|

KATMAI / ANIAKCHAK

Isolated Paradise: An Administrative History of the Katmai and Aniakchak National Park Units |

|

| PART I: KATMAI NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE |

Chapter 2:

Creation of Katmai National Monument, 1912-1918

The Eruption of Mount Katmai

On June 6, 1912, one of the largest volcanic explosions ever recorded took place in the area surrounding Mount Katmai. The mountain was scarcely known to the outside world before that time, but the explosion was of such intensity that it thrust itself into prominence. An eruption of such a magnitude would have decimated entire populations had it occurred in a more populated area. [1] As it was, however, the area was so bereft of human activity that only one person, a tubercular, died from the effects of the eruption. [2]

Mount Katmai is one of a long string of volcanoes which comprise the Aleutian Range. The range is geologically quite active, even in comparison to other volcanic regions; that activity stems from the instability created at the intersection of the Pacific and North American plates. To give an idea of the Aleutians' activity level, 46 of the 79 known volcanoes in the Aleutians are known to have emitted ash, smoke, steam or lava at some time between 1741 and 1957. Of the historically active volcanoes, 26 have emitted ash, 25 smoke, 16 steam, and 13 lava. One has undergone a series of explosions. (Several peaks have emitted more than one type of material.) [3]

Therefore, those in the surrounding area found it of little consequence when the area north of Katmai Pass began to show signs of increased volcanic activity. Mount Katmai had never erupted during historic time, and there were no known Native legends which told of such an eruption. But Augustine Volcano, less than 100 miles to the northeast, had erupted at least twice during the previous century, and Mount Peulik, less than 70 miles in the opposite direction, had also erupted twice during the same period. As early as 1898, a passing observer had noticed that earthquakes and other evidences of volcanic action in the area surrounding Katmai Pass were "very frequent." Local Natives told him that one of the volcanoes near the pass--they did not say which one--emitted smoke occasionally. [4]

As noted in the previous chapter, economic conditions in 1912 were such that most of the residents of the Native communities within the present park were away for the summer. Many of the residents of Katmai, Douglas, and Kukak were working on Kodiak Island in conjunction with the canneries. On the Bristol Bay side of the Aleutians, at least some of the residents who normally lived in Savonoski, Brooks River and the other villages headed to the Naknek area for the summer. Although scattered residents remained at most of the Native villages, the only real center of activity in the area was the Kaflia Bay fishing station. Another fishing center was located at Puale Bay, 20 miles south of the present park boundaries. [5]

The first signs of an impending eruption were felt on June 1, perhaps a day or two earlier, when ominous trembles were felt. The quakes continued to gain in intensity during the next few days. By June 4 or June 5, the shocks were so severe that they were felt as far away as Kanatak, 65 miles to the southwest, and Nushagak, 130 miles to the northwest. The area around Mount Katmai probably emitted its first ejecta on the evening of June 5. [6]

Locals found the rumblings so ominous that they prepared to leave the area. Natives from Douglas to Katmai did not flee to Kodiak Island; instead, they congregated at the Kaflia Bay fishing station, evidently hoping to find a vessel that would afford safe passage out of the area. [7] Other Natives headed toward Puale Bay, but made it no farther than Cape Kubugakli when the eruption took place on June 6, and did not arrive at their destination until June 8. At Savonoski, "American Pete" reacted to the increased shaking by heading to the seasonal camp at Ukak to rescue some equipment. He witnessed the beginning of the June 6 eruption while there. Soon afterward, however, he retreated to Savonoski, gathered the remaining villagers and scurried across Naknek Lake. They covered the 60 miles to Naknek in a single day. According to Palakia Melgenak, there were also some people at a "fishing lodge" on Brooks Lake as late as June 6. Because the site was adjacent to the Iliuk Arm-Naknek Lake route traveled by the Savonoski residents, it is presumed that the fleeing villagers would have contacted their Brooks Lake compatriots if the latter had not already left on their own. [8]

The first big eruption took place at about 1 p.m. on June 6. Outbursts were almost continuous for the next two days; particularly heavy explosions were noted at 3 p.m. and 11 p.m. on June 6, and 10:40 p.m. on June 7. After June 8, strong eruptions continued for several weeks; after that point, activity was further reduced, although earthquakes and explosions were noted during the entire summer. [9]

Residents in many Alaska communities were well aware of the eruption. The first blast was so loud that it was heard in Fairbanks, 500 miles to the northeast, and it even carried as far as Juneau, 750 miles off to the east. Dawson City, in Yukon Territory, also heard the explosion. At Katalla, 410 miles east-northeast of the point of origin, residents reported that for three days the Katmai outbursts sounded "like blastings in quick succession." The earthquakes generated by the eruption were so strong that they were recorded in Washington, D.C. [10]

The ash, dust and grit spewed forth by the volcano spread far and wide. The ash was three to four feet deep at Katmai village, while at Kaflia Bay, the ash was piled three feet high. [11] The cataclysm dropped 6 to 12 inches of ash on Kodiak, and plunged the town into a gray gloom which lasted for most of the next 60 hours. [12] An estimated 3,000 square miles was covered by at least a foot of ash, and ten times that area was covered by an inch or more. "Appreciable" quantities of dust were recorded in Fairbanks, Juneau, and the Puget Sound cities.

To a lesser degree, the explosion's effects were felt even beyond Puget Sound. In Wisconsin and Virginia, the volcano was considered responsible for a "curious haze" noted in the days following the eruption. On a more general level, the dust veil produced a decrease in solar radiation, and for the last six months of 1912 mean temperatures were lowered throughout the northern hemisphere. [13]

Alaskans React to the Eruption

The press, both in Alaska and elsewhere, reacted immediately to the event. Within two days of the eruption, newspapers in San Francisco and New York were reporting on it. But few were certain as to the exact origin of the eruption. Reporters, at first, had no reliable information to use, and some speculated that Iliamna or Redoubt volcanoes had exploded. [14] But on June 8, C. B. McMullen, who was captain of the Dora, a supply ship to villages in the area, was able to get a wireless message out to Seward and other Alaskan cities. The Dora had been out in Shelikof Strait when the explosion occurred, just 55 miles east of it. He "pronounced" the smoke to have come from Katmai Volcano. Jack Lee, who was residing at Puale Bay, declared that "Katma Mountain" was the culprit, although he could not see the peak from where he lived. And "American Pete," who was probably closer to the explosion than anyone else, told cannery workers in Naknek that Katmai Volcano had been blown "sky high." [15] As a result, the press dutifully reported Mount Katmai as the site of the eruption. Scientists who investigated the area in the decade after the explosion corroborated the conclusions that these eyewitnesses had made. [16]

Not all, however, concluded that Mount Katmai was responsible for the eruption. Jack Lee, the Puale Bay resident who had opined in June that "Katma Mountain" had erupted, told the Seward Weekly Gateway on July 13 that he had just "visited Katmai in order to make a careful study of the cause and effect of the eruption." He returned convinced that the source of the eruption was "Mount Sevenosky." Notwithstanding the fact that "Mount Sevenosky" was not a known name at the time (and it has not been identified or located since), his story is also doubtful because volcanic activity was too intense at that time for anyone to have penetrated sufficiently close to be able to view the eruption site. His partner at Puale Bay, C. L. Boudry, was able to view the volcanic area from afar, and by July 21 he was quite aware of a "new crater" that had developed on Katmai Volcano. He did not publicize his newfound knowledge, however, and when he attempted to hike into the area, the smoke and acid forced him to turn back. And in 1913, Alaskans William A. Hesse and Mel A. Horner climbed partway up the slopes of Mount Katmai. Like Lee and Boudry, Hesse and Horner could see that some other peak was more active than Mount Katmai. The 1913 explorers, however, thought that the so-called "King of the Volcanoes" was an unnamed peak, southwest of Mount Mageik, which was later named Mount Martin for the 1912 explorer. [17] It was not until 1954 that a scientific team determined, based on the relative thickness of the ash layer and other factors, that the primary explosion site was Novarupta, a smaller mountain located seven miles west of Mount Katmai (see Chapter 12.) [18]

A key problem that had to be reckoned with was the welfare of the local residents. The U.S. Revenue Cutter Service ship Manning was in port at the time of the eruption, and its captain, Kirtland W. Perry, took personal responsibility for evacuating Kodiak residents to a safer locale. Five days later, Captain W. E. Reynolds, who was commander of the U.S. Revenue Cutter Service's Bering Sea Fleet (and Perry's supervisor), arrived in the Kodiak area from Unalaska and took command. [19] By June 19, he had visited the Afognak refugee camp, and after conferring with Perry and with various "leading men" of Kodiak, he decided to not reestablish the villages of the Katmai coast. Instead, he thought it better to centralize the former inhabitants at a new location. [20]

To implement his proposed strategy, Reynolds travelled to Seward, where he sent word of his plan to the Treasury Department in Washington, D.C. His suggestions were promptly approved, and on June 27 he headed south to implement them. By July 7, Reynolds was scouting a site on Ivanof Bay, 300 miles southwest of Kodiak, that had been recommended by an official at a nearby packing plant. [21] The Natives who accompanied Reynolds said that they were pleased with the site, which was to be called Perry in honor of the captain of the Manning, and by July 8, 78 former Katmai and Cape Douglas Natives had been brought to that spot. But by August 1, the new residents had grown weary of the new site, and they asked Captain Perry to be relocated. He obliged them by showing them a new coastal site 13 miles to the east, just north of Chiachi Island. By August 15, the Treasury Department had approved of the change in venue, and by August 25 the residents (which by now had grown to 92) had all been moved to the new site. They liked the site and decided to remain there, and it soon became known as Perryville. It is still a viable community; its 1990 population was 108. [22]

As noted above, some of the Natives who had formerly lived along the Katmai coastal villages fled to the Kaflia fishing station. Others headed south to Cape Kubugakli and Puale Bay. From there, they probably continued south to Perryville. [23] The Natives who had lived in (Old) Savonoski and the other communities in the upper Naknek drainage set up a village known as New Savonoski, which was on the south bank of the Naknek River five miles upriver from South Naknek. The village, now called Savonoski, remains an active community.

Some did not like the new environment, and tried to go back. Two families, in fact, moved from New Savonoski back to Old Savonoski and remained there for a year before the dust and heat drove them back to the new townsite. As "American Pete" noted in a 1918 interview, "Never can go back to Savonoski to libe [sic] again. Everything ash." [24] But if they could not live there again, they could use the area as a hunting ground. As later chapters note in greater detail, the vegetation and wildlife recovered rapidly in much of the region surrounding the east end of the Naknek Lake system, and as early as 1918 former residents of Old Savonoski were making annual bear hunts in the area surrounding the abandoned village. These hunts continued as late as 1939, and Brooks River persisted as a Native salmon harvesting area until the 1950s or 1960s. [25]

The National Geographic Society Shows an Interest

While the eruption depopulated a large area, and made it generally unattractive to those living in other areas of the Alaska Peninsula, it incited a great degree of curiosity and enthusiasm in the exploration and scientific communities. Within a fortnight of the initial eruption, the Research Committee of the National Geographic Society (NGS) had sprung into action. By providing him a research grant, the Society was able to persuade George C. Martin, a U.S. Geological Survey geologist, to travel to the area. His report was to be a first step in a systematic investigation of Alaskan volcanoes. He left Washington at once and arrived in Kodiak in early July. [26]

Martin was unsuccessful in his attempt to travel to the scene of the Katmai eruption. Instead, he spent a month on board the Manning, traveling on its various errands of mercy. His only visit to the Katmai coast during that period was a short visit to Douglas village. Later, aboard the Lina K., he visited Amalik Bay, and from there cruised down the coast to Takli Island, Katmai village, and on down to Puale Bay. Due to heavy cloud cover, he never even saw Katmai Volcano, and he did not venture inland from the coastal villages. [27]

After that trip, the National Geographic Society forgot about Katmai exploration for awhile. Other endeavors were assigned a higher priority. But Frederick Coville, a botanist who served on the NGS board of directors, refused to let the matter drop. Coville had undertaken previous research which had explored the biological potential of volcanic ash. He read an article by an old friend, Ohio State University botany professor Robert F. Griggs, which pertained to revegetation rates on Kodiak Island after the eruption. Coville, sensing an impending opportunity, wrote Griggs and asked if he would be interested in doing similar research in the area. [28]

Griggs accepted, and what ensued was the first of five Katmai expeditions, each of them sponsored by the National Geographic Society. In 1915, Griggs and two others spent from June through August in the Katmai country. His original focus was Kodiak Island, but as he noted, "I had come to study the revegetation, but I found my problem vanished in an accomplished fact." Therefore, he moved west to the more deeply buried country near the volcano. His party was dropped off at old Katmai village; from there, they wound up the Katmai River valley. The going was slow and treacherous, and they were unable to cross any of the major watercourses. They had to be content with a fine view of mounts Martin, Mageik, Trident, and Katmai. Even that degree of success was gained only after enduring weeks of low cloud cover. [29]

Griggs Discovers the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes

The 1915 expedition provided an enticing glimpse into the country to the west, and it convinced Griggs that a study of the eruption, including a "thorough exploration of the immediate environs of the volcano," was a valid subject for future research. Fortunately, the NGS agreed with Griggs's assertions, and the following spring sent him back to the area. Taking three other men with him, he returned to the mouth of Katmai River and headed up the valley with the intention of climbing Mount Katmai. They reached the summit on the afternoon of July 19, 1916. After an 11-day spell of bad weather, the party climbed the mountain a second time. Having observed steam clouds on the west side of Katmai Pass, they spent the following day climbing Mageik Creek to get a closer look. They got almost up to the pass, and saw little out of the ordinary. Griggs and Lucius G. Folsom, his hiking companion, were getting ready to turn back when he "caught sight of a tiny puff of vapor in the floor of the pass." [30] The fumarole intrigued them, and by the time they reached the pass they found hundreds of steam jets scattered through the area. A large puff of steam off to the west encouraged him to climb a nearby hillock for a better look, and

there, stretching as far as the eye could reach, till the valley turned behind a blue mountain in the distance, were hundreds--no, thousands--of little volcanoes like those we had just examined. They were not so little, either. ... Many of them were sending up columns of steam which rose a thousand feet before dissolving. After a careful estimate, we judged there must be a thousand whose columns would exceed 500 feet. [31]

Griggs and Folsom, enraptured by what lay before them, wandered down the valley for several miles. Griggs got as far as a view of Novarupta, and described it as "a plug of lava ... which was formerly rather violently explosive," before the party had to return to its camp on the coastal side of Katmai Pass. Griggs hardly slept that night, and was readying a return visit the next day when the weather abruptly changed. Rising water in Katmai River caused him to be cautious; reluctantly, he ordered the party to retreat to Katmai Bay. Ten days later they left the area. [32]

The National Geographic Society was enthusiastic about the new discoveries, and "in view of the extraordinary conditions of the Katmai region, unparalleled anywhere in the world," granted Griggs an additional $12,000 to make an extended examination of the so-called "Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes." [33] Griggs headed a party of ten men which returned to the area the following year; they included a topographer, a zoologist, a chemist, and two botanist, but curiously enough no geologist. The party arrived in late June, and began its investigations at a point several miles south of Katmai Bay; from there it followed the west bank of Katmai River and ascended Martin Creek. On July 4, Griggs and Walter Metrokin, a "famous one-handed bear hunter" who had also accompanied him the previous year, trekked up to the pass together. Four days later, most of the rest of the party did the same, and established a camp near the saddle. All were initially agog at what they saw. They eventually split up into work details. They spent about a month on the west side of Katmai Pass; during that time, the party descended the Ukak River valley at least as far as the end of the ash flow, and beyond it almost to Old Savonoski. Members also climbed Mount Katmai (some for the second time) and explored the upper Katmai Canyon as far as the so-called Katmai Lakes. After some additional exploration, the party headed back down to the coast and left the area. [34]

Toward the Protection of the Volcanic Area

By the time the 1917 expedition had been completed and the result of its investigation published, the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes had become well-known to many members of the scientific community. But because the National Geographic Magazine was such a popular publication--the Society had some 650,000 members at the time--the area had also become familiar to a broad sector of the general public as a natural wonder and a scenic masterpiece. [35] Those who directed the Society were convinced that the area should be set aside as park land in order to preserve the unique qualities which had so recently been investigated.

The National Geographic Society was not the first organization which recognized Katmai's park potential. The beauty of the country, in fact, had been admired even before the cataclysm which tore it asunder. In 1880 Ivan Petroff, the first Alaska census taker, had led a party from Savonoski to Katmai Bay via Katmai Pass. Speaking about his trip in an 1881 article, he prophetically noted that

When we made this portage last October, we were struck by the fact that the tourist might land at Katmai, and in one day's foot travel stand with us at the summit of a mountain pass, the divide proper of the peninsula, where he would be compassed on every hand by the grandest visions of Alpine scenery, snows, and glaciers. [36]

Others praised the qualities of the Shelikof Strait coastline. An English adventurer, H. W. Seton-Karr, noted after an 1886 visit that a cruise in a bidarka from Katmai south to Unga would be unequalled, both for scenery and sport hunting. Thirteen years later, several members of the Harriman Alaska Expedition spent a few days camped on Kukak Bay. While there, they walked up the slope behind their camp and found themselves suddenly at the edge of a 2,000-foot precipice, across from which was a glacier that "fairly took their breaths away." The visitors to Kukak Bay told the remaining expedition members that they were "well pleased with their expedition," and were henceforth boosters of the Katmai country. [37]

With the 1912 eruption, much of the topography which had been admired in earlier years was irreparably altered, and for the next two or three years the countryside surrounding Mount Katmai lay inaccessible to the outside world. Neither Martin in 1912 nor Griggs in 1915 spoke in very endearing tones about the beauty of the region, primarily because neither party was able to penetrate beyond the coastal valleys and canyons. When Hesse and Horner made a reconnaissance of the area in 1913, they saw enough of the area to report dramatically of "thousands of small fumaroles issuing columns of steam and smoke, and the ground was a maze of wide jagged cracks like paths of lightning." [38] But they did not make their observations known until after Griggs asked Horner about them.

The movement to create Katmai National Monument began on July 31, 1916, when Robert F. Griggs and Lucius G. Folsom encountered the thousands of fumaroles beyond Katmai Pass. As soon as they viewed them, they were certain that they had discovered one of the great wonders of the world. As Griggs later put it,

The sight that flashed into view as we surmounted the hillock was one of the most amazing visions ever beheld by mortal eye.... The first glance was enough to demonstrate that we had found a miracle of nature which, when known, would be ranked with the Yellowstone, the Grand Canyon, and other marvels, each standing without rival in its own class. [39]

By the time he had returned to camp that night, the elated Griggs was already taking his thoughts of the scenery beyond admiration. Perhaps with the convenience of hindsight, his memories that night were as follows:

I recognized at once that the Katmai district must be made a great national park accessible to all the people, like the Yellowstone. To make it known, to have it set aside as a National Park, and to secure the means necessary for its development would, I foresaw, require a tremendous amount of effort. [40]

His thoughts the next morning were every bit as occupied as those of the night before. How, he wondered, was the public going to get to this remote region? He had practically proven, after several attempts, that large numbers of people could not be landed through the surf at Katmai Bay. Was a suitable harbor available nearby? From what he knew at the time, the possibilities were not too encouraging. [41]

Griggs' observations on his 1917 trip were colored by the potential value that Katmai might have as a tourist destination. For instance, when he and Walter Metrokin climbed up to Katmai Pass on July 4, he was relieved to find that the fumarole activity was just as active as it had been the previous year. From that, he concluded (incorrectly, as it turned out) that geologic activity in the valley had reached a stable plateau and would continue without much change for years into the future. Generations of tourists, therefore, would be able to enjoy the wondrous display. The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, he opined, was "one of the greatest wonders of the world, if not indeed the very greatest of all the wonders on the face of the earth." [42]

Griggs made further remarks which appear, in retrospect, to have stressed the area's eligibility as a candidate for a national park unit, a tourist area, or both. His 1917 ascent of Mount Katmai, for example, was his third, but he chose to be more hyperbolic in his writeup of this climb than of his previous two trips. He judged Katmai to be "the greatest active crater in the world; furthermore, he called it "a far grander spectacle to look upon" than the inactive and larger craters of Haleakala and Crater Lake, both of which were already within national parks. He noted that Katmai Canyon was "almost as deep as the Grand Canyon;" on a more general level, he felt that the canyon's colored rock walls, the waterfalls, and distant lakes reminded him of the Grand Canyon and the Canadian Rockies "all put together." In describing all he had seen, he declared that "for sublimity of scenery this place has no equal in the whole world." [43]

From the time of his trip until Katmai National Monument became a reality two years later, Griggs became a leading publicist and lobbyist for Katmai; he also became the area's pre-eminent geological authority, even though his training was in biology. When he returned to Washington, for example, he was relieved to find that the National Geographic Society's officers were as interested in publicizing the area as he. Griggs entitled the article on his trip "The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes" even though he included only two photographs and five pages of text on the area beyond Katmai Pass. The Society's directors were old hands in the cause of national park promotion, and when the article was published in the January 1917 National Geographic Magazine, it signaled the opening volley in the Society's crusade to establish a new park area. [44]

The National Park Service Gets Involved

During the same period, the Society made an initial foray into the legislative arena. As Horace Albright noted in an interview more than half a century later, the idea of a government reservation in the Katmai district was first broached in the midst of the negotiations which led to the declaration of Mount McKinley National Park. The McKinley bill passed Congress on February 19, 1917, and was signed by President Woodrow Wilson a week later. But no more governmental action for a park at Katmai took place for another year. [45]

By the time the NGS directorate received the data from the 1917 expedition, the Society was confident that it had gathered enough data to support its claims that the region constituted one of the greatest scientific and scenic wonders of the earth.

The following February the Society laid out its case to the public. It published the results of its 1917 work in an article whose title, "The Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes: An Account of the Discovery and Exploration of the Most Wonderful Volcanic Region in the World," announced that the Society had more than just a scientific interest in the area. Neither this article nor that from the previous year specifically mentioned that the volcanic district should be preserved in a national park. But the idea was nevertheless implicit. As Griggs himself later noted, "As a result of this report, the Katmai National Monument ... was created." [46]

As the following paragraphs suggest, Griggs's quote probably overstates the report's role in the creation of the monument; in addition, the statement is an oversimplification because it suggests that little effort was required and no opposition existed to the proposed land reservation. In fact, both local interests and Interior Department officials questioned the necessity for withdrawing such a large, unknown tract. Beyond that, the backers of a monument had to convince many whose priorities lay elsewhere. The United States, at the time, was in the midst of World War I in 1918; matters pertaining to the national parks, as a consequence, were of secondary importance. To most Americans, moreover, the creation of a park in a remote section of Alaska Territory was an issue of little or no concern.

Most of the efforts that led to Katmai's establishment, therefore, were low-key actions partaken far from the legislative arena. The campaign was organized and conducted by several officers from the National Geographic Society, along with Dr. Griggs. Together, they mentioned the idea to various Department of the Interior officials, then to other governmental representatives.

Little documentation exists regarding the methods that were used to obtain Interior Department approval, but evidently little trouble was encountered in obtaining it. An important part of the approval process may have been the fact that Franklin K. Lane, who had been Woodrow Wilson's Secretary of the Interior since 1913, was also on the Society's Board of Managers. Lane, therefore, was doubtless aware of, and probably interested in, the Society's Katmai expeditions. Another point in the monument's favor was a worry, among some geologists, that Yellowstone's geysers were declining; Katmai, therefore, was suggested as a possible replacement. [47]

Soon after the publication of Griggs's article in the February 1918 National Geographic Magazine, its editor, Dr. Gilbert H. Grosvenor, brought up the idea of a park to Secretary Lane. He, in turn, suggested that he mention the idea to the officials at the newly-created National Park Service. Grosvenor therefore requested a meeting with Stephen Mather, NPS director and Horace Albright, the agency's assistant director, in Washington's Cosmos Club. Professor Griggs also attended. The meeting was quite informal; Mather, Albright and Grosvenor were old friends and leaders in the conservation movement. Albright, at the time, was the agency's acting director; Mather had suffered a nervous collapse in the fall of 1916, and was still recovering. [48]

The real work of shaping the idea of a park from an idea into a legislative package took place during the spring of 1918 during a series of discussions at the Cosmos Club which were largely conducted by Grosvenor and Albright. Secretary Lane was kept informed of all developments. [49]

The National Geographic Society, based on Griggs' original suggestions, hoped that the Katmai district would become a national park. Charles Sulzer, Alaska's delegate to Congress at the time, was in enthusiastic agreement on the subject, noting that "we could gain some useful publicity to this great natural phenomenon of the North by creating a national park there." [50] But the National Park Service had just weathered a strong wall of opposition in the struggle to create Mount McKinley National Park. The Service recognized that trying to press for another Alaska national park would sap whatever good will the agency had established with Congress; besides, other areas were of more interest than Katmai as potential national parks. As Albright recalls it, "I simply had to tell the National Geographic people--Dr. Grosvenor, Associate Editor and Vice President John Oliver LaGorce, and Dr. Griggs--that a national park was out of question, and that a national monument was the only kind of reservation that would make possible the protection of Katmai." [51]

The Society weighed the pros and cons of national monument status for the Katmai district. A national monument, in theory at least, conferred just as much protection as a national park. It could be accomplished via a proclamation under the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906, which permitted the president to create national monuments in order to protect "objects of historic or scientific interest" on public lands. [52] By issuing a presidential proclamation, the agency could avoid a bruising legislative battle like that which had been waged over Mount McKinley.

Grosvenor and his fellow officers initially objected to the idea because they did not feel that the Antiquities Act could be used to reserve large-scale land areas. Albright, however, noted that both Grand Canyon and Mount Olympus national monuments had been established under the act's provisions. Eventually, the Society agreed to push for a monument. [53]

Albright himself began the next step, the preparation of a presidential proclamation. It was a team effort. The text appears to have been influenced by Dr. Grosvenor and Dr. Griggs. George C. Schweckert, the NPS attorney, "probably" prepared the first draft. [54]

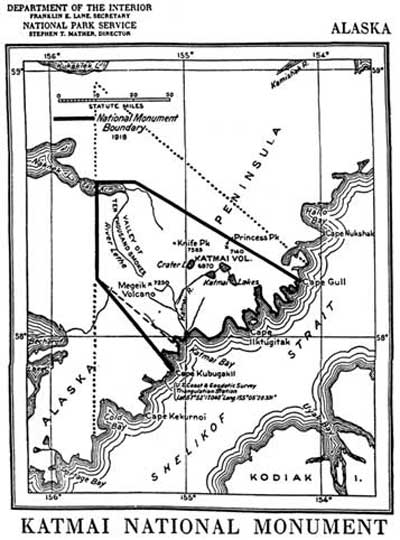

Griggs, who had the field experience, proposed the boundary lines (see Map 3). His original boundary proposal called for a large triangular area which began just west of Puale (Cold) Bay. From there the boundary line went due north to a point along American Creek midway between the western end of Lake Coville and Nonvianuk Lake. The boundary then went east-southeast until it reached Shelikof Strait just north of Kaflia Bay. [55]

The proposed proclamation was then given to the General Land Office (GLO) and the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) so that the proposed boundaries might be checked. [56] These agencies were given the responsibility of providing data on land ownership or mining activities within the proposed reservation. General Land Office personnel found little of interest. [57] The National Geographic Society, in its role as advocate, also hoped that Geological Society investigators would likewise find little of interest. Explorers who had passed through the area before the eruption, after all, had found few areas of interest, and descriptions of the post-eruption landscape clearly indicated that most of the previous resources in the volcanic area had been buried by lava and ash.

But USGS surveys had pointed out several promising mineral discoveries. Puale Bay, for instance, had been the scene of an oil boom from 1902 to 1905, and operations had been intermittently active since that time. [58] In 1912, George Martin had seen commercial possibilities for the ash deposits he had seen along the coast. At about the same time, Charlie McNeil and Norman B. Cook found copper-bearing veins about 17 miles inland on a stream running into a "southwest bight" of Kamishak Bay. (The stream was probably McNeil River.) In 1915, Fred and Jack Mason discovered placer gold along a small stream just south of Cape Kubugakli. Two years later, Robert Griggs discovered that "There are some places where one can gather crystals of sulphur, almost free from impurities, by the bushel." In 1918, Alex Grant found placer gold on American Creek; the same year, the Geological Survey reported that work was continuing at the Shelikof Mining Company's prospect near Kukak Bay.

Many of these discoveries, to be sure, were outside of the boundaries of the proposed monument, and most turned out to be of short-term duration and were economically insignificant. [59] But enough was known about the mining activities surrounding Puale Bay and Cape Kubugakli, both of which were within the proposed monument boundaries, that they were brought to the attention of Secretary Lane. [60]

In order to clarify their position on the matter, Albright talked to some of the geologists who had been asked to review the proposal. Some were opposed to the withdrawal, primarily because "regardless of whether or not the Katmai country was valuable commercially, it was so devastated and uninviting that it was absolutely safe in its existing state and there was absolutely no necessity for giving it any governmental protection." [61]

While the monument proposal was being investigated by the GLO and the USGS, an Interior Department official sent the details of the plan to Charles Sheldon, a longtime member of the Boone and Crockett Club. The Club, a prestigious organization of sportsmen and conservationists, had recently played an integral role in the setting aside of Mount McKinley National Park as a game refuge, and Sheldon hoped that the Katmai proposal would also include a large area of high quality wildlife habitat. Sheldon, therefore, "suggested that the limits of the area occupied this national monument should be so drawn as to create a refuge for bears." But Sheldon, who had lived in Alaska for several years, knew that the monument's wildlife resources had to be downplayed. In 1918, a wartime scarcity of beef was causing many Alaskans to lobby territorial officials for a repeal of all legal protection for bears. Boone and Crockett members, therefore, responded by quietly pushing for a proclamation, all the while cautioning that "the word bear should never be mentioned in connection with the establishing of this monument." The Club's president, George Bird Grinnell, told Club members that "The boundaries of this monument recommended by [Sheldon] ... are so drawn as to create a refuge for bears." But neither NPS nor NGS documents reveal that the Boone and Crockett Club had much influence in the matter. [62]

President Wilson Proclaims Katmai National Monument

After the GLO and the USGS had completed their investigation, NPS Director Mather (who by now had actively assumed his post) was ready to present the proclamation to Interior Secretary Lane. Griggs, who had been asked to consider two smaller monument areas, vigorously defended his original boundaries, going so far as to invoke the vision of Jefferson and Seward in their respective quests for the Louisiana Purchase and Alaska. He argued, in particular, for the inclusion of the Puale Bay area because he felt it might be devastated by some future eruption. But Secretary Lane, perhaps on advice provided by the Geological Survey, insisted that Griggs' proposed boundaries be reduced to "exclude all lands except those devastated by the great eruption." Lane thus chose the larger of the two alternative proposals which Griggs had crafted. Excised areas included the large triangle of land surrounding Puale Bay, and a long, narrow band located just north and northeast of the original monument boundaries. [63]

The language of the final proclamation, which Mather and Lane then passed on to President Wilson, warned "all unauthorized persons not to appropriate or injure any natural feature of this monument or to occupy, exploit, settle, or locate upon any of the lands reserved by this proclamation." The implicit prohibition against mining in the Katmai proclamation was thus distinctly different from language contained in the recently-passed Mount McKinley park bill. (In 1925, Glacier Bay National Monument was created by presidential proclamation, and in 1936 Congress passed a bill allowing mining activities at Glacier Bay; for more than 50 years, therefore, Katmai was the only large Alaskan NPS unit that prohibited such an activity.) [64]

The Society was convinced that the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and the related volcanic features did indeed "stand preeminent among the wonders of the world," and that nowhere else on earth was there "anything at all similar to this supreme wonder." But one nagging question which had come up during the deliberations concerned the permanency of the volcanic wonders. Were the steaming vents really evidence of a vast underlying body of molten magma, or did they only indicate the vaporization of surface water as gradually cooling products of the eruption? In other words, were the cauldrons and "smokes" long lasting phenomena, or would they fade away in just a few years? Griggs, who had seen the valley in both 1916 and 1917, was convinced on his second trip that "everything was just as it had been the previous year." [65] But others, both in the Society and the NPS, wanted more evidence.

To answer their concerns, the Society organized another expedition to the Katmai district in the summer of 1918, even though a larger expedition had been deferred because of the war. Only two botanists, Jasper Sayre and Paul Hagelbarger, made the trip; both had also participated in the 1917 expedition. Unlike previous adventurers, the two botanists arrived by way of the Naknek River, then crossed Naknek Lake to the lower end of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. During their excursion, the two men also encountered "three good-sized lakes not shown on any map," now known as lakes Brooks, Coville and Grosvenor. [66]

Regarding the primary purpose of their trip, the photographs they took and the temperatures they recorded caused them to conclude that the condition of the fumaroles was "exactly the same" as in 1917. Writing in a National Geographic Magazine article which appeared in the spring of 1919, its editors stated that

It is clear that the studies made thus far give no indication of any diminution in the Smokes, much less do they suggest a probable date for their extinction. It may be considered established, therefore, that the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes is a relatively permanent phenomenon. [67]

With all parties satisfied that the monument was both worthwhile and of lasting value, Secretary Lane took the completed proclamation over to the White House. There, on September 24, 1918, President Wilson issued Proclamation No. 1487, which reserved "approximately 1700 square miles" to create Katmai National Monument. The signing was witnessed by Secretary of State Robert Lansing. [68]

The new monument was at last a reality. The area included within its boundaries was relatively modest by today's standards; it included less than 30 percent of the present park and preserve. A "modest reservation" of approximately 1,088,000 acres, it embraced little more than the area of active volcanic peaks surrounding Mount Katmai, along with the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and most of Iliuk Arm. That area, small as it was by Alaska standards, was still half the size of Yellowstone National Park and 50 percent larger than the state of Rhode Island. [69]

The purposes of the new monument were consistent with the amount of land reserved. Four reasons were given in the proclamation: 1) the recognition of the importance of Mount Katmai and the eruption which issued forth from there, 2) the opportunity to learn and appreciate the field of volcanism because the eruption had taken place so recently, 3) because it provided the opportunity to protect an active volcanic belt (as opposed to the "present dying geyser field of the Yellowstone"), and 4) because the "great magnitude" and "inspiring spectacles" contained within ensured "popular scenic, as well as scientific, interest for generations to come." In a phrase reflective of that wartime period, the proclamation even went so far as to imply that creation of the monument would be an "inspiration to patriotism." [70]

When compared with the political process required to create today's NPS units, it seems remarkable that a monument such as Katmai could have been created so simply. It also seems remarkable that a single organization--in this case the National Geographic Society--was able to play such a dominant role. There appears to have been an element of collusion involved in the monument creation process because of the social relationships shared by the Secretary of the Interior, the NPS hierarchy, and the National Geographic Society leadership. The easy sociability of those men doubtless made monument designation an easier process than it otherwise might have been.

It seems patriarchal to conclude that the National Geographic Society, so quickly and without fanfare, was able to convince Interior Department officials and the President to reserve such a large land mass. But that is precisely what took place. No other groups outside of government appear to have known that such a monument was being proposed. Among Alaskans, Governor Thomas Riggs (who had been working in the territory for years and had been appointed to his position just a few months earlier) may have been the only one who was even aware of the proposal, and he was given only an general outline of the proposed action. (Riggs protested the monument idea; he also requested that a geologist survey the area before designation took place. His pleas fell on deaf ears.) [71] During the early years of the NPS, the only standard process--in Alaska or elsewhere--by which proposed park areas were checked for their resource values were the GLO and USGS investigations. Outside groups, local residents, and other interested individuals were typically given no opportunities to either support or protest proposed parks. In the case of Katmai, the NGS does not appear to have covered up information which may have diminished park values, but their position as advocate made it difficult for them to objectively assess the monument's resources. [72]

As time would prove, a major resource value on which the monument idea had been based--the fumaroles--would decrease in importance. Other aspects of the geologic landscape, however, would continue to remain much as they had been for decades to come. Other priorities, moreover, would eventually shoulder their way to the forefront, and as a result, the public's perceptions of the monument would change. The establishment of Katmai as a national monument, in September of 1918, was the beginning of National Park Service management of the area. The agency still manages the district, but the actions it has taken to effect that management have reflected a continuing evolution in public attitudes toward park resources. That evolution is still in process today.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 24-Sep-2000