|

John Day Fossil Beds

Rocks & Hard Places: Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Five:

TRANSPORTATION

For Euro-Americans, the upper John Day watershed remained an inaccessible pocket of north-central Oregon through the decade of the 1850s. Its rough terrain and unnavigable stream left it off the beaten track of early explorers, missionaries, and military men. Visitation by non-natives was almost non-existent until the early 1860s when gold was discovered in the vicinity of Canyon Creek on the upper John Day, at the present site of Canyon City. What first took shape as a well-traveled supply route from The Dalles to the mines at Canyon City was formalized as The Dalles-Boise Military Road by the late 1860s. For roughly fifty years, this wagon road provided primary access into the upper John Day country. Although nearby railroad stub lines did shorten the region's connections to markets after the turn of the nineteenth century, no major lines ever penetrated the upper basin. Easy access to the area now surrounding John Day Fossil Beds National Monument did not become a reality until the advent of the automobile, and the construction of state-supported roads and bridges in the 1910s and 1920s.

Oregon Trail Crossing

In the 1840s and 1850s, Willamette Valley-bound emigrants on the Oregon Trail encountered the John Day River in their route across the Columbia Plateau, between the Blue Mountains and the eastern entrance of the Columbia Gorge. Because of the dangers of travel in canoes and bateaux on the Columbia and the rugged basalt flows along its shores, the emigrants dropped south to follow a sandy, almost desolate trace through bunchgrass and sagebrush. Their route lay some seventeen miles south of the Columbia and brought thousands to a well-traveled ford on the John Day River, later known as McDonald's Ford/Ferry. The crossing provided little challenge. At mile 1,770 west of independence, Missouri, the emigrants were experienced in crossing streams. The John Day was relatively shallow but rocky, especially in August and September when the majority arrived at the ford. Some took advantage of the region to send their worn and hungry livestock to graze on the bunchgrass of the Plateau. This type of grass was far more abundant in the 1840s and 1850s than in subsequent decades when cattle raising and tilling dramatically diminished its presence and gave rise to a spread of sagebrush. Emigrant comments about crossing the John Day River are numerous but often terse:

- Jacob Hammer, 1844

[October] 17th We traveled ten miles and camped on John Day's river (Hammer 1990: 165).

- Edward Evans Parrish, 1844

Tuesday, Nov. 12. Came to a long, steep hill, doubled teams, got up and drove on two and a half miles to John Day's River and camped (Parrish 1888: 118).

- Joel Palmer, 1845

September 26. This day we traveled three miles. The road ascends the bluff; is very difficult in ascent from the steepness, requiring twice the force to impel the wagons usually employed; after affecting the ascent, the sinuosity of the road led us among the rocks to the bluff on John Day's river; here we had another obstacle to surmount, that of going down a hill very precipitous in its descent, but we accomplished this without loss or injury to our teams. This stream comes tumbling through kanyons and rolling over rocks at a violent rate (Palmer 1847: 60).

- Loren B. Hastings, 1847

October 16. Saturday. This day moved down to creek to John Days river (saw some Indians here). We crossed the river, found 26 wagons, camped; we passed and ascended a rocky ravine; we found three wagons that had been robbed by the Indians and 12 head of oxen driven off. Tears stood in the eyes of the women and children and the men were down in the mouth (Hastings 1926: 23).

- Elizabeth Dixon Smith, 1847

Oct 21 made 12 miles camped on John Days river scarce feed willows to burn here we put a guard for fear of indians which we have not done for 3 months before (Smith 1983: 138-139).

- Riley Root, 1848

[August] 28th 7 miles to crossing of John Day's river. Way down Beaver fork, very rocky, and road crosses it 4 times.

[August] 29th Down John Day's river, half a mile. Then ascended the bluff, about one mile, up a narrow, winding, rocky ravine, the worst we have travel[e]d. On the top of this bluff, the road divides, one leading to the Columbia river. The other, to the left, is the one we took (Root 1955: 29-30).

- William Wright Anderson, 1848

August the 28th we traveled 8 miles we pursued a verry narrow rough and rocky canyon for 7 miles where it empties into John days river we crossed this river and traveled one mile down it and camped here the road turns to the left and goes up a steep hill in a narrow canyon at the mouth of this canyon we were camped (Anderson 1848: 42-43).

- Honore-Timothee Lempfrit, 1848

19th September. As we were unable to find water anywhere we made preparations for travelling throughout the night. During the day I was able to help a poor woman who thought she was going to die. I delivered her baby. We left later on, about 2 o'clock in the afternoon, and traveled all night without the slightest mishap.

About midnight we went through a little valley where the cold was intense. At 5 o'clock in the morning we reached a creek. We took advantage of this by getting our horses to drink a little water but as there was no fodder we carried on for another seven miles and camped on the banks of the John Day River (Lempfrit 1984:144-145).

- Harriet Talcott Buckingham, 1851

[August 13] Traveled 12 miles over verry hilly road, ascended a mountain which we had to double team, and could hardly get up at that, Camp to night on John Days river a pleasant stream, upon the mountain just before we crossed the river we saw Mt. Hood towering high above the Cascades, A beautiful snow capt Mt (Buckingham 1984: 93-94).

- John S. Zieber, 1851

Tuesday, September 30 — We made an early start and had not proceeded over 1 1/2 miles when we passed those who had yesterday gone ahead. In 8 1/2 miles we came to a spring, affording water for cooking but not enough to water many cattle, and we were obliged to drive on to John Day River before we could get water for the afternoon. Camped after crossing the river. The valley of the river is narrow and without timber. A few small willows afforded scanty supply of fuel and we shall have to travel 36 miles before we get to wood. Fish appear to be plenty in the river (Zieber 1921: 332).

- Esther Belle (McMillan) Hanna, 1852

September 1st, Wednesday: Travelled about 12 or 14 miles today until noon over a good road, which brought us to John Day River. We had a very steep hill to descend in coming to it. We had all rejoiced to see water once more as our poor beasts had had none since yesterday noon. We have encamped on the river bottom, which is large and very level (Allen 1946:100).

- E. W. Conyers, 1852

September 9. We ascended a very long hill about two miles to the table lands, and traveled on three miles further and descended a very steep hill. Here we forded John Day River and traveled down the river one-half mile and camped. There has been good grass in this valley, but the ground is now barren, the grass having been eaten off. We drove our cattle to the table lands back of our camp, where we found bunch grass. Wood tonight is very scarce . . . " (Conyers 1906: 498).

These diary entries confirm that the early overland emigrants gave the John Day River little attention. Their goal upon reaching it was to find water for cooking and for their thirsty livestock. They forded it, camped on its banks, and took their livestock to graze on the bunchgrass on the tablelands above. None turned up the river to explore its course. The John Day was just one more stream to cross during a long journey to a destination west of the Cascade Mountains.

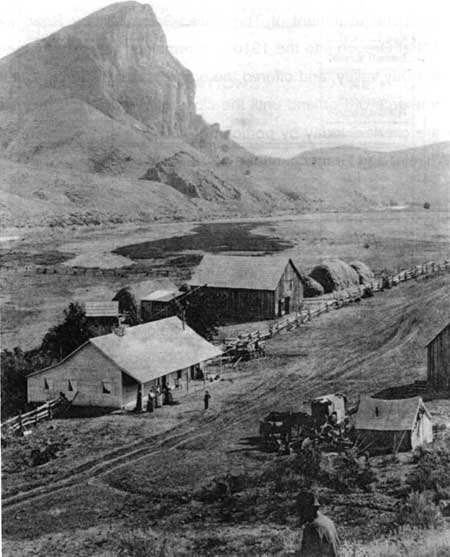

Fig. 22. Descent of western flank of the

Blue Mountains, Oregon Trail, 1849 (Cross 1850) (OrHi 35,

575).

The established crossing would change in time, reflecting a growing pattern of settlement east of the Cascades. In 1858, newcomer Tom Scott put in a ferry about a half-mile north of the emigrant ford. In October, 1864, Elizabeth Lee Porter forded the shallow stream and wrote: "Came over a nice road to Mud Springs. A nice day. A ranch house here just put up. 30 miles to The Dalles (Porter 1990: 32). In 1866 Dan Leonard is said to have built a bridge at the site. Leonard's Bridge reportedly collapsed in 1896 with a rancher from Condon and his heavily loaded wagon teams on it. Around 1904, W.G. "Billy" McDonald and his wife Mattie began operation of a ferry service at the crossing. It remained operational until 1922 when the Columbia River Highway opened (Gilliam County Historical Society, n.d.).

Supplies to the Gold Mines

The first improvements in transportation into the remote John Day country were triggered by the discovery of gold. Gold strikes on Canyon Creek in 1862 opened the gates to settlement of the valley. In the early 1860s, prospectors had made a series of important discoveries in eastern Oregon and far-flung Washington Territory (which then included Idaho). These included the placer deposits at Orofino, Pierce City, and Florence in north-central Idaho, as well as mines in the Boise Basin. In northeastern Oregon, miners found gold along streams in the Blue Mountains at Auburn and Sumpter. Miners also struck placer gold on the western flanks of the Blue Mountains in the upper John Day watershed in 1861 (Nedry 1952: 237-243).

In June, 1862, miners from Yreka, California, were traveling through central and eastern Oregon toward the new diggings at Florence, Idaho, on the Salmon River. When the party reached Auburn and the mines of the Powder River, the men learned that others had filed on most of the claims at Florence. William C. Aldred, a member of the group, then turned back to prospect Canyon Creek in the upper John Day region. He persuaded eighteen others to join him. When they returned to the place where they had camped but a few days before, they found several miners busily exploiting the placers. Aldred's group thus took claims at what they called Prairie Diggings four miles upriver and reportedly each soon secured a return of $10,000 for his efforts. Word spread like wildfire. Miners continued to pour in, swelling the population of the region almost overnight to more than five thousand (Oliver 1961:17-20).

In a matter of weeks, newcomers rushed to claims they staked along the banks of Canyon Creek. Others spied out deposits along the North Fork of the John Day and still others tunneled into the gravels in the valley near John Day to find rich but difficult-to-reach scatters of dust and nuggets along the bedrock. They lacked a technology to help them get to these riches, but, for the moment, the rush to the easy claims was sufficient to lead to the laying out of towns.

Mining communities arose at Independence on Granite Creek; Susanville on Elk Creek; Marysville on Little Pine Creek; Dixie Creek, a mining site a dozen miles east of Prairie City; Canyon City on Canyon Creek; and John Day, or Lower Town. Canyon City was the focal point of this activity — by September of 1862 some 500 to 600 miners had reportedly converged in the narrow gulch (Nedry 1952: 243). As a result of such rapid population increase in the John Day valley, the Oregon legislature carved Grant County out of Wasco County on October 14, 1864, less than two years after the gold strikes. The new administrative region sprawled south toward Nevada and included present-day Harney as well as Wheeler counties, both later cut out of Grant (Corning 1956: 102).

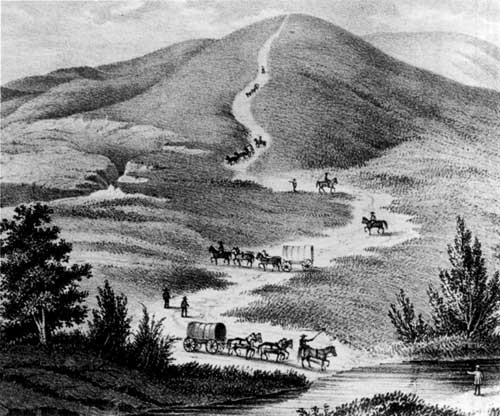

Fig. 23. Gold-mining town of Canyon

City, Oregon, modern day streetscape; F.K. Lentz, 1996 (National Park

Service).

Much-needed supplies to these communities moved by difficult trail southeast from The Dalles, the head of shipping on the Columbia River. Documentation for the existence of this particular trail prior to the gold rush decade of the 1860s is scant. The route was to some degree determined by existing ferries and bridge crossings over the Deschutes River. A ferry crossing at the mouth of the Deschutes had been in operation since 1853. Cattleman John Y. Todd built a bridge in 1860 (later know as Sherar's Bridge) at the strategic military crossing identified by Major Enock Steen along Wallen's 1859 route up the Deschutes. Another bridge, situated just four miles south of the river's confluence at the Columbia, was completed in 1862 by William Nix.

From these crossings, several trails traversed the high plateau in what is now Sherman County to the east, and dropped down into the deep valley of the John Day between Pine Creek and Bridge Creek. From there the trail followed Bridge Creek south past the Painted Hills to the vicinity of present-day Mitchell, then veered east over the hills into the valley of the upper John Day, and on to Canyon City. Quickly this general route saw heavy usage by those headed for the gold fields, and became commonly known as The Dalles to Canyon City Road (Neilsen 1985: 36-37).

Fig. 24. General route of The Dalles to

Canyon City Road through the Bridge Creek drainage, northwest of Painted

Hills Unit; F.K. Lentz, 1996 (National Park Service).

By April of 1863, 150 miners left The Dalles each day headed for the diggings at Canyon City, along with 200 pack animals, and ten to twelve freight wagons loaded down with payloads of 3,000 to 5,000 pounds apiece. The business of packing boomed between 1862 to 1885. Long strings of twenty to forty mules carried all the provisions necessary to sustain the burgeoning new population of the mining districts. These packers hauled picks, shovels, clothing, food, nails, rope, bolts, and dynamite. J.J. Cozart and Joseph Sherar are two of the more colorful packers mentioned in the record (Oliver 1961: 84-85; Neilsen 1985: 36-37).

Fig. 25. An eight-horse team pulling a

steam boiler, stopped in front of the Fossil Hotel, ca 1900 (City of

Fossil Museum).

Other enterprising men were quick to take advantage of the volume of passenger traffic headed to the mining interior. The Canyon City Stage Line began in the early 1860s, running three stages a week over the 180-mile road. Henry Wheeler, for whom Wheeler County is named, secured the mail contract in 1864 and was hired by Wells Fargo to carry out shipments of gold. Wheeler operated a four-horse stage between Canyon City and The Dalles for four years, risking life and limb in repeated confrontations with highwaymen and Indians. Stage stops became established along the route at Sherar's Bridge, Bakeoven, Cross Hollows or Shaniko, Antelope, Burnt Ranch, Bridge Creek, Antone, and Dayville, among others. Here, horses were changed, or fed and watered, and travelers could lay over to recover from the rigors of the trip. Most early stage stops consisted of a barn, corrals, and a farmhouse, where hearty, home-cooked meals were offered (Oliver 1961: 22-23, 86-87).

As The Dalles to Canyon City Road improved, pack outfits were replaced with commercial freight wagons capable of hauling larger items such as machinery, fencing, pianos, bricks, pipes, and handcarts. Freight teams consisted of from six to twelve horses, and two to four wagons. Freighting outfits continued to supply the John Day region, its ranches and towns, well into the twentieth century (Oliver 1961: 87-89).

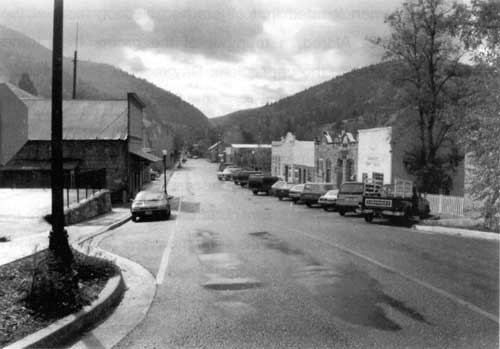

Fig. 26. Site of the ca. 1900 ferry

crossing at Spray; F. K. Lentz 1996 (National Park Service).

As the John Day country opened up to settlement, cattlemen and farmers filtered into the river valley. Their presence along the bottomlands led to locally-strategic river crossings. The shallow stream of the John Day could be readily forded eight months of the year. During times of normal high water in the late winter and early spring, cable ferries were operated by settlers at key locations, including the small settlements at Clarno, Twickenham, Service Creek, Spray, Kimberly, and Dayville. These ferries served as connecting links on stage and mail routes established in the 1870s and 1880s. With the advent of motorized transport after 1900, bridges were built at many of the old ferry crossings (Campbell 1976: 41-44).

Although navigable only by canoe and raft, the John Day River witnessed a brief period of colorful "steamboat" travel. The John Day Queen I was a miniature flat-bottomed sternwheeler built in 1892 by Charlie Clarno, son of pioneer Andrew Clarno of Wheeler County. Used as a pleasure craft and substitute ferry, the fifty-foot vessel operated during high water along a ten-mile stretch of the river above Clarno Rapids. In a flood of 1899, the well-loved little boat was lost, later to be rebuilt by Charlie Clarno in 1905 as the John Day Queen II (Campbell 1976: 52-61).

The Dalles-Boise Military Road

At about the same time that prospectors struck gold on Canyon Creek in central Oregon, the U.S. Congress, under the control of the Republican Party, was entertaining proposals to stimulate private enterprise in the American West. Unlike earlier programs where the Topographical Engineers of the U.S. Army surveyed and contracted for the construction of wagon roads west of the Cascades in the 1850s, the Republicans embraced a new model. They granted millions of acres of the public domain to private companies as an inducement to borrow money, hire surveyors, lay out, construct, and operate railroads and wagon roads across the West. Through an unparalleled "give away" of the nation's lands, Congress encouraged the private sector to create a transportation infrastructure which would meet the needs of miners, settlers, and townsite developers (Jackson 1952).

Oregon, which became a state in 1859, was the target of a series of land grant wagon roads. Ostensibly these were intended to stimulate private building of roads which could be used for military purposes. They were thus identified as "military wagon roads" and were laid out, at least, with terminal points to give credence to that designation. The Oregon routes included the following, in order of their establishment:

Oregon Central Military Wagon Road (Springfield to Fort Boise, Idaho), July 2, 1865 (13 Stat. 355).

Corvallis-Yaquina Bay Military Wagon Road (Corvallis to Yaquina City), July 4, 1866.

Willamette Valley and Cascade Mountain Military Wagon Road (Albany to Fort Boise, Idaho), July 5,1866 (14 Stat. 89).

The Dalles-Boise Military Road, February 25, 1867 (14 Stat. 409).

Coos Bay Military Wagon Road (Roseburg to Coos Bay), March 3,1869 (15 Stat. 340) (Beckham 1997: 2).

In each instance eager men of business and daring, which often far exceeded their capital and experience in locating and constructing wagon roads, formed companies and harangued the Oregon legislature to get the right to build the route and qualify for the land grant. Under the terms of the program, Congress passed the land grants to the state. When a section of the road was completed, the company could petition the governor to certify to its worthiness as a route of travel. With the governor's approval, the acreage was then transferred to the company which was free to sell or lease the tracts. The enabling legislation provided for three sections, each odd-numbered, for every mile of road built.

Lands of rich potentials were involved in these grants. In order to assure that would be the case, the road surveyors laid out routes which, wherever possible, passed through major stream courses and lush lake bottomlands. The Oregon Central Military Wagon Road, for example, when it reached the summit of the Cascade Range, did not head due east toward Boise. Instead, its surveyors turned it south into the Klamath Basin to carve out a huge section of the Klamath Indian Reservation as potential grant land. It then meandered into the valley of Goose Lake and into the Warner Valley and the Harney Basin, securing a bounty of lands eventually prized for their grazing.

So, in accord with what other companies were doing, the investors in The Dalles-Fort Boise Military Road examined a route into the John Day watershed to follow the stream east to the Blue Mountains. They found a trace well-established by mule teams and Wheeler's wagons, the existing Dalles to Canyon City Road. A regional history subsequently commented:

This route entered the territory now embraced by Wheeler county near where Burnt Ranch post-office now stands and followed the John Day river to Bridge creek, thence up Bridge creek to where Mitchell now stands, thence up the east branch of Bridge creek to the north branch of Badger creek, thence down Badger creek to where Caleb now stands and thence east along Mountain creek until it reached the border of what is now Grant county, about three miles west from the John Day river (Shaver et al. 1905: 636).

Under the terms of its grant of 1867, the company was to receive a bounty of public lands.

On October 20, 1868, the legislature approved the franchise of The Dalles Military Wagon Road Company to 'build" the route. The terms of the federal grant provided that as soon as the company had constructed ten contiguous miles, it would seek up to thirty sections of land (19,200 acres) and, selling its grant, could then finance further construction and, in turn, secure more land. On June 23, 1869, Governor George L. Woods stated he had "made a careful examination of said road" and commenced the certification process. There followed a second certification on January 12, 1870, attesting to completion of the entire road.

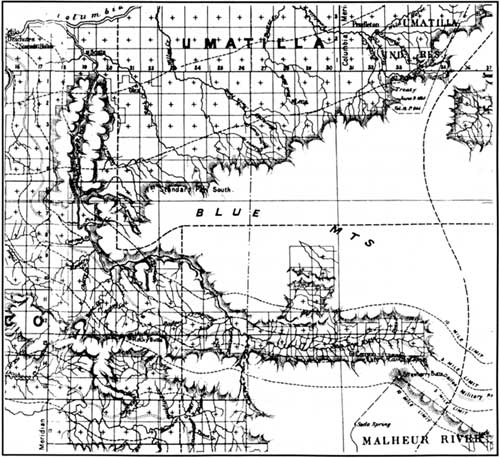

Fig. 27. Land grant corridor of The

Dalles-Boise Military Road in John Day watershed (General Land Office

1876).

On June 18, 1874, Congress authorized transfer of lands to the State of Oregon and on December 18, 1874, the Commissioner of the General Land Office withdrew from public entry all odd-numbered sections within three miles of either side of the road. The road company then selected its grant (or lieu lands if any of the odd-numbered sections had already passed into private ownership). The incorporators, mostly businessmen from The Dalles, then sold the grant for $125,000 to Edward Martin of San Francisco, California, on May 31, 1876 (Shaver et al. 1906: 439-440).

In the stroke of a single transaction, Edward Martin became one of the largest landowners in the Pacific Northwest. Born in Ennescorthy, Ireland, in 1819, Martin settled in California in 1848 and entered the real estate business. In 1859 Martin was an incorporator of the Hibernia Savings and Loan Society. By 1863 he also owned E. Martin & Company, a wholesale liquor business. At his death, Martin's Eastern Oregon Land Company held a reported 450,000 acres in Oregon (Bancroft 1890[7]: 184-185).

Public dissatisfaction with the military wagon roads mounted steadily. Unable to sell the acres patented to them and obligated to pay taxes on the grants, the wagon road companies were pushed toward bankruptcy. Having built, at best, only rudimentary traces through rugged terrain, the companies were sharply criticized by aggrieved travelers and shippers who confronted mud holes, washouts, fords rather than bridges, landslides, and interminable delays.

The Grant County Express in March, 1876, printed a scathing denunciation of the road:

There are places on the Dalles Military Road where the bottom has dropped out. If the Road Company should follow their road to where it ought to go they would find a warmer climate than Grant County. Like a great serpent it has dragged itself through the John Day valley, poisoning the whole country. The road is an illegitimate child of one ex-Governor Woods — after a carpetbagger in Utah. It was and is a great swindle (Mosgrove 1980: 49).

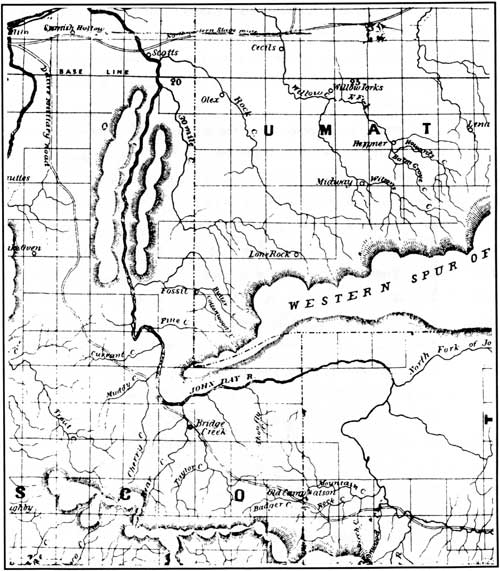

Fig. 28. Route of The Dalles-Boise

Military Road, 1878, through the John Day watershed (Habersham

1878).

Local settlers screamed unfair when the companies held out at "ransom prices" lush farmlands they desired to acquire. They charged, perhaps with justice, that the companies had obtained the land from the public but were not serving the public. When the companies erected gates and dared to charge tolls for using their rights-of-way, residents along the route were ready to mutiny. Some refused to pay; some drove around the gates; some tore them down and threatened to kill the toll keepers.

Public outcry grew steadily about the unfinished road through the John Day watershed and its lack of maintenance. In 1885 the Oregon legislature passed a memorial requesting Congress to look into possible fraud. On March 2, 1889, Congress authorized the Attorney-General to sue for foreclosure on all lands granted to The Dalles-Boise Military Wagon Road Company and to cancel all patents issued by the United States. Louis L. McArthur represented the United States; James K. Kelley and the law firm of Dolph, Bellinger, Mallory and Simpson represented the defendants. The lawyers argued the case in 1890. Judge Sawyer ruled for the defendants and dismissed the case. In 1891-92 the matter worked its way through the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals and to the Supreme Court. On March 6,1893, the highest court affirmed the validity of the land grant as sustained in the district court and court of appeals. The defendants had stressed throughout that the only proof of construction was the certificate of the governor. Once that had been issued the title to the land was absolute. To the dismay of thousands of disgruntled residents of Eastern Oregon, the courts agreed (Shaver et al. 1906: 440-441).

An early history of Sherman County confirmed the intensity of feeling about The Dalles-Boise Military Road:

The government was in full possession of all facts necessary to lay bare this scandalous conspiracy and convict the conspirators. There was a voluminous oral and written testimony in the shape of affidavits and written testimony of such an action. But the federal supreme court virtually said that two wrongs would make a right; that because congress had passed an unwise and ill-digested act, which imprudence was taken advantage of by an unscrupulous executive, the honest, homeseeking pioneers must suffer the penalty of combined pernicious legislation and executive truculency (Shaver et al. 1906: 441).

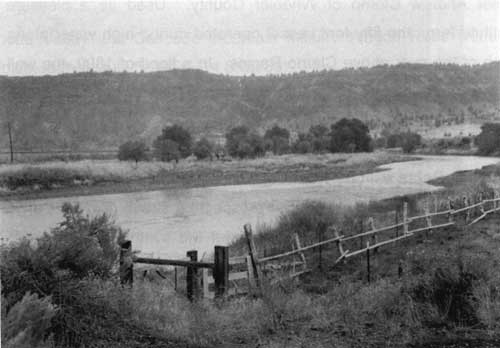

Fig. 29. Burnt Ranch, ca. 1890, stage stop on The Dalles-Boise Military Road, on the southern bank of the John Day River. (OrHi 4626-a).

The total grant secured by the Eastern Oregon Land Company was approximately 562,000 acres. Wailer S. Martin, President of the company in 1904, offered to sell quarter section lots in Sherman County to the federal government in units of not less than 10,000 acres at the rate of $60 per acre. Martin claimed that the company had made extensive improvements, including fencing, and the price was therefore justifiable (Shaver et al. 1906: 442).

The general alignment of The Dalles-Boise Military Road persisted on maps of central Oregon into the 1910s. It remained the primary overland route into the John Day valley, and offered the quickest access to the Columbia Basin and the commerce of Portland until the close of World War One. Remnants of the route are overlaid today by portions of U.S. 26, and segments of graveled roads in Wheeler and Grant counties.

The Advent of Railroads

The advent of railroads in the Pacific Northwest had little direct effect upon settlers in the John Day country until after the turn of the nineteenth century. Although none of the major lines ever entered Grant or Wheeler counties, nearby railheads stimulated horse-drawn stage and freight connections throughout the region. The developing sheep industry particularly profited from the construction of feeder lines running south from the Oregon Railway & Navigation Company's primary railroad. Located along the south bank of the Columbia River, that railroad was completed in 1882 (Fussner 1975: 108; Elliott 1914:170).

First among the "stub lines," built in 1889, was a connection between Heppner Junction on the Columbia to Heppner, some forty-five miles to the south. Separated by a western spur of the Blue Mountains from the John Day basin, Heppner was especially difficult to access. Nonetheless, some stock from valley ranches was driven over the rough terrain to railhead (Fussner 1975: 108).

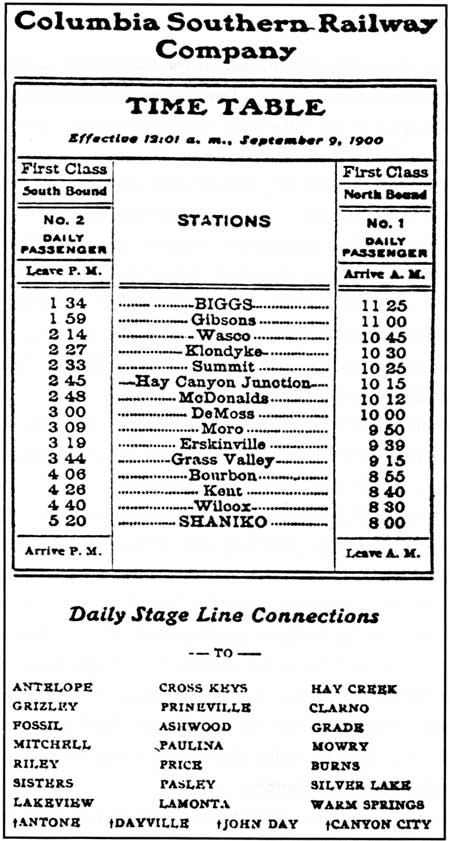

Of greater import to John Day settlers was the completion in 1900 of the Columbia Southern Railroad line, which ran for seventy miles from Biggs on the Columbia south to Shaniko on the high plateau. Developers planned for the line to extend all the way to Prineville, but the plans failed to achieve fruition.

Shaniko was strategically situated on The Dalles-Boise Military Road, and it boomed as the terminus of the line. The town briefly claimed distinction as the busiest wool shipping center in the world. Freighters from the John Day country hauled in wagons filled with heavy sacks of wool for export to scouring plants and mills. Connecting stages ran daily from Shaniko east to Mitchell, Dayville, and Canyon City. (Culp 1972: 100-102; Brogan 1977; 129).

Fig. 30. Columbia Southern Railway time

table — Biggs to Shaniclo — noting stage connections to towns

in the John Day valley (Culp 1972).

The Union Pacific (formerly the Oregon Railway & Navigation Co.) extended another feeder line south from Arlington on the Columbia River to Condon in Gilliam County in 1905. Its arrival prompted a small building boom. There was much excitement about the prospect of the railroad being continued south another twenty miles to Fossil, the county seat of Wheeler County, but this did not occur (Gilliam County Historical Society n.d.).

One of the most colorful railroad building episodes in central Oregon — one which ultimately spelled the demise of Shaniko as an important terminus — was the race up the Deschutes Gorge. W. F. Nelson, R. A. Ballinger, and L. I. Gregory on February 24,1906, incorporated a company which came to be known as the Oregon Trunk Railroad (Gaertner 1992: 97-121). Crews initiated surveys along the banks of the Deschutes River and began preliminary grading during the summer of 1906. The plan was to build a line from Wishram, Washington, across the Columbia River and up the Deschutes River to tap the vast pine forests of the eastern flank of the Cascades and the forests on the upper Crooked River and Ochoco Creek in central Oregon. Capital shortages curtailed construction after laying one and a half miles of track. In August, 1908, unable to meet the continuing financial burdens facing the Oregon Trunk, Nelson, the company president, sold out to V. D. Williamson.

A competing line, the Deschutes Railroad (a subsidiary of the Union Pacific), began grading its right-of-way up the river in July, 1909, when the Oregon Trunk resumed construction. On February 15, 1911, the Oregon Trunk track crew reached Madras with the Deschutes Railroad only six weeks out of the town. Finally, investors in both the lines — James J. Hill and E. H. Harriman — gave up the battle and merged their efforts at Madras. The Oregon Trunk reached Bend on September 30, 1911; the first passengers arrived on October 30 (Gaertner 1992: 97-121).

Settlers in the upper John Day basin were especially well-served a few years later by a more easily accessed railhead at Prairie City, thirteen miles east of the town of John Day in eastern Grant County. The Sumpter Valley Railroad, a narrow gauge line, was built from Baker City to Sumpter between 1890 and 1897, and completed west in 1909 to Prairie City. The little train was slow, but much appreciated by locals who dubbed it the "puddle jumper," "teakettle," and "stump dodger." The Sumpter Valley Railroad hauled cattle, logs, gold ore, sheep, passengers and supplies from Prairie City to the main line of the Union Pacific at Baker City until 1933 (Culp 1972: 91-94; Oliver 1961: 194-195).

In later decades, Wheeler County acquired its own small passenger line. Built in 1929 by the Kinzua Pine Mills Co., the Kinzua & Southern Railroad operated from Condon thirty miles south to the sawmill community of Kinzua. Passengers and mail were delivered via a Mack rail bus. (Culp 1972: 97).

Motorization

The advent of motorized transportation in the early twentieth century finally opened the John Day region to a larger world. At first, sparsely populated Grant and Wheeler counties lacked the tax base to effect any significant improvement of its network of horse-drawn freight and stage roads. The situation began to improve in 1913 when the Oregon State Legislature created the State Highway Commission and appropriated $1.7 million to assist in road construction statewide. In 1917, the legislature approved funds for work on two highways in the upper John Day basin, the John Day River Highway, and the Pendleton-John Day Highway (Corning 1956: 113; Mark 1996:29).

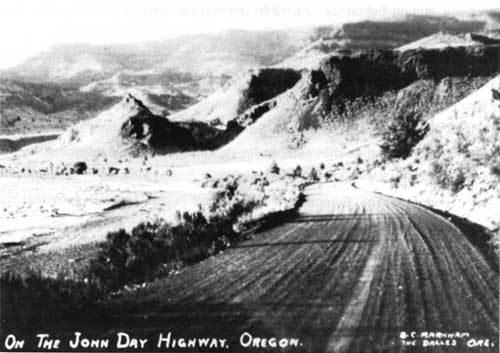

Fig. 31. Postcard depicting the John Day

Highway, graded and graveled, n.d. (City of Fossil Museum).

By 1914, an improved road was built from Biggs on the Columbia River via Condon into Fossil — the same year the first gasoline pump was installed at Fossil's General Mercantile. Over the next few years, with state funds, this road was continued south down Service Creek, along the north bank of the John Day River through Spray and Kimberly, south along the east bank (bridging over at the Humphrey Ranch), and into Butler Basin along the west bank past the Cant Ranch, now headquarters of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument. A narrow winding stretch of the road was reportedly pushed through Picture Gorge around 1917 (Fussner 1975: 131; Mark 1996; 29, 36).

Fig. 32. Picture Canyon, John Day, 1939

(OHS — CN 023724).

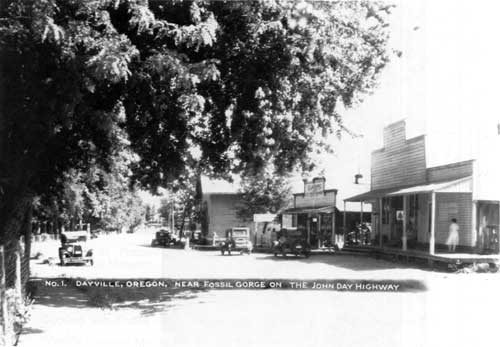

Fig. 33. "Dayville, Oregon, near Fossil

Gorge on the John Day Highway" (OrHi 15142).

This entire segment, from Kimberly to the Mascall Ranch just southeast of Picture Gorge, was clearly in place in 1925 when the U.S. Geological Survey mapped the topography of the Picture Gorge quadrangle. South and east of Picture Gorge, the new highway joined the route of the old Dalles-Boise Military Road, continuing east through Dayville and on to John Day, all the way east to the town of Ontario on the Idaho border.

The John Day Highway (now S.R. 19), laid open the long-secluded country north of Picture Gorge to travelers and tourists alike. The highway also directly linked the still-remote communities of the valley with Columbia River markets. The Oregon State Highway Commission was entirely aware of the commercial value and tourist potential of the new highway when it reported on its progress in the Sixth Biennial Report to the Governor:

The opening of the John Day Highway by completing the gap between Olix and Gwendolen, north of Condon, and surfacing between Spray and the North Fork, has made possible all-year travel into the John Day Valley, with resulting saving to the residents of that region in decreased hauling costs of wheat, wool, etc. The extension of the forest project from Prairie City through Austin to Unity, all of which has been graded and part surfaced, will be the means of opening this entire highway to through travel from Ontario, via the wonderful Picture Gorge and fossil beds, to Arlington, as an alternate route to the Old Oregon Trail (Oregon State Highway Commission 1923-1924: 10).

Oregon's Market Road Act of 1920 apportioned state and county taxes for local routes, allowing the construction of short new road segments and the upgrading of older ones throughout Grant and Wheeler counties. In 1921-22, workmen began limited improvements along the old military road from Antelope to Mitchell, affording travelers better access to the Painted Hills area along Bridge Creek. The north Wheeler County towns of Fossil and Clarno were linked in 1926 with a new market road, later to be designated as part of S.R. 218 (Mark 1996: 29-30).

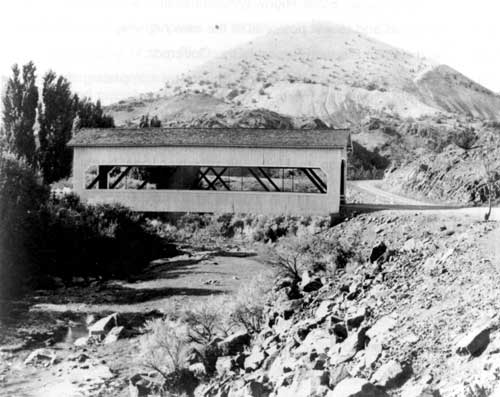

In the early 1920s, a road from Redmond via Prineville to Mitchell was renamed the Ochoco Highway. Four miles northwest of Mitchell, the road spanned Bridge Creek with a covered, ninety-foot Howe Truss bridge built in 1917. The picturesque bridge remained in place until the early 1950s (Stinchfield 1983: 10). The Ochoco Highway was designated as part of U.S. 28 (now U.S. 26) and was improved through the early 1930s.

Fig. 34. Covered bridge over Bridge

Creek on Ochoco Highway northwest of Mitchell, n.d (OrHi

100704).

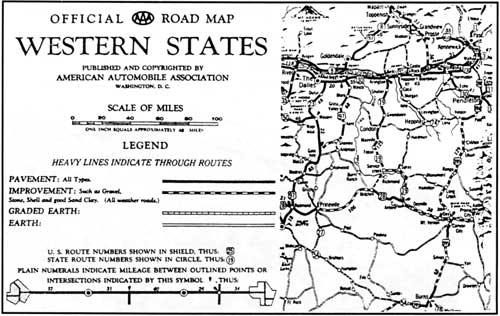

Rerouting of the Mitchell to Dayville segment of the Ochoco Highway — away from old military road alignment through Antone, and north to its present alignment above Picture Gorge — appears to have taken place between 1932 and 1936. The U.S. Geological Survey's 1932 topographic map of the Dayville quadrangle shows the "Mitchell Road" veering off to the west just southeast of the Mascall Ranch, in the approximate location of today's Grant Co. 40. In 1936, however, an American Automobile Association road map shows the new paved segment from Mitchell to Picture Gorge.

Fig. 35. Portion of Official AAA

Road Map of the Western States, 1936 (American Automobile

Association).

By 1936, most of today's existing state and county roads in the upper John Day basin were in place. With the exception of short paved segments between Mitchell and Picture Gorge, and between Fossil and Condon, roads mapped for motorized travel in Grant and Wheeler counties were "improved" with gravel or sand, and considered "all-weather" in quality. The historic trace from Antelope to Mitchell, along the once heavily traveled military route to Canyon City, soon declined in use and faded from memory.

Cultural Resources Summary

Transportation played a pivotal role in the development of the upper John Day basin and, from an early date, fostered two types of cultural resources which have left traces on the landscape today: transportation infrastructure; and commercial establishments that catered to the traveler.

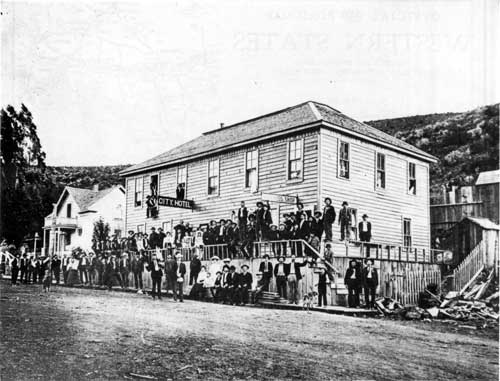

Fig. 36. "City Hotel and Harness Shop"

at Mitchell (City of Fossil Museum).

The 1860s gold rush to the Canyon Creek district triggered the overnight opening of a busy supply route from The Dalles to the mines along a largely unimproved dirt wagon road. Before the close of that decade, the route was surveyed, mapped, and partially improved, as The Dalles-Boise Military Road. It remained in heavy use for over fifty years. Remnant sections of both roads — sometimes divergent but more often overlaying one another — have been found in Wasco, Sherman, Wheeler and Grant counties (Nielsen et. al. 1985). All along this major route every fifteen to twenty miles arose stage stops, such as Burnt Ranch at the mouth of Bridge Creek, offering basic services to travelers. Settlement in small valleys tributary to the John Day in the 1870s and 1880s stimulated the construction of secondary mail and stage roads, cable ferries — such as that operated at Clarno — and rudimentary bridges. In 1905, nearly every tiny community in Wheeler County — including Mitchell, Fossil, Twickenham, Richmond, Waterman, and Caleb — boasted one if not two hotels (Shaver et al. 1905: 648-656).

Fig. 37. Sidewalk Café (c. 1945)

in Mitchell; F.K. Lentz 1996 (National Park Service).

Railroads left a more limited but enduring mark on the land in Grant and Wheeler counties; both the Kinzua and the Sumpter Valley Railroad operated for only a few decades (Culp 1972: 97; Oliver 1961: 193). Motorization ushered in the construction of multiple graded roads, paved highways and bridges. Motor car travel spawned roadside services offering gas, food, and lodging. Most services, such as the Sidewalk Café in Mitchell, hugged the highway at the center of small towns. Others, such as Scotty's Gas Station and Store at the junction of the John Day Highway and the Ochoco Highway, sprang up at rural crossroads.

A few surviving cultural resources associated with transportation in the Grant and Wheeler area are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. These include:

The Sumpter Valley Railway Passenger Station, built in 1910, now home to the Dewitt Museum in Prairie City.

The Sumpter Valley Railway Historic District, restored and operational, in the vicinity of Sumpter and Whitney in neighboring Baker County.

Oregon State Inventory of Historic Places listings from Grant and Wheeler County in the category of transportation include:

The Prairie City Hotel, 1910, in Prairie City.

The Kimberly Road Segment of the Spray-Long Creek Wagon Road, ca. 1890.

The Central Hotel, ca. 1880, in Mitchell.

Area tourism literature listings, in addition to places identified above, include:

The Shaniko Hotel, at Shaniko, the terminus of the Columbia Southern Railroad.

Stage Stop Site, ca. 1918, at Service Creek.

Ferry Crossing Site, ca. 1900, at Spray.

The Union Pacific Depot, built 1906, in Condon, now the Gilliam County Depot Museum.

The Oregon Trail John Day River Crossing at McDonald's Ford, east of Wasco in Sherman County.

The most significant transportation resource located within the Monument and in very close proximity to its boundaries is the alignment of The Dalles-Boise Military Road. From John Day, the road followed the general route of what is now U.S. 26 to Dayville, branching off to the west on what is now Grant Co. 40, past the Mascall Overlook, through the former village of Antone, continuing over the hills and dropping down into Mitchell. From Mitchell, the old road ran northwest down Bridge Creek along the general alignment of what is now Bridge Creek Road (Wheeler Co.), passing through the south-easternmost corner of the Painted Hills Unit, and continuing to the mouth of Bridge Creek at the John Day and on to Antelope. The location of the military road (and its antecedent The Dalles to Canyon City Road) was field inspected, but not mapped, by Neilsen, Newman, and McCart in 1985.

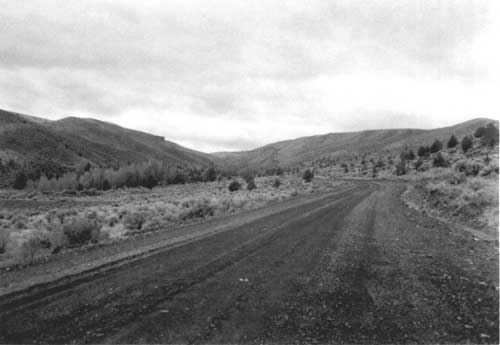

Fig. 38. Grant Co. 40, following the old

alignment of The Dalles-Boise Military Road — view to the west off

U.S. 26 near Picture Gorge; F.K. Lentz, 1996 (National Park

Service).

Key recommendations for further investigation of cultural resources associated with the context of Transportation are:

Further document the establishment, routing, construction, and maintenance of The Dalles-Boise Military Road. Models for such studies are those mounted for the Oregon Central Military Wagon Road (Beckham 1981) and the Coos Bay Wagon Road (1997).

In addition to a thorough literature search, undertake a field survey to ground-verify, photo-record, and map surviving remnants of the road. Such a study, if sponsored jointly with the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office and the Bureau of Land Management, has the potential to identify intact segments along the length of the route that may be eligible for National Register listing.

Intact segments in Grant and Wheeler counties in the vicinity of the Monument should be proposed for nomination to the National Register.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002