|

KATMAI / ANIAKCHAK

Isolated Paradise: An Administrative History of the Katmai and Aniakchak National Park Units |

|

| PART II: ANIAKCHAK NATIONAL MONUMENT AND PRESERVE |

Chapter 15:

Management of Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve

Initial Planning Efforts

Aniakchak National Monument, covering approximately 350,000 acres, was proclaimed by President Jimmy Carter on December 1, 1978. As noted in Chapter 14, Carter did not intend that his action would be permanent, and many hoped that the 96th Congress, which would meet in 1979 and 1980, would complete what the 95th Congress had failed to do in 1978.

In the meantime, the National Park Service assumed authority over a large expanse of new acreage. The agency had no management plan for Aniakchak or any of the other new NPS units, so on December 26, interim management guidelines were issued for the newly-created parklands. The guidelines recognized that the Bureau of Land Management (which had previously administered the lands) assumed primary responsibility for interim management, and were predicated on the assumption that they would be in effect for only a short time. On June 28, 1979, the NPS issued proposed general management regulations for the new parklands. Those regulations, however, were never adopted. [1]

The period between December 1978 and December 1980, regarding many of the new Alaska monuments, was marked by rancor and conflict. Disputes erupted between the BLM and the NPS over interim management strategy, and communities near several of the new units loudly protested the presence of the new monuments. The NPS tried to protect the new areas by reprogramming existing funds that would have brought new staff into the area. That request, however, was denied. Faced with the prospect of having no protection over the monuments, the agency reacted by creating the so-called Ranger Task Force. The ad hoc group was composed of senior level rangers on temporary duty from various Lower 48 assignments.

Little if any conflict took place at Aniakchak. The Congressional deliberations of the 95th Congress had brought forth few resource conflicts over the area, and as consequence, few complained when the area was proclaimed a national monument. Local residents appear to have been supportive of Carter's proclamation, and so far as is known, no one from the Ranger Task Force had need to visit the area. Use of monument land during 1979 and 1980 continued much as it had in previous years. [2]

The passage of the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, which created Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, had little immediate effect on the area. The area acquired its own budget--$61,400 for the 1981 fiscal year. No moves, however, were made to establish an independent administrative presence. Following an ad hoc, incremental philosophy, the agency decided, for the time being, to direct the unit from Katmai National Park and Preserve's offices in King Salmon, and Dave Morris became the superintendent of both the Katmai and the Aniakchak NPS units. Despite the plans which had been laid out during the mid-1970s, there was no attempt to establish a headquarters facility at Meshik village (Port Heiden). No construction was attempted within Aniakchak's boundaries, either. The agency recognized that there was little need for an active management presence. No NPS personnel, in fact, visited Aniakchak for more than one and a half years after President Carter signed ANILCA into law.

NPS management began to express an interest in the unit in 1982. Two brief visits were made that summer. The following May, Superintendent Morris helped complete a Statement for Management which provided a list projects that the agency needed to complete in the fields of administration, natural resources, cultural resources, and visitor use and interpretation. The list was unrealistically long--too long to be completed in the short term--but it provided a basis for future park efforts. [3]

General Management, Land Protection, and Wilderness Plans

Section 1301 of the Alaska Lands Act stated that a "conservation and management plan" had to be developed and transmitted "to the appropriate Committees of the Congress" by December 1985. Given such a deadline, the so-called Aniakchak Planning Team--consisting of the Katmai/Aniakchak superintendent, regional office staff, and planners from the Denver Service Center--was organized to compile a general management plan, a land protection plan, and a wilderness suitability review. Concentrated planning efforts began in the summer of 1983. An aerial survey took place. More important, the two-ranger team of George Stroud and Lynn Fuller spent two months living in the old Columbia River Packers Association bunkhouse (locally known as the Alaska Packers Association cabin) at the mouth of the Aniakchak River. Stroud and Fuller made a reconnaissance of the Pacific coastline, conducted an informal biological survey, and made their presence known to passing fishers and other area visitors. As a highlight of their summer, Stroud and Fuller joined a three-man planning team as they explored the caldera and rafted down the Aniakchak River. [4]

In February 1984, the team distributed an "Issues and Management Alternatives" booklet for public review. The report requested public comment on how the unit should be managed and suggested three management scenarios. Alternative A called for a continuation of existing, minimal style of management, where the agency would play a passive, reactionary role. Alternative B called for the continuation of existing land uses but an increasing level of resource management and protection. The alternative called for the construction of a patrol shelter at Meshik Lake, a seasonal ranger station at Port Heiden, and the improvement of the CRPA cabin at the mouth of the Aniakchak River. Alternative C called for an even higher level of both use and resource management. It called for a patrol shelter at Meshik Lake; visitor use shelters in the caldera; a visitor use shelter at the mouth of the Aniakchak River as well as improvements to the CRPA cabin; the construction, in Port Heiden, of both an area manager's office and a visitor information station; and the implementation of a surface transportation system connecting Port Heiden with the caldera rim and other points of interest. [5]

The alternatives were then presented for informal public review. That June, rangers Stroud and Fuller returned to the CRPA cabin and continued their work of the year before. Meanwhile, the planning team began compiling the a draft version of the general management plan, land protection plan, and wilderness suitability review. They had decided on a preferred alternative by the end of 1984; the draft document was issued in February 1985. [6]

The draft GMP recognized that the underlying management emphasis was to "better understand its natural and cultural resources and to ensure that natural ecological processes and cultural resources are preserved through monitoring and protection activities." In order to fulfill that philosophy, the draft plan offered elements from both Alternative A and Alternative B as well as a few elements that had existed in none of the three alternatives. According to the plan, no new facilities were to be established, either at Port Heiden or inside of the monument and preserve. The only proposed improvements would be the restoration of the so-called public use cabin (CRPA cabin) at the mouth of the Aniakchak River and the laying out of an identified hiking corridor between Meshik village and the caldera rim. The plan called for the placement of a part-time coordinator in Port Heiden and Chignik Bay village (but no NPS facilities), and several parts of the unit would be subject to periodic NPS management activities. Staffing for the unit would consist of a year-round resource management specialist and two seasonal rangers. [7]

The land protection plan, issued at the same time as the GMP, noted that only 12,507 acres--just two percent of the monument and preserve--were owned by nonfederal entities. (The State of Alaska had jurisdiction over three parcels totalling 7,577 acres, and the Port Lions Village Corporation had gained interim conveyance to a 4,930-acre tract.) But another 206,444 acres in the preserve--some 44 percent of the preserve--had been claimed or selected, either by Native corporations or Native individuals. The eight different tracts were primarily located in two large blocks, at the eastern and southern end of the preserve, respectively; together, the various tracts included most of the preserve's coastline. The largest claim, noted in Chapter 14, was the 152,780-acre parcel selected by the Koniag Regional Corporation for in-lieu oil and gas rights.

Neither the eight selected tracts, nor any of the four nonfederal tracts, appeared to be in imminent danger of development. The National Park Service, therefore, assembled a priority list for them in the order of their perceived value to the agency. It was most interested in acquiring Native claims located on the shores of Surprise Lake and Meshik Lake, because construction of improvements on those parcels would be contrary to park goals as expressed in the draft GMP. For the same reasons, the agency was next interested in acquiring title to three tracts which abutted Aniakchak and Amber bays. As called for in the plan, the NPS outlined six purchasing priorities which included all twelve of the parcels which were not owned by the federal government. The agency was quick to point out, however, that no funds had been authorized, appropriated, or obligated for such purchases. [8]

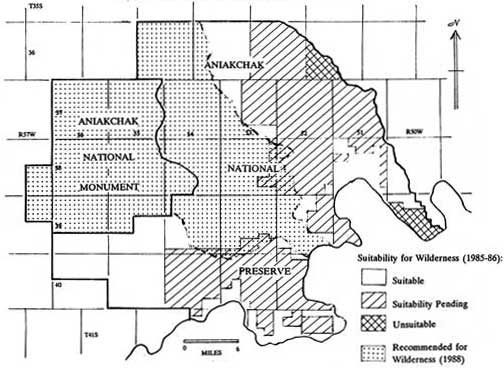

The wilderness suitability review, which was also part of the GMP package, revealed that the entire monument and preserve was a de facto wilderness. The NPS, however, was in no position to recommend wilderness on lands over which it did not have full jurisdiction. The review, therefore, concluded that the 383,887 acres under unencumbered federal jurisdiction (64 percent of the monument and preserve) were considered suitable for wilderness (see Map 19). The 206,444 acres which had been selected by Native corporations or individuals were given a "suitability pending" designation, and the 12,507 acres which were in nonfederal ownership were unsuitable as wilderness. [9]

|

| Map 19. Aniakchak Wilderness Recommendation (1985-88). (click image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Soon after the draft plan was issued, in late April and early May 1985, public meetings were held in King Salmon, Naknek, Anchorage, and other local communities. [10] The public was given four months to comment on the draft plan, and the plan was modified to accommodate many individual concerns. The general level of development recommended in the draft GMP, however, remained just as it had before. The land protection plan was also the same as before, except that three tracts--two selected properties and an interim conveyance--had recently become unencumbered federal land. The two selected properties had been Priority 2 land parcels in the draft land management plan. Because these two parcels were no longer a problem to NPS land managers, the large in-lieu oil and gas tract became a priority 2 parcel. The wilderness suitability review was also similar to what had been called for in the draft plan. The only changes were that the parcels which had recently become unencumbered federal land were now "suitable" instead of being in the "suitability pending" category. The final plan declared that 404,962 acres (67 percent of the unit) was suitable for wilderness, 185,310 acres had "suitability pending," and 12,507 acres were unsuitable for wilderness designation. The three plans were signed by Superintendent David Morris and Regional Director Boyd Evison in June 1986, by NPS Director William Mott in October 1986, and by Assistant Secretary of the Interior William Horn in November 1986. [11]

Wilderness Recommendations

As thorough as their efforts had been thus far, NPS planners had one more task to complete in order to satisfy the ANILCA mandates. As noted above, Section 1317 of the act had required the completion of a wilderness suitability review for each new park unit by December 1985. The same section, however, required that by December 1987 the President "shall advise the Congress of his recommendations with respect to such areas." In order to provide the information on which such a recommendation could be based, agency planners began preparing a series of draft environmental impact statements. Work began in March 1986. Beginning in September, the first in a series of wilderness meetings was held around the state; one of those meetings was held in King Salmon on October 16, 1986 to discuss wilderness designation at Aniakchak. Preparation of the Aniakchak EIS followed.

In spite of the Congressional deadline, the draft EIS was not able to be completed until May 1988. The document offered four wilderness alternatives. Alternative 1, a no-action plan, recommended no wilderness. Alternative 2 offered 293,336 acres of wilderness, or 49 percent of the combined park and preserve. Alternative 3 offered 451,916 acres of wilderness, or 75 percent of the NPS unit. Alternative 4 recommended wilderness throughout the area. [12]

The public comment period for the report began in mid-May, and in July two public hearings were held, one in Arlington, Virginia, the other in Anchorage. A public meeting was also held in King Salmon. The public was given until August 29 to comment. Well over one hundred people expressed written or oral comments on the draft plan. Based on those comments, the NPS created a final EIS. They did so quickly, because Congress required that the document be completed by September 30.

After mulling over its options, NPS planners chose Alternative 2. This alternative, which recommended wilderness designation for the entire monument, the Aniakchak River system, and the western side of the Cinder River drainage, was selected because it included the most valuable features in the unit and the federal lands which surrounded them (see Map 19). Alternatives 3 and 4 were avoided because they impinged on existing hunting camp operations and because they conflicted with lands which had been selected by Native corporations or patented by the State of Alaska. [13]

Congress has not yet acted on the EIS, and Aniakchak still contains no designated wilderness. Whether wilderness will be created in the near future depends, in part, on the success of recent legislation which would allow the Koniag Regional Corporation to sell its extensive in-lieu oil and gas acreage to the Federal government. (See section below.) In October 1990, Rep. Don Young (R-AK) introduced the Alaska Peninsula Wilderness Designation Act of 1990 (H.R. 5956) which would have designated as wilderness the entire 602,779-acre unit in addition to providing for the sale of the in-lieu acreage. The bill was submitted in the waning hours of the 101st Congress--too late for it to be considered in committee. A similar bill, H.R. 1219, was introduced in March 1991 and fared better than its predecessor. The bill passed the House on August 3, 1992. The bill was then referred to the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. The upper chamber, however, did not hold hearings on it and no further action was taken in the 102nd Congress. [14] In April 1993, similar bills (H.R. 1688 and S.B. 855) were introduced which would have also allowed the sale of Koniag subsurface rights. The House bill contained language which created wilderness for the entire monument and preserve; the Senate bill, however, contained no such language. Those bills were opposed by the Clinton administration; perhaps because of that opposition, neither bill emerged from its respective committee. [15]

Subsistence Management

As noted above, Section 201(1) of the Alaska Lands Act declared that Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve would be open to subsistence uses. In order to regulate subsistence, the act declared that by December 1981, a series of regional advisory councils and local advisory committees would be established for the state's public lands. It also required the appointment of a series of National Park Service advisory commissions. Section 808 noted that

the Secretary [of the Interior] and the Governor shall each appoint three members to a subsistence resources commission for each national park or park monument within which subsistence uses are permitted by this Act. The regional advisory council ... shall appoint three members to the commission each of whom is a member of either the regional advisory council or a local advisory committee within the region and also engages in subsistence uses within the park or park monument. Within eighteen months from the date of enactment of this Act, each commission shall devise and recommend to the Secretary and the Governor a program for subsistence hunting within the park or park monument.... Each year thereafter, the commission ... shall make recommendations ... for any changes in the program or its implementation which the commission deems necessary. [16]

Events proved that creating the Aniakchak National Monument Subsistence Resource Commission would be far easier than fulfilling its Congressional mandate. The nine member commission was not able to meet until April 18, 1984. That meeting, however, attracted only four members, which did not constitute a quorum. Meeting dates set for later that year were repeatedly delayed. The following March, a five-member quorum met in King Salmon and adopted its first resolution. The resolution, which consisted of four separate recommendations, was intended "to assure that present and future local residents adjacent to the monument retain accessibility to the subsistence resources of the monument."

Interest in the commission waned over the next few years. During the six-year period following the March 1985 meeting, the commission met only thrice: in 1986 and 1987, both of which were held at King Salmon, and once in 1990 at Port Heiden. A quorum could not be mustered for any of the three meetings. The primary business of those meetings was the creation of a subsistence hunting plan. Initial recommendations were formulated at the 1986 meeting, and in 1987, a final recommendation was passed which was forwarded to the Governor and the Secretary of the Interior. A central tenet of that resolution was the Monument's subsistence uses "be limited to those persons who had their primary place of residency within the local region on December 2, 1980, members or their immediate families, and their direct decedents who continue to reside in the local region." [17] Two of the five recommendations which were passed in 1985 and 1987 were accepted by the Secretary of the Interior; the other three were not acted upon.

The agency's appointment, in 1991, of a Subsistence Specialist for the Katmai and Aniakchak units signalled a renewed interest in subsistence issues. In order to revise the subsistence recommendations made in 1985 and 1987, the NPS organized two meetings of the Aniakchak National Monument Subsistence Resource Commission in 1992: in March at Port Heiden and in November at King Salmon. As a result of the two meetings, both of which fostered a quorum, the commission passed six draft recommendations. Those recommendations have not yet been finalized. [18]

Visitor Use

Because of its remoteness, Aniakchak has had one of the lowest annual visitor totals of any unit of the National Park Service system. When the agency gained jurisdiction over the unit, few had an inkling of how much visitation existed. NPS planners knew that a smattering of subsistence users and sport hunters used the park. But the area attracted only a handful of non-hunting recreationalists; as a 1983 document admitted, "There is not a tradition of conventional visitor use of the area. Indeed, fewer than ten visitors per year are known to enter the area for the purpose of viewing its major geologic features." [19]

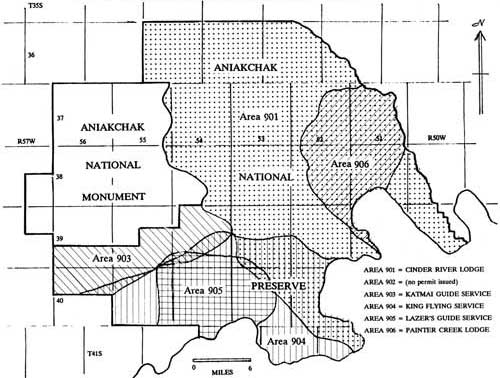

Merry Tuten's 1977 study had provided an overview of subsistence usage in the area. Beyond that, one of the only ways to estimate the number of park visitors, at least in the early years, was to analyze hunting guide areas. Tuten had indicated that between 1973 and 1976, thirteen hunting guides had maintained at least one camp within the boundaries of the present monument and preserve. Since the passage of ANILCA, however, only eight hunting guides have conducted commercial hunts within six state-designated guide areas (see Map 20). (In one of the guide areas, a son took over from his father; in another area, one partner purchased the interests of another.) Knowing the number of active hunting areas provided a rough estimate of the number of sport hunters to visit the area.

|

| Map 20. Hunting Guide Areas in Aniakchak National Preserve, 1988. (click image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Commercial use licenses, or CULs, provided another method for estimating the number of visitors. Because the area was so remote, almost all recreational visitors to the monument and preserve came by commercial conveyances. Beginning in 1980, the NPS began issuing commercial licenses as a way to regulate the activities of air taxi operators, fishing and hunting guide services, and other companies who intended to use the various park units on a temporary basis. (In 1981, the licenses were renamed commercial use licenses.) By the mid-1980s, most of the companies who took visitors to and from Aniakchak had obtained CULs from the NPS. CUL holders were required to pay the NPS a nominal annual fee. At first, they were not obligated to tell the agency how many of their patrons visited the various park units. As time went on, however, the agency became increasingly insistent that commercial operators complete a so-called activity summary of trips made to the various parks.

Data obtained from the various commercial use licenses indicates that few non-hunters visited Aniakchak for recreational purposes in the early to mid-1980s, and park staff estimate that fewer than 20 visitors per year came for recreational purposes during this period. Most who did make the trek out to Aniakchak did so in hopes of taking a float trip down the Aniakchak River. From 1981 through 1987, the number of non-hunting CUL holders--that is, the number of companies who hoped to conduct non-hunting trips to Aniakchak--rose from 3 to 9 (see Table 1). During that period, however, no more than two non-hunting companies were known to take visitors to Aniakchak in any given year. In the late 1980s and early 1990s more companies became interested in the budding tourist trade. The number of non-hunting CULs rose from 13 in 1988 to 20 in 1992; at the same time, the number of companies known to actually carry visitors to Aniakchak varied between 3 and 7. Throughout this period, between four and six hunting-guide operations were active in the NPS unit.

Table 1. Commercial Use License Activity in Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, 1981-1993

| Non-Hunting: | Hunting: | |||

| Year | CUL Holder | Act. Summ. | CUL Holder | Act. Summ. |

| 1981 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1982 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 1983 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| 1984 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| 1985 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 1986 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| 1987 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| 1988 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| 1989 | 13 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| 1990 | 16 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| 1991 | 20 | 7 | 5 | 5 |

| 1992 | 20 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| 1993 | 14 | unk. | 4 | unk. |

Source: Commercial Use License files, AKSO-EC files. For equivalent

statistics for Katmai, see Norris, Tourism in Katmai Country,

143-45. | ||||

Because visitor numbers were so low, the NPS made no attempt to tabulate them prior to 1989. [20] That year, however, visitation was significantly augmented by personnel brought in to fight the Exxon Valdez oil spill.

The spill, as described in Chapter 6, took place shortly after midnight on March 24. The Aniakchak area, located almost 500 miles southwest of Bligh Reef, seemed an unlikely recipient of Exxon Valdez oil. But by the end of March oil had begun seeping out of Prince William Sound, and NPS personnel recognized that prevailing currents would ultimately bring it to the shores of Katmai and Aniakchak. To command the threat, the agency launched a three-pronged strategy. First, it brought a team of experts north from Olympic National Park in Washington to assess the preserve's 68 miles of beaches prior to oiling. This team, led by Douglas Houston, left the Homer Incident Command Team center for Aniakchak on the M/V Polar Star on April 19 and returned on April 29. [21] The second aspect of the strategy was the clean-up itself. Oil began washing up on Aniakchak's beaches on July 2, and in mid-July cleanup crews were in full swing mopping up oil and debris. Crews that summer canvassed slightly over half the length of Aniakchak's coastline. (About one-third of the Aniakchak coast was never oiled). The amount of waste collected, however, was small. Cleanup crews at Katmai, for instance, collected over 95,000 bags of spoil. At Aniakchak, however, only 154 bags of spoil were collected. [22] The final way the NPS dealt with the oil spill was by conducting a post-oiling assessment, which was done in August. The team from Olympic National Park undertook this responsibility, along with two biotechnicians who worked out of the CRPA cabin. Forty beach assessments were made along the Aniakchak coastline. [23]

Oil cleanup and assessment operations continued in 1990, though at a reduced scale from that of the year before. Aniakchak, which had been only lightly oiled, was not visited by Exxon-funded oil cleanup crews. Instead, the NPS decided to contract with the City of Chignik, 50 miles to the southwest, for cleanup. The agency issued the city a special use permit, and crews were paid through a funding program implemented by the State of Alaska. The NPS, however, contributed much of the support cost. [24]

The result of all this activity was the arrival of hundreds of people to Aniakchak who had little interest in recreation. As noted in Table 2, a total of 1318 people visited the area in 1989, but only 853 recreational visits took place. Therefore, perhaps 450 or more agency personnel and cleanup crew members came to Aniakchak because of the oil spill. In 1990, perhaps 50 such visits took place.

Available statistics (see Table 2) suggest that recreational visitation to Aniakchak has grown significantly in recent years. Since 1989 (the first year in which figures are available) the number of recreational visits has risen, on the average, 25 percent each year. In 1992, an estimated visitation of 1638 was tallied. [25]

Table 2. Visitation to Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve, 1989-1992

| Year | Total Visits |

Recreational Visits |

Overnight Visits |

| 1989 | 1318 | 853 | 917 |

| 1990 | 1018 | 966 | 1201 |

| 1991 | 1478 | 1469 | 913 |

| 1992 | 1646 | 1638 | 1034 |

Source: NPS, "Summary of Obligations and Program Evaluation,

Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve," AKSO-EEI files. | |||

Perhaps as the result of that growth, interpretive information has become increasingly available in recent years. In 1986 David Manski, the Resource Management Specialist assigned to Aniakchak issues, wrote the unit's first site bulletin. In the late 1980s, an interagency interpretive kiosk in King Salmon, with a section reserved for Aniakchak, was installed. The Katmai visitor newsletter, which debuted in 1990, likewise contained information on Aniakchak. In 1992, an Aniakchak visitor information folder was produced, and an NPS-sponsored Katmai book, which also discussed Aniakchak, was completed. [26]

NPS Personnel Establish a Presence

Soon after the unit was created, NPS staff in King Salmon recognized that they needed to establish a presence in order to become familiar with local resources and to let local residents know of their presence. In the spring of 1982, Superintendent Morris hired a seasonal ranger who would concentrate on Aniakchak affairs. The summer, however, did not go as planned. As Morris noted in his annual report,

Marc Matsil was hired to be "the" Aniakchak ranger, working out of the office in King Salmon. The concept of operations was that Marc, together with the Lake Camp ranger would conduct a series of three two-week patrols into the Aniakchak area to begin gathering data from an operational point of view. The logistics were terrible, weather worse, and it was all compounded by a complete lack of radio communication. Two patrols were successfully completed (without injuries or loss!) and the third was cancelled the day before departure due to a search and rescue incident developing at Brooks. [27]

Undeterred, Morris continued to push for a ranger presence. The recognition that a master plan was in the offing exacerbated the need to station a ranger at Aniakchak. For various reasons, therefore, George Stroud and Lynn Fuller, as noted above, stayed at the CRPA cabin for most of the summer of 1983. The following year, the pair returned. They lived there for less than three weeks and spent the remainder of the summer along the Katmai coastline. [28]

Seasonal NPS personnel did not return to Aniakchak for the next several years. In the meantime, however, the agency moved to establish a management presence. In November 1984, David Manski was hired as a resource management trainee. The terms of his contract called for him to serve a 22-month stint in the regional office, where he worked on problems common to many NPS units. Early in that training period, however, he learned that the focus of his work would be Aniakchak. [29] During that period, therefore, he spent some time working out of the King Salmon administrative office, working on both Katmai and Aniakchak issues. [30] In October 1986, Manski finally became the full-time, King Salmon-based Aniakchak resource management specialist. Inasmuch as he was the only staff person assigned to Aniakchak, he also worked on non-resource issues at the monument and preserve. [31]

The general management plan, which was approved in November 1986, called for Aniakchak to be staffed by two seasonal rangers as well as an RMS. As noted in the following section, Manski was successful in organizing various resource management activities at the unit. Rangers, however, have visited the unit only infrequently. In 1988, Frank and Penny Starr spent the summer at the CRPA cabin; they arrived on June 17 and remained until August 30. Manski left his position in September 1988 and the agency has not supported a full-time Aniakchak staff position since that time. It was not until 1991 that the next ranger stayed at the cabin. John Eppling and his wife Shakti, who served as a volunteer, were dropped off at the CRPA cabin on June 20 and stayed until September 12. Both the Starrs and the Epplings carried on the same general responsibilities that Stroud and Fuller had done beforehand; they established an agency presence, documented the area's natural and cultural resources, and apprised park management about human use levels. [32] Except for brief visits, rangers have not returned to Aniakchak since 1991.

Because the NPS has had such a transient presence in the area, personnel who worked there during the 1980s concentrated on informing park users of park regulations. No enforcement effort was in place. Many illegal activities may have taken place at Aniakchak during that period, but the agency had few ways of knowing of their existence. Agency staff knew that the creation of a resource protection program, when deemed necessary, would require a light aircraft and the budget necessary to support its use. [33] Those requirements were fulfilled in 1991 when the park filled a second pilot position. The following year the first arrest was made inside park boundaries; the citation was given to an individual who shot a caribou without a state hunting license. [34]

Resource Management Activities

Shortly after the passage of the Alaska Lands Act, park staff assembled the first Aniakchak Resource Management Plan. The plan, which was completed in April 1982, assessed the status of available scientific information and proposed a series of studies of park resources. It proposed five natural resource studies: 1) on the impact of sport hunting, 2) on the impact of subsistence use, 3) an evaluation of local weather conditions, 4) a basic inventory of vegetation and wildlife resources, and 5) a geological study of Aniakchak Caldera. It also proposed two cultural resource studies: 1) on the characteristics of subsistence use, and 2) a cultural resource baseline study. Of the seven studies, the highest priority was assigned to the cultural resource survey; second on the priority list was the geological study. [35]

As noted above, the NPS hired David Manski, the Aniakchak resource management specialist, in November 1984. Manski, however, was a trainee and was based in Anchorage until late 1986. Before his arrival in King Salmon, the agency's only resource management activities conducted since ANILCA had been Stroud and Fuller's observations during the 1983-84 seasons. Soon after Manski arrived, however, several studies were commenced which helped fulfill the needs listed in the 1982 RMP.

In 1987, a five-person interagency research team from the University of Alaska Fairbanks conducted two scientific studies inside Aniakchak Caldera. Koren Bosworth of the NPS worked on a vegetation inventory; during that time, 138 species of vascular plants and 130 bryophyte and lichen collections were obtained. That same summer, Gordon H. Jarrell of UAF conducted a small mammal study in the caldera. Barbara A. Mahoney and Gary M. Sonnevil, both from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, began a two-year fishery survey of Surprise Lake. And David Manski of the NPS coordinated the effort and conducted some biological sampling. The team operated from a base camp located at the west end of Surprise Lake. [36]

The following year, the NPS sponsored an updated, more detailed biological survey of the caldera. Mahoney and Sonnevil completed their fishery survey, and a research team headed by biologist Kristine Sowl inventoried the local birds, mammals, and vegetation. In addition, the team began a two-year limnology study of Surprise Lake. They collected physical, chemical, and biological information from the lake and from several tributary streams. In 1989, the second year of the limnology project, water samples were taken at two smaller caldera lakes and at four Katmai lakes, and the results were compared with those gathered the previous year. [37]

A limited amount of research during this period took place outside of the caldera. In 1987, as an adjunct to the caldera biological survey, Koren Bosworth, along with Mark Schroeder and Dave Manski, conducted a short-term botanical inventory along the coast. [38] In September 1988, a fisheries investigation was conducted along Albert Johnson Creek and the North Fork of the Aniakchak River as part of Mahoney and Sonnevil's caldera study. That same year, a survey of Aniakchak's coastal bird colonies was also carried out. That study was intended to duplicate a similar effort which the State had conducted ten years earlier. [39]

Biological research in the park was renewed in 1992. The agency sponsored a biological reconnaissance of the monument and preserve. Field camps, staffed with two NPS biotechnicians, were established inside the caldera and at the mouth of the Aniakchak River; in addition, a reconnaissance survey was made between Aniakchak Bay and Meshik Lake. Crew members collected both quantitative and qualitative data on the area's vascular plants, mammals, and birds. [40]

In order to gain information on the brown bear population in the area, the NPS funded and participated in an interagency study of bear migration. As noted in Chapter 14, the ADF&G had conducted a study of the Black Lake bear population in the early to mid-1970s. In 1988 the NPS, the ADF&G, and the F&WS joined forces in a follow-up to the earlier study. The study used the NPS's (and other agencies') staff but, like the earlier survey, it did not take place on NPS land. [41]

Although the NPS, in the 1982 Resource Management Plan, noted that a cultural resource survey was the number one project priority, such a study has not yet been attempted. Instead, bits and pieces of cultural resource information has been gathered, most of which has dealt with the historical site at the mouth of the Aniakchak River. Stroud and Fuller, during their visits in 1983 and 1984, gathered historical information on the old CRPA cabin; they also repaired it sufficiently to "make it habitable and reasonably bear proof." The GMP, which was completed in 1986, noted that "The existing public use cabin ... at the mouth of the Aniakchak River will continue to be maintained consistent with its historical design, and will be available to both public users and park staff." A short time later, David Manski updated the unit's RMP and specifically requested emergency funds for cabin stabilization. The request was approved, and the park requested the assistance of regional office staff in restoring the old bunkhouse. [42]

In June 1987, archeologist Roger Harritt, historian Sandra Faulkner, and historical architect David Snow visited the site. Harritt found several barabaras in the area and uncovered evidence that humans had been using the area up to 400 years ago, while Faulkner described the area within the historical context of Father Hubbard, the well-known lecturer and author that visited Aniakchak three times in the early 1930s. Snow investigated the building's structure and took photographs; based on that data, he prepared a set of elevation drawings. [43]

It was intended that the cultural resource team's efforts would result in a Historic Structure Assessment Report (an abbreviated form of historic structure report) for the bunkhouse. No HSAR, however, was ever prepared. The information collected in 1987 has since been augmented by information which was included in a National Register of Historic Places nomination form. Photographs and related information pertaining to the bunkhouse have been collected by other NPS cultural resources staff. [44] Park officials, in recent years, have shown a consistent interest in expending funds on restoring the cabin. That restoration, however, has not yet taken place.

The second highest research priority noted in the 1982 Resource Management Plan was for a geological study of the caldera. Since its publication, several caldera studies have been completed, some by the U.S. Geological Society and others by university personnel. Tom Miller and Robert Smith, the USGS geologists who had begun investigating the Aniakchak area in the mid-1970s, completed two studies on the calderas of the so-called Eastern Aleutian Arc, and a team of USGS investigators have discussed the caldera's tephra deposits. In addition, the region has attracted university geologists from as far away as Maine. [45]

No commercial mineral production has taken place in Aniakchak, and no oil and gas wells have been drilled in or near its boundaries. As previous chapters have illustrated, however, a small amount of interest has been shown in the copper porphyry deposits on Cape Kumlik, and intermittent interest in the area's oil and gas deposits has taken place ever since the 1920s. That interest, primarily in regards to oil and gas, has continued since the establishment of Aniakchak National Preserve in December 1980. (Hard rock mining and oil and gas drilling is prohibited in the monument.) Chevron U.S.A. and Arco Alaska obtained special use permits in 1982 and 1983, respectively, to visit the preserve and obtain geological samples. In 1984, five different oil companies showed an interest in the area's oil potential; the following year just one company, Shell Western, applied to visit the area. Interest in Aniakchak waned for the remainder of the decade. But in 1991, under Alaska Mineral Resource Assessment Program regulations, the Minerals Management Service obtained a permit for further exploration work; the agency's primary area of interest was "The Gates" area at the east end of Aniakchak Caldera. [46]

In 1993, the staff in King Salmon began to compile a new Resource Management Plan for the monument and preserve. The draft of the plan was completed in December of that year. The plan, however, has not yet been subject to public review.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap15.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2000