|

John Day Fossil Beds

Rocks & Hard Places: Historic Resources Study |

|

Chapter Seven:

PALEONTOLOGICAL EXPLORATION

The John Day Fossil Beds have attracted the serious attention of scientists for nearly 140 years. The flora and fauna of past geological epochs, so remarkably preserved in the scattered sites of the upper John Day basin, have helped to chart the complex story of the earth's deep past. Prominent nineteenth and twentieth-century scholars have made pivotal discoveries in the John Day beds, leading to dozens of published reports, scientific articles, and scholarly papers. Specimens from the John Day deposits are held in paleontological collections around the world. Today, ongoing paleontological research at the Monument continues to build upon the pioneering work of the early scientists, and is best understood within the context of those efforts.

Thomas Condon, Pioneer Geologist

Thomas Condon, Congregational minister and amateur geologist, settled in The Dalles in 1861. Fascinated by fossil plants and vertebrates, Condon established a "cabinet" wherein he displayed the curiosities of nature. His interest encouraged others in the region to bring him their discoveries to see if he could identify the specimens. Condon's reputation grew rapidly. He read journals and books to expand his scientific knowledge, delivered public lectures in The Dalles, and eagerly greeted learned travelers when he knew they were in the city, inviting them to visit his home, view his collections, and share what they knew about geology and fossils. His keen collecting, avid research, good mind, and generous spirit helped generate local interest in the region's paleontology and, in turn, soon connected Condon with a national network of scholars and collectors (Clark 1989).

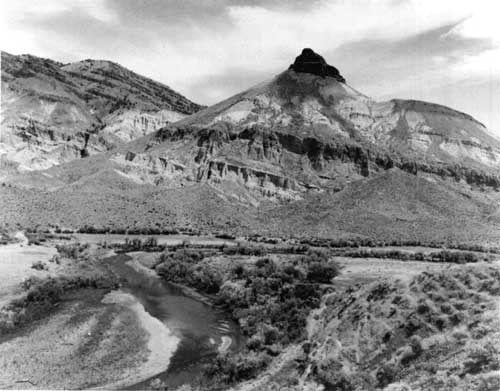

Fig. 54. View of Sheep Rock in the

"Turtle Cove," Sheep Rock Unit (OrHi 86089).

Condon's expeditions to the John Day country commenced in the fall of 1865 when he secured permission to travel with the U.S. Cavalry from Fort Dalles on a reconnaissance of the region. Condon collected fossils and rock specimens, including items from along Bridge Creek and from the locale around Sheep Rock which he christened "Turtle Cove." Following the expedition, Condon delivered lectures in The Dalles and Portland to share his discoveries (Clark 1989: 175-176). Whenever Condon could secure permission to travel with the military, he set out for the John Day country. In the fall of 1867, the editor of the Mountaineer (The Dalles, Oregon) reported on Condon's growing collection and that he had returned from the field with "new and beautiful geological specimens," several of which were "entirely new to the scientific world" (Clark 1989: 197).

Condon's reputation and knowledge of fossil deposits drew others to the region. In the late 1860s he had several visitors eager to see his collections. These included Clarence King and Arnold Hague, both engaged in work on the survey of the fortieth parallel for the U.S. Geological Survey. Graduates of the Sheffield School of Science, the preeminent program in geology at Yale University, King and Hague encouraged Condon in his work and reported his discoveries to others. William P. Blake, state mineralogist of California and a university professor, also met Condon and examined his fossil collection. Blake volunteered to take some of the fossils to colleagues in the East for identification (Clark 1989: 197). Blake shared the fossils with Dr. John S. Newberry, a scholar who had worked in Oregon during the Pacific Railroad Surveys in the 1850s, and James Dwight Dana of Yale. Newberry was so impressed that he solicited specimens from Condon for the Smithsonian Institution. Condon gathered items on the John Day, Bridge Creek, near The Dalles, and in the Columbia Gorge and, in February 1869, shipped them east (Clark 1989: 205-207).

Condon commenced formal sharing of information about the region in "Geological Notes From Oregon," an essay published in 1869 in the Overland Monthly and Outwest Magazine. The focus of this report was the great landslide which nearly dammed the Columbia River in the Cascades region of the Columbia Gorge. To assist his collecting further, Condon hired a rancher, probably Sam Snook who lived at Cottonwood on the John Day River, to assist in the fieldwork. In 1870 Condon sent additional specimens from Currant Creek, Bridge Creek, and McBee's Canyon — all sites in the upper John Day basin (Clark 1989: 207). Condon's observations and writing led to publication in 1871 of "The Rocks of the John Day Valley," also in the Overland Monthly.

Word of the fossil beds spread. In 1871 amateur geologist William de Gracey (Lord Walsingham) passed through the upper John Day while on a hunting expedition. De Gracey collected specimens at Turtle Cove and Bridge Creek, some of which were noticed in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London (Bettany 1876: 259).

In 1871 Othneil C. Marsh, professor of paleontology at Yale, led the first university-sponsored scientific expedition to the John Day Fossil Beds. Condon had corresponded regularly with Marsh and shipped specimens to him. Marsh arrived in October with a dozen Yale students, all weary after weeks in the field in Kansas and Wyoming. The Yale party traveled 600 miles by lurching stagecoach from Salt Lake City to Canyon City, arriving on October 17. A military escort from Fort Harney accompanied them to the John Day deposits, where they were met and guided by Thomas Condon. In spite of their fatigue and deteriorating weather conditions, the students and their professors, accompanied by Condon, collected eleven boxes of material between October 31 and November 8. The group then moved on to The Dalles where Marsh studied Condon's collection for three days. Marsh was particularly intrigued with the bones of a three-toed horse and tried to purchase the specimen; Condon declined to sell it. Subsequently Marsh published on the specimens viewed or collected during the 1871 expedition. The species included two rhinoceros and one oreodon, the latter a specimen presented by Condon to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University (Clark 1989: 236-237; Schuchert and LeVene 1940: 124-126).

Condon's circle of contacts continued to grow. His connection with Marsh led to correspondence in 1871 from Edward Drinker Cope of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Cope, a rival and at times a bitter foe of Marsh, wanted specimens. Next came a request from Professor C. D. Voy of the University of California, Berkeley, volunteering to exchange fossils from California for those Condon was finding in Oregon. At almost the same time, Joseph Le Conte of the University of California announced a trip to Oregon and proposed that Condon join him in the field (Clark 1989: 230-235).

In less than five years, Condon's pioneering geological work had attracted major American scholars. He had linked them through correspondence and specimens to the unique deposits of the John Day region. Governor Lafayette Grover in 1872 named Thomas Condon Oregon's first State Geologist, a position which ultimately led to his leaving the ministry and assuming professorial responsibilities at the new University of Oregon in Eugene (Clark 1989: 252-254).

Scientific Expeditions in the Late Nineteenth Century

The interest of scientists, students, and scholars in the John Day region deepened during the latter part of the nineteenth century. 0. C. Marsh and Oscar Harger of Yale University mounted a second expedition to the fossil beds in the fall of 1873. Marsh thereafter arranged for local residents Leander S. Davis, Sam Snook, and William S. Day to continue collecting for him in the John Day country. Between 1873 and 1877, they forwarded him boxes of vertebrate remains from the fossil beds (Schuchert and LeVene 1940: 181). The results of Marsh's two expeditions to Oregon and work with the Condon collection led to an article "New Equine Mammals from the Tertiary" published in 1874 in the American Journal of Science. In it Marsh discussed five genera of horses. Three — Miohippus, Parahippus, and Merychippus — were specimens collected by Condon (Clark 1989: 256-257).

Edward Drinker Cope, paleontologist for the U.S. Geological Survey of the Territories, began fieldwork in the American West in 1872 in Wyoming. To expand his operations into Oregon he sent Charles H. Sternberg, who had labored on surveys in Kansas, to the upper John Day region in 1877. Cope's subsequent effort to identify, assess, and publicize the fauna of the upper John Day region was prodigious. Between 1878 and 1889 he submitted over thirty papers to professional journals.

In 1884 Cope published a massive, two-volume study, The Vertebrata of the Tertiary Formations of the Far West, part of the Report of the United States Geological Survey of the Territories orchestrated by F. V. Hayden. The Cope report confirmed an extensive collection of specimens of what he termed "The John Day Fauna" of Oregon. The specimens that were analyzed (and sometimes illustrated) included dozens of species.

Many of the assessments supplied details on the source of the remains. Writing about Galecynus latidens, Cope noted: "The typical specimen described was obtained by Mr. J. L. Wortman in the cove of the John Day valley, Oregon, in the John Day Miocene formation. One of the mandibles was found by Mr. C. H. Sternberg" (Cope 1884[1]: 931). Cope's commentary was often vivid. Writing about the panther Nemravus gomphodus, he commented:

Nevertheless, this species did not probably, attack the large Merycochoeri of the Oregon herbivores, for their superior size and powerful tusks would generally enable them to resist an enemy of the size of this species. They were left for the two species of Pogonodon, who doubtless held the field in Oregon against all rivals" (Cope 1884[1]: 972).

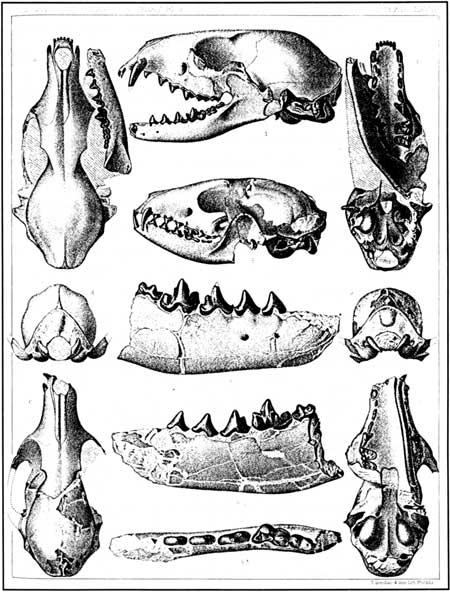

Fig. 55. Canidae from the Jon Day epoch

of Oregon (Cope 1884[2]: Pl, LXVIII).

Cope's handsomely illustrated volumes elevated the fossil beds of the John Day country to national status. Scientists in the United States, indeed in other countries, could now see the wide range and quality of fossils preserved in the deposits. Cope's illustrators dutifully captured the remains, showing details of dentition, skull structure, arm and leg bones, ribs and vertebrae, and other features. The vivid writing and cross-references to similar species in other locations and citations to scientific publications gave the Cope reports utility. Their publication by the Government Printing Office made them affordable and available to libraries and scholars.

Charles H. Sternberg, Cope's able associate, journeyed to the John Day Fossil Beds in the spring of 1878. Sternberg had camped during the winter of 1877-78 on Pine Creek in Washington Territory. In April he visited Fort Walla Walla where his brother, Dr. George M. Sternberg, was serving as post surgeon. From there Sternberg traveled by wagon to the John Day watershed with his two assistants, Joe Huff and Jacob Wortman. The men crossed from the Powder River country over the Blue Mountains to the John Day in the vicinity of Canyon City where, in May, 1878, they observed extensive placer mining still underway (Sternberg 1931: 170-171).

The party stopped first to collect fossil leaves on the Van Horn Ranch, about seven miles east of Dayville. "I collected two hundred specimens," wrote Sternberg, "and Mr. Wortman eighty-five. They were all very fine, and represented the oak, the maple, and other species. I secured some fish vertebrae also." In mid-May the men were at Dayville where they hired Bill Day and Mr. Warfield, local residents who had collected for Professor Marsh. The party arrived at Picture Gorge. Sternberg later wrote of Turtle Cove:

At the foot of this canyon, the mountains swing away from the river in a great horseshoe bend, closing in upon it again several miles below. The brilliantly colored clays and volcanic ash-beds of the Miocene of the John Day horizon paint the landscape with green and yellow and orange and other glowing shades, while the background, towering upward for two thousand feet, rise rows upon rows of mighty basaltic columns, eight-sided prisms, each row standing a little back of the one just below, and the last crowned with evergreen forests of pine and fir and spruce. But no pen can picture the glorious panorama" (Sternberg 1931: 173-174).

Sternberg and Wortman maintained an informal base of operations at the Mascall Ranch south of Picture Gorge — at the present south boundary of Sheep Rock Unit — making collecting forays of several weeks duration into Turtle Cove. Mascall allowed the scientists to make use of an extra log cabin behind his own for the storage of their supplies and specimens. Sternberg later remembered the generosity of the Mascall family that summer:

This Mr. Mascall had a wife and daughter, and when we came in from the fossil beds, after several weeks of camping out, it seemed almost like coming home to be able to put our feet under a table, eat off stone dishes, and drink our coffee out of a china cup, and to sleep on a feather bed instead of a hard mattress and roll of blankets.... Mascall was a good gardener, and always had fresh vegetables, a most enjoyable change from hot bread, bacon, and coffee. I shall not soon forget his hospitality (Sternberg 1931: 178-179).

Sternberg and Wortman reached the fossil beds in Turtle Cove by packing their gear over the top of Picture Gorge on an old horse trail, dropping down steep slopes to "Uncle Johnnie Kirk's hospitable cabin, a 12 x 14 structure of rough logs with a shake roof. He kept a bachelor's hall and lived all alone except when some cowman or fossil hunter came along. We pitched our tent near his house."

Sternberg's field strategy was to climb to the inaccessible heights, a "perilous enterprise" as he phrased it, to put his searching above the reach of previous fossil collectors. "I could tell of a hundred narrow escapes from death," he later recalled when assessing the perilous work. 'What is it that urges a man to risk his life in these precipitous fossil beds? I can only answer for myself," he later wrote, "but with me there were two motives, the desire to add to human knowledge, which has been the great motive of my life, and the hunting instinct, which is deeply planted in my heart" (Sternberg 1931:173-200).

The following year, Jacob L. Wortman had charge of Cope's exploring party in central Oregon which made "extensive and valuable collections of the fossils of the John Day . . ." (Cope 1884[1]: xxvi-xxvii). Wortman, subsequently professor of paleontology at Yale University, was the son of Jacob and Eliza Ann (Stumbo) Wortman, overland emigrants to Oregon in 1852. Wortman was a partner with his father and three brothers in Jacob Wortman & Sons, with mercantile stores in Junction City and Monroe, Oregon. With the dissolution of the firm in 1883, Jacob L. Wortman founded the First National Bank of McMinnville and his son, Henry, invested in Olds, Wortman, and King, a major retail store in Portland. Wortman committed his life to teaching, research, and writing (Anonymous 1903: 589-590).

Leander S. Davis, an experienced local collector, served as a guide for every major expedition to the John Day Fossil Beds into the early twentieth century. Davis accompanied Wortman and Sternberg in 1878-79. He guided Captain Charles Bendire, of the U.S. Army garrison at Fort Walla Walla, in the collection of fossil plants in 1880. Davis again collected in 1882 for the U.S. Geological Survey under the direction of Othneil Marsh (Shotwell 1967: 12).

William Berryman Scott of Princeton University made a large collection in the John Day region in 1889 with the help of Leander Davis. "The success of the expedition," recalled Scott, "was very largely due to Davis whose knowledge of the country and of the fossil beds was very exact." The Scott party camped at a pine grove in the "Cove" and from there made daily expeditions to seek fossils. The men found the country "sheeped off," virtually denuded of grass through overgrazing. Philip Ashton Rollins served as photographer. He had to cope with curtains of smoke pouring through the region from distant fires in the Cascade Range. Scott estimated that the work yielded a ton and a half of specimens. These were shipped to Princeton University and stored in the basement of Nassau Hall. The cleaning, mounting, and study of the collection was deferred and, before it could be done, pipe fitters installing a heating system in the building pillaged the boxes. Scott subsequently observed: "it is maddening to think of what was lost through the brutality of ignorance after all our trouble in gathering it" (Scott 1939: 173-177).

By the close of the nineteenth century, news of the John Day Fossil Beds had spread through the scientific community to far corners of the world. J. Arnold Shotwell, University of Oregon geologist at the Museum of Natural History, has commented: "By 1900 over 100 papers had been published on the geology and paleontology of the John Day Basin and nearly every major museum in the world had collections from there." Most of these studies focused upon the naming of new species or genera (Shotwell 1967: 12).

Early Twentieth Century Research

In the twentieth century a new generation of collectors and writers worked with the specimens of the upper John Day region, expanding knowledge of the relationships between vertebrate faunas and the basin's stratigraphic sequence. John Campbell Merriam of the University of California, subsequently president of the Carnegie Institution in Washington, D. C., began his fieldwork in 1899. The first University of California expedition included Merriam, its director, Loye H. Miller, a naturalist, F. C. Calkins, geologist, Leander Davis, local guide and (by then) sawmill operator out of Baker City, and George B. Hatch, a hunter and fisherman. The party traveled via The Dalles Military Road into the Bridge Creek area. The men established a base camp at Allen's Ranch, noted as six miles south of the mouth of Bridge Creek and two and one-half miles southeast of the wagon road. The group made at least two more camps in Turtle Cove to work the John Day Formation (Anonymous 1899). Merriam's work concerned the relationship of fauna to geology. His discerning observations led to descriptions of several salient features of the deposit areas: river terraces, Columbia lava, John Day Series, and the Clarno, Mascall, and Rattlesnake formations.

Merriam's integration of fauna and geology influenced his students, Eustace Furlong, Chester Stock, and Ralph Chaney who mounted additional expeditions in 1900, 1901 and 1916. They published a collaborative work, "The Pliocene Rattlesnake Formation and the Fauna of Eastern Oregon" (Merriam, Stock and Moody 1925). Erling Dorf of Princeton University recalled in 1979 that he had served as an assistant for Ralph W. Chaney in the Mascall and Clarno formations, "probably in 1926 or 1927," (Dorf 1979).

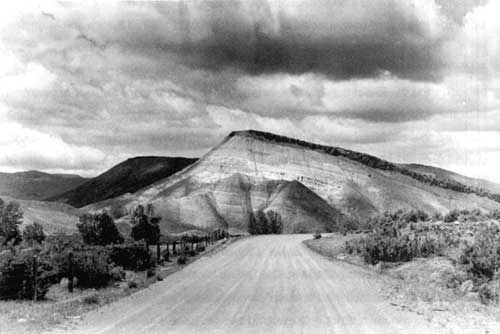

Fig. 56. View of Carroll Rim on Bridge

Creek, Painted Hills Unit (OrHi 57789).

Geologist Ralph Chaney devoted much of his field time and research to the flora of the lower John Day Formation found in the Bridge Creek region. "It soon became clear," noted J. Arnold Shotwell, "that this basin provided an ideal set of circumstances for sequencial [sic] floristic studies and in the next forty years Chaney took advantage of these to produce a series of highly significant papers providing the basis for much of modern paleobotany" (Shotwell 1967: 13). Chaney's works included "Quantitative Studies of the Bridge Creek Flora" (1924), "Geology and Paleobotany of the Crooked River Basin" (1927), and "The Ancient Forests of Oregon" (1948).

In 1906 the University of Kansas sponsored an expedition to the John Day region. C. E. McClung, Martin, Baumgartner, and Hoskins — members of the Zoology Department — crossed the Blue Mountains to the John Day on July 1 and established a base camp at Turtle Cove. "Almost all colors of the rainbow may be seen, but the prevailing ones are chocolate red and pea-green," wrote McClung. The Kansas contingent worked diligently. "It is a very difficult matter to remove the bones in good condition because of the lack of homogeneity in the matrix," observed McClung, but he hastened to add that the bones were "in an excellent state of preservation and make beautiful specimens." The specimens went to the holdings at the University of Kansas (McClung 1906: 67-70).

During the summers of 1925, 1930, and 1934 the California Institute of Technology mounted expeditions to the John Day region. In 1940 its students and professors joined an expedition with the Carnegie Institute of Washington, D.C. The specimens were transferred in 1959 to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (Whistler 1979).

Deposits near Clarno, Oregon, provided important paleobotanical information. The deposits were first discerned about 1890 and led to the publication of "Fossil Flora of the John Day Basin" (Knowlton 1902), a monograph discussing twenty-two forms of leaves. In 1942 Thomas J. Bones commenced his paleobotanical work in the Clarno deposits. Bones later stated that over fifty different genera had been identified but that "many hundreds of species are now extinct, rendering identification to modern genera difficult to impossible" (Bones 1979: 5). In 1942, dedicated amateur geologist Lon Hancock found a fossil tooth in the Clarno "nut beds" along Pine Creek. R.A. Stirton of the University of California soon identified the tooth as from the rhinoceros Hyrachyus in the first account of animal remains from the Clarno beds (Shotwell 1967: 14). In 1956, Hancock discovered mammal fossils about one mile from the nut beds, and subsequently excavated a large site now known as the Hancock Mammal Quarry. Investigations at the mammal quarry continued into the 1980s, yielding a highly diversified fauna (Fremd, Bestland, and Retallack 1994).

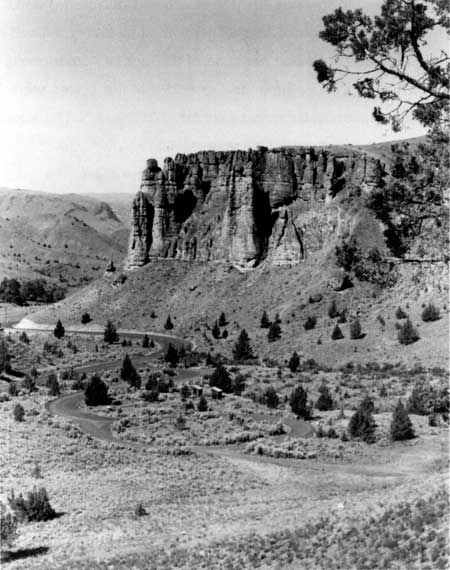

Fig. 57. View of eroded rock palisades

at Clarno Unit (OrHi 101197)

Recognizing Educational Values

By mid-century, the tremendous potential of the John Day fossil beds as an educational resource for the general public was widely acknowledged. Beginning in 1931 and continuing through 1965, the State of Oregon made careful purchases of key parcels of land with high interpretive potential. The result was the creation of three roadside parks with unique paleontological resource values: Picture Gorge, Painted Hills, and Clarno state parks (Mark 1996: 41-82).

J. C. Merriam, whose interest in the John Day region endured for more than four decades, organized the John Day Associates in 1943. In addition to coordinating scientific research projects in the upper basin, this group was committed to conservation and to "developing public interest in the geological story so clearly told by the rocks and fossils of the region." The "Associates" thus advised Samuel Boardman, superintendent of the Oregon State Parks system, on which tracts to acquire for park purposes (Shotwell 1967: 23).

In 1951, the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry established a field school on public lands in the vicinity of Clarno. Camp Hancock, named for pioneer Clarno fossil collector Lon Hancock, served (and continues to serve) as a summer educational facility for young scientists from elementary to graduate school levels. The camp originally operated with a forty-acre lease from the Bureau of Land Management, but the acreage was reduced to ten in 1969 (Mark 1996:115).

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument was established in 1975, following a campaign of nearly ten years. Its stated purpose was set forth in the Monument's strategic plan:

To protect the paleontological resources of the John Day Basin and provide for, and promote, the scientific and public understanding of those resources (Mark 1996: 9).

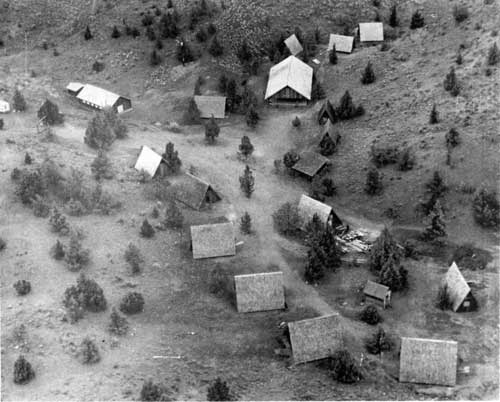

Fig. 58. Early view of Camp Hancock, on

display at Berrie Hall; F.K. Lentz 1996 (National Park

Service).

A detailed administrative history of the Monument, and its formation from three predecessor state parks, are thoroughly documented in Floating in the Stream of Time: An Administrative History of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument (Mark 1996). The impetus for creation of the Monument clearly lay in the nationally recognized significance of its paleontological resources and their educational potential.

The John Day Fossil Beds remain the focus of worldwide scientific research even today. Much of that outside research is directly facilitated by the Monument's own paleontology program. Internally, management of paleontology resources continues to be the Monument's top priority, in accordance with the park's primary mission. The paleontology program has greatly expanded over the years to encompass field prospecting, fossil recovery, curation of specimens, research, interpretation, survey of other collections, past and present literature reviews, coordination of field investigations by outside institutions, and cooperative agreements for management of paleo-resources on federal lands outside Monument boundaries (Mark 1996: 217-227).

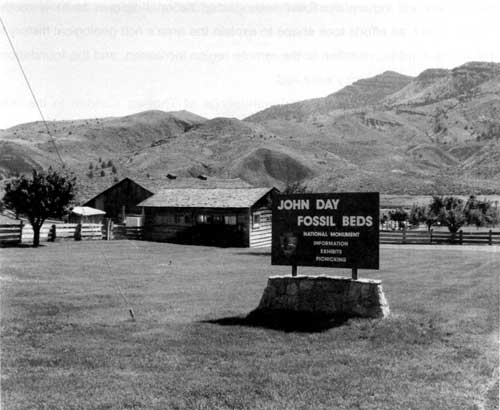

Fig. 59. Headquarters, John Day Fossil

Beds National Monument, Sheep Rock Unit, F.K. Lentz 1996 (National Park

Service).

Cultural Resources Summary

Paleontological explorations constitute an exceptionally important theme in the human history of the John Day basin. Belatedly explored and sparsely settled due to its difficult access, the region was bypassed by some of the larger events of Pacific Northwest history. Other themes of the area's economic development — mining, ranching, and logging — have played a sustained but less visible role. None constitute the region's claim to fame in the wider world. By contrast, the fossil beds and their exploration have placed Grant and Wheeler counties in the limelight for more than a century. As a destination for scientific exploration and inquiry, the fossil beds gained national renown as early as the 1870s. Later, as efforts took shape to explain the area's rich geological history to the general public, visitation to the remote region increased, and the foundations of a local tourism industry were laid.

From the first documented wanderings of Thomas Condon in the mid-1860s, through the mid-twentieth century and beyond, visiting scientists and scholars have camped, prospected, and labored in the vicinity of the Monument. Some of their field journals and subsequent articles mention the places where they camped or searched for fossils. But most of these references are frustratingly vague, describing only general localities and nearby geographic features. Such broad references are made in the literature to Condon's explorations in the vicinity of Bridge Creek and around Sheep Rock in Turtle Cove, and to J.C. Merriam's forays into the Blue Basin. Somewhat more specific are references to particular places which served as base camps or prospecting sites. These include Sternberg and Wortman's 1878 collections at the Van Horn Ranch, and their base camp at the Mascall Ranch south of Picture Gorge, as well as J.C. Merriam's 1899 base camp at Allen's Ranch on Bridge Creek and prospecting on the Loup Fork (Mascall) beds on Cottonwood Creek.

Fig. 60. Berrie Hall at Hancock Field

Station; F.K. Lentz 1996 (National Park Service).

The presence of these visiting scientists and their interactions with local ranchers was nonetheless transitory, most lasting no longer than a few days or a single season at most. In their travels through the upper John Day basin, small parties of fossil hunters left no visible marks on the land. Because of this transient use and lack of location specificity, sites associated with fossil hunting are problematic in terms of identification and evaluation for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. The level of detail required to ground-verify locations of camps and collecting sites has not been uncovered in this study. Thus, no sites of this category within the Monument or its general vicinity have thus far been identified as eligible for listing in the National Register.

Within the boundaries of the Monument one site does appear to have clear potential for listing in the National Register in the near future. Camp Hancock (now called the Hancock Field Station) is a ten-acre inholding within the Clarno Unit, owned and operated by the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry. Now nearly fifty years of age, Hancock Field Station is a specific locale that has played a continuing role in paleontological research since 1951. Even more critical has been its role in science education for the general public. The camp complex includes Berrie Hall, a board and batten-clad dining and assembly hall, the oldest structure on site. Arranged around Berrie Hall in a narrow canyon are various laboratories, display sheds, and housing in the form of clusters of small A-frame cabins. The camp's simple wood-frame buildings were added over time, the most recent additions being A-frames brought in from Rajneeshpuram, the failed religious commune at Antelope.

Recommendations for further investigation of cultural resources associated with the context of Paleontological Explorations include:

Encourage and/or assist Oregon Museum of Science and Industry in documenting the historical development of Hancock Field Station for possible nomination to the National Register, when the facility reaches fifty years of age in 2001. Consider potential inclusion of nut beds and mammal quarry as associated paleontological features.

Provide closure to the question as to whether sufficient site-specific information exists for National Register determinations of eligibility, by documenting all locales associated with the movements of pivotal early-day fossil-hunters in the vicinity of the Monument. Using expedition journals and historic field photographs, revisit base camps, field camps, prospecting locales, and important discovery sites. Wherever possible, verify, map, and photographically record precise locations. Assess for significance within overall context of paleontological explorations in the John Day basin.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

joda/hrs/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 25-Apr-2002