Paiute Chief Paulina's band. They failed. Paulina's people continued to harass travelers and packers on the trail to the mines at Canyon City (Knuth 1964: 50-63). In the Harney Basin the soldiers could find no Indians, but on July 7 learned of their actions to the north where they stole thirty or forty head of horses at Canyon City, killed one or two residents, and ran off stock on Bridge Creek. "They are, from all accounts," wrote Drake, "concealed in the mountains about the head of the South Fork of John Days River" (Knuth 1964: 71).

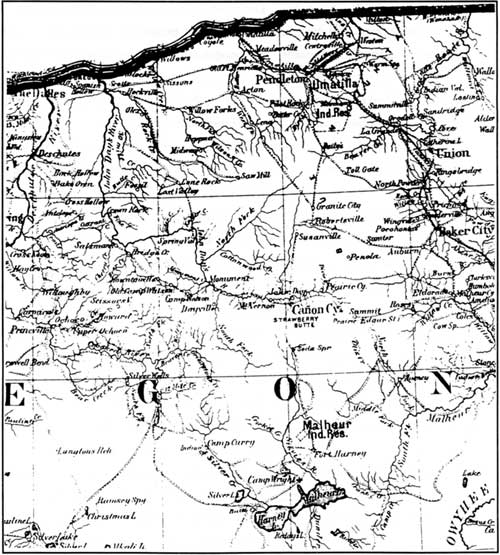

Fig. 10. Drake's 1864 route to "Old Camp

Watson" and "Canyon C[it]y" (Knuth 1964, Map Insert).

The 1864 campaign against the Northern Paiute then shifted north to the mountainous region lying between Harney Basin, the John Day River, and upper Crooked River. Except for a skirmish between the Warm Springs scouts and the hostile Paiutes on July 12, the Oregon Cavalry had little contact or sighting of the Indians. Capt. Drake occupied his days writing his journal and observing the region's geology. On July 16 he noted:

Some soldiers, during the absence of the main body of the troops on the Indian chase, discovered some very fine geological specimens on the crest of a low ridge jutting out from the main chain of the hill opposite our camp. Those specimens consisted of fossil shells imbedded in a hard sand stone. In most cases, the imprint of the shell only is left in the rock; this is very distinct and from appearances I judge the shells to be marine in their character, although I do not feel very confident of it. I went up to the ridge this morning and succeeded in gathering some fine specimens for Mr. [Thomas] Condon at the Dalles, and purpose sending them to him by the next wagon train. It is certainly a great curiosity, and a practical geologist would find a fine field for his profession in delving into the rocky hills of the camp (Knuth 1964: 74-75).

During their patrols in quest of the elusive Indians, the Oregon Cavalry established a number of camps, depots, and temporary forts in central and southeastern Oregon. These posts were established by the Oregon Volunteer Infantry and Oregon Volunteer Cavalry except for Fort Harney, a U.S. Army post. Most were occupied for only a few weeks or a few months (McArthur 1974).

Situated approximately fifteen miles west of the present town of Dayville, Camp Watson was established to protect the well-traveled but vulnerable road from The Dalles to the gold mines at Canyon City, soon to be surveyed as The Dalles-Boise Military Road. In June, 1864, Capt. Richard S. Caldwell, leading Company B of the First Oregon Cavalry and a detachment from Washington Territory, explored the South Fork of the John Day. By July, Caldwell had established Camp Watson at a site on Rock Creek. In the early fall, Caldwell was relieved by Capt. Henry C. Small who relocated Camp Watson to Fort Creek, four miles to the west (Knuth 1964:103-104).

Table 1. Military Establishments in Central Oregon

| Name | Established | Location |

| Camp Maury | May 18, 1864 | T17S, R21E, Sec. 20, W.M., SE side of Maury Creek west of Rimrock Creek, Crook Co. |

| Camp Gibbs | July 21, 1864 | Drake Creek, Crook County |

| Camp Dahlgren | August 22, 1864 | Beaver Creek, Crook County |

| Camp Watson | October 1, 1864 | Five miles west of Antone, Wheeler Co. |

| Camp Logan | Summer, 1865 | Strawberry Creek, six miles south of Prairie City, Grant Co. |

| Camp Currey | August, 1865 | Silver Creek, Harney County |

| Fort Harney | August 16,1867 | Rattlesnake Creek, Harney Co. |

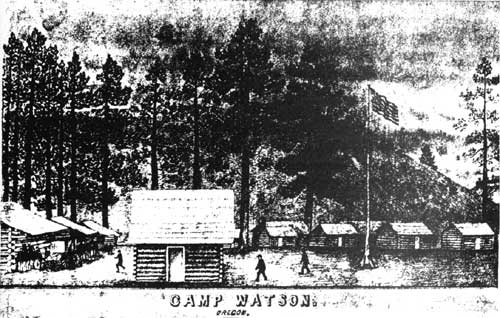

Camp Watson reached fairly respectable physical proportions, arranged around a central quadrangle. Twelve huts for soldiers were aligned on either side of the wagon road at the north end of the quad, with four offers' huts opposite. To the west were a small map house, a hospital, a guard hut and orderly room, and a commissary and quartermaster store. Corrals and stables bordered the east side. All buildings were constructed of logs and roofed with wood shingles. Camp Watson was occupied by the First Oregon Cavalry until May of 1866, and then turned over to the regular army unit its final abandonment in 1869. (Kenny 1957: 4-16).

Tensions in the region did not abate with the military missions. Between September, 1865, and August, 1867, numerous incidents occurred which involved Northern Paiutes and residents of the upper John Day watershed. These ranged from armed encounters and killings to petty thieving, raids of isolated ranches and mining camps, and periodic sweeps by volunteer companies seeking the "enemy." Indian Superintendent Huntington summarized eight packed pages of these encounters in his report to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1867 (ARCIA 1867: 95-103). Indians suffered numerous deaths; stock drivers lost their animals and cursed the Indians. Indians raided settlements and escaped. Troops rounded up Indians and killed them. The situation was nearly guerilla warfare.

Fig. 11 Sketch labeled Camp Watson, n.d.

(OHS Collections)

Resolution of conflicts with the Northern Paiute, of a sort, came with the executive order of President Ulysses S. Grant on September 12, 1872, to create the Malheur Reservation. A vast tract sprawling across the meadows of the Harney Basin and encompassing Malheur Lake, Oregon's largest lake, the reservation was designated as a permanent homeland for the Northern Paiute. It was enlarged on May 15, 1875, to 1.7 million acres, but pressures mounted rapidly for its termination. On January 28, 1876, the president virtually abolished the reservation. Cattle drovers such as Peter French and David Shirk had discerned the potentials for wealth if they controlled key water resources and grazing. The press was on to dismember the Malheur Reservation. For the Northern Paiute the decision was a disaster. They would survive, largely landless, until securing individual, public domain allotments in 1897 and in obtaining in 1935 the Burns Paiute Indian Colony, a tract of 760.32 acres near Burns, Oregon. They also retained ten acres at old Fort Harney (Ruby and Brown 1986: 9,158-159).

A last scare of Indian hostilities swept through the John Day Valley in 1878 with the outbreak of the Bannock War. The troubles erupted in Idaho because of trespass by sheepherders onto Indian lands. The Bannock swept into eastern Oregon to rally the discontented Northern Paiute. The efforts to forge common cause against the Euro-Americans largely failed. Following a brisk battle at Silver Creek on June 23, the Bannock turned north toward the Columbia River to escape soldiers of the U.S. Army. They engaged in an abbreviated exchange near Canyon City, killing one man and wounding two others. The Bannocks moved from the South Fork of the John Day to the Long Creek Valley, stealing, burning cabins, and fleeing. The final conflicts occurred at Willow Springs and Birch Creek. The Umatilla Indians did not rally and, in fact, joined in opposing the Bannocks and killed Egan, a Northern Paiute leader who was with the hostile forces. The continued pursuit compelled some Bannocks to try to cross the Columbia. Their war was crushed with many deaths; the Bureau of Indian Affairs removed the survivors to the small reservation at Fort Hall, Idaho (Ruby and Brown 1986: 8-9; Brimlow 1938).

The Bannock War of 1878 contributed to considerable local lore about Indian hostilities in the John Day watershed. Because of settlement, many Euro Americans had personal stories to tell. Families fled isolated homesteads and residences, forted up at defensible positions, and waited for the troubles to subside. The Dedman homestead near Twickenham was one of these locations. Built of hewn logs with heavily shuttered windows, the building had holes in its walls for rifle ports. A. S. MacAllister and Peasley owned the ranch in the 1870s. It subsequently passed to Zachary Keys in 1906. An account by Dickse Williams summarized the fate of most of the "forts" of the era of Indian hostilities: "As far as can be determined, the [Dedman] house was never under attack by Indians . . " (Oregon Society Daughters of the American Revolution 1959: 28-29).

Settlement Patterns and Land Programs

Several federal land policies shaped the pattern and course of settlement in the John Day watershed. First was the removal of Indian title. This was ultimately accomplished through treaties of land cession with the tribes of the region: Treaty with the Walla-Walla and Cayuse (June 9,1855, ratified March 8, 1859), Treaty with the Nez Perces (June 11, 1855, ratified March 8, 1859), Treaty with the Tribes of Middle Oregon (June 25, 1855, ratified March 8,1859), Treaty with the Nez Perces (June 9,1863, ratified April 27, 1867), and Treaty with the Snake (August 12, 1865, ratified July 5, 1866). These agreements ceded millions of acres to the United States and provided for reservations or the removal of tribes to other existing reservations (Kappler 1904: 694-698, 702-706, 714-719, 843-848, 876-878).

Pivotal among the federal land programs in the John Day region was the massive government grant of hundreds of thousands of acres to The Dalles-Boise Military Wagon Road Company. In 1874, that firm and its successor purchasers formally secured odd-numbered sections, three square miles to either side of each mile of road right-of-way. This cut a swath through the John Day region, including portions of present-day Monument lands. The company wanted to sell some lands and hold onto others. Its policies clearly impacted where and when people would settle, for it controlled the price, acreage, and date of sales.

Fig. 12. Fertile bottomlands near

Prairie City secured by owners of grant to The Dalles-Boise Military

Road, ca. 1910 (OrHi ODOT 2186H).

In general, the United States followed an increasingly generous land policy in the nineteenth century and, by mid-century, Congress engaged in outright give-aways of the public domain. The creation of military bounties was an old system that had emerged during the colonial period and continued. It was a means for the government to pay soldiers who had served the public interest in time of war. The War of 1812 and the Mexican War both led to laws which promised lands to veterans. The Act of 1847 permitted the issue of warrants to individuals for 40 or for 160 acre parcels. These warrants, along with old ones outstanding from the War of 1812, were dumped onto the market and discounted, encouraging speculators as well as veterans to move west. The Bounty Land Act of 1850 granted 80 to 160 acres to officers and soldiers who had served four to nine months, or who had served in wars since 1790 but had not previously secured a land grant (Gates 1968: 173-174; 270-272).

The Homestead Act of 1862 entitled any person who was head of a family or twenty-one years old (citizens, or those who had made a declaration of citizenship intent) to file on 80 acres at $2.50/acre or 160 acres at $1.25/acre. The claimant had to pay a $10 filing fee and two subsequent fees each of $4. If this person met the terms of proof, namely that they resided on the land and it was surveyed by the General Land Office, between the fifth and seventh year they could secure title merely for the fees. If claimants wanted to expedite the patent, they could pay the acreage fee and, if the land was surveyed, obtain the deed. Paul Gates, historian of federal land laws, commented: "The Homestead Act breathed the spirit of the West, with its optimism, its courage, its generosity and its willingness to do hard work ..." (Gates 1968: 394-395).

If a person wanted to speculate in land, or anticipated its immediate development and wanted to subdivide it, the General Land Office would sell public lands at $1 .25 per acre to cash purchasers. In a sense then, the cash entry system, the Homestead Act, and grants to military wagon roads and railroads worked in competition. Wagon road companies had to set their land prices at affordable rates. Since their grants were part of a vast checkerboard of alternate sections, their routes opened to settlement government lands as well as their own. This proved a mixed blessing for those seeking profits (Gates 1968).

The largess of Congress continued. The General Land Office used another measure for settlers on the Columbia Plateau to obtain land. The Desert Land Act (1877) permitted filing on up to 640 acres of non-timbered, non-mineral land not producing grass. Claimants paid $.25 cents an acre on filing and, within three years, if they could prove they had irrigated the land, they could secure title by paying another $1.00 an acre. In time 159,704 claimants filed on 38.2 million acres under the law; the General Land Office issued deeds to 8.6 million acres under the law in Oregon and the other ten western states where it applied (Gates 1968: 401).

The Enlarged Homestead Act (1909) permitted settlers to file upon an additional 320 acres beyond their initial claim. The rationale was to help create farms in arid regions of sufficient size to sustain livestock operations (Gates 1968: 504-505).

The Stock Raising Homestead Act (1916) permitted filing on an additional 640 acres of the public domain. The argument driving this law was that most of the prime lands had already been taken but to survive and prosper, stock raisers needed a larger land base. The law permitted filing on land "chiefly valuable for grazing and raising forage crops" and not susceptible to irrigation from any known source. Within its first decade of operation in the American West, the law attracted 114,896 claimants who filed on 45.6 million acres (Gates 1968: 516-520).

Through its various land programs, Congress encouraged sustained Euro-American settlement in the John Day basin. It passed laws which facilitated the development of range industries, and it gave generously from the public domain to encourage raisers of cattle, sheep, and horses to try their fortunes in the John Day watershed. (Anonymous 1902: 394). Bureau of the Census records on the course of agricultural development in the John Day watershed document a steady build-up of farm acreages between 1870 and 1950. In the latter half of the twentieth century, there were declines in the numbers of acres in farms because some owners abandoned farming as an activity and some reforested their lands and moved from grazing into timber production.

Table 2. Acreage in Farms, Grant and Wheeler Counties

| 1870 | 1890 | 1910 | 1930 | 1950 | 1979 | 1987 | |

| Grant County | 18,177 | 199,590 | 445,170 | 899,329 | 1,074,351 | 1,072,852 | 1,020,786 |

| Wheeler County | NA | NA | 415,576 | 688,056 | 819,400 | 729,800 | 766,422 |

(Bureau of the Census 1895, 1913, 1952)

The actual number of farms in Grant and Wheeler counties increased until 1910 and then began a generally downward trend. An important part of the trend was the consolidation of holdings. Persons with capital bought out owners of small farms and consolidated the acreage into larger management units.

Table 3. Number of Farms, Grant and Wheeler Counties

| 1870 | 1890 | 1910 | 1930 | 1950 | 1979 | 1987 | |

| Grant County | 99 | 624 | 773 | 632 | 426 | 286 | 402 |

| Wheeler County | NA | NA | 387 | 284 | 189 | 110 | 130 |

(Bureau of the Census 1872, 1895, 1913, 1932, 1952)

Early Settlement in the Vicinity of the National Monument

Records of the General Land Office and its successor, the Bureau of Land Management, confirm the significant impact of the Dalles-Boise Military Road land grant on settlement both within and in the vicinity of the present-day Monument. In 1874, the grant's alternate, odd-numbered sections removed from public entry hundreds of thousands of acres. This was especially true in the Painted Hills Unit where the wagon road passed through the watershed of Bridge Creek. The early land records further confirm that when local settlers attempted to use the Homestead Act to secure lands within the bounds of what is now the National Monument, they often did not succeed. Many relinquished their claims or had them cancelled by the General Land Office.

Sheep Rock Unit

Bisected by the John Day River, the Sheep Rock Unit lies north of Picture Gorge in Grant County, with tracts in T10, 11, and 12S, R26E, W.M. It includes arid mountain slopes, and the rich bottomlands of Turtle Cove, including the secluded valleys of Big Basin and Butler Basin. Settlement came particularly late to this inaccessible area. The first Euro-American resident is said to have been Frank Butler, a one-armed rancher who built a cabin and gave his name to Butler Basin in 1877 (McArthur 1974: 98-99).

Early settlers used several congressional programs to secure lands here. For instance, Mathias Howe, used the cash entry system to purchase 160 acres in 1876 in Section 20, T12S, R26E, W.M. In 1898, Floyd Officer secured a homestead patent to 160 acres in Section 6 in the Butler Basin. Sylvia Officer obtained a patent to forty acres under the Desert Land Act in Section 18 of this township. The odd-numbered sections — 5, 7, and 17 — were part of the grant to The Dalles-Boise Military Wagon Road Company. Because these patents were not confirmed until 1900 and 1901, it is probable that the tracts remained unsettled (though probably used for grazing) until issue of the deeds (BLM n.d.a, n.d.b, n.d.c).

BLM Master Title Plats, Historical Index, and Control Data Inventory confirm grants and filings on lands within the Sheep Rock Unit, as given below. Claims filed under the Homestead Act which were later relinquished are not identified by name in the Control Data Inventory; only the serial number and dates of filing and relinquishment are preserved.

T10S, R26E, W.M.

Section 31 160 acres in NENW, SENW, NESW, SESW were filed upon 11/04/1893 under the Homestead Act; the claim was cancelled 4/29/1904.

Section 31 Peter J. Morrison purchased 80 acres, NESW, SESW on April 11, 1910.

(BLM n.d.p, n.d.q, n.d.r)

T11S, R26E, W.M.

Section 20 Ransom Glaze secured patent on 8/12/1901 under the Homestead Act to NESW, NWSW, and SWSW.

Section 30 Ebon Officer secured patent on 12/01/1898 under the Homestead Act to SENW, NESW, SESW.

Section 30 A claimant under the Desert Land Act sought the NWSW and the NWSE on 11/23/1898; the claim was cancelled on 7/17/1905.

Section 31 Ebon Officer secured patent on 12/01/1898 under the Homestead Act to NENW.

Section 31 Finlay Morrison secured patent on 1/27/1904 to 159.06 acres under the Homestead Act in SENW, NESW, SWSW, and SESW.

Section 32 A claimant under the Homestead Act filed on the SENE on 2/14/1906; the claim was cancelled on 5/19/1913.

(BLM n.d.s, n.d.t, n.d.u)

T12S, R26E, W.M.

Section 6 Floyd Officer secured patent on 1/30/1898 to 160 acres in NENW, SENW, NESW, and, NWSE.

Section 6 Floyd Officer secured patent as a Desert Land Entry on 8/16/1906 to 157.41 acres in SESW, SWSE.

Section 7 All of this section was granted to The Dalles-Boise Wagon Road Company and patented 12/03/1901.

Section 17 All of this section was granted to The Dalles-Boise Wagon Road Company and patented 12/03/1901.

Section 18 Sylvia Officer secured patent as a Desert Land Entry on 9/21/1908 to 40 acres in NENE.

Section 30 A claimant under the Homestead Act filed on the NENE, NWNE, SENW, NESW on 2/23/1895; the claim was cancelled on 7/6/1896.

Section 30 A claimant under the Homestead Act filed on 7/8/1893 on the NWNE, SWNE, SENW, and NESW under the Homestead Act; the claim was cancelled on 3/14/1900.

(BLM n.d.a, n.d.b, n.d.c)

The first family to establish ranching operations in Butler Basin was the Officer family. Eli Casey Officer was the son of first-generation Willamette Valley pioneers. In 1861, he had migrated with his brother back across the Cascades, bringing some of the first sheep to the John Day valley. Members of his large, extended family were instrumental in the organization and early development of Grant County. Eli Officer raised both cattle and sheep on his homestead near Dayville until 1881, when according to family tradition, he moved to Butler Basin (Murray 1984b: 1-4; Taylor and Gilbert 1996: 21). BLM records, presented above, do not indicate that Eli formally secured any land there, but son Floyd, and Ebon Officer did secure patents to lands in Butler Basin under the Homestead Act.

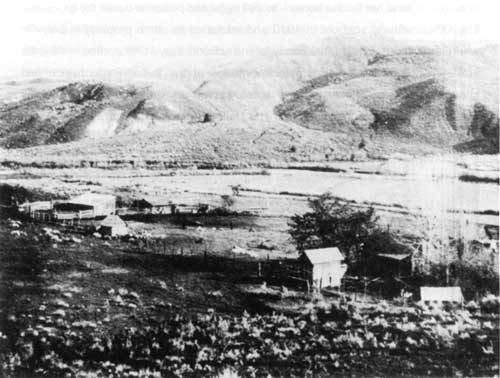

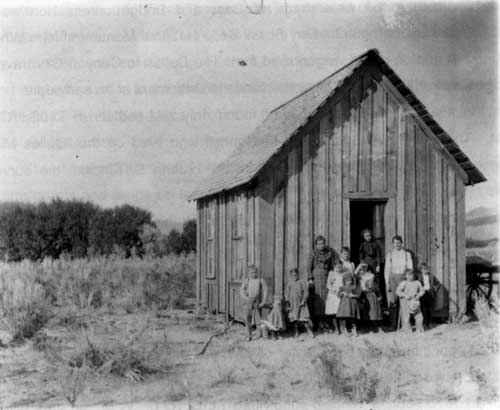

Fig. 13. Structures and landscape

features on the Floyd Officer homestead, ca. 1900 (JDNM Catalog

#2736)

One of nine children of Eli and Martha (Thorpe) Officer, Floyd Lee Officer was born and raised in the Dayville area. From December of 1890, Floyd homesteaded his own land in Butler Basin. He worked the land, for seven years, and secured patent to the 160-acre Butler Basin homestead in January of 1898 (Murray 1984b: 4). That same year, he married Sylvia Fitzgerald Officer, and together they raised eight children, living a rudimentary, hardscrabble existence. Twice a year Floyd went to The Dalles for supplies. His journeys sometimes lasted up to six weeks. Sylvia Officer rode horseback to Dayville — a child in front and child behind her on the horse — to sell eggs and butter or barter for groceries. The Officers finally sold out in 1910 and relocated to ranch property in Dayville where the children could more easily attend school. Floyd Officer died in Dayville in 1948. Because of his intimate knowledge of the Butler Basin region and interest in fossils, Officer several times served as local guide for Thomas Condon, pioneer paleontologist from The Dalles (Ashton n.d. ; Murray 1984b).

After 1919, the Sheep Rock area became home to a sizable ethnic community of immigrants from Scotland. Reared in a country of limited land and resources, with a restless yearning for economic opportunity, several men and women immigrated from Scotland to the upper John Day country at the end of the nineteenth century. Family surnames — Finlayson, MacKay, MacBain, McRae, Cant, Murray, Munro, and Frazier — confirmed their Scottish origins. An estimated 130 families with Scottish origins settled in the district served by the crossroads community of Dayville. The brogue of their English, their knowledge of Gaelic, familiarity with sheep raising, willingness to engage in hard work, and love of dancing provided a unique character to their community (Murray 1984a: 15-16).

Arriving from Scotland in 1905, James Cant Sr. worked on ranches in the area and, over several years, built up his sheep holdings by taking half of the annual production of lambs in lieu of salary. Cant married Elizabeth Grant, also from Scotland, in 1908. With his partner Johnny Mason, Cant purchased the Floyd and Sylvia Officer place in 1910. For some six decades, the Cant family continued to improve and expand their property as their ranching operation grew and evolved from sheep to cattle. By the mid-i 970s, when the property was acquired by the National Park Service, the Cant Ranch had long been known as one of the most extensive, long-lived operations in the vicinity of the Monument (Toothman 1983).

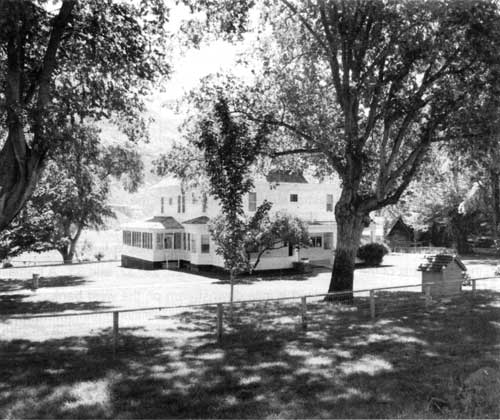

Fig. 14. Home of James and Elizabeth

Cant, erected 1917-18; F.K. Lentz, 1996 (National Park

Service).

When the Cants acquired the Officer homestead, they used many of its existing structures and improvements. These included the corral, orchard, irrigation system, fields, and buildings. Between 1915 and 1918, the Cants hired workmen to construct a commodious new ranch house, based on designs from The Radford American Homes, a popular pattern book (1903).

The new Cant house became a familiar landmark to travelers with the building of the highway in the early 1920s through Picture Gorge. People on the road often stopped for food and drink and sometimes for a room. The ranch complex grew in the 1920s with construction of a garage, barn, sheep-shearing sheds, watchman's hut, and a shed to house the Kohler light-plant. By the 1930s, the Cant Ranch headquarters included some sixteen buildings, corrals, gardens, orchards, irrigation systems, and fields (Taylor and Gilbert 1996: 7, 27-51).

Clarno Unit

The Clarno Unit is located east of the John Day River and north of Pine Creek in T7S, R19E, W.M. Iron Mountain runs diagonally through the center of the township. The tract lies near the eastern border of Wheeler County, close to the Wasco County line.

Settlement in the vicinity of Clarno concentrated along the river corridor to the west and commenced in the late 1860s, with the arrival of the Andrew and Eleanor Clarno family. Cadastral surveyors subdivided the township in October, 1873. At that time they noted the farms of "Matier" [Mettur] and Joseph Huntley on Pine Creek in sections 33-34 and 35. Huntley also had a large, fenced field on the east bank of the John Day River in sections 28, 29, 32, and 33. A partially fenced field lay in the bottomland a mile downstream on the west bank (Perkins 1873).

The cadastral survey plat of 1873 indicates that the cabins of George Mettur or "Matier" and Joseph Huntley lay just outside of the lands now within the National Monument. Huntley's house was on the south bank of Pine Creek. In 1880, George J. Mettur (Matier) purchased 120 acres in Section 34, the first deed issued in the township. Joseph Huntley did not secure his homestead patent until 1891.

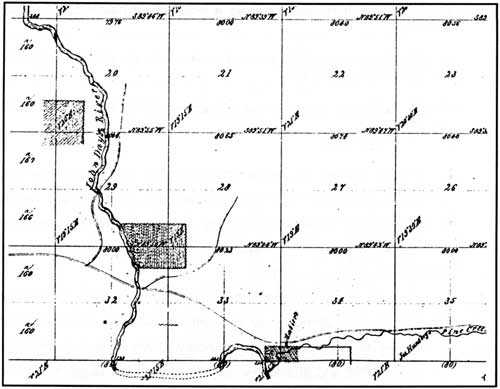

Fig. 15. House locations of Joseph

Huntley and Matier (Mettur) on Pine Creek, 1873 (Perkins

1873).

The BLM Master Title Plat, Historical Index, and Control Data Inventory confirm grants and filings on lands within the Clarno Unit, as given below. Claims filed under the Homestead Act which were later relinquished are not identified by name in the Control Data Inventory; only the serial number and dates of filing and relinquishment are preserved.

T7S, R19E, W.M.

Section 23 All of the SW 1/4 was filed upon 11/4/1901 under the Homestead Act; the claim was relinquished 11/02/1909.

Section 34 George Mettur purchased 120 acres, SWSW, SESW, and SWSE on 6/1/1880.

Section 34 Joseph Huntley secured a Homestead patent to SESE on 10/21/1891.

Section 35 Joseph Huntley secured a Homestead patent to SWSW, SESW, SWSE on 10/21/1891.

Section 35 Edward Lee purchased 120 acres, NESE, NWSE, and SESE on 10/02/1891.

(BLM n.d.d, n.d.e, n.d.f)

The especially rugged nature of this township precluded extensive settlement. Between 1887 and 1912 the General Land Office logged twenty cancellations on claims and issued sixteen deeds. More than half who attempted to settle failed to meet the terms of proof under either the Homestead Act or the Desert Land Act (BLM n.d.d, n.d.e, n.d.f).

Although their lands lay outside the boundaries of the present-day Clarno Unit of the Monument, the Clarno family was among the most successful and long-lived of ranching families in the area. Andrew Clarno first examined the John Day country in 1866 and, the following year, moved his large family and 300 head of cattle from Eugene to land on the Wasco County side (west bank) of the John Day River, one-half mile downstream from the present-day crossing of SR 218. The Clarnos operated a ferry crossing where the bridge now stands, and gave their name to the locality where a school, post office, hotel, and grange hall were established at various times over the next several decades (Campbell 1976:13-14).

The Clarno family lived in a log cabin for a year before constructing a permanent home. Son John Clarno, a skilled teamster at age eighteen, was dispatched to pick up a double wagon load of milled lumber at The Dalles and haul it to the homestead with a team of twenty-four oxen (Campbell 1976: 15-22). On a site near the river, they built a home of plank box construction, with wrought iron nails and a full-width front porch. Little is known of the physical development of the ranch. The family put in a garden, maintained a fruit orchard, and raised fine horses. The Clarno cattle ranching operation was renowned, and financially prosperous. Clarno cattle were trailed to Union Pacific Railroad railheads in Utah, Wyoming, and Nevada. As many as fifteen cowhands were employed during round-ups, and over 100 saddle horses were raised for use on the ranch (Campbell 1976: 21-23).

Fig. 16. Clarno School, moved ca. 1893

from from a site on Sorefoot Creek to the Andrew Clarno homestead, n.d.

(OrHi 66175)

The family holdings grew as the children reached adulthood. In 1881, son John W. Clarno completed residency and proof to obtain a homestead patent to 160 acres in Section 32 on the Wheeler County side of the river. For reasons uncertain, Andrew Clarno did not receive patent to his original homestead until 1889 (Campbell 1976: 14). Andrew and son Charles Clarno both purchased additional lands in this vicinity in 1889 and 1890. In 1912, John Clarno sold his parents' original homestead, signaling the end of a colorful era in local history (Campbell 1967:14, 88).

Painted Hills Unit

Situated in the watersheds of Bear and Bridge creeks northwest of Mitchell, this unit of the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument is in Wheeler County. A portion of the wagon road from The Dalles to Canyon City traversed Bridge Creek, thus opening its bottomlands to settlement at an early date.

In 1872, a cadastral surveyor found only two settlers in T10S, R20 E, W.M. These were Al Sutton and McConnell who lived on the "Dalles Military Wagon Road" in the Bridge Creek drainage. John S. Kincaid, the surveyor, wrote:

There is a small quantity of good land in this township, chiefly situated along John Days River and Bridge creek, but without frequent irrigation it is comparatively worthless in an agricultural point of view. The general surface of the Township is very hilly. It is well watered by John Days River and its tributaries (Kincaid 1872).

He referred to Bridge Creek as a "small stream with a rapid current". Sutton secured appointment as postmaster of Bridge Creek post office on July 2,1868; the station closed on January 20,1882 (Fussner 1975: 23; Landis 1969: 9).

In 1873 John S. Kincaid subdivided T11S, R21E, W.M., an area bisected by Bridge Creek and through which passed The Dalles-Boise Military Road. Here Kincaid noted the presence of early settlers Christian A. Myers, James Curry, McGarth, and Thomas Caton. He noted an unidentified claim with a fenced field in Section 5, subsequently part of the National Monument. Jesse L. Miner secured a homestead patent to this tract later, in 1899 (Kincaid 1873; BLM n.d.g, n.d.h, n.d.i).

In 1881 Fullerton, cadastral surveyor, found only one settler in T11S, R20E, W.M. This was S. A. Lawrence who resided in Section 25, more than three miles due south from subsequent National Monument lands. Fullerton noted: "There is but little land in this Township susceptible of cultivation, though it is totally well adapted to grazing purposes." Fullerton was aware of the fossil deposits. He continued: "This Township [is] composed of slate rock which bears the imprint of various kinds of leaves to a very perfect degree" (Fullerton 1881).

In 1880, surveyor Aaron F. York subdivided T10S, R21E, W.M. York found only one settler in the entire township: "Sam'l Carrol." The Carroll house stood east of The Dalles Military Road in the SE 1/4 of Section 31, some distance east of Bridge Creek.

BLM Master Title Plat, Historical Index, and the Control Data Inventory confirm grants and filings on lands within the Painted Hills Unit, as given below. Claims filed under the Homestead Act which were later relinquished are not identified by name in the Control Data Inventory; only the serial number and dates of filing and relinquishment are preserved.

T11S, R20E, W.M.

Section 1 All of this section was granted to The Dalles-Boise Wagon Road Company and patented 12/03/1901.

Section 2 All of this section was filed upon 11/15/1920 under the Stock Raising Homestead Act; it was relinquished on 11/30/1921.

Section 2 All of this section was filed upon 1/6/1922 under the Stock Raising Homestead Act; it was relinquished on 8/22/1923.

Section 11 All of this section was granted to The Dalles-Boise Wagon Road Company and patented 11/17/1900.

(BLM n.d.j, n.d.k, n.d.l)

T11S, R21E, W.M.

Section 5 All of this section was granted to The Dalles-Boise Wagon Road Company and patented 4/18/1900.

Section 6 160.74 acres in SENE, NESE, and SESE were patented as a Homestead to Jesse L. Miner on 2/25/1899.

Section 6 160.62 acres in SWNE, NWSE, SWSE were filed upon 9/20/1916 under the Homestead Act; the claim was relinquished 2/23/1917.

Section 7 All of this section was granted to The Dalles-Boise Wagon Road Company and patented 11/17/1900.

(BLM n.d.g, n.d.h, n.d.i)

T10S, R20E, W.M.

Section 36 All of this section was a School Grant to the State of Oregon on 2/14/1859.

(BLM n.d.m, n.d.n, n.d.o)

T10S, R21E. W.M

Section 31 160 acres in the SSE, NWSE, and SWNE were patented as a Homestead to Samuel Carroll on 22/1/96.

(BLM n.d.v, n.d.w, n.d.x)

In 1868 Samuel Carroll and his family settled on Bridge Creek in view of the colorful formation now called Carroll Rim. Carroll lands occupied much of the area now within the present-day visitor center at Painted Hills. In 1971, grandson George Carroll reported, "I used to irrigate alfalfa where the Painted Hills state park ground is, on part of the Carroll place. On the Painted Hills I learned to ride my first bicycle — just took it up one of those steep, colored slopes, got on it and let it go" (Brogan 1972: 266).

Samuel Carrol and his wife reared twelve children on their ranch and grazed sheep in the nearby mountains. Like others in the region during the Bannock War scare of 1878, the Carrolls fortified their property. Phil Brogan, historian of central Oregon, later wrote: "Fearing further Indian attacks, Samuel Carroll built a small fort, using blocks of limestone he had sawed from a quarry. In the 1880s, the Carrolls razed the fort and used the stones to build fireplaces and irrigation dams." With the opening of stage connections between The Dalles and Canyon City, the Carrolls served freighters and travelers, by maintaining the road, and charging tolls. A flashflood in 1884 tore down Bridge Creek and overtook the Carroll home. A daughter and three grandchildren of the Carrolls perished (Brogan 1972: 258-261).

The Carroll family of the Painted Hills lived like hundreds of other families in the John Day country in the last half of the nineteenth century. They eked out an existence. They secured meat by raising livestock and by hunting deer. They raised vegetables in a garden irrigated by Bridge Creek. They raised grain and harvested wheat for bread. They tanned hides and made moccasins and shoestrings. They set out orchards and raised fruit. Because of the alkaline water, they made cider vinegar and treated the water with it and sugar (Brogan 1972: 261-263).

In spite of isolation, the Carrolls and others living along Bridge Creek were connected to the outside world. In 1899, an expedition of students led by Prof. John Merriam from the University of California camped in the area to excavate for fossils. In 1902, the men in the family cut juniper poles and helped stretch the first telephone line up Bridge Creek. After 1900, family members began to leave the area, and the ranch was sold to the Hudspeth firm of Prineville after World War Two (Brogan 1972: 264, 267-268). None of the ranch buildings are extant.

Subsistence Living

For decades, those who settled in the John Day country, or those who were born into families residing in that region, shared basic elements of a recognizable lifestyle. Almost all, particularly those living in rural areas but even those living in small towns, engaged in unceasing labors for survival. They lived close to the land, knew and used its potentials, and confronted numerous challenges. Weather — the heat of summer and bitter cold of winter — and flash floods, lightning strikes, falling rocks, forest and prairie fires, rattlesnakes, and rabid animals were realities they had to confront and endure. Illnesses and lack of professional medical care catapulted home doctoring and nursing to a higher significance than in other parts of the region. Life, for a long time and for some a lifetime, was a scramble and a test.

Isolation was a common feature for the scattered residents of Grant and Wheeler counties. Until the 1910s, most of the region was linked to the outside world only by a system of trails and rudimentary wagon roads. Lack of electricity and telephone lines perpetuated isolation far longer than in other areas. Residents used candles, kerosene lamps, carbide lamps, and their own electrical plants. Larger ranches such as that of James and Elizabeth Cant by the 1910s had their own generators to provide a few hours of electricity each day to run shearing equipment, operate electric lights or, by the 1920s, to power a radio. "Yeah, we spent lonely days," recalled Rhys Humphreys, "but we didn't know any better. It was lonely here; the only people that we ever visited was neighbors" (Humphreys 1984a: 4, 21). Isolation for some was a function of labor. The dozens of men who tended sheep and prospectors and miners frequently lived alone or far from society for days and weeks.

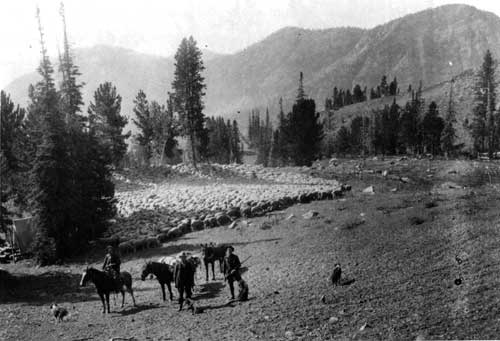

Fig. 17. Herders with flocks at summer

pasture in the mountains of Eastern Oregon, ca. 1915 (OrHi 5,

139).

Daily labors in an era of subsistence living were often gender specific. Women customarily carried nearly total responsibility for maintaining the household and child-rearing. Their tasks — backbreaking and monotonous — involved cooking, washing, mending, making clothing, food preservation, and cleaning. They planted and weeded vegetable gardens, drove away birds and rabbits, picked foodstuffs, dried and parched foods, canned dozens of pints and quarts of home-grown fruit and vegetables, and recycled materials. Their fingers turned old clothing into quilts and rag rugs. They watered stove ashes in hoppers to make lye to process fat and bacon grease into soap. They raised chickens and collected eggs and milked cows and made butter. Any surpluses they carried to town to barter for dry goods and staples. They worked constantly and lived frugally (Jackson 1984: 24-25; Murray 1984a: 64).

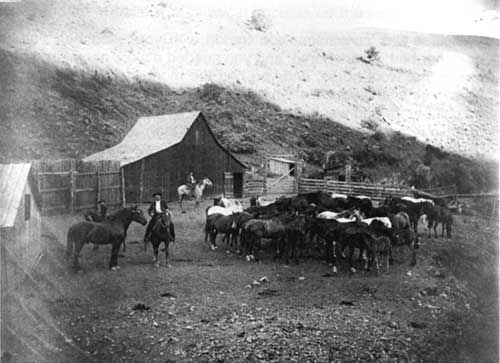

Fig. 18. Ranch house of the Henry

Wheeler family, on SR 207 between Service Creek and Mitchell, one mile

south of Twickenham junction Ca 1910 (Courtesy Fossil Museum)

Men shouldered other responsibilities. They cut, hauled, and stacked wood to fire cook stoves and heat dwellings. In winter they sawed blocks of ice and hauled them to insulated ice houses for use in subsequent months for food preservation and for cooling beverages. They dug cellars, lined them with stone, and filled bins with potatoes, turnips, and apples wrapped in newspapers. Hard labor duties for men included stock tending, sheep shearing, branding, fence construction and maintenance, building houses and barns, blacksmithing, moving herds to markets, and digging ditches. Irrigation was critical in an arid environment. Men hand-dug canals and ditches, planted willows, locust, and poplar along their courses to stabilize their banks, and worked each year to clean the ditches of slide debris and weeds and to repair washouts. Men repaired wagons, harness, mowing machines, plows, harrows, and tools. They hauled foodstuffs in wagons, on pack teams, in touring cars, and in trucks. They changed oil and gaskets, repaired flat tires, and rebuilt engines (Cant and Cant 1984: 21-22; Jackson 1984: 22; Murray 1984a: 38, 60-66; Murray 1984b: 2).

Fig. 19. Men at work on the Bob Wright

on the Parrish Creek Ranch, n.d. (Courtesy Fossil Museum).

Men also contributed to the family diet by hunting, fishing, planting, and pruning fruit trees as well as butchering cattle, sheep, and hogs. They constructed smokehouses and tended fires to preserve meat as jerky and hams. Some worked with their wives to stuff intestines with ground meat fragments and spices to make sausage or head cheese. They hauled wheat to grist mills and brought home flour and corn meal. They tilled the vegetable patch and helped guard the plantings from hungry deer and rabbits. They tanned hides and bartered with Indians from the Warm Springs Reservation for gloves and moccasins. When they lacked cash, a common occurrence, they bartered labor, goods. and livestock for necessary commodities, tools, or food (Cant and Cant 1984: 28; Humphreys 1984b: 25; Murray 1984a: 29-30).

John Murray, a lifetime resident of the area, described the common barter system:

Well, if it was convenient you traded with your neighbor, yes. If your neighbor had a work horse, and you needed a work horse, and he wanted to sell that work horse, and you had the money, you could buy the work horse, or vice versa, or whatever. Or if you had an extra piece of machinery, or you wanted to buy a piece of machinery, and he happened to have it, and if you could buy it cheaper than you could buy it new, why you bought it because you didn't have any money anyhow (Murray 1984a: 29).

The residents of the upper John Day region were perhaps less affected by the impact of the Great Depression. Most lived frugally and had the means to survive through their own hard work. Many raised or procured large amounts of their own foodstuffs. None had high expectations. In several instances young adults remained at home a few years longer, securing housing from their parents and helping work the ranch. The Grant County Bank in John Day, a central point of deposit and loans for many, was shored up by the Oliver family and others and remained solvent, closing only for the national Bank Holiday. Its stability provided a security for the residents of the region not experienced by millions of Americans in other parts of the country (Humphreys 1984a: 26; Murray 1984a: 37).

Subsistence living demanded hard work but it engendered satisfaction. Through the first half of the twentieth century, the rural population of Grant County and Wheeler County remained sparse but relatively constant (Mark 1996: 28). Those who stayed were satisfied with their lot, and considered living in the region with its stark beauty and personal freedom a sufficient reward for confronting its daily challenges.

Cultural Resources Summary

Because of its isolation, some corners of the John Day basin witnessed a period of subsistence-level settlement that lasted from the early 1860s to the turn of the century and beyond. Early ranching and farming activities altered the landscape, and left a pattern of physical imprints on the land different from that imposed by native peoples. Cultural resources associated with settlement in the area are not limited to buildings and structures, but will likely include more ephemeral remnants such as ornamental vegetation, irrigation system features, and abandoned farming equipment.

Homesteads in the vicinity of the Monument clung to the bottomlands of the river and its tributary streams where water was available for domestic and agricultural purposes. On individual homesteads, rudimentary wood structures and corrals clustered near natural springs and native groves of black cottonwoods. The farmsteads were oriented for maximum protection from sun and winter storms.

Arable land was limited to the narrow river plain. Settlers broke the land for cultivation, first in a limited way with gardens, orchards, and shade trees, and later with fields of grain or hay to supplement the feeding of livestock. Irrigation was a necessity in the semi-arid climate. Settlers built hand-dug ditches — main lines and laterals — providing gravity feed systems that served the long, linear fields along the river corridor. The early settlers of John Day primarily ran cattle and sheep operations, so the physical impact of each family's presence extended to range lands miles from the homestead's headquarters. By 1900, native bunch grasses had largely disappeared due to overgrazing, and cheatgrass and other weeds grew in its place. Increasingly, fencing segmented the open range (Strong 1940: 274).

Fig. 20. Original T.B. Hoover Cabin on

Hoover Creek, vicinity of Fossil, 1927 (Courtesy Fossil

Museum)

Only one cultural resource within the boundaries of the Monument (or within all of Grant and Wheeler counties) associated with the theme of settlement is listed in the National Register of Historic Places:

The Cant Ranch, established as the Officer Homestead ca. 1890.Oregon State Inventory of Historic Places listings from Grant and Wheeler counties (encompassing listings in both Umatilla and Malheur National Forests)

Oregon State Inventory of Historic Places listings from Grant and Wheeler counties (encompassing listings in both Umatilla and Malheur National Forests) include the following examples of rural settlement:

The Oliver Ranch, established 1880 in the Canyon City area.

Mountain Creek School, built 1910 in the vicinity of Mitchell.

Chess Wooden Homestead Cabin, ca. 1880, Mitchell vicinity.

"Mountain Ranch" House and Barn, built Ca. 1870s, 1880s, in the Mitchell area.

Howard-McGee House, built ca. 1890 in the Mitchell area

Lower Pine Creek School, built ca. 1900 in the Clarno area, now moved into the town of Fossil

Joaquin Miller Cabin, dating from 1865, now part of the Grant County Historic Museum complex at Canyon City

Henry H. Wheeler Landmark, erected in the 1920s in the Mitchell vicinity

Lovlett Corral, from ca. 1900, in the Umatilla National Forest in northeastern Grant County

Princess Cabin, Buck Bulch Cabin. Rapp Cabin, dating from 1902 — 1920s, all in Umatilla National Forest

Lyons Ranch, dating from the 1920s, Malheur National Forest in southeastern Grant County

Kight Cabin, Snow Cabin, Still Cabin, Blue Bird Cabin, and Brown Bear Cabin, dating from 1900 — 1926, all in the Malheur National Forest

Area tourism literature listings for places associated with early settlement, in addition to places identified above, include:

Old Red Barn, built 1883, on U.S. Hwy. 26 outside Mt. Vernon

Julia Henderson Pioneer Park, site of the annual Eastern Oregon Pioneer Picnic (dating from 1899), on SR 19 between Fossil and Service Creek

The Cant Ranch remains the most intact example of homestead settlement followed by sustained sheep and cattle ranching, inside the boundaries of the Monument. The National Park Service purchased 878 acres of the ranch in 1975 to expand the Sheep Rock Unit (Cant and Cant 1984; Steber 1984). Recognizing the significance of the property to the Monument's cultural history, the Park Service nominated the 200-acre Cant Ranch Historic District to the National Register in 1983 (Toothman 1983). The district has since been more broadly assessed as a cultural landscape, and encompasses twenty-four contributing resources — eleven buildings, five structures, and eight sites, including agricultural fields along the river (Taylor and Gilbert 1996). Now serving as headquarters for the John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, the Cant Ranch is also the focal point of the Monument's cultural resource interpretive program.

BLM records indicate that a handful of other homesteaders settled, if only temporarily, within the present-day boundaries of Sheep Rock, Painted Hills, and Clarno. Yet no evidence has arisen to suggest that any other significant homesteads survive on National Park Service-owned lands within the Monument. Probable locations for settlement along the river and streams are well-known and well-traveled. Park Service staff interviewed early in this project knew of no other standing homestead-era structures on Monument land (Hammett, Cahill, Fremd 1996). Burtchard, Cheung, and Gleason's archaeological reconnaissance of 1993 located nothing of significance in terms of homestead remnants. An identified historic enclosure in Sheep Rock turned out to be a part of the Cant Ranch. Sheepherder Springs Site, which includes a cabin, was identified in the survey on private land north of the Clarno (Burtchard, Cheung and Gleason 1998).

No comprehensive field survey of extant historic resources has ever been conducted in Grant or Wheeler counties. And yet, secondary sources are replete with names of early pioneers who settled in the nooks and crannies of the John Day country. There are likely to be extant historic properties associated with settlement in the larger area around the Monument, and there are undoubtedly historic archaeological sites and scatters to mark the locations of failed homesteads.

Some ranchers succeeded and remained on the land, reusing, adapting, moving, and remodeling early homestead structures over the years. Such 'evolutionary" ranches may not have the obvious integrity of the Cant Ranch, but will reflect layers of continued use over time. An example is the Mascall Ranch, at the head of Picture Gorge in Sheep Rock, where successive generations of the Mascall family have raised sheep and cattle since 1874 (Mascall 1939). Another is Burnt Ranch, five miles north of the Painted Hills at the mouth of Bridge Creek, homestead of James N. Clark, stage stop on The Dalles Military Road, and site of a well-known raid by Paiute Indians in 1865 (Fussner 1975: 23-24).

Other property types in addition to homesteads reflect the era of early settlement. The site of Camp Watson relates to government efforts to wrest the land from native inhabitants, opening the door to settlement. Situated near the former village of Antone on an old, unimproved stretch of The Dalles Military Road southeast of Mitchell, its precise location on the ground has been lost in recent decades. In 1932, local American Legion posts sponsored a dedication and placements of marble grave markers at the camp cemetery. In 1957, historian Judith Keyes Kenney easily located the site:

Today, the site of Camp Watson, about five miles west of Anatone [sic], is easily accessible from the Mitchell-John Day highway. Fort Creek still flows, though nothing else remains to be seen but marble markers in the cemetery, overgrown with pine. It lays on the western hill, with the markers placed in a row.. (Kenney 1957: 15-16).

In November of 1958, the National Park Service entered the site of Camp Watson on the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, under the theme of Westward Migration (Military and Indian Affairs). At that time, the field surveyor was unsuccessful in re-locating the site (Everhart 1958).

Family cemeteries such as the Clarno and Carroll family plots are mentioned in secondary literature. There are likely to be more of these on remote knolls and hillsides. This is affirmed by entries in the Oregon Cemetery Survey (conducted 1978) for fifteen pioneer cemeteries in Wheeler County and thirty-five cemeteries in Grant County (OR DOT 1978). Other rural crossroads structures associated with early settlement, such as the grange hall at Clarno, have yet to be inventoried by the State of Oregon or by the respective counties.

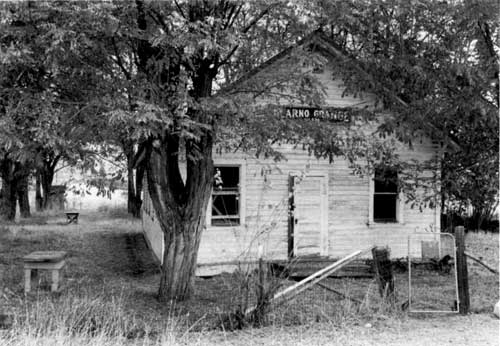

Fig. 21. The Clarno Grange, adjacent to

the SR 218 bridge at Clarno. F.K. Lentz, 1996 (National Park

Service)

Several suggestions are made for further investigation of cultural resources associated with the context of Settlement:

Conduct a historic resource survey/inventory of ranch inholdings within the Monument. Not specified within the scope of this historic resource study, a comprehensive, property by property field survey of inholdings would provide a stronger comparative basis for the interpretation of the Cant Ranch. Permission to access private lands, and the cooperation of private owners would be required. Such a survey could yield information about "evolutionary" ranches in the era, where the continued use and adaptation of the ranch complex to the present time has made historic character less visible.

Expand the excellent oral history program conducted in the Sheep Rock Unit to the Painted Hills and Clarno units.