|

John Day Fossil Beds

Rocks & Hard Places: Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Six:

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The economy of the upper John Day basin is grounded in the rich natural resources of the region. Since the early 1860s, minerals, grasslands, meadowlands, and forests have provided the basis of human livelihood. The first wave of economic development to sweep the John Day country was gold mining. Ultimately, gold mining would have far-reaching effects on the landscape, altering the banks of rivers and streams, and ushering in early forms of agriculture and town-building. Cattle ranching and sheep ranching soon surpassed mining as an economic pursuit and a way of life. These occupations held sway through the first three decades of the twentieth century. After 1940, harvesting and processing the vast stands of timber in the private forests and national forests of Grant and Wheeler counties emerged as the mainstay of the local economy. In all of these industries, small operators and large commercial concerns alike had their hands.

Mining

The fevered rush of miners prospecting streams throughout the interior of the Pacific Northwest was initially driven by the gold strikes of 1858 in the Fraser River region in British Columbia. The riches were sufficiently attractive to draw miners from southern Oregon and California (Reinhart 1962: 108-135). In succeeding years, gold seekers repeatedly trespassed on Indian reservations and unceded lands throughout the Columbia Plateau in their search for the precious metal. R. H. Lansdale, Indian Agent at Fort Simcoe on the Yakima Reservation in Washington Territory, noted on August 15, 1860, the great numbers of white men passing through the region. "Many of these men," he wrote, "are miners from California, and I record with great pleasure, that, as far as has come to my knowledge, they have always respected the rights and feelings of the helpless Indians" (ARCIA 1860: 205).

Gold seekers repeatedly attempted to re-find the legendary "Blue Bucket Nuggets," a rich strike allegedly made in 1845 during the transit of overland emigrants following the hapless Stephen H. L. Meek. These travelers attempted to blaze a new emigrant route west from Fort Boise through central Oregon to the Cascades with the intent to enter the upper Willamette Valley. The route proved difficult, indeed deadly for some, and took them through the northern Harney Basin and across the High Desert toward the Deschutes River. Unable to find a pass in the Cascades, they descended the rugged banks of the Deschutes and rejoined the Oregon Trail at The Dalles. Serious attempts to relocate the mine continued for over a century after the initial discovery (Clark and Tiller 1966; Brogan 1977: 40-41).

Several accounts suggests that golden potentials lurked in the Blue and Strawberry mountains. Members of Capt. Wallen's military exploring party brought in reports of gold on the Malheur River. In the spring of 1861, J. L. Adams recounted in Portland that he had found gold in the "upper country." Adams then led an exploring party to the John Day River, found prospects, returned to Portland, and in the early fall of 1861 set out again for the North Fork of the John Day. W. S. Failing and E. Lewis, both members of the initial exploring group, set out in November with thirty-two men and fifty-six animals loaded with supplies for six months of residency. By January, 1862, they had erected cabins at Otter Bar, a site somewhere on the upper John Day River. Hostile encounters with Indians caused the men to flee in February to The Dalles, but they soon returned (Nedry 1952: 238-240).

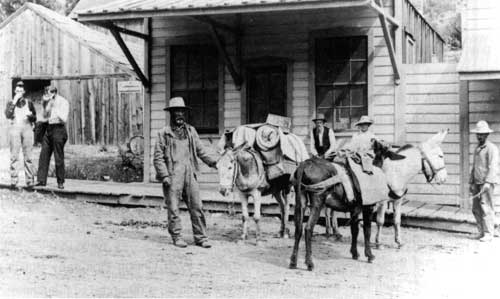

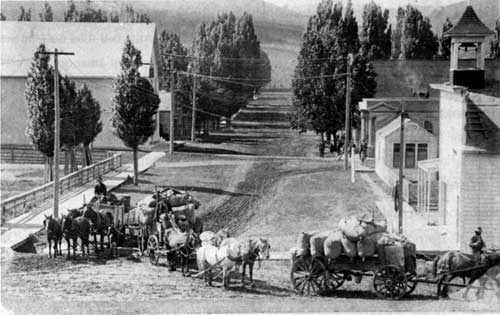

Fig. 39. Miners with pack mules on the

streets of Canyon City, ca. 1920 (OrHi 57533).

In June of 1862, a strike on Canyon Creek drew thousands to the John Day basin. The rush to Canyon City and other mountainous areas in what is now eastern Grant County triggered far-reaching change in the region — permanent settlement, the advent of ranching and agriculture, and the beginnings of large-scale resource extraction. Although the rush was over by 1870, the pursuit of gold remained an important factor in the economy of Grant County well into the twentieth century, often through well-capitalized industrial operations. One source has estimated that, by 1972, as much as $30,000,000 in gold had been mined from the gravel beds of Canyon Creek and the John Day River (Thayer 1972: 4).

In December, 1862, miners drafted the regulations of the John Day Mining District, a region extending up the river to its summit with the Malheur watershed and the ridge west of Canyon Creek. They set creek claims at seventy-five running feet on the stream from one high water mark to the other. Bank claims were fixed at seventy-five running feet on a stream back 300 feet from creek claims. Shaft claims were set at seventy-five feet on the front and extended to the center of the hill. Gulch claims were set at 150 running feet in the gulch and fifty feet to either side of the channel. Each miner was allowed two claims, but each had to be of a different type. Significantly, the racism of the miners surfaced in these initial agreements: "No Asiatic shall be allowed to mine in this district," read the ordinance (Oliver 1961: 21-22). Miners from other diggings who had encountered the hardy Chinese attempted to block their presence.

Chinese miners did, nonetheless, enter the area. Dozens lived at remote placer and lode mines. Two large concentrations of Chinese residents occurred at Canyon City and John Day. John Day's 'Chinatown' was a substantial settlement on the banks of Canyon Creek. Although the Chinese population had sharply declined by 1900, two notable figures remained their entire lives and became an integral part of the John Day community — the herbal doctor Ing Hay and his friend and business partner Lung On. The two men operated the Kam Wah Chung & Company store, which served as a doctor's office, trading post, pharmacy, social club, bank, assay office, and a shrine. Doc Hay was a legendary figure in central Oregon, and his herbal remedies were popular with Chinese and Euro-Americans alike. The Kam Wah Chung Company Building (built ca. 1867, with later additions) still survives today, a reminder of the Chinese experience in the gold mines of eastern Oregon (Hartwig 1973).

Fig. 40. Chinatown at John Day, 1909.

Kam Wah Chung & Co. Building to the left (OrHi 53764).

Miners brought considerable energy and new technology to central Oregon. Chief among their projects was construction of ditches and flumes to divert water to the diggings. Early in 1862 the claimants at Prairie Diggings formed a joint stock company to build a ditch for two miles. They completed it by early summer. Miners at Marysville and Canyon City built a ditch to divert large amounts of water from Indian and Big Pine creeks through twelve miles of hand-dug canal. This ditch, constructed in 1862, continued in operation into the early twentieth century. The early miners also felled trees, sawed lumber, constructed flumes, and, as demand dictated, built sawmills to help construct the towns where they settled (Anonymous 1902: 386-387).

Development of lode deposits, for a time, brought a new optimism about gold mining in the region, even as the excitement of the initial rush faded. During the summer of 1867, J. A. Porter & Company erected an eight-stamp, two-battery quartz mill with a capacity of crushing eight to ten tons of ore per day. Financed by $5,000 in sale of stock, the mill was promising but failed to turn a profit (Anonymous 1902: 393). Optimism still ran high some thirty years later, in a special issue on "The Gold Fields of Eastern Oregon," the Morning Democrat of Baker City described many active mines in Grant County in the Canyon, Green Horn, Red Boy, Granite Districts, and noted:

Quartz mines are being developed in the old placer districts that are simply astonishing in their richness. . . . At Quartzburg, near the town of Prairie City, are a number of gold bearing ledges, some of which have been worked by arrastras and stamp mills for several years with good results. . . . One prospect in particular, a mile and a half from town [Canyon City], gives much encouragement to its discover, Mr. Isaac Guker. . . Lately Mr. Guker has found nuggets or flat chunks of gold, varying in value from forty to over one-hundred dollars (Anonymous 1898: 25, 33).

Hydraulic mining was another method employed in Grant County. Water in a ditch at a higher elevation was sent down a hose through a narrowing nozzle. The high pressure stream was directed at a hill side or cut bank, washing tons of ore into a sluice where the gold was separated out. The Humboldt Mining Company, among others, ran a large hydraulic operation near Canyon City, using an eight and one-half mile ditch, and 2,600 feet of hydraulic pipe (Anonymous 1898: 35). Remnants of this ditch may still be discernable on the west side of Canyon Creek, just south of Canyon City.

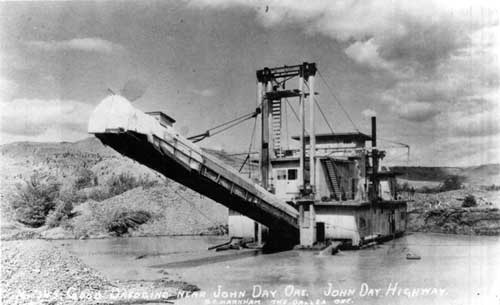

Fig. 41. Gold Dredging near John Day, OR

(OrHi 77491)

Dredging was a third method of mining employed along the John Day River in the early twentieth century A technique particularly destructive to bottomland meadows, dredging tore up former channels of the river, washing away soil, and spitting out acres of telltale mounds of gravel. The dredge would create and float on its own pond, using water diverted from a nearby stream. Dredging operations were established by the Empire Gold Dredging & Mining. Long-time rancher Herman Oliver summed up the impact of dredging on the landscape:

After a beautiful meadow had been dredged, it was turned into a worthless, unsightly, formless pile of rocks. The good soil washed away with the water. . . The meadows furnished the hay for winter feeding, so some ranchers, their meadowlands gone, no longer had a year-around business, and had to sell their grazing land or else go somewhere lese to get more hay land.... The dredge was usually owned by outsiders, and the profits went to San Francisco or someplace outside of Grant County. So the county lost all around (Oliver 1961: 29-30).

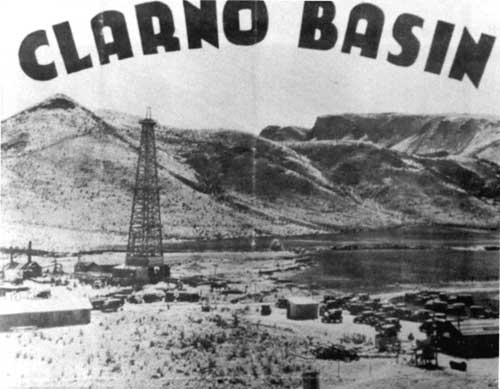

Although Wheeler County lacked the concentration of rich gold deposits of Grant County, the Clarno area witnessed brief excitement over oil. In 1927, the Clarno Basin Oil Company sunk one well on the Hilton Ranch at the mouth of Pine Creek. The company sold shares to hopeful investors at $10 a share, and spent an estimated $300,000, drilling to a depth of 4,800 feet. Promotional literature proclaimed, "One Good speculation is Worth a Lifetime of Saving!" and promised that the Clarno basin was proven to contain oil and gas. Eager visitors from all over the state congregated at the field on Sunday afternoons, in the hopes of seeing oil come gushing forth. In the end, the prospect yielded natural gas but no oil (McNeil 1953: 273; Fussner 1975: 29).

Fig. 42. Detail from promotional

literature for the Clarno Basin Development Company, ca 1927, F K Lentz

1996 (National Park Service).

Cattle Ranching

In the years 1862-1922, settlers steadily pushed into Grant and Wheeler counties. While the initial lure was gold, grasslands provided the more enduring attraction. The rugged upper John Day watershed possessed both fertile bottomlands along the river and its tributary streams as well as upland areas of abundant bluebunch wheatgrass. The nutritious grass proved an irresistible draw to raisers of cattle, horses, and sheep. As stockmen realized the potentials of the interior of the Pacific Northwest, they rushed in to secure lands and place their herds. J. Orin Oliphant, historian of the "Rise of Transcascadia," described a grazing province of some 16,000 square miles in central and eastern Oregon. "Here, on uplands and lowlands, on grasslands and sagelands," wrote Oliphant, "cattle in large numbers roamed freely the year round in scattered districts of a cattlemen's kingdom which flourished during the 1870's and much of the 1880's" (Oliphant 1968: 75-76).

Initially, cattle to feed hungry miners were brought from west of the Cascade Mountains. In 1862 alone, 46,000 head were imported from west of the mountains, as compared to an estimated 7,000 head of cattle entering the region with overland emigrants from the east. This build up of herds was in direct response to the local mining market, the seemingly inexhaustible grasslands, and the opportunity to use the Homestead Act (1862) or the cash entry purchase system secure to key range lands and water sources (Oliphant 1968: 79).

Early cattle ranchers in Grant and Wheeler counties took advantage of the luxurious, stirrup-high bunch grasses. Their rangy herds grazed uncontrolled throughout the year on the vast, unfenced ranges of the public domain, on rocky hillsides and in mountain forests. Large cattle holdings in Wheeler County in the early years included those of the Gilman & French Company with 38,120 acres; the Sophiana Ranch with 10,095 acres; and the Butte Creek Land, Livestock & Lumber Company with 8,634 acres. The Gilman & French holdings included Henry Wheeler's homestead, the Corn Cob Ranch, six miles north and west of Spray. From 1872 through 1902, the Gilman brothers and the French brothers also acquired the Prairie Ranch, the Hoyt Ranch, the Sutton Ranch, the O.K. Ranch, and various Wheeler County parcels needed to control most of the land in between. All of these places were well capitalized and famous for their large barns, extensive fences, early indoor plumbing and electrical systems, and productive hay and grain fields (Shaver et al. 1905: 657; Stinchfield 1983: 28-30).

In Grant County in 1885, vast cattle ranches included Todhunter & Devine's White Horse Ranch with 40,000 cattle, and French & Glenn's "P" Ranch, with 30,000 cattle. The Bear Valley, Silvies Valley, Juniper, Crane Creek, Otis, Murderer's Creek, and Paulina valleys were all monopolized by cattlemen.

This stranglehold over some of the best meadowlands and water sources was decried by the region's champions of economic development. The periodical West Shore proclaimed in 1885:

When . . .these numerous valleys are wrested from the grip of the cattle kings and divided up into homesteads for actual settlers; when they are made to yield the diversified products of which they are capable; when the numerous farmers shall utilize the adjacent hills for the grazing of as many cattle, sheep, etc. as each can properly care for; then the school house shall replace the cowboy's nut and the settler's cabin shall be seen in every nook and corner of these vacant valleys, then the country will multiply its population and wealth, and the era of its real prosperity will dawn (Anonymous 1902: 399).

In the early 1880s, many of the larger cattle operations in northern and central Oregon did in fact begin moving or selling their herds into the Harney Basin to the south. There they discovered the lush, wide-open meadows of that watershed, and began to push for the closure of the Malheur Indian Reservation. In Grant and Wheeler counties, sheep raising gained a firm foothold in the local economy, in the same decade (Anonymous 1902: 394).

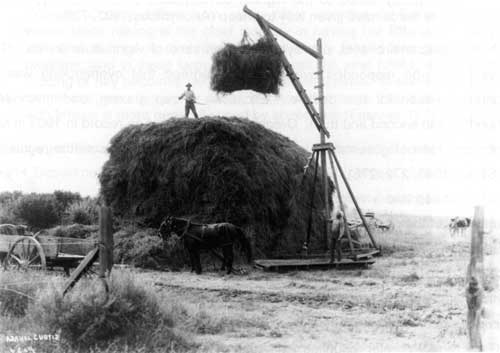

By 1890, after a five-year drop in cattle prices from a peak in 1885, and an especially severe winter in which ranchers suffered heavy losses, cattlemen began gradually to consider the advisability of providing their herds with winter feed (Strong 1940: 262). Alfalfa hay and grains to supplement winter feed could be successfully grown on irrigated bottomlands of the John Day and its tributary creeks. The harvested fields made excellent fall pasture for the herds. This combination of livestock raising and limited agriculture created a healthy economic mix that persisted in both Grant and Wheeler counties into the twentieth century (Fussner 1975: 86).

Fig. 43. Hay stacking in eastern Oregon

(Photograph by Asahel Curtis) (OrHi 54200).

Several factors, nonetheless, worked to further erode the survival of the cattle industry in Grant and Wheeler counties in the later years of the nineteenth century and early decades of the twentieth. Overgrazing of the range, the competition of the sheep industry, and homesteading were its chief challenges. As these challenges were met, the open range cattle business was transformed into the modern fenced range industry that persists today (Strong 1940: 258)

As early as the 1880s, the range was beginning to show signs of lower production due to overgrazing. Grant County recognized the effect this was having on its cattle industry in 1902:

Stock raising has been in the past and must continue to be a leading pursuit. At one time the stockman's investments were almost entirely in cattle, but in recent years the range has not furnished grass in quantity and quality suited to the highest development of this industry, and the cattle herds have given way to sheep (Anonymous 1902: 728).

In a questionnaire sent out by the Department of Agriculture in ca. 1905, cattlemen who responded overwhelmingly agreed that overstocking was the primary reason for this decline. Excessive sheep grazing, and methods of handling ran second and third. Oregon cattlemen went on record in 1903 in favor of some form of government control of the range under reasonable regulations (Strong 1940: 272, 276).

Sheep had a notably more destructive effect on range grass than cattle, because of the plants they ate, their close cropping of forage, and the damage of their restless hooves as they stood close together in the heat of the day (Strong 1940: 275). As available range land diminished, the competition for access to it pitted cattle families against sheep families, and ranchers against homesteaders in what became commonly known as the "range wars." There was violence in Grant and Wheeler counties, although it was mostly against animals and property. in 1895, the Fossil Journal reported that "a sheep-hater burns 600 tons of hay on three farms near Mitchell." The Wheeler County News ran an account on May 27, 1904:

Poison was deposited in the range 8 miles east from town a short distance from the Canyon city road and the result of this cowardly act is that 12 head of range cattle belonging to Sigfrit Brothers dies last week.... Following the poisoning episode came the news to town early Monday morning that about 3 a.m. five men attacked the band of yearling sheep in the corral on the place belonging to Butler Brothers of Richmond. 106 sheep were killed and a great number were so wounded as to either die or have to be killed. These sheep were being grazed on leased land, and no motive can be found why this should occur.... (Fussner 1975: 93-94).

General homesteading and the fencing of the land — sometimes illegally on the public domain — also reduced the acreage available for running range cattle. The Oregonian noted in 1903:

Wheeler County differs from many other counties in Eastern Oregon where stock raising is the chief industry in having but little public range. Hills and valleys on every hand are generally fenced into great private pastures, and in these large herds are kept the year round, although the feeding of hay becomes necessary in the wintertime. In earlier times, the range was used largely for cattle, but now the range that is not enclosed with fences is more generally used by sheepmen (Fussner 1975: 94-95).

The Enlarged Homestead Act of 1909 encouraged further settlement in the area. A 1914 Department of Agriculture survey noted that 20 percent of range land in central, south-central, and southeastern Oregon had been homesteaded since 1910. The narrow, watered valleys of Grant and Wheeler counties offered conditions conducive to agriculture. As a result, Grant County witnessed a 33 1/2 percent decrease in cattle because of homesteading in the decade from 1904 to 1914, and Wheeler County saw a 60 percent decrease in cattle during that same period (Strong 1940: 261). Passage of the Stock Raising Homestead Act (1916), which allowed filing on up to one square mile of land, and the return of veterans following World War I who filed under that law, sped up the pace of homesteading on lands around the Monument, and put still more range lands under fence (Humphreys 1984a: 2).

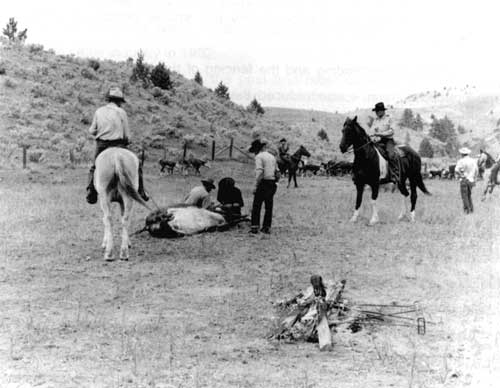

Fig. 44. Branding cattle in the John Day

watershed, n d (OrHi 99078, ODOT 4172).

The first steps taken to regulate the use of range lands came about indirectly through the establishment of national forest reserves. In Oregon, the earliest of these was the Cascade Forest Reserve, created by executive proclamation in 1893, comprising 4,490,800 acres and running from the Columbia River almost to the California line. The Blue Mountain Forest Reserve was created in 1906. Later it was subdivided into National Forests that now include Malheur, Umatilla, and Ochoco, part of each of these lying in Grant and Wheeler counties. Grazing by both cattle and sheep was allowed but controlled within the bounds of the forest reserves, where the region's high summer ranges were found. In the year 1900, permits for grazing became required, and starting in January of 1906, fees per head were charged. The fees were low at first — 18 cents per animal per season in 1911 — but increased in increments over the years. In return for the fees, cattlemen had access to carefully controlled summer ranges, parceled out through an allotment system, and scientifically managed to prevent depletion from overgrazing. Although cattlemen had initially opposed the creation of the forest reserves, by 1924 there was a general feeling that the Forest Service was successfully increasing the carrying capacity of the summer ranges (Strong 267-269).

A second important step toward regulation of range lands and a critical one in sustaining the cattle industry in Oregon, was passage of the Taylor Grazing Act of 1935. This piece of legislation affected 80,000,000 acres of the public domain in the West, eliminating all uncontrolled grazing. Thousands of acres of spring and fall range lands in Grant and Wheeler counties became subject to annual permits and fees. The Act specified that a high percentage of fees collected would be funneled back into communities for range improvements through local grazing districts (Strong 1940: 276-277).

The Depression and World War Two combined to swing the economic pendulum from sheep back to cattle ranching in central Oregon. The influx of homesteaders in the inter-war years, increased competition for range lands, falling prices, and labor shortages combined to make sheep ranching less profitable than cattle ranching. Many local ranchers, like the James Cant family and the Rhys Humphreys family, sold their sheep and switched to cattle in the years just before and just after World War Two (Taylor and Gilbert 1996: 39-40; Humphreys 1984a: 2-3).

Managing a cattle ranch in the middle years of the twentieth century was an increasingly complex enterprise. Herman Oliver wrote of his highly successful cattle operations near the town of John Day:

There isn't any system of ranch management, such as systems of bookkeeping. You can't say, "now do this and this and this and you will succeed." Management is thousands of little things, all tied together. Grass, hay, cows, water, weather, fences, calves, bulls, steers, markets, breeding, health, corrals — all these things must fit together like a machine. Any one of them, out of kilter, can cause the owner to lose his shirt (Oliver 1961: 108).

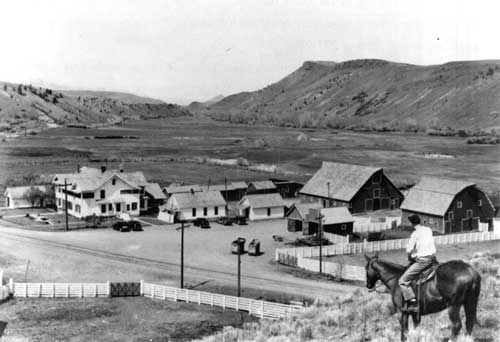

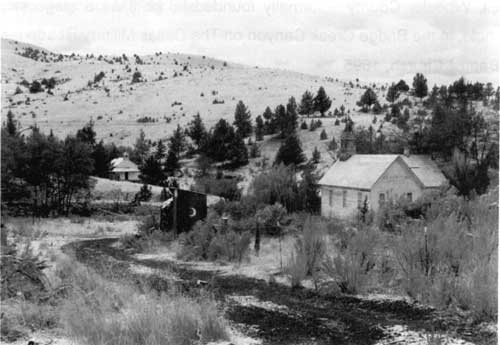

Fig. 45. View of the Oliver Ranch south

of John Day, n.d. (OrHi 100406).

Like the Cant Ranch, the Oliver Ranch required constant upkeep and repair. The Olivers routinely ended each year with planning for the next. They classified and inventoried all livestock, measured the hay and grain to determine if they had enough, estimated next year's sales, laid out the year's fencing and ditching program, inspected corrals and gates, mended fences, and repaired buildings. The Oliver's home ranch had thirteen buildings, "all exactly square with each other and all in good repair. We thought this helped in giving buyers a good first impression." Herman Oliver, like most cattle ranchers, was jack of all trades — a rough carpenter, blacksmith, machine repairman, and harness worker (Oliver 1961: 120)

Sheep Ranching

Introduced into central Oregon by pioneer ranchers in the early 1860s, sheep herds multiplied rapidly. Expansive grasslands with nearby stream courses for water and, by the mid-1880s, the advent of railroads, created an ideal setting for the new industry. Typically, sheep ranching involved the establishment of a home ranch or base, and location of a series of permanent, sheltered "sheep camps" adjacent to good grazing and water. Herdsmen were commonly responsible for between 1,000 and 2,000 head. Judith Keyes Kenny, whose family engaged in sheep raising for decades in Wheeler County, has commented: "Sheep are peculiar in the fact that they inspire strong emotions, either of affection or decided distaste. There is nothing romantic about the industry and all satisfaction must come from the work with the animals and the monetary gains" (Kenny 1963:104-105).

From the 1870s to the late 1930s, the production and management of sheep became one of the most important economic activities to develop in the upper John Day country. The build up of flocks, their management, shearing of wool, hauling of wool sacks, or driving of wethers and ewes to market were important occupations for decades. Local sheepman John Murray recalled in 1983 the impact of this enterprise in the vicinity of Dayville. He noted that there were forty-five or fifty thousand head of sheep within a radius of twenty miles. For every 1200 head of sheep, or band, there was a man with the sheep out in the hills at all the times, and there was a packer going back and forth for supplies at all the times (Murray 1984a: 18-19).

Many learned the sheep business as boys and moved directly into the work through accumulated experience. Sheep Rock area rancher Rhys Humphreys remembered:

Well, there was a lot of us kids started out at 12, 14 years old. The first year or two we would pack for a herder — take a pack string and stay with the herder all summer, learn his habits. After we did that a couple of years then we'd take a band. And you would start out at lambing time generally — go out about the first of April, or March, to lamb. Then you'd go to the timber with the sheep, and stay with them every day for a year or two, and you would have a little money.

In time, by saving, a young man could purchase his own flock and with careful management build it up (Humphreys 1984a: 3). James Cant, one of the more successful sheep ranchers of the early twentieth century in the region, started out with a $5,000 loan and a rented band of sheep, and from that built up his business. In the course of his lifetime, Cant secured 6500 acres of deeded land, and leased another 4500 acres of forest grazing allotments from the Bureau of Land Management (Murray 1984a: 14; Taylor and Gilbert 1996: 46).

Sheep production was time-intensive and all-consuming. Rhys Humphreys recalled that the job never ended, that someone had to be with the sheep twenty-four hours a day. He commented, "Your whole mind and concentration was on them sheep — everything. You had no outside interests whatever. If you did, then you wasn't a good hand" (Humphreys 1984a: 41-42).

Itinerant crews worked the countryside at shearing time. They traveled by buggy, saddle horse, or later automobile, working from ranch to ranch or establishing a base where herders brought in the flocks. John Murray described vividly the course of a day:

You sat down to your breakfast at six o'clock in the morning. You were ready to start the shearing machines at seven o'clock in the morning. You sheared until 11:30 a.m. and you went right back to work at one o'clock and you sheared until 5:30 p.m. and then you'd have your evening meal. You usually had ten men on your shearing crew and one man to grind the tools for you--to sharpen your tools. An old-time crew like that would shear, oh, an average maybe . . . 200 sheep in a day with the hand blades.

Fig. 46. Sheep shearers, tiers, and tool

sharpeners worked as itinerant laborers (OrHi 12,200).

With the advent of shearing machines, a crew might shear as many as 900 sheep per day. "That was a pretty good day's work for a crew of ten men," he concluded (Murray 1984a: 30-31).

The shearers were served by a man who tied the wool, usually one man for an entire shearing crew. Another employee of the shearing crew grabbed the tied fleeces and jammed them one after another into a large sack fastened into a round frame. From time-to-time he tromped on the fleeces to pack them, eventually building up a sack weighing about 320 pounds. The men then loaded the sacks into wagons to haul to the railheads (Murray 1984a: 32). Larger ranches developed modern technology to speed up shearing. Rhys Humphreys recalled the Cant Ranch modernization:

They originally started with an old one-cylinder engine, powered with a big power wheel and a belt drive. You had a drive shaft that run belts, and it was all belt driven. Then Cants finally got an old Fordston tractor that had a big power wheel, and they run their plant off that old Fordston tractor for years. It run a drive shaft and geared up so's they could run the tractor real slow, and the pulleys were geared to run the machinery real fast. We never got electricity until 1956 (Humphreys 1984a: 21).

One element that did not change much over time was castrating or " marking" lambs. Rhys Humphreys described the procedure: "There used to be 3000 lambs down at the W-4 [Ranch], 1500 here at the Munros', we'd have maybe 1500, and Cants would have 1200-1500. The wether lambs are all marked with your teeth, and I had good teeth. So some years I would help mark all these lambs right here." Humphreys recounted: "I had pretty good teeth. A lot of the others had false teeth or something and couldn't do it. Some years I'd mark as high as 15,000 lambs." His record was 1,200 in one day (Humphreys 1984a: 46).

The short-line railroads permitted herders to drive their flocks or their lumbering wagon laden with sacks of wool directly to the warehouses at railheads in Heppner and Shaniko. A vivid account described wool shipments at Grade, a stopping point and particularly steep slope on The Dalles Military Road in Wheeler County:

In good weather there were often ten, twelve, or even twenty freighters camping along the road from the house far up past the blacksmith shop. It was a sight to remember to see the Grade at starting time, lined with freight teams pulling out toward The Dalles, loaded with huge sacks of wool. Not a few outfits had as many as three wagons and ten or twelve horses (McArthur 1974).

Fig. 47. Wool buyers at the Henry

Heppner warehouse, Morrow County (OrHi 55,508).

The construction of The Dalles Scouring Mills, which operated from 1900 to 1920, was a further stimulus to the industry. This facility washed local wool prior to its export to weaving factories (Lomax 1950: 43-47).

The markets for wool from eastern Oregon were defined, in part, by the construction of woolen mills in the Willamette Valley and the extension in the 1880s of the Oregon Railroad & Navigation Company line along the south bank of the Columbia River. Ambitious investors erected a plant in 1867 for the Wasco Woolen Manufacturing Company to knit stockings, pants, shirts, skirts, blankets, and cassimeres. The facility endured repeated misfortunes: a washed-out reservoir, a boiler explosion, legal troubles, and a fire. It closed in 1869 (Lomax 1941: 287-296). In 1909 Charles P. Bishop and his sons purchased and expanded the Pendleton Woolen Mills for the manufacture of the famous Pendleton Indian blankets. The Bishops also had mills at Washougal and Vancouver, Washington, and Sellwood, Oregon. All these factories required wool and offered a potential market for the flocks of the upper John Day region (Carey 1922[2]: 503-504).

Statistical records chart the rise and fall of sheep production in the John Day watershed. The figures are incomplete — some agricultural census schedules did not enumerate all figures — but the overall trend for wool and sheep is clear, particularly the dramatic drops after 1930.

Table 4. Wool Production (lbs.), Grant and Wheeler Counties

| 1870 | 1890 | 1910 | 1930 | 1950 | 1979 | 1987 | |

| Grant County | 8,000 | 1,140,779 | - | 900,427 | 48,356 | - | 14,449 |

| Wheeler County | NA | NA | - | 973,689 | 97,311 | - | 13,574 |

(Bureau

of the Census 1872, 1895, 1913, 1932, 1952, 1987)

NA = Not Applicable (data not collected)

Table 5. Numbers of Sheep, Grant and Wheeler Counties

| 1870 | 1890 | 1910 | 1930 | 1950 | 1979 | 1987 | |

| Grant County | 1,154 | 237,346 | 202,073 | 120,437 | 4,715 | 1,600 | 2,065 |

| Wheeler County | NA | NA | 165,446 | 103,909 | 18,009 | 6,448 | 2,554 |

(Bureau of the Census 1872, 1895, 1913, 1932, 1952, 1987)

The decline of sheep ranching in central Oregon had much to do with the influx of new homesteaders in the 1910s and 1920s. Many of these new settlers entered the sheep business, only to find they were unable to secure grazing allotments in the nearby national forests, and their production, along with that of older established ranches, diminished prices. These economic realities and the onset of the Great Depression in 1929 hastened the shift from sheep to back to cattle ranching (Humphreys 1984a: 2-3).

Lumbering

Ponderosa pine, fir, and mixed conifers grew in abundance in the higher elevations of Grant and Wheeler counties. In the southern portion of Wheeler County around Camp Watson were stands of the especially valuable ponderosa, or yellow pine. The Strawberry Mountains of Malheur National Forest contained 90% ponderosa pine. Because of rugged terrain and the relatively late arrival of railroad and highway access, the John Day country saw little in the way of large-scale commercial lumbering activity in the nineteenth century. Early sawmills, water and steam-powered, easily supplied all local needs for building at mining camps and towns. At least one large cattle company — the Butte Creek Land, Livestock & Lumber Company — with holdings of 8,634 acres in Wheeler County, had timber interests in the area at a relatively early date (Anonymous 1902: 728; Shaver et al. 1905: 657; Southworth n.d.: 17).

By 1902, area citizens had entered into the debate on the creation of the Blue Mountain Forest Reserve. Boosters of local economic development saw the set-aside as a threat to the future of the region:

Citizens of Grant County are now petitioning the president in opposition to a proposed forest reserve which would include over half of its territory and all of its timbered areas. The future development of the county will depend largely upon the settlement of the forest reserve question, which is now pending (Anonymous 1902: 728).

Despite the public outcry, the Blue Mountain Forest Reserve was established in 1906. For ease of management, the reserve was divided into four national forests by 1908: Umatilla, Whitman, Deschutes, and Malheur. Settling "range wars" and fighting forest wildfires was the first order of business on the Malheur Forest, but commercial logging was not far in the distance. In 1922, the Malheur forest put up 890 million board feet of timber around Bear Valley for sale to the lowest bidder. It was the largest timber sale ever offered in the Pacific Northwest, and would involve the construction of hundreds of miles of railroad, lumber camps, and sawmills. Lumberman Fred Herrick made the low bid. Soon, accusations of fraud triggered a government investigation. The sale was offered for bid once again, and this time it went to Edward Hines (Mosgrove 1980).

The Edward Hines Lumber Company of Chicago came into southern Grant County in 1926. Through the Malheur Forest sale, the company gained an early monopoly on the virgin pine forest south of the Strawberry Mountains. The operation chose the little hamlet of Senaca in Bear Valley south of John Day as its corporate headquarters, where the company hotel still stands. A private railroad brought timber down to the enormous new mill at Hines in Harney County (Southworth, n.d.: 17-18).

The Chee Lumber Company acquired over 5,800 acres of timberland in Wheeler County and had holdings in the vicinity of the Clarno, Painted Hills and Sheep Rock units of the Monument. J.D. Welch, W.F. Slaughter, and Glenn E. Husted of Portland, established the company in 1923. Its stated purpose was to engage in sawmill operations, transport logs, and manage wharves. To that end, the company applied for and received a franchise to drive, catch, boom, sort, raft, and hold logs and lumber on the John Day River and its tributaries, from the junction of the North and Middle forks at Kimberly, all the way to the Columbia River. According to the franchise application, there were no existing "improvements" on those stretches of the river at that time. Chee Lumber built several booms and several splash dams. The uppermost dam — complete with a fish ladder protected by a game warden employee during spring salmon runs — was erected just above the town of Spray. By the end of 1925, Chee had taken out 200,000 board feet of forest products (Beckham 2000 a, b).

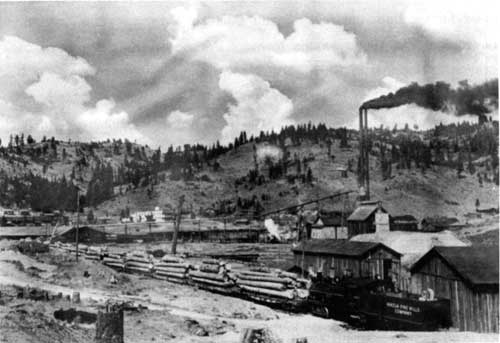

Fig. 48. Kinzua Pine Mills Co. at

Kinzua, Wheeler County, n. d. (Courtesy Fossil Museum)

Pennsylvania lumberman E.D. Wetmore first began acquiring timberland east of Fossil in 1909. In 1927, he established a sawmill in the ponderosa pine forest in an area he named Kinzua. The following year, the Kinzua Pine Mills co. built an extensive company town around the mill site. The community included 125 homes, a church, recreation hall with restaurant, barber shop, library, post office, tavern, company general store, and school. The community also boasted trout lakes for fishing, a scout camp and scout-house, and a common-carrier railroad that hauled passengers, mail, and sheep to Condon. At one time, Kinzua was the most populous town in Wheeler County, and employed some 330 workers in the mill (Stinchfield 1983: 12-13, 256).

The Kinzua Pine Mills Co. ran their own logging operation using a network of railroads into the forest, and later logging roads and trucks. As the operations pushed further from the mill, Kinzua built six logging camps, one of which survived into the 1960s as the town of Wetmore. Kinzua moved their mill operation to Heppner in 1953, and the town and mill were sold to new owners. The little railroad made its last run in 1976, and the sawmill, planing mill, and logging operations continued there until 1978. When the business finally closed its doors as the Eastern Oregon Logging Company, the town site was re-seeded by the Kinzua Corporation with 40,000 ponderosa pine trees (Stinchfield 1983: 12-13, 30, 256).

By the 1940s, there were several large companies operating in the area. Over the course of that decade, young men turned from ranching to higher paying jobs in the sawmills. Women filled in for men at the mills during World War Two, and many remained on the job beyond the War. By 1950, the timber industry had surpassed agriculture and ranching in the economy of Grant County. In Wheeler County, the Kinzua operation remained the mainstay of the economy until its final closure in the late 1970s (Taylor and Gilbert 1996: 40; Stinchfield 1983: 32, 256; Southworth n.d.: 18).

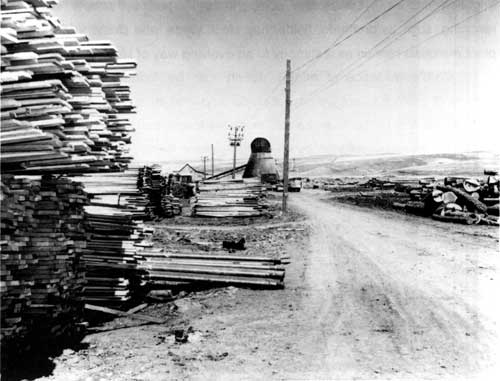

Fig. 49. The Howell Lumber Company at

Long Creek, Grant County, 1959 (OrHi 77490)

Cultural Resources Summary

Economic pursuits have left a most pervasive mark on the physical development of Grant and Wheeler counties. From the 1860s to the present day, mining, ranching, and lumbering have transformed the rural landscape with cultural imprints. Evidences of cattle and sheep ranching are perhaps the most visible today, spread across the valley of the John Day River and along high tributary valleys, where early settlement persisted and evolved into twentieth century operations. As is true in the context of early settlement, ranching resources encompass not only extant buildings and structures, but also smaller scale features such as fences, sheep bridges, corrals, cable crossings, and irrigation ditches. Landscape components shaped by people engaged in ranching, such as orchards, fields, hay stack yards, and clusters of ornamental plant materials remain as testimony to an evolving way of life.

Visible evidence of mining activity can be found in the mountainous corners of eastern Grant County, at placer and lode mine sites, in hillside ditches and tailings along the river banks, in ghost towns and remnant scatters. The timber industry is illustrated by sawmills, planing mills, logging camps, logging roads and railroads, scattered across the two-county region. Some are still operational, others reduced to surface artifacts. Hundreds of historic archaeological sites associated particularly with late nineteenth and early twentieth century mining and logging are located within the boundaries of the Malheur, Ochoco, and Umatilla forests. In twenty years of research and field work, Malheur Forest alone has identified some 3000 archaeological sites, including pre-historic sites.

Fig. 50. Postcard view of Mitchell, n.d.

(Courtesy Fossil Museum)

A secondary effect of economic development in the region was town building. Town layout, infrastructure, and historic buildings and structures reflect patterns of growth experienced throughout central Oregon. Towns took shape for economic reasons — they served as mining camps (Canyon City, Susanville, Granite), as company lumber towns (Bates, Senaca), or ranching service centers (Fossil, Dayville). Some gained standing as a stage stop by virtue of their location on a main arterial (Mitchell, Spray, Kimberly). Where primary economic activities continued or diversified, towns survived. Where primary economic activities died, hamlets quickly became ghost towns (Richmond, Antone). Within all of these communities, whether fleeting or permanent in character, are resources that illustrate ethnic diversity, social and political life, and commercial enterprise. Churches, mercantiles, hotels, schools, courthouses, and permanent homes are examples of these property types. Together they form clusters, or concentrated pockets of cultural resources that reflect certain periods of economic stability. Only one historic resource within the boundaries of the Monument associated with the theme of economic development is listed in the National Register of Historic Places:

The Cant Ranch, 1910-1976

Seven properties associated with economic development in the larger Grant and Wheeler county area are currently listed in the National Register:

The Kam Wah Chung & Company Building, built ca. 1867 with later additions, in John Day

The Thomas Benton Hoover House, built 1882, in Fossil, as the second, permanent home of the town's founder — the only designated property in Wheeler County

St. Thomas Episcopal Church, built 1876 in Canyon City, in the carpenter gothic style

Advent Christian Church, built 1898 in John Day

Fremont Powerhouse Historic District in the vicinity of Granite

Malheur National Forest Supervisor's House, constructed 1938 in John Day

John Day Supervisor's Warehouse Compound, dating from 1941

Fig. 51. Kam Wah Chung & Co.

Building, John Day. F.K. Lentz 1996 (National Park Service)

Many more resources associated with economic development are listed in the Oregon State Inventory of Historic Places for Grant and Wheeler counties (including some listings from both Umatilla and Malheur National Forests). A few of these sites are equally linked to transportation or settlement, and are thus also listed as inventoried resources in Chapter Four or Five:

In rural Grant County:

The Oliver Ranch — barns no. 1-3, granary, bunkhouse, and farmhouse, all ca. 1910

The Hines Lumber Company Railroad, 1940s

The Shangri-La (Ophir) Millsite — house, barn, and bunkhouse, ca. 1927

In Austin, Grant County — a stage stop on the road between John Day and Baker City:

The Linda Austin House — barn, store, rooming house, and outbuilding, from 1885-1909

The W.O. Meador Store, ca. 1900

In Bates, Grant County — a company town built in 1909 by the Sumpter Valley Railroad and the Oregon Lumber Company:

The Oregon Lumber Company Hotel, Sawmill, and Company Store — all ca. 1909-1910

In Canyon City, Grant County — founded in 1862, the earliest gold mining camp in John Day country, and briefly the largest city in Oregon, now the county seat:

Canyon City Brewery, 1870

Methodist Church, 1898

C.G. Guernsey Building, 1899

Jim's Antique Building, 1900

Greenhorn Jail, 1910

Fraternal Lodge Building, 1938159

Herman Putzien House, ca. 1880

J. Durkheimer Building, ca. 1885

Waldenberg-Schmidt House, ca. 1895

George Hazeltine House, ca. 1895

Canyon City Grade School, ca. 1900

In Dayville, Grant County — a stage stop on The Dalles Military Road, a ranching service center, and the venue for turn-of-the-century horse races:

Dayville General Store, ca. 1890

In Granite, Grant County — a mining town on the North Fork:

Doctor's House, 1880

Granite Country Store, 1883

Granite Meat Market, 1902

Granite Drug Store, ca. 1880

Wells Fargo Office, ca. 1880

General Store, ca. 1880

Granite Dance Hall

In Greenhorn vicinity, Grant County — now a mining ghost town:

Rabbit Mine District, ca. 1920

In John Day, Grant County — an early mining camp below Canyon City, remembered for its sizeable China Town, sustained by ranching and its central location on The Dalles Military Road:

Clarence and William H. Johnson Building, 1902

John Day Bank, 1904

John Day Opera House, 1914

On the Malheur National Forest in Grant County (note: hundreds of sites have been inventoried by the Forest, but are not included in the Oregon SHPO listings):

The Susanville Historic Mining District

Sunshine Guard Station, 1931

Stalter Mine Complex, 1935

Raddue Guard station, ca. 1930

Wray Lode Mine Complex, ca. 1940

In Mount Vernon, Grant County — a ranching service center on The Dalles Military Road and the John Day-Pendleton Highway:

David W. Jenkins Barn, ca. 1875

Ed Damon House, ca. 1890

Eastern Oregon Trading Post, ca. 1900

Mount Vernon Blacksmith Shop, ca. 1900

George Aldrich House, ca. 1910

In Prairie City, Grant County — an early mining town and ranching service center, railhead for the Sumpter Valley Railroad:

Methodist Church, 1885

IOOF Hall, 1902

Frank Kight Butcher Shop and Carriage House, 1902, ca. 1900

Prairie Hotel, 1901

Prairie City School and Gymnasium, 1939, 1931

Masonic Temple, 1911

Frank Flageollet House, ca. 1885

Moses Durkheimer General Store, 1901

Alex M. Kirchheiner Building, ca. 1901

Solomon Taylor Grocery, ca. 1902

Louis Parsons Store, ca. 1905

In Seneca, Grant County — a ranching hamlet at the head of Bear Valley, chosen as headquarters for the Hines Lumber Company in the late 1920s:

The Edward Hines Lumber Company Hotel, ca. 1940

On Umatilla National Forest in Grant County (note: other sites may have been inventoried by the Forest but not listed with the Oregon SHPO):

The Ruby Dugout Mining Site

Southeast Fourteen Mining Site

Ruby Bend Mining Site

Southwest Thirteen Mining Site

Ruby-Clear Creeks Confluence Mining Site

Clear Creek Strip Mine

Alamo Neighbor Mining Site

Keeney Mine

Ruby Creek Mining Cabins, 1930s

Forks Guard Station

In Fossil, Wheeler County — founded in 1876 as a ranching service center and stage stop, became the county seat in 1900:

Fossil Baptist Church, 1893

Fossil Mercantile Co. Building No. 1, 1896

Bank of Fossil, 1903

Fossil Mercantile Co. Building #2

IOOF Lodge #110, ca. 1905 — now houses the City of Fossil Museum

Fig. 52. Main Street in Fossil, city

hall on the left, n.d. (Courtesy Fossil Museum)

In Mitchell, Wheeler County — formally founded in 1873 as a stage stop and watering hole, in the Bridge Creek Canyon on The Dalles Military Road:

First Baptist Church, 1895

Mitchell State Bank, 1918

Mitchell School, 1922

Central Hotel, ca.1879

Wheeler County Trading Co. Store, ca. 1890

Misener & Magee Saloon, ca. 1895

Diana Reed House, ca. 1895

Henry H. Wheeler House, ca. 1900

Abdell Ramses Campbell house, ca. 1905

In Spray, Wheeler County — established in 1900 as a stage stop and ferry crossing:

Union High School #1, 1920

Spray Post Office, c. 1900

Community Church, ca. 1900

Baxter & Osborne General Store, ca. 1915

Area tourism literature listings for places associated with economic development, in addition to places listed above, include:

Stone Barn for Mt. Vernon, a local race horse, built 1877 along John Day River near Mt. Vernon

Richmond, a range hamlet in the Shoo-fly District, now a ghost town off SR 207

Wheeler County Courthouse, built 1901, in Fossil

Fig. 53. Ghost town at Richmond. F.K.

Lentz 1996 (National Park Service).

Several recommendations are made with regard to cultural resources associated with the context of Economic Development:

As proposed in Chapter Four, encourage and/or partner with the Oregon State Historic Preservation Office to conduct professional survey/inventory of historic properties in Grant and Wheeler counties. Current survey data is out-of-date, unsubstantiated, and terribly incomplete. An updated survey on ranching, mining, and logging would provide more solid site-specific data to better illustrate the contexts presented in this report, thus expanding the interpretive knowledge base at the Monument.

Consider sponsoring continuing scholarly research, perhaps in partnership with universities in eastern Oregon, on cattle and sheep ranch history in the area. Ranching, rather than mining and logging, is the historic theme most closely tied to Monument lands. Extant ranches along the John Day River north of Picture Gorge down to Clarno are of particular interest, as are large historic ranches, now broken up, of early cattle companies such as Gilman & French.

Little has been written of a substantive nature on the physical history of the communities of Grant and Wheeler counties. Consider working with the Grant County Historical Society and the Fossil Museum to sponsor a series of short but well-researched pictorial histories of the mining, ranching, and logging communities of the area.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002