|

KATMAI / ANIAKCHAK

Isolated Paradise: An Administrative History of the Katmai and Aniakchak National Park Units |

|

| PART II: ANIAKCHAK NATIONAL MONUMENT AND PRESERVE |

Chapter 14:

Aniakchak and the Alaska Lands Question

During the 1960s, the National Park Service administered only four units in Alaska: Mount McKinley National Park and Katmai, Glacier Bay, and Sitka national monuments. Although all four units had been incrementally increased in size over the years, no new area had been created since 1925. For decades afterward, the agency had been unable to maintain even a token presence in the various Alaska national monuments, but in the 1950s an increasing NPS budget, the implementation of the Mission 66 program, and pressure from Alaskan development interests had brought about the construction of the first visitor facilities.

In January 1964, George B. Hartzog, Jr. became NPS director. Hartzog wanted to be sure that the "surviving landmarks of our national heritage" would be protected, and recognized that if any significant park system growth was to occur, that growth would have to be in Alaska. That November, therefore, he appointed the so-called Alaska Task Force--composed of Sigurd F. Olson, Robert S. Luntey, George L. Collins, Doris F. Leonard, and John M. Kauffmann--to prepare an analysis of "the best remaining possibilities for the service in Alaska." The report that emerged from that effort, called Operation Great Land, evaluated 39 zones and sites across the state which contained recreational, natural, or historic values. It was the first report to contain a statewide survey of areas which had park potential. Two of those areas were the Aniakchak Crater Zone and the Mt. Veniaminof Zone, both of which had been proposed as national monuments in 1931. The Aniakchak Crater Zone, which was "possibly 20 miles square," was nominated because it was "one of several recently active volcanoes on the Alaska Peninsula and Aleutian Chain which possess symmetrical beauty and possibly other values warranting conservation and/or interpretation." [1]

In 1966 the NPS asked Roger Allin, a longtime Fish and Wildlife Service employee in Alaska, to prepare his own recommendations for future parks. Allin's report, entitled Alaska: A Plan for Action, was relatively brief, and suggested the creation of just four new park areas. Those areas were roughly equivalent to today's Wrangell-St. Elias, Gates of the Arctic, and Lake Clark NPS areas, along with Wood-Tikchik State Park. He mentioned the Aniakchak area in his report, but suggested that it be considered for parkland "at some future date." Allin also suggested that NPS officials pay "early attention" to the Service's two landmark programs. [2]

In 1967, the agency responded to Allin's recommendations when the Aniakchak area was evaluated by the National Natural Landmarks Program. This program, which was created by the Secretary of the Interior in 1962, was intended to identify and encourage the preservation of areas with unique and significant natural values. For its first several years, the program did not apply to Alaska. Then, on May 3, 1967, Assistant NPS Director Theodor Swem made $20,000 available to the University of Alaska to study potential sites in the state. The Aniakchak and Veniaminof areas were among ten sites which were examined that year. [3] Alaskasearch, the company which evaluated the various sites, felt that Aniakchak Crater was fully eligible as a national natural landmark. Ellis Taylor, the author of the report, noted that

Aniakchak, the real estate agent would say, has everything. Scientific importance, popular appeal, dramatic, heroic proportions, a mysterious past and an unpredictable, possibly spectacular geologic future, even hot and cold running water.

The consultant found that "From no viewpoint is Aniakchak unimpressive," and it stated that the crater "is recognized by geologists as an outstanding feature, unmatched in many ways, by volcanic phenomena of far greater renown." The report's recommendations were quickly seconded by Interior Department officials. In November 1967 the NPS, which was responsible for carrying out the NNL program, approved the designation of Aniakchak Crater as a National Natural Landmark. The 20,000-acre site, however, could not receive official designation until it received the Interior Secretary's approval. In 1969, former Alaska governor Walter Hickel became the Interior Secretary, and in August 1970 he gave final approval to the NNL designation. The landmark was later renamed Aniakchak Caldera. [4]

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the NPS continued to formulate plans to create new parklands in Alaska. As noted in Chapter 5, the agency proposed several new park units during the waning days of the Johnson administration, and one monument extension--at Katmai--was implemented. Other park proposals, propounded by both the Interior Secretary and by Alaska's Congressional delegation, did not survive. None mentioned Aniakchak. [5]

In November 1971, NPS personnel produced two rough blueprints for future Alaska parklands. Richard Stenmark, an Anchorage-based employee who had served as an advisor to Secretary of the Interior Walter Hickel, laid out a "National Park System Alaska Plan" which included a list of potential historical, natural, and recreational areas in the state. That same month, Director Hartzog produced a map of potential national parks and monuments. His map, in many ways, paralleled Stenmark's list. Hartzog, however, envisioned an Aniakchak Crater National Monument, whereas Stenmark failed to include it. [6]

Interior Department Boundary Proposals

A month later, on December 18, 1971, President Nixon signed into law the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act. As noted in Chapter 5, the act set into motion nine years of activity regarding the disposition of Alaska's federally-managed lands. The Department of the Interior was the focus of activity for the first several years after ANCSA's passage. Intense debate took place over the number of acres that would be divided between Federal agencies, the State of Alaska, and various Native corporations; within the Federal government, equally intensive debate took place between the NPS, the Fish and Wildlife Service (and its Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife), the Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Forest Service. The various agencies made their recommendations by 1975; not until 1977, however, did Congress confront the Alaska lands question. As shall be seen, Congress was unable to come up with a workable plan during the seven-year period which ANCSA had designated for that purpose. President Carter, therefore, allowed for a continuation of Congress's deliberations when he created a series of national monuments in December 1978. The House passed its version of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act in May 1979. In August 1980, the Senate passed a somewhat different bill. Shortly after Reagan's election in November, the House agreed to the Senate's version, and Carter signed the bill into law on December 2.

The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act stated that any lands proposed for one of the four conservation systems (the so-called "d-2" lands) had to be withdrawn within nine months, and Interior Department officials recognized that a preliminary land withdrawal needed to be made within ninety days. Based on those deadlines, the NPS had no time to waste in beginning its planning effort.

In late December, Richard Stenmark flew to Washington, and by January 4 he had completed an initial identification of NPS interest areas. The January list was based, to a large extent on his November 1971 compilation. Significantly, however, the November list had omitted Aniakchak; two months later, however, he included a 167,000-acre Aniakchak Crater unit.

The NPS was not the only agency which coveted the area. On January 7, the Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife released its own list of interest areas; Aniakchak Crater was included on that agency's "wish list" as well. [7] That conflict was eliminated in favor of the NPS on March 9, when Interior Secretary Rogers C. B. Morton withdrew approximately 80 million acres of "d-2" lands. Fourteen areas, comprising 33.4 million acres, were withdrawn to the NPS. One of those areas was Aniakchak Crater, which comprised 279,914 acres--over 100,000 acres larger than Stenmark had originally recommended in January. Areas outside of the March withdrawal area were open to selection by the state or by Native corporations. [8]

The NPS, hoping to learn as much as they could about the lands in and around the March withdrawals, commenced a review of applicable lands soon afterwards. The agency created the 35-member Alaska Task Force, whose purpose it was to compile available information about the proposed park units. The ATF was subdivided into several teams. Team 4, organized to fashion reports for the Aniakchak, Katmai, and Lake Clark proposals, consisted of Urban E. Rogers, John Dennis, James Isenogle, and Keith Trexler. [9]

In July, in a meeting with Secretary Morton, the ATF recommended that eleven areas, totalling 48.9 million acres, be studied as additions to the NPS system. One of those areas, Aniakchak Crater, was to extend out over 740,240 acres, almost three times the size of what Morton had withdrawn four months earlier. [10] Renewed efforts then began to balance the demands of the various conservation agencies. On September 13, at the end of the nine-month deadline imposed by ANCSA, Morton withdrew 79.3 million acres for the four conservation systems. The share he recommended for inclusion into the NPS, 41.7 million acres, was midway between what the agency had been provided in the March withdrawal and what it had requested in July. But the Aniakchak Crater withdrawal, at 740,200 acres, remained almost as large as NPS leaders had recommended in July. The monument included much of today's monument and preserve; in addition, it included Cape Kumliun, the Weasel Mountain area, and much of the Meshik River valley. [11]

Provisions in ANCSA decreed that by December 18, 1973, the Secretary of the Interior had to issue a final legislative recommendation on which Alaska lands would be considered for the four conservation systems. In order to effectively fulfill that recommendation, intensive study of each area would be needed. A conceptual master plan, a draft environmental statement (DES), and detailed legislative support data would have to be completed by that date for each area. The NPS had already spent time in the field gathering data intended to meet the September 1972 deadline. Additional data would now be needed to establish the resource values within each unit. [12]

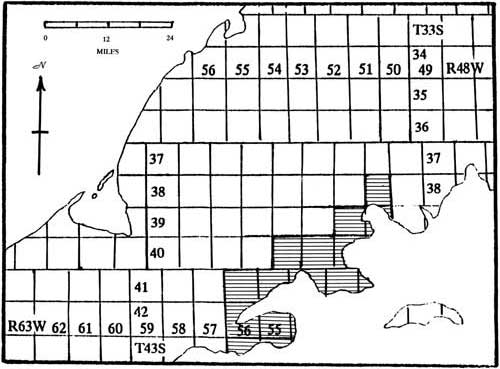

In June 1973, the task force issued a preliminary DES and master plan for the Aniakchak area. It was the first Aniakchak document the agency had released to the public. The plan called for a huge, 1.5 million acre Aniakchak Caldera National Recreation Area (see Map 14a). The acreage was twice as large as anything which the agency had proposed before. The plan was also remarkable in that it proposed a national recreation area--not a national monument--and the name of the area's major feature had been changed from a crater to a caldera. [13] The new boundaries extended along the Pacific Coast from Cape Kunmik to Chignik Bay, and along the Bristol Bay coastline from Cape Menshikof to the south end of Port Heiden. Even Meshik village was included. The task force justified the expanded boundaries because it wanted to include a representative sample of Alaska Peninsula ecosystems and because it hoped to include entire drainage basins whenever possible. The Bristol Bay lands were included in order to preserve significant caribou habitat; the Hook and Kujulik bays were included because they offered relatively high quality landing places. [14]

|

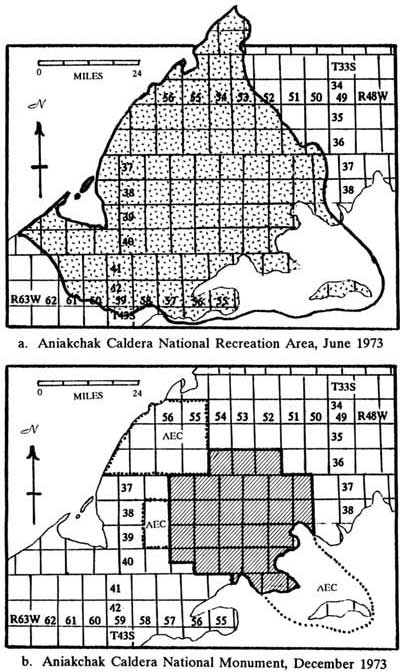

| Map 14. Aniakchak Administrative Proposals, 1973. (click image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The task force distributed the document to various governmental bodies, Native groups, and conservation organizations. Several of the report recipients--most probably the State of Alaska and various Native groups--protested the proposed plans. They pointed out that the area which was bounded by the caldera, the upper Cinder River drainage, Amber and Aniakchak bays, and the upper Meshik River drainage had been withdrawn as "d-2" land in 1972, and the only encumbrances on that land were the regional and village deficiency lands (noted above) which had been applied for by Native corporations. Outside the "d-2" lands, however, most of the land in the proposed park unit had been selected by the State of Alaska, by Meshik village, or by the Koniag Regional Corporation. Those state and the various Native groups took a dim view of being included in an NPS unit. Another difficulty in the plan was the existence of 115 mining claims on Cape Kumliun, at the south end of the proposed unit. [15]

Those protests were heeded by NPS officials. When the Alaska Planning Group, [16] in July 1973, presented its latest land use recommendations to the Assistant Secretary of the Interior, it called for only a 680,000-acre Aniakchak Caldera National Monument among the 49.1 million acres it suggested for national park units. The area recommended was less than half the size of the park unit which had been recommended a month earlier; it was slightly smaller than what Secretary Morton had decided upon in September 1972. The idea of a national recreation area was discarded, never to be brought up again. [17]

On December 18, 1973, just two years after ANCSA became law, Secretary Rogers C. B. Morton made his final recommendations to Congress. He recommended that 83.5 million acres be added to the national park, wildlife refuge, national forest, and wild and scenic river systems. Only 32.6 million acres, however, were recommended for NPS management, and he proposed a mere 580,000 acres for Aniakchak Caldera National Monument, far less than had been recommended in June. [18] (See Map 14b.) Gone was the middle Meshik River valley, Cape Kumliun, and the Weasel Mountain area. Several of the eliminated lands re-emerged as Areas of Environmental Concern (AECs). [19] The APG identified three such areas: 1) a 206,000-acre area northwest of the proposal, along the Bristol Bay coast, 2) an 82,000-acre area just west of Aniakchak Caldera, and 3) Sutwik Island, 46,000 acres in extent. The boundaries that remained in the monument itself were similar to those in today's monument and preserve. [20]

The 580,000-acre recommendation was a painful compromise, unacceptable to advocates in both the conservation and development communities. The National Parks and Conservation Association called the acreage "less than optimal" because it had been promulgating a 1.7 million acre proposal which would have included the Meshik and Cinder River watersheds, the Bristol Bay coast, and Cape Kumliun. The State of Alaska, on the other hand, recommended that a mere 138,000 acres be protected; it saw little need to protect anything but the caldera and the acreage immediately beyond. [21]

Interior Department Land Use Proposals

Before 1972, the National Park Service knew virtually nothing about the Aniakchak area. Some NPS staff may have been aware of the data Albright had collected relative to the proposed 1931 monument; beyond that, information was probably limited to that written by Father Hubbard and by U.S. Geological Survey personnel. Between March 1972 and June 1973, Alaska Task Force personnel were asked to supply sufficient resource information for a preliminary draft environmental statement and master plan; by December 1973, a DES and final master plan were due.

Planners, as they commenced their studies, knew that Aniakchak presented special problems. For example, the area was of particular interest to Native groups. ANCSA, the act which had started the "d-2" process, had granted 40 million acres of land (and almost $1 billion) to Alaska's Natives. Soon after ANCSA's passage, Koniag, Incorporated (a newly-established Native regional corporation) announced its intention to file for thousands of acres of so-called regional deficiency lands in the proposed park unit. In addition, the Afognak village corporation got ready to file for a large amount of village deficiency lands. Natives wanted full title over some of those lands; on other lands, it applied only for subsurface (i.e., mineral) rights. In addition, several individual Natives filed for land parcels in the area. In one category or another, Native corporations claimed most of the area within present-day Aniakchak National Preserve. [22]

Hunting was another concern altogether. The NPS did not normally allow hunting in national parks or monuments, and when the Alaska lands process began (after the passage of ANCSA) it fully anticipated that hunting would be similarly prohibited in the proposed parks of the forty-ninth state. But a roundabout series of events quickly derailed those assumptions.

The problem began in early 1972, shortly after the passage of ANCSA. The December 1971 act placed a 90-day freeze on much of Alaska's federal lands in order to give Federal agencies, as noted above, the opportunity to make preliminary land selections. In March 1972, at the end of the 90-day period designated by ANCSA, Interior Secretary Rogers C. B. Morton withdrew 80 million acres of Federal lands. But two months earlier, on January 21, the state had filed for 77 million acres of federal land; it did so in order to fulfill its obligations under the 1958 Statehood Act, which allowed the state to select 103 million acres of land for its own use. Not surprisingly, much of the land in the two selections overlapped; in fact, 42 million of the 80 million acres which Morton withdrew had been selected two months earlier by the state. Alaska's Attorney General, John Havelock, was so incensed at Secretary Morton's action that on April 10, he sued the Federal government in order to gain title to the state's full allotment. That lawsuit, Egan v. Morton, was settled on September 2 in an out-of-court agreement made without the consultation (and over the objections) of NPS officials. [23] In that agreement, the state agreed to drop its claim on the 42 million acres which had been claimed by both parties. In return, the Interior Department agreed to a series of provisions. One of those provisions opened 124,000 acres of land in the Aniakchak area--around Amber Bay, Cape Kumlik, and Aniakchak Bay--to sport hunting. [24] (See Map 15.)

It is not known why the Aniakchak area became the first Federal area that the state demanded to be opened to hunters. Outside sportsmen had been visiting the area for more than a decade in search of brown bear, moose, and caribou. Use, however, was not heavy, and several other Federal areas--the Lake Clark area or the Wrangell-St. Elias area, for instance--were more popular to the hunting fraternity.

The Alaska Task Force planners recognized that both the hunting areas, and the areas of interest to Native corporations, were located in areas close to the Pacific coastline. They also recognized that the area was being preserved because of two primary features: a dry caldera "where visitors can walk within a mountain," and "a river which can be followed from its origin within a mountain to its mouth at the sea." For each of those reasons, initial (September 1972) plans concentrated park development in the caldera and river area. The primary development and interpretive sites, therefore, were on the southwestern side of the caldera and on Surprise Lake within the caldera. There was also a proposed campground on the Aniakchak River; it was located just outside "The Gates," a gap in the caldera's eastern wall. Other proposed development sites were located on Meshik Lake and Hook Bay; the park headquarters, visitor center, and a campground were all to be located at Meshik village. In order to access the various sites, the agency planned three different transportation modes: floatplanes, tour boats, and all-terrain vehicles. By June 1973, development had been expanded to include campgrounds at the mouth of the Aniakchak River and on Sutwik Island. [25]

The June 1973 report had called for the establishment of a national recreation area surrounding Aniakchak Caldera. The designation at first seemed inappropriate because the area appeared to have such a low potential for recreational development. But a recreation area, not a national monument, was suggested for two reasons. First, sport hunting (because of the September 1972 agreement) had to be allowed in the coastal portion of the proposed unit; second, Koniag Incorporated was interested in mining some of the lands it had selected (and had a legal right to do so). A recreation area, therefore, was an appropriate designation for a park unit (such as this one) where a relatively broad range of land uses was allowed. Consistent with the recreation area designation, the NPS proposed to open all of Aniakchak area to mineral extraction, so long as it was "consistent with other values." It also proposed that hunting be allowed throughout the unit, except within the caldera itself. [26]

The December 1973 Draft Environmental Statement and Master Plan made several significant modifications to the earlier plans. Development plans were changed to eliminate the proposed facilities at Sutwik Island and Hook Bay (which were now located outside the proposed unit) and to add a foot trail which would parallel the entire length of the Aniakchak River. The surface transportation network proposed in June remained. All references to all-terrain vehicles, however, were eliminated; in its place, the report noted that "Surface corridors will be set aside after research determines the type of vehicle and corridor management which will not permanently damage the surface." [27] The land uses proposed in the December 1973 plan were more restrictive than the June plan had been, perhaps because a national monument--not a recreation area--was being proposed. Hunting was still allowed, but only on the coastal area which had been subject to the September 1972 agreement. Mining was also more restricted; the plan called for its prohibition except where Natives had selected subsurface rights. [28]

The December DES also indicated that the Aniakchak River had been nominated to the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. As noted in Chapter 5, Congress passed a law in 1968 which created such a system, and by February 1970 the Secretary of Agriculture and Secretary of the Interior had agreed on a series of supplemental criteria by which wild and scenic rivers would be established. The Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, which was assigned the task of evaluating Alaska's rivers, sponsored an interagency float trip down the Aniakchak River in July 1973. The state and federal personnel which participated in the river trip took three tumultuous days to float the 27-mile river. The group concluded that its scenic and recreational values were high and the commodity values of adjacent lands were low. They therefore urged the BOR to recommend that the entire river area, including the portion of it located inside the caldera, be classified as a so-called "wild" river. (Wild rivers were the most restrictive of three river categories in the system.) They further noted that if the river did not become part of the proposed monument, it should be protected as a separate entity in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. [29]

The issuance, in December 1973, of the Aniakchak DES and Master Plan documents signalled the beginning of a six-month public comment period. The documents were distributed to a wide variety of interest groups and individuals, many of whom responded with opinions and suggestions. The Alaska Planning Group digested those suggestions and in October 1974 issued its Final Environmental Statement. The report offered few major changes from those proposed the previous December. The development plan remained much as it had been before, and the degree to which mining and hunting would be allowed was similarly unchanged. [30]

NPS Keyman Activities

The October 1974 boundary and land use recommendations remained until 1977, when Congress began using them as a basis for legislation. During the interim, the NPS did what it could to gather new information about the proposed unit. Most of it was gained through the efforts of Ralph Root, the so-called "keyman" for Katmai and Aniakchak, who worked out of the Alaska Area Office from July 1975 through March 1977. (See Chapter 5.)

Root began his tenure by inspecting the two proposal areas. Then, after learning what the FES had planned for the area, he met with other task force personnel to set priorities for proposed studies. The FES had provided a multiplicity of purposes for the proposed monument, so Root and his colleagues simplified the situation. He noted that

Primary stress will be placed on the caldera, its flanks, and related geology, as well as on the entire Aniakchak River drainage system, and not on wildlife values. Research on volcanic features and mechanisms, as well as the study of plant succession in and around the caldera will be emphasized. [31]

In January 1976, he followed through on the results of that priority list by proposing a geological study of the monument, to include both an overview and a description of areas of special geological interest. By August, the study had been awarded to Dr. Robert Forbes of the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Geophysical Institute. Forbes soon learned, however, that the U.S. Geological Survey had recently completed a study in the area and that the agency was planning to conduct many of the same activities that were specified in his contract. He therefore deferred to the USGS and returned the contract award to the NPS. [32] The USGS, true to its word, completed the first of several agency-sponsored studies of Aniakchak caldera in 1977, and has continued to produce various technical papers on the area's geology. No geological overview of the Aniakchak area, however, was ever produced. [33]

Root also tried to stimulate other avenues of research, particularly into plant succession in the proposal area. In June 1976, he urged the funding of a biological survey of the monument; four months later, he noted that "a study of existing vegetational patterns and successional trends ... is necessary as baseline data upon which to measure future visitor impact on vegetation, especially in the caldera." [34] He also urged the completion of a cultural resource survey, and a peregrine falcon nesting and population survey. None of these studies, however, were undertaken during the post-ANCSA planning period. The only related study which shed light on the agency's research needs was a ADF&G-sponsored bear migration study which was conducted from 1970 through 1975. This study covered a 2800-square mile area, which included most of the proposed monument; the geographical focus of the study was Black Lake, over forty miles southwest of the caldera. [35]

Root, and the agency, had many other concerns to contend with during this period. Hunting, for example, was a high visibility problem. Some organized groups, such as the Alaska Department of Fish and Game and the Alaska Professional Hunters' Association, saw the September 1972 agreement between the state and federal government as an opening round victory. Based on that agreement, they fought to open the entire proposal area to hunting. Environmental groups, on the other hand, tried to ignore the agreement and demanded that hunting be prohibited throughout the proposal area. [36]

The NPS was caught in a quandary on the issue. The agency knew it had to allow hunting in the proposal area; it could not, however, decide how much hunting area to allow. In December 1975, Area Director G. Bryan Harry told a group of hunters that the area open to hunting might well extend beyond the parcels outlined in the September 1972 agreement; the only area which he insisted be closed was the caldera itself. [37] The agency continued, as it had since 1973, to propose that the entire proposal acreage be included within a national monument. But in March 1976, after much internal discussion, the NPS changed course and decided that the proposal area should be divided into a 340,000-acre national monument, where hunting would be prohibited, and a 240,000-acre national preserve, where hunting would be allowed. Two years before, the agency had created the first two national preserves--at Big Cypress in Florida and Big Thicket in Texas--in order to designate park units which allowed hunting. Aniakchak, it was proposed, would follow that model. That November, however, just three days after Jimmy Carter was elected president, the agency reverted back to its previous position and espoused a 580,000-acre national monument with "specified lands that would be zoned to permit sport hunting." [38]

Many of the difficulties regarding hunting in the Aniakchak area were based on a lack of data. The agency's only statistical source for harvest data was the harvest tags turned in by hunters. These data were gathered by game management unit. The various game management units were far larger than the proposed park unit; statistics on harvest data, therefore, were poor indicators of how much hunting took place in the Aniakchak area. [39] To learn more about area hunting patterns, the NPS agreed to sponsor a study of the monument's subsistence and sport hunting activities. That study was performed in 1975-77 by Merry Tuten, who worked under the auspices of the University of Alaska-Fairbanks Cooperative Park Studies Unit. Tuten's research concluded that the subsistence harvest was not sufficiently strong to demand hunting restrictions. She stressed, however, the preliminary nature of her research. She noted that the Alaska Fish and Game Department should be ready to reduce the amount of sport hunting allowed if the population of game animals fell. [40]

Finally, Root gained valuable information on area development plans by the various Native corporations. Bristol Bay Native Corporation, which had interests in the western end of the proposed park unit, and Koniag, Inc., which had interests in the central and eastern portions, had aggressive development plans for the area. A BBNC leader, for instance, urged that the NPS construct a permanent visitor shelter within the caldera (the agency had proposed only an unimproved interpretive site), and a Koniag official hoped that "some form of visitor services," presumably a lodge or other tourist node, would be established in the area. [41] Both corporations hoped to establish a wide variety of economic development projects on their lands, and the creation of an NPS unit in their midst promised to enhance visitor development possibilities. The regional corporations themselves, however, showed little interest in spurring that development.

Mining was the other activity which Native corporation officials hoped to develop. The U.S. Geological Survey and the state's Division of Geological and Geophysical Survey, in their various reports, had offered few indications of mineralization in the proposal area, and no known mining claims had been established within the proposed boundaries. [42] In 1975, however, a geochemical reconnaissance financed by Koniag Corporation located a porphyry-type copper deposit, with above normal amounts of copper, molybdenum, lead, zinc, and silver, in a two-mile-long band on Cape Kumlik. In 1976 the corporation announced that it was actively "pursuing the exploration of mineral values" in the area. The NPS knew that Koniag would develop the area if it was profitable to do so, and the agency made plans to respond to the development, either by allowing an access road into the area or by excising the eastern end of Cape Kumlik from the proposed monument. Testing, however, revealed that mineral values in the area were too low to support a commercial operation, and the corporation did not implement its development plans. [43]

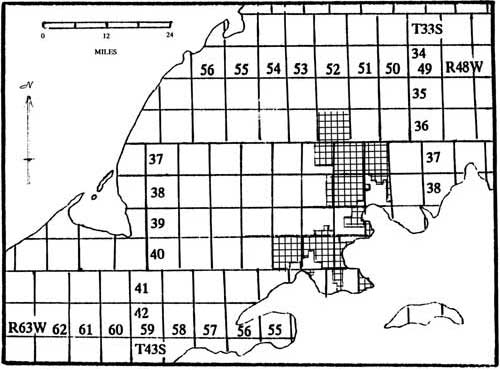

Koniag also eyed the area's possibilities for oil and gas development. The corporation had no immediate plans to drill in the area and filed no oil and gas leases, but wanted the right to be able to develop the area in the future. To foster that development, an amendment was passed to ANCSA on January 2, 1976 (see Map 16) which gave the corporation subsurface rights to oil and gas in the eastern half of the proposal area. [44]

|

| Map 16. Areas in Which Subsurface Rights Were Provided to Koniag, Inc. by ANCSA Amendments of January 2, 1976 (P.L. 94-204, Section 15 (a)). (click image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Scattered oil and gas exploration activities, in fact, took place in the proposal area. During the summer of 1975, Root discovered that a geophysical seismic crew had been active along Northeast Creek, north of Amber Bay. A crew was also active at Yantarni Bay, east of the proposal boundary. A year later, a helicopter-based oil-company crew planned an extensive exploration in the proposal area. [45]

The NPS put substantial effort into planning for visitation into the area. As noted above, it had assembled and refined a series of development plans as part of the October 1974 Final Environmental Statement. During the ensuing years, those plans were modified as staff gained new knowledge about the area. In the FES, development sites had included the headquarters and allied facilities (at Meshik village), a developed campground (at Meshik Lake), two primitive campgrounds (just east of the caldera and at the mouth of Aniakchak River), and two interpretive sites (on the southwestern rim of the caldera and at Surprise Lake). Plans called for Meshik village, the caldera rim, and Meshik Lake to be connected by a multipassenger surface transportation; the nature of the transport system, however, had not been decided upon. This plan remained intact until November 1976. [46] A month later, however, new NPS plans emerged which called for the construction of 16' x 20' Panabode-style backcountry shelters at Meshik Lake, previously a developed campground site; Surprise Lake, previously an interpretive site; and a newly-designated site along Lava Creek, at the north end of the proposed unit. NPS staff also modified the proposed transportation system to eliminate any references to specific routes. [47]

Although NPS officials created relatively sophisticated visitor development plans, they had few illusions that the creation of a new park unit would result in significant new visitation. An agency-sponsored study indicated that "Use of planned facilities is expected to remain well below capacity for many years." The agency predicted that annual visitation in 1980 would remain below 500; by 1985, fewer than 1,000 people would be visiting the park unit each year. Half of those visitors were expected to be local residents; many of the remainder would be sport hunters. [48]

The monument, it appeared, would be of little interest to non-hunting recreationalists. Few were known to have visited the area since Hubbard's expeditions in the 1930s, and only one was known to publicize his visit. That visitor was Ben Guild, an Eagle River resident. Guild, a mycologist and former hunting guide, spent six weeks in the caldera in 1973, living in a tent. He returned there in 1976, constructed a stout 10 x 12 tent cabin and lived in it for a month. Guild loved the caldera; to show others its beauties, he took photographs, shot extensive movie footage, and wrote a book on the area's vegetation. Local residents thought him odd; they called him the "Wild Man of Aniakchak." The NPS, however, was thankful for his contributions. Staff took advantage of his accommodations as well as his knowledge of the area; Guild cooperated with them because the NPS, in his opinion, was the agency best qualified to manage the area. [49]

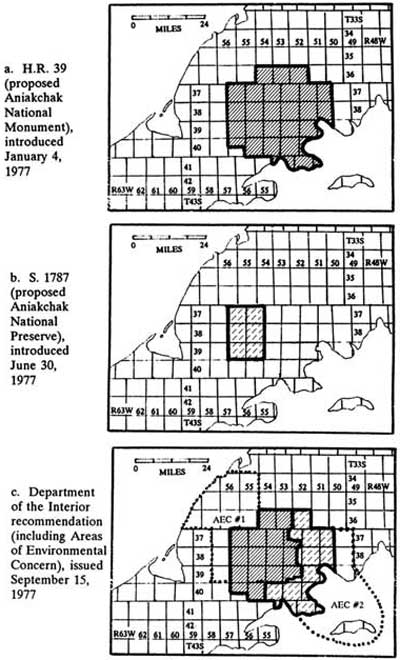

Congress Establishes the Monument and Preserve

In November 1976, Democratic candidate Jimmy Carter defeated Republican Gerald Ford for the presidency, and the following January, Congress began its consideration of an Alaska lands bill. On January 4, environmentalists weighed in with their version of the bill when Rep. Morris Udall introduced H.R. 39 (see Map 17a). That bill, among its other provisions, called for the creation of a 580,000-acre Aniakchak National Monument, the same size which had been called for in the Secretary of the Interior's proposal in December 1973. [50] Udall's bill, which was intended as an opening gambit and not as a final legislative vehicle, prohibited sport hunting throughout the monument and did not address the oil and gas extraction rights which had been included in the 1976 ANCSA amendment. [51]

|

| Map 17. Aniakchak Proposals, 1977. (click image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Those who hoped to minimize the Park Service's role in the state found the acreage in Udall's bill excessive. Two years before, the State of Alaska and the Joint Federal-State Land Use Planning Commission had made their own recommendations. The state had recommended a 138,000 acre preserve--just a rectangle which included the caldera and its flanks--where sport hunting would be allowed. The JSFLUPC, only slightly more protective, recommended a 183,000 acre monument (sport hunting would be prohibited) plus a broad, east-west corridor for an Aniakchak Wild and Scenic River. [52] Those recommendations were incorporated into S. 1787, a so-called "consensus bill" which was introduced by Senator Ted Stevens on June 30, 1977. This bill (see Map 17b) called for the creation of a 180,000 acre Aniakchak Caldera National Preserve. [53]

While Congress was holding public hearings on H.R. 39, the Interior Department was making its own study of the various proposals. Cecil Andrus, Carter's Secretary of the Interior, let it be known that he would re-evaluate the previous proposals, noting that the new administration would not be bound by recommendations "the staff had made in years gone by." Instead of following the model set by former Secretary Morton, he based his recommendations on those included within Rep. Udall's H.R. 39. [54] He asked the NPS (and the other Interior Department agencies) to prepare revised acreage recommendations. Given the broad expertise which the various keymen had gained over the past two years, NPS Director William J. Whalen felt comfortable in recommending 50.9 million new acres to the system. Regarding Aniakchak, he proposed a 345,000-acre national monument and a 212,000-acre national preserve. [55]

Andrus compared the NPS recommendations with those of the other Interior agencies, and on September 15 issued the Carter administration's legislative recommendations. They called for the addition of 41.8 million acres to the NPS system. The proposal (see Map 17c) called for a 364,000-acre Aniakchak National Monument and a 249,000-acre Aniakchak National Preserve. In his testimony before a Congressional subcommittee, he stated that his Aniakchak proposal had been endorsed by both the State and the Native corporations. It was slightly larger than Secretary Morton's had been, the boundaries having been changed, where possible, to follow topographic features rather than township and section lines. Andrus also noted that

This is basically the same proposal made in 1973 as it relates to land use, however, the preserve classification is now used for the coastal portions ... in accordance with traditional classification to allow hunting and oil and gas.

Andrus proposed no "instant" wilderness at Aniakchak for either the monument or preserve. He did, however, include a provision that both units would be studied for wilderness designation within seven years after the units were established. [56]

As noted in Chapter 5, the House of Representatives passed an Alaska Lands bill during the 95th Congress. Passage of a modified version of H.R. 39 took place on May 19, 1978; included in the bill was a provision for a 350,000-acre monument and 160,000-acre preserve for Aniakchak. The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, on October 5, sent the bill to the full Senate. That bill was so unsupportive of other park areas that conservationists referred to it as a "rocks and ice" proposal; at Aniakchak, however, it called for a generous 510,000-acre monument and a 140,000-acre preserve. The Senate adjourned without having passed either the Energy Committee's bill or any other Alaska lands measure. [57]

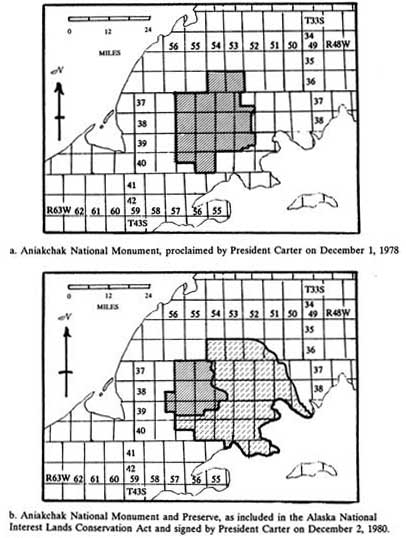

The administration knew that ANCSA called for the disposition of the Alaska lands issue by December 18, 1978. Because Congress failed to act on the matter, Secretary Andrus recommended that President Carter invoke the Antiquities Act and designate much of the acreage under consideration within national monuments. On December 1, Carter followed up on Andrus's recommendations and, in a series of presidential proclamations, created 15 new and two expanded monuments, covering a total of 56 million acres. Proclamation 4612 created the 350,000-acre Aniakchak National Monument (see Map 18a). At the urging of Secretary Andrus, Carter also withdrew the area between the monument and the coast so that the next Congress could consider its potential as parkland. [58]

|

| Map 18. Aniakchak Boundaries, 1978-80. (click image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Many Alaskans were angry at what they perceived as the high handed tactics Andrus and Carter had used in "locking up" the various national monuments. Many, however, felt that the monuments would be temporary until a Congressional solution to the Alaska lands question could be found. On January 15, 1979, at the beginning of the 96th Congress, Rep. Morris Udall reintroduced H.R. 39, a "refinement" of the bill which had passed the House the previous year. Udall found the passage of a bill rougher than the previous year; even so, he and Rep. John Anderson (R-IL) were able to push a compromise bill, H.R. 3651, through to a House vote. The Udall-Anderson bill, renumbered H.R. 39 at the last minute, passed the House on May 16, 1979. The bill called for the creation, at Aniakchak, of a 350,000-acre monument and a 160,000-acre preserve. [59]

H.R. 39 was referred to the Senate Energy Committee on May 24. The committee, however, was in no hurry to proceed, and did not begin its work until October 9. Using Sen. Henry M. Jackson's S. 9 as a vehicle for markup, the bill moved sporadically until early 1980. The committee then put off consideration of the bill until July. Environmentalists and Interior Department officials began to worry that the Senate would refuse to confront the Alaska lands question again. In February 1980, to prod the Senate into activity, Secretary Andrus withdrew 36.9 million acres as wildlife refuges and an additional 3.2 million acres of "natural resource areas" adjacent to recently-designated national monuments. One of the four "natural resource area" withdrawals was a 160,000-acre reservation at Aniakchak. [60]

In late July, the Energy Committee resumed its markup of the Alaska lands bill. The bill, which was heavily influenced by senators Jackson and Stevens, finally emerged from the committee in mid-August, and on August 18 the full Senate passed Amendment No. 1961, a substitute for Sen. Jackson's Energy Committee bill. Amendment No. 1961 called for the inclusion of just 137,000 acres in Aniakchak National Monument. In addition, it proposed a 466,000-acre Aniakchak National Preserve. [61]

Senate leaders adamantly proclaimed that they would not budge from the bill they had passed. The House, however, was hopeful that a compromise could be reached between the two bills. Largely because of the dilatory tactics of Sen. Stevens, the two bodies were unable to reach a compromise, and they were forced to delay their efforts until after the 1980 election. The sweeping Republican victory that year, however, forced Rep. Udall to back down and agree to the Senate's version of the bill. On December 2, 1980, President Carter signed the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act (Public Law 96-487) into law. [62] The act created a 602,779-acre Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve (see Map 18b). Within that preserve, it designated the 32-mile Aniakchak River and its 31 miles of tributaries as wild rivers (according to definitions in the National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act). None of the acreage in the monument or preserve was designated as wilderness. Congress did, however, mandate that the area be studied for its wilderness potential with five years of the act's passage. [63]

The acreage included in the Aniakchak unit was substantially smaller than the 1.5 million acres that had been proposed, in June 1973, as an Aniakchak Caldera National Recreation Area. It was dramatically larger, however, than the acreage which NPS officials had called for in early 1972. Exploration of the area by agency staff helped identify the most significant areas to protect, and because there were few major land-use conflicts in the area, the area which had been set aside in December 1973 was similar to that which was included in the Alaska Lands Act. The only major point of dispute during the seven-year period that led up to ANILCA was the number of acres in which hunting would be allowed. Viewed in comparison with the acreages included in various Interior Department plans and the two House-passed bills, the existing monument and preserve appears to have been advantageous to sport hunters, miners, and other consumptive user groups.

The Alaska Lands Act gave a far broader purpose for establishing the unit than the Final Environmental Statement of October 1974 had provided. Section 201(1) of the act declared that the unit would be managed

To maintain the caldera and its associated features and landscape, including the Aniakchak River and other lakes and streams, in their natural state; to study, interpret, and assure continuation of the natural processes of biological succession; to protect habitat for, and populations of, fish and wildlife, including, but not limited to, brown/grizzly bears, moose, caribou, sea lions, seals, and other marine mammals, geese, swans, and other waterfowl and in a manner consistent with the foregoing, to interpret geological and biological processes for visitors.

The act also provided that "Subsistence uses by local residents shall be permitted in the monument [and preserve] where such uses are traditional...." Subsistence uses were permitted in all of the newly-created preserve areas; it was also allowed in most of the new park and monument areas. As Merry Tuten had shown in her 1977 report, subsistence was a major land use in the area, and the new law allowed for its continuation. As was noted in Chapter 5, however, this provision for subsistence use had not been extended to Katmai National Park lands. [64]

The Aniakchak area, at long last, had been given Congressional protection. It was now time for the National Park Service to manage the area so that its purposes, at outlined above, could be realized. A large amount of work would need to be accomplished in pursuit of those goals.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap14.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2000