|

KATMAI / ANIAKCHAK

Isolated Paradise: An Administrative History of the Katmai and Aniakchak National Park Units |

|

| PART I: KATMAI NATIONAL PARK AND PRESERVE |

Chapter 3:

An Era of Neglect: Monument Administration Before 1950

As noted in Chapter 2, the only parties responsible for the impending creation of Katmai National Monument were the National Geographic Society and various agencies within the Department of the Interior. Few others were even aware that the idea was being considered. It was only after President Wilson signed Proclamation No. 1487, in September 1918, that outsiders learned that the area had been protected.

Reactions to the New National Monument

Thanks to the publicity generated by annual articles in National Geographic Magazine, many Americans were aware of the Katmai country at the time of its designation as a monument. Most, however, knew little more than they had read in the Society's articles. National Geographic subscribers probably approved of the proclamation, but the vast majority of citizens cared little if at all about the fate of such a remote, unpopulated area. Surprisingly, the creation of the million-acre reservation elicited few if any news reports or commentary, either in Alaska or the United States. With the World War in its waning stages, the glut of overseas war bulletins was far more important to the average reader than a national monument in a far-off corner of Alaska. [1]

The National Park Service, not surprisingly, was a strong supporter of the new monument. Its 1918 annual report stated that "The American public owes deep gratitude to the National Geographic Society for the discovery and exploration of this unique exhibit." Horace Albright, its acting director, spoke with candor when he told the Alaska governor that

We feel that the establishment of the Katmai National Monument cannot possibly be anything but a benefit to the people of Alaska. We are in the tourist business and are engaged in attracting the attention of the people of America to its scenic resources. Whether people visit the Katmai region or not, we want them to know that some day it will be an interesting place to go, and besides it gives us an opportunity to promote Alaska as a touring ground. [2]

Most Alaskans, however, did not approve of the new monument. Few, to be sure, knew what lands were contained within the reservation. Instead, they were opposed the idea of government reservations in general because they regarded withdrawals as a "locking up" of resources which should have been available for local residents. Territorial citizens were still seething over the closure of Alaska's coal and oil lands which had been imposed on Alaskans in 1906 and 1910, respectively. The new reservation merely reopened earlier wounds and stirred a new wave of anger and resentment. [3]

Thomas Riggs, who governed the territory from 1918 to 1921 and a longtime Alaskan, typified local attitudes when he said that "practically all of the reservations should be eliminated and the laws of the United States made to apply." He further noted that "Katmai National Monument serves no purpose and should be abolished." He chided Acting Director Albright for allowing its creation; he noted that volcanic ash made the soil "peculiarly fertile," stated that the monument contained oil, and decried that "there is no possibility of the Katmai National Monument ever becoming a favorite place for tourist travel." Riggs was fed up with a system in which "the Territory has been at the mercy of any faddist who could go to Washington and get the proper endorsements." [4] The governor, obviously frustrated at the tactics of outside conservationists, stated that

For the sake of the future of Alaska, let there at least be no more reservations without a thorough investigation on the ground by practical men and not simply on the recommendation of men whose interest in the Territory is merely academic or sentimental. [5]

Despite the broad denunciations of the action taken within the territory, the objections were primarily philosophical. No one knew of instances in which individuals were deprived of a living because of the proclamation. The land had no agricultural value, it contained less than ten acres of private (Russian Orthodox Church) land, it was well away from established transportation routes, and access to the monument's main features was almost prohibitively difficult. Instead--and the criticism is valid considering the existing state of regional development--many criticized the action because the creation of the reservation would prevent development interests from ever knowing what resources were contained within.

As noted in the previous chapter, the Katmai area was the scene of scattered mining activity at the time the monument was created. Those who were out prospecting, of course, had no idea that a monument was being contemplated. And as it turned out, their activities caused no friction with governmental authorities. In large part due to the elimination of potential parkland around Puale Bay, no active mining areas were placed within the boundaries of 1918 monument. George Martin had noted the commercial importance of ash deposits and Robert Griggs had mentioned the preponderance of sulphur crystals, but there is no indication that entrepreneurs during this period had ever attempted to extract these materials for commercial gain.

Early Monument Visitors

During the half decade after the creation of the monument, the monument continued to be publicized, though to a lesser extent than it had been during the 1912-1918 period. The most conspicuous group of visitors came from the National Geographic Society. In 1919, Robert Griggs led his fourth Katmai expedition. Griggs and the main party entered the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes by way of Katmai Pass, but four members brought the main supplies into the area by way of Naknek, Naknek River, and Naknek Lake (as the two-man 1918 expedition had done). A tent base camp was established at the east end of Iliuk Arm. The party of nineteen, which included five scientists, two topographers, two photographers, and ten assistants, undertook a diversity of tasks which led them to Brooks Lake, Lake Coville and Lake Grosvenor as well as the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Perhaps because he had already given a thorough description of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes in previous articles, Griggs's writeup of the 1919 trip concentrated on the countryside adjoining the monument. Griggs spared few adjectives in lauding the Naknek River system's salmon runs--in particular the Brooks River run--and in describing Katmai's value as a bear, moose and waterfowl refuge. [6]

In 1923, Walter R. Smith and R. K. Lynt led a U.S. Geological Survey expedition which included most of the area within the existing monument; the report also described the area as far west as Brooks Lake and southwest to Becharof Lake. That same summer, Kirtley F. Mather and R. H. Sargent led another USGS expedition which investigated the coastal valleys from Cape Douglas north to Paint River, and also covered Battle Lake and the Savonoski River, Moraine Creek and Funnel Creek drainages. The reports which followed those explorations indicated that few if any rich areas of mineralization were likely to be found in either the monument or the immediate vicinity. Before the reports were published, as noted above, Alaskan interests had been angry at the creation of the monument, in part because of the perception that valuable minerals would be made inaccessible. The reports, therefore, helped create a somewhat friendlier public attitude toward the monument. [7]

Local interests were also mollified when attempts were made to develop the area's tourist potential. During his 1919 expedition, Robert F. Griggs discovered an excellent harbor at the head of Amalik Bay, which he called Geographic Harbor in honor of his longtime sponsor. He noted that it would be easy to bring tourists there, and added that

Only 50 or 60 miles of automobile road is needed to open up all the wonders of the area to the public. When that is constructed, the traveler may tour the Katmai National Monument as easily as he now visits the Yellowstone. [8]

The Alaska Road Commission (ARC) responded to Griggs's suggestions in 1921 by visiting the area and making an informal survey for a thirty-mile road. The ARC's report that year gave development backers scant hope that a road into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes would ever be built. The reconnaissance report noted that

It appears that a road from any Pacific entrance would be prohibitive in cost, if not impossible. The deep ashes mentioned drift around like snow with every wind. It lies on the steep slopes like so much ground coffee and is always ready to slide when disturbed. Until vegetation has again penetrated it, and formed a sod or soil as a binding, it will not pack and can not be held in place. [9]

The glum report, however, did not dissuade those who hoped to open up Katmai to tourism. Governor Scott Bone, for one, recommended road construction in his annual reports for 1922 and 1923. [10] The governor's reports for 1924 through 1931 noted that "When [Geographic Harbor] can be developed and an auto road approximately 30 miles in length constructed into the area, it will be readily accessible and draw many visitors." The NPS, which also hoped that the area might be developed, was optimistic enough to declare in 1926 that such a road "may in the future afford a fine entrance to the region." No government agency, however, seriously considered constructing such a road, and no organizations outside of government advocated road construction either. The National Geographic Society, having won monument status for the volcanic area, made no efforts to develop the recently protected area. Alaska's governors were doubtless aware that the construction of such a road would require superhuman skill, result in high maintenance costs, and would, under the best of circumstances, attract few visitors. But that did not stop them from pushing for highway construction. [11]

The 1920s brought large numbers of tourists "to the westward" (as southcentral Alaska was described at that time) for the first time. Before World War I, few tourists who traveled up the Inside Passage ventured far from the various of southeastern Alaska ports. But with the construction of the government-sponsored Alaska Railroad from 1915 through 1922, destinations such as Seward, Anchorage, Mount McKinley National Park and Fairbanks became newly accessible. Katmai, as a result, was located much closer to the regular tourist routes than it had been previously. Unfortunately, however, Katmai was still over 200 miles from the nearest port commonly used by tourists. Besides, it had no transportation infrastructure. Tourists, therefore, had to make a considerable effort to see the newly created volcanic landscape. Few were willing to be so adventurous. [12]

Despite the difficulties in reaching the monument, a few tourists dribbled in during the 1920s. In 1923, a party of forty spent two weeks exploring the area. As part of their trip, they hiked Mount Katmai. Fifteen others also visited that year, and another seventeen in 1924. A four-person party headed by D. W. Handy of Vermont visited in 1925. [13] Perhaps the best known tourists were Captain Jack Robertson and Arthur Young, a pair of adventurous filmmakers who travelled throughout the territory in search of footage. In 1925 the two produced, directed, and starred in The True North, a seven reel travelogue of their trip to Siberia. Robertson and Young took an indirect route; going by way of Fairbanks, they shot rapids along the Yukon River, watched a spring break-up, and made a canoe from a moose hide. They also visited the Katmai country, and observed Mount Katmai, the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, and spawning salmon. Using much of the same footage, the pair released Alaskan Adventures in 1926. Four years later, Robertson included Katmai scenes along with those from other Alaskan venues to produce a five-reeler called The Break Up. [14]

Although the monument attracted few sightseers, the potential for visitation to the newly-created volcanic wonderland encouraged several to promote the area. Throughout the 1920s, Kodiak advertised itself as the outfitting headquarters for trips to the monument, perhaps because it had been the jumping-off point for some of the National Geographic Society trips to the Valley of the Ten Thousand Smokes. The Alaska Railroad offered to arrange trips to the monument. In the early 1930s a ship captain from Kanatak, Bob Hall, offered to take tourists into the Valley. He had already visited the valley with a pack horse team, and felt that pack horses taken in from Katmai Bay were the best way to access the heart of the monument. And in 1931 an Alaska resident told Horace Albright, the NPS director, that the monument would soon become "a regular port of call for the Alaskan steamers." No one, however, was willing to make a substantial investment in Katmai tourism development. [15]

Initial National Park Service Management

Although both scientists and tourist entrepreneurs expressed an early interest in the area, the National Park Service largely forgot about Katmai for the first twenty years after its establishment. The analogy which Ernest Gruening used to describe Alaska is relevant here; this period comprised Gruening's "era of total neglect." [316] The unit was ostensibly managed as an adjunct to Mount McKinley National Park. (Glacier Bay, which was established in 1925, was managed in a similar fashion.) But the National Park Service was unable to provide the wherewithal to actively manage either unit, and there is no evidence that Harry Karstens, the first superintendent for Mount McKinley, exerted any effort in managing either Katmai or Glacier Bay during his seven-year tenure (1921-1928). Given the meager resources available, Mount McKinley was hard enough to manage itself. Both Karstens and his successor, Harry Liek, were stretched to the limit trying to maintain a minimal presence over the countryside surrounding North America's highest peak. At no time during the 1920s and 1930s were there more than six employees, permanent or seasonal, on the Mount McKinley park staff. [17]

Compounding the lack of staff was a lack of money. Prior to the coming of the New Deal programs of the 1930s, national monuments were perceived to be areas designed to be protected from encroachment, whereas national parks were intended to be "resort[s] for the people to enjoy." Because monuments were designed for protection rather than public use, monuments were given a fraction of the budget provided to national parks. As late as 1921, for instance, the budget for all of America's national monuments was $8,000; in 1925, it was less than $21,000; and in 1930 it was just $46,000. Funds allotted to monuments, during this period, comprised less than 1% of the NPS budget. [18] What little money was available was divvied out to monuments which received high visitation, or for capital projects intended to preserve and protect prehistoric ruins. Katmai, which one report described as "the least visited of any" of the country's 25 national monuments, and where "no protection is needed," was low on the priority list. [19] Therefore, Katmai received almost no NPS funding during the first 30 years after its founding.

Considering Katmai's visitation and remoteness, it is not surprising that Katmai received no funds or staff. Many national monuments during this period also had to skimp along on little or no funding, and most of the monuments had no full-time staff. (A custodian, either an interested local citizen or a government agent whose duties were allied with those of the monument, was often employed on an ad hoc basis.) The lack of a staff or budget at Katmai, moreover, was probably an appropriate management decision, even if funds had been available, and Katmai's resources probably suffered little for want of a staff presence. NPS officials were, however, anxious to visit the area. Their only source materials on the monument were the reports of the various NGS and USGS expeditions. In order to plan for future management and to respond to occasional queries about the monument, agency officials hoped to add to that information base.

Given the lack of a staff presence, however, the Service chose to close Katmai National Monument to the public. The monument was ostensibly closed to entry on both its lands and waters, and airplane landings were also prohibited. As might be expected from an underfunded bureaucracy, the NPS did little to publicize the prohibition against entry, and had no power to stop those who entered in violation of that ban. In addition, the agency did not announce the need for permits or licenses for those who wished legal entry into the monument. The NPS, in fact, issued no monument regulations for over thirty years after its establishment. The staff at Mount McKinley National Park, who were located some 400 miles northeast of Katmai, appear to have ignored the monument completely; not one of the Mount McKinley Superintendent's Monthly Reports issued between 1921 and 1935 mentioned Katmai National Monument. Glacier Bay National Monument, which was also under the titular jurisdiction of the Mount McKinley superintendent, was similarly ignored during this period. [20]

Because the monument lacked a staff or budget, and because NPS officials knew virtually nothing about the park except for what had been explained in the National Geographic Magazine, the agency was vulnerable to anyone who had a claim, legitimate or otherwise, to Katmai resources. In 1923, for instance, John J. Folstad petitioned the government to obtain a General Land Office permit to mine coal on the western shore of Amalik Bay, opposite Takli Island. (A permit, at that time, was necessary to extract coal from public lands.) Folstad, evidently, had been occupying and developing the site for some time, using the coal for local fuel needs. There is no record regarding how the NPS responded to this intrusion on its lands; it probably felt that it better to eliminate a small portion of the monument than to sanction mineral extraction in the monument. President Calvin Coolidge, accordingly, issued Executive Order No. 3897 on September 5, which excluded 10 acres from the monument. Coolidge's action paved the way for Folstad to gain a coal mining permit. There is no evidence, however, to suggest that such a permit was ever obtained. [21]

Prominent groups of Outside visitors began to explore Katmai in the late 1920s. In 1928 the well-known "Glacier Priest," Father Bernard Hubbard, landed along the coast northeast of the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes accompanied by a group of Santa Clara University students. They tried to cross the Aleutian Range that year but were unsuccessful in their quest. The following year, Hubbard and a coterie of students came by way of Katmai Bay and, with a film crew, successfully entered the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes by way of Katmai Pass. [22] In 1932 he made the first wintertime ascent of Mount Katmai, and in 1934 made a final exploration of the Ten Thousand Smokes area. Hubbard, who visited Alaska every summer from 1927 through the 1940s, was a geology professor, explorer, filmmaker, and lecturer; his movies about the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes were shown to audiences around the world for years afterwards. [23]

The 1931 Boundary Expansion

In 1930, Robert Griggs made his fifth National Geographic-sponsored visit to Katmai. The primary purpose of his trip was to investigate plant succession in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. As a result of his efforts he produced scientific articles which were published in the American Journal of Botany, Ecology, and the Ohio Journal of Science. [24] That fall, Ernest Walker Sawyer, an assistant to the Secretary of the Interior who specialized in Alaska matters, asked Griggs to write him a letter which elaborated on why and how the habitat of the Alaska brown bear should be protected. Griggs, who was trained as a biologist and had been particularly impressed with the bear population during his 1919 expedition, readily complied. Sawyer added a cover sheet, then mailed it to Ray Wilbur, Herbert Hoover's Secretary of the Interior. Central to both letters was a request that the National Park Service significantly enlarge Katmai National Monument. [25] Griggs, of course, had played a central role in the creation of the original monument, and Sawyer may have thought that the popular scientist would be an influential figure in the effort to create a large-scale brown bear preserve.

NPS officials, having read Griggs' accounts, were was not oblivious to the value of the Alaska Peninsula as brown bear habitat. As early as 1926, they had advertised that in addition to its geological values, "the surrounding region has some magnificent lake and mountain scenery. Water fowl and fish are abundant, as are the great Alaskan brown bears, the largest of carniverous [sic] animals." [26] And various wildlife conservation advocates, including popular author Steward Edward White, had begun pressing for an NPS bear preserve in southeastern Alaska. [27] But the Griggs-Sawyer letter was the first indication that outside parties wanted to expand Katmai's boundaries in order to protect brown bear habitat.

In his letter, Griggs admitted that the brown bear's habitat was presently not in danger. But in the future, he feared that the Kodiak bear had a bleak future. Therefore, "the Katmai National Monument is the only place in the world where the great Alaskan brown bear can be preserved for posterity." He felt that a broad spectrum of interests--Kodiak residents, Alaskan guides, and the Alaska Game Commission (AGC)--would support the monument expansion. He noted that there were no year-round residents in the proposed expansion area, that there were "no minerals of value" except for a worked-out gold placer at Cape Kubugakli, and that only one man--the trader at Kanatak, located 50 miles southwest of the existing monument--would be adversely affected by the action. He was well aware of the clam cannery at Kukak Bay, but dismissed its importance because its employees were "casual visitors." [28]

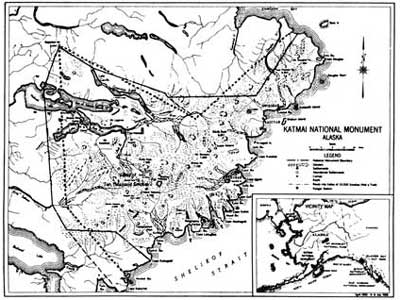

Taking care to avoid the oil-bearing tracts which surrounded Puale Bay, Griggs felt that the "low mountains and open valleys covered with tall grass and tundra" should be added to the west and southwest of the existing monument (see Map 4). A second important area was the lake region--Brooks, Naknek, Coville, and Grosvenor--which was an excellent breeding ground for waterfowl. Of particular note was the waterfall at the outlet of Brooks Lake, "where at the proper season is one of the finest exhibition of leaping salmon to be found anywhere in the world." A final area he wanted to preserve was the Aleutian Range from Kukak to Douglas. Griggs admitted that the primary value of the Aleutian Range was its scenic grandeur, not its bear habitat, and he was also quick to note the scenic advantages of all three areas. [29]

Wilderness values also were important in adding the Aleutian Range to the monument. Griggs noted that the range was

a vast mountain fastness whose very inaccessibility would almost guarantee the preservation of primeval conditions. If visitors should ever invade the other portions of the park, aboriginal conditions must inevitably be modified somewhat. But here is an area so rugged that its primitive condition can be preserved for centuries to come. All that is needed to that end is that the occasional hunters who would otherwise stray that way should be debarred and nature be allowed to take her course. [30]

The following January the NPS, in consultation with Griggs and the Interior Department, laid out the boundaries of the proposed monument expansion. The Geological Survey, when asked its opinion of the area's economic geology, offered a dim view of its suitability as parkland. The agency noted that potential oil fields existed both north and south of the present monument, and that in the vicinity of Cape Kubugakli, both gold and other economically valuable minerals had been unearthed. In the Kamishak Bay region, "a number of metallic mineral deposits" had been found; the underlying geology suggested that similar materials might exist in the area west and southwest of Cape Douglas. [31]

The Service, in response, offered to pare the size of its proposed expansion, but in mid-February, the Acting Director of the Geological Survey hardened its previous position and dissented against any boundary changes. The Survey again expressed its concern about the possibilities of oil and gold extraction, but on a broader level, the agency stated that it "is keenly interested in having as much of the region as possible kept open for free use, in order to stimulate its development." The USGS, continuing in its pessimistic vein, felt that the additional acreage was irrelevant to the original intent of the park. [32]

The NPS, not content with comments from the USGS, also solicited comments from Alaska officials, namely the Territorial Game Warden and the Regional Forester. Neither was enthusiastic about the proposal. Both felt that "the Alaska Game Commission has plenty of authority to handle the situation and that the only thing needed is adequate law enforcement." Neither thought that the NPS was in any position to provide extra staff. Both felt that the brown bear was not in any particular danger. They stated that Alaska's resources needed to be developed, not protected. [33]

The Service responded to the various comments by excluding the various oil claims surrounding Puale Bay; the new boundary lines, however, were far closer to those in Griggs's original proposal than those made in response to USGS's original criticisms. The revised boundaries, which were justified in an April 22 letter from Secretary Wilbur to President Herbert Hoover, thus ignored much of the Geological Survey's concerns about potential oil development, and similarly ignored the criticisms voiced by Alaskan officials.

Apparently emboldened by renewed pressure from bear preservation advocates, who were also pushing for a national monument on Chichagof Island in southeastern Alaska, the Secretary said that "it would appear advisable to extend the boundaries of the Katmai National Monument so that the brown bear within this monument can be protected rather than create a new monument of Chichagoff for the same purpose." Wilbur noted that the expansion, which would enlarge the monument by 1,609,600 acres, was also needed for the protection of moose; in addition, the new area "has many features valuable for educational and scientific purposes." He concluded that the proposed area "is of greater value from a educational and scientific viewpoint and for the protection of wild life than for economic development." [34] The proposed expansion also planned to reincorporate the 10-acre parcel that had been removed from the monument in 1923; John Folstad had long since lost interest in his coal claim.

Wilbur's letter was favorably received by President Hoover, who made no modifications to it. Then, on April 24, 1931, he issued Proclamation No. 1950. This document, just as the 1918 proclamation, was issued under the authority of the Antiquities Act. It gave little explanation for the expansion; it only noted that adjoining the existing monument were "additional lands on which there are located features of historical and scientific interest and for the protection of the brown bear, moose, and other wild animals." [35] (The scientific interest and wildlife values had no doubt been condensed from Secretary Wilbur's letter; the historical interest was probably derived from language in the Antiquities Act.) The affixing of Hoover's signature to the document more than doubled the size of the monument (see Appendix A). Katmai, with an acreage of 2,697,590, thus became the largest unit of the National Park Service system, almost half a million acres larger than Yellowstone National Park. For the next 47 years, Katmai would continue to hold that honor. [36]

The nation's newspapers generally ignored the president's proclamation, just as they had ignored Wilson's proclamation thirteen years earlier. News articles describing the expansion did not surface until almost a month later. What appeared in the press appears to have been a result of an orchestrated program instituted by conservationists, who were ecstatic about Hoover's proclamation. A syndicated article noted that "the creation of a sanctuary for the Alaskan brown bear, the largest and proudest race of carnivorous animals in the world is believed to have been saved from extinction." "President Hoover," it continued, "has given a reprieve to untold hundreds of wilderness aristocrats [brown bears], who had been condemned to death by the guns of sportsmen." Until now, "the bears have been easy prey to sportsmen every summer when they followed the streams down to the coast," but henceforth they "can spend their summers at the various bear seashore resorts without interference from the two-legged creatures who kill them at a great distance." Wildlife preservation advocates openly rued the extinction of grizzlies in California, and hoped to avoid a repetition of that fate. [37]

The New York Times' only response to Hoover's proclamation was a letter to the editor from Robert Sterling Yard, the well known park and wilderness advocate, who noted that:

The largest and one of our most distinguished geological monuments has become, also, by a flourish of the President's pen, one of the greatest wild life reserves in the world. Matching Belgium's national gorilla park in Africa, there is now the American brown bear park in Alaska. Thus have two of the world's most interesting and powerful wild animals each a national government protecting them from extinction.

The several scientific trips made by Dr. Robert F. Griggs of George Washington University had brought to his attention the large number of big bears in that part of the peninsula. They were not the Ursus Middendorffi of Kodiak Island, but Ursus Gyas, scarcely smaller in size, and larger than the eight or more other sub-species found elsewhere in Alaska.

In view of the warfare urged of late against the brown bear because of widespread stories of its ferocity, Dr. Griggs had been urging the National Park Service for more than a year to enlarge the Katmai National Monument as an extraordinary and sufficient refuge for this beast. ... South of it is additional wild area also abounding in bear which may be added if prospecting fails to discover expected oil wells. Besides the Alaskan brown bear the Katmai National Monument has many grizzlies. [38]

The comments emitted by Alaskans were not nearly so charitable. The Anchorage Daily Times noted that "agitation for the salvation of the brown bear, inspired by the writings of Stewart Edward White, led to the creation of the sanctuary in spite of the opposition to such action in various sections of Alaska." [39] The Seward Daily Gateway editorialized:

Secretary Wilbur of Alaska Railroad fame, and President Hoover, who said he did not believe in bureaus, both take the word of Stewart Edward White, Robert Frothingham, [Outdoor Life] Editor [John A.] McGuire and other big game hunters, that the great big brown bear of Alaska is doomed unless protected. So by official decree the Katmai National Monument is increased in area. The fumaroles will now have to move over, and make way for the brownies whom some one, or group, must be killing by the thousands.

We have said it before and say it once more that the standing army of the United States could not exterminate the bear. Hoover and Wilbur wouldn't believe that statement of course unless some committee so advised them. We're not kicking about the additional reserves because within a few years every acre will be a reserve for some darn thing. [40]

Territorial officials predictably decried the removal of such a large area from settlement and mining development, and declared that wildlife enforcement in the area was so ineffectual that the extension would do little to protect large animal populations. [41]

Naknek residents grumbled as well. The monument extension severely limited the hinterland in which legal trapping operations could take place. Trapping was a supplementary (and at times primary) source of income for many local residents; it was one of the few ways in which both white and Native residents could earn a living during the wintertime. Those who did not trap, moreover, were often in sympathy with those that did. Naknek residents, like others in Alaska, resented the taking of land because of the agitation of outside interests. Their protests were in vain; they did not, however, last long. Residents soon recognized that the NPS was unable or unwilling to police its newly-acquired territory, and activities in the area were carried on as before. Trappers did not become aware that they were in violation of monument regulations until 1936, perhaps later. [42]

Users of the Monument, 1931-1936

The expansion of the monument brought forth new plans to develop Katmai for its tourist potential. Some thought that wildlife clubs would develop the monument, because they had expressed themselves so strongly during the monument expansion process. Another potential monument developer surfaced in 1933, when the owner of a travel service wrote that he hoped to become active "promoting, showing, teaching, and selling" vacations to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. NPS Director Albright, however, openly worried that nothing should be developed before the agency established a presence. Therefore, he discouraged both proposals. [43]

A minor flow of visitors came to the monument, however, because of the advent of the air age. In 1929, Anchorage Air Transport debuted tourist flights to the area in the form of a one-day tour. For $265, the company offered to fly visitors into the still-active Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes and provide them eight hours for exploration and sightseeing. In the early 1930s Frank Dorbrandt, a pilot who flew for Anchorage-based Pacific International Airways, took several parties into the volcanic country. Robert Ellis (of Alaska-Washington Airways) and other charter operators also visited the area during the early to mid-1930s. [44] By 1940 John Walatka, a pilot for Bristol Bay Air Service, had also become familiar with the monument; a game agent praised him as one who "knows that park as few do and knows where all the cabins are located." [45]

Local residents, after April 1931, continued to use the Katmai area just as they had before the monument expansion. Trappers accounted for some of that use. Most of these men were commercial fishermen during the summer and spent the remainder of the year in cabins and on trap lines within the monument. Their use of the monument was clearly illegal, but no one from either the territorial or federal government was charged with enforcing monument regulations.

Local Native residents took part in organized traditional use activities. Those who had fled Old Savonoski in June 1912, for instance, made annual hunting pilgrimages from New Savonoski to the Savonoski River valley until the late 1930s. Throughout this period these expeditions were scarcely noticed by the authorities, but when permission was asked to continue the practice, the NPS issued a denial and the hunts came to a halt. Another group grazed reindeer in the park. Shortly after 1930, about 10,000 reindeer were brought from Nome into the Naknek River area, and a portion of that herd had grazed for awhile in the area west of Lake Coville and north of Naknek Lake. [46] The industry, however, soon declined, and by 1940 no reindeer were known to live in or near the monument. [47]

Another management headache which the NPS acquired as a result of the expansion dealt with the clam and salmon canning operations. The agency was aware of these activities; Robert Griggs, in fact, had noted in his correspondence of November 1930 that "no people live within the proposed reservation except casual visitors such as the hands of the clam cannery at Kukak Bay." What the agency did not know was that canning interests had been investing in facilities along the shore of Swikshak and Kukak bays since 1923. The canneries, however, escaped General Land Office scrutiny because their operations had not been patented. The cannery owners were probably never informed of the impending monument expansion. [48]

In February 1936, Surf Canneries called attention to its operations when it wrote Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes. A company representative noted that it owned a clam and salmon cannery at Kukak Bay, and fishing cabins, docks, and other improvements in and near Swikshak Bay; the appraised valuation of its facilities was over $90,000. The company requested a patent for four tracts of land in the two bays, and implored the secretary to remove those lands from the monument. [49]

Ickes, the Commissioner of the General Land Office, and the NPS Director Arno Cammerer all recognized the validity of the claim. Cammerer was in no mood to delete lands within the monument, so he instead proposed an executive order "so that all valid existing rights at the time of the issuance of the proclamations shall be restored." [50] Higher-ups agreed with his suggestion, and on June 15 President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Proclamation No. 2177 on their behalf. The new law stated that "it appears that it would be in the public interest" to modify the proclamations of 1918 and 1931 to make "subject to valid claims under the public-land laws affecting any lands within the aforesaid Katmai National Monument existing when the proclamations were issued and since maintained." The proclamation was intended to apply to any operation which could prove its legitimacy. As shall be seen, both cannery companies and trappers tried to take advantage of the 1936 proclamation by applying for patents. No patents, however, were ever issued to either interest. [51]

NPS officials may not have been aware of it at the time, but the land they acquired in the 1931 proclamation gave them control over an area in which another Federal agency had previously been active. Personnel from the U.S. Bureau of Fisheries, an agency within the Department of Commerce, had visited the mouth of Kidawik Creek (Brooks River) each year from 1920 through 1925 as part of their predatory fish destruction program. In 1921, they blasted the north end of Brooks Falls in order to ease the way for migrating salmon. [52] They did so in hopes of decreasing salmon mortality. But subsequent studies were not performed, so the agency had no way of knowing whether its action improved salmon reproduction.

The NPS Expresses an Interest

Although the 1931 proclamation made Katmai the largest of the National Park Service units, the monument continued to be as woefully managed as it had ever been. The superintendent at McKinley Park, Harry J. Liek, still ignored its existence, and the NPS directorate in Washington saw no need to spend money or effort for an area that few people visited and where the resources were perceived not to be in danger. When Franklin D. Roosevelt became president, he unleashed a bevy of agencies intended to help the nation's unemployed. Several of those agencies, including the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), the Civil Works Administration, the Public Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration, brought workers out to America's parks to work on trail building, improvements, reconstruction work, and similar activities. [53] But the only New Deal program that sent workers to an Alaska NPS unit was the CCC, which operated in Mount McKinley National Park from 1937 to 1939. [54] Katmai, which was remote and had no staff, was not a site for New Deal projects.

During the mid-1930s, the NPS was finally able to direct some of its energies toward Katmai. The agency had had its budget substantially increased with depression-era relief funds (its operations budget rose from $2.5 million in FY 1934 to $11.2 million in FY 1937), and its administrators were able to attend to conditions that it had long been forced to ignore. In June 1936, Arthur Demaray, who was second in command to NPS Director Arno Cammerer, came to Mount McKinley National Park on an inspection tour. Demaray was not the first high official to visit the park; Stephen Mather in 1926 and Horace Albright in 1931 had preceded him. [55] What was special about the trip was his desire to see Alaska's national monuments. By the time he had arrived at McKinley Park he had already visited Sitka and Glacier Bay. He had also planned an aerial inspection of Katmai, but inclement weather forced him to cancel his flight. [56]

Demaray's trip took place shortly after outside pressure began to be applied regarding the monument. The Alaska Game Commission warden in Dillingham, Hosee R. Sarber, visited Naknek in early 1936 and was surprised to find that "quite a number of trappers" were operating in the Naknek-Lake Grosvenor country, most of whom were unaware that they were within the monument. The most aggressive was reported to be a man named Weatherspoon [Harry Featherstone?], who had "several trapping cabins at or near the head of the Naknek Lakes." [57] Shortly afterwards, the Game Commission made five patrols along Shelikof Strait and found "several violators operating in and adjacent to the Park." Both of these reports were sent on to the NPS Director Cammerer in Washington. Frank Dufresne, the Juneau-based Executive Officer of the Alaska Game Commission, delivered much the same message when he visited the director in late March. Mount McKinley Superintendent Harry Liek, who had apparently been apprised of the situation by Dufresne, also passed on his concerns to Cammerer. Cammerer, when confronted with the problem, was caught flat-footed because he knew little about the area. All he could do, for the moment, was reiterate a sense of concern. [58]

Over the next few months, responsibility for the Katmai patrol was kicked about from one official to another. Dufresne hoped that someone on the McKinley staff might carry it out; Liek claimed lack of funds and hoped that Washington might fund the patrol. NPS officials hoped that the Alaska Game Commission could continue its patrols, but the severely understaffed agency was unwilling to do so without financial assistance from the park service. [59]

Demaray, shortly after his McKinley visit, broke the stalemate by assigning the patrol to one of Liek's rangers, the expenses to be paid for from the general national monument appropriation. Katmai was provided a $600 budget for the 1937 fiscal year. [60] The money was intended to allow a Mount McKinley ranger to "make a reconnaissance survey in Mount Katmai National Monument for the purpose of establishing a winter patrol in that area." Louis M. Corbley, who was Superintendent Liek's chief ranger, was given the Katmai assignment in October 1936. He was to arrive at Katmai by November 10 and remain for a minimum of five months, enough for an entire trapping season. A maritime strike, however, quashed his immediate plans. He was not able to visit Katmai until the following spring. [61]

Corbley spent most of June 1937 away from Mount McKinley. He sailed around the peninsula to Naknek, then chartered a boat to go up the Naknek River. But the boat was unable to overcome the rapids, so he returned to Naknek and chartered a flight to Lake Coville, Lake Grosvenor, and the upper end of Naknek Lake. Corbley later flew over the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. He landed just twice, at "Old Village" (probably Savonoski) and at Brooks Lake, where he spent a few hours. His time being limited, he then returned to McKinley Park. He gave no account of his one-day excursion save a brief trip report, which included no information about either the structures or the people he encountered. [62]

The visit was the first that any National Park Service official had made to Katmai since it had been established 19 years earlier. Information, even if brief and sketchy, had been compiled. So, to use Gruening's analogy, the agency's management rose from that of "total neglect" to "flagrant neglect." But Corbley, unfortunately, left the Mount McKinley staff within the next few years. The agency made no attempt to make its patrol an annual event, and its previous inclusion in the Mount McKinley budget was eliminated.

In the meantime, the Bureau of Fisheries, which had performed some rudimentary "improvement" work by blasting out the north end of Brooks Falls back in 1921, applied to make its presence more permanent. In response to concern about Japanese offshore fishing in the Bristol Bay area, Congress directed the bureau to investigate the bay's salmon resources. The plan, conceived in 1938, called for a data collection effort by both offshore and land-based teams. Naknek River, one of five major study targets, received a three man team in 1939, which made a survey of the river system's major spawning grounds. The following year the Bureau established a weir and cabin near the outlet to Brooks Lake. As noted in Chapter 8, they were to maintain their presence at the site for decades to come. [63]

Trappers and the Kinsley Investigation

Reports of Katmai trapping violations, first voiced in early 1936, reached a sufficient crescendo by late 1937 that NPS officials were forced, once again, to pay attention to the monument. [64] The NPS had no staff to deal with the problem, but they hoped to gain some assistance from cooperating agencies.

The NPS soon found that few in the local area had much sympathy with them. Residents had not been consulted about the 1931 expansion, but most had tacitly accepted the enlarged monument as long as the regulations had not been enforced. [65] The first hint of enforcement activity, however, brought resistance. Two of the trappers, Stephen M. Scott and John Monsen, protested that they had a legal right to use the monument's lands. [66] In addition, several other trappers headed a petition of 53 residents from the Naknek vicinity that implored Alaska Delegate Anthony J. Dimond to "help us in any way possible" to relax the enforcement of monument regulations. [67]

The NPS responded to the protests in two ways. First, it squelched any ideas that the agency would willingly give up on Katmai. Also, it asked the General Land Office to find out which trappers had valid land claims, based on the 1936 presidential proclamation. The GLO undertook the task in January 1938, and assigned A. C. Kinsley, a special agent from the Department of the Interior, to investigate.

Throughout this period, both the GLO and the NPS told the trappers that their claims were being investigated; they did not try to evict any trappers from their cabins. But Stephen M. Scott, speaking for four other trappers beside himself, complained to Anthony Dimond that "The Game Warden and another gentleman of the Forestry Department have issued [an] order to get out without so much as by your leave" sometime during 1937. [68] The NPS, when told of Scott's charge, had no knowledge of such an eviction, and representatives from the Alaska Game Commission, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Alaska Road Commission all told the NPS that no one in their agencies had tried to evict anyone. [69]

Kinsley spent the next year investigating the validity of the trappers' claims. He visited the Naknek area in July 1938, tried to contact each of the claimants, and submitted his recommendations in the GLO Commissioner in January 1939. The GLO, in turn, forwarded them to Cammerer in May. The GLO concluded that four trappers--Stephen M. Scott, John Hartzell, Verner Eckman, and John Monsen--were already established in the area before the 1931 monument expansion. Therefore, as a result of the 1936 proclamation which validated existing rights, the four had "a possibility of their claims being valid" even though they were now located on monument land. [70] Roy Fure, another trapper, could not be contacted during the initial investigation. During the summer of 1939, however, his claim of residency in the area prior to 1931 was also substantiated. [71] The GLO found that four other trappers--Richard Mitchell, Paul Chukan, Gunnar Berggren, and Sigurd Lundgren--had begun trapping after 1931 and thus had no valid claims to their property. [72] The GLO report did not investigate the claim of other monument trappers, including John "Frenchy" Fournier, Martin Monsen, Alfred Cooper, and a man named Karvonen. These people, presumably, began trapping after 1931; their claims, at any rate, were never investigated. [73]

The GLO concluded the investigation by notifying Mitchell, Chukan, Berggren and Lundgren that they were trespassers and should leave the monument if they had not already done so. (Chukan and Berggren protested the decision, but were ultimately overruled.) [74] Scott, Hartzell, Eckman, Monsen, and Fure were free to continue residing in the monument. Monument regulations, however, forbade them to trap. Those spotted in the monument with trapping gear or hides were subject to arrest--if authorities were willing to expend the effort to track them down. As time would prove, the legal process prodded some to abandon their trap lines, but others continued to evade monument regulations for years afterward.

During the investigation, several trappers had contended that they were unaware that they had been operating in the monument. The boundaries as set forth in the 1931 proclamation, moreover, did not easily correspond with identifiable physical features. The NPS, therefore, tried to get the GLO to survey the monument. At a minimum, they hoped to survey the northern and western boundaries, where trapping activity was highest. The first such request was made in early 1937, and was repeated in the spring of 1939, 1940, and 1941. [75] NPS officials recognized that the man to conduct such a survey would be George A. Parks, GLO's District Cadastral Engineer in Juneau. The engineer repeatedly promised to survey the monument's western boundary. But Parks, for whatever reason, was unable to get a surveying crew out to Katmai. [76]

Carson and Been Visit the Monument

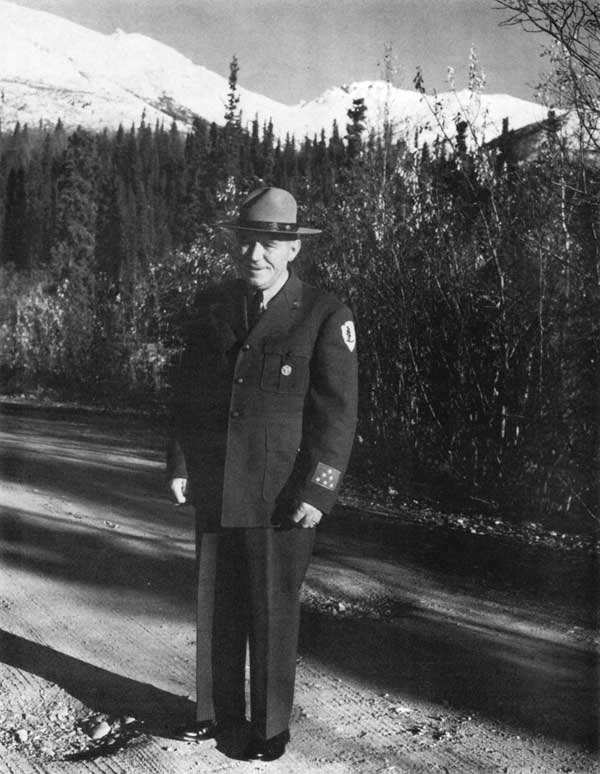

During the adjudication process of 1938-39, officials at Mount McKinley National Park were acutely aware that all of Alaska's NPS units were woefully understaffed. Officials at the Alaska Game Commission, asked to enforce the game laws throughout the territory, felt likewise. Both agencies soon realized that the best way to deal with poaching and similar problems was to share enforcement responsibilities. To help the NPS in southwest Alaska, the Alaska Game Commission asked its Dillingham wildlife agent, Carlos M. Carson, to keep tabs on Katmai National Monument. In December 1939, the NPS reciprocated by naming the various Mount McKinley rangers to be Deputy Game Wardens of the Alaska Game Commission. The cooperative effort may well have been spearheaded by Mount McKinley superintendent Frank T. Been, who replaced Liek in June 1939. [77]

In January 1940, Superintendent Been represented the NPS in Anchorage at a meeting of the Alaska Game Commission. Shortly thereafter, he was told that "although it was not determined from inspections, it was learned through reliable sources that trapping is being done at Katmai National Monument, just as though there was no national park area there." Carlos M. Carson, the AGC warden in Dillingham, decided to see for himself on March 20. He and pilot Grenold Collins flew into the monument, and at the eastern end of Naknek Lake, Carson found three trappers--Alfred Cooper, Martin Monsen, and John Monsen--and apprehended them for taking fur in the monument. Been soon heard about it, and he gratefully approved the game commission's request to prosecute the violators. [78]

Carson, in an April 7 letter, told Been that the area was "an animal paradise" in which "trapping is done openly and widely." The superintendent, clearly alarmed at the news, wired the NPS director with the news and requested funds "to patrol the monument during times of the year when violations are most likely to occur." [79]

Carson apparently returned to the monument in May, apprehended several more trappers, and confiscated fur from illegal operations in the monument. Been, meanwhile, told his Washington superiors that the level of resource management at Katmai was clearly inadequate. Having been granted funds to visit, he promised a full report on trapping activities. [80]

Superintendent Been spent most of the summer of 1940 in the field; during September, he traveled around Katmai National Monument accompanied by Victor Cahalane, a biologist with the U.S. Biological Survey. [81] The two flew from Anchorage to Naknek; they then took a short flight that led to the lower end of Brooks Lake, to the Savonoski River and on to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. They returned to Naknek by way of lakes Grosvenor and Coville. On September 4, they headed out on a boat trip which took them up the Naknek River and on to Brooks River, and on to a trapper's cabin near the mouth of the Savonoski River. They also boated around Brooks Lake in search of trapping activity, and hiked from the mouth of the Ukak River into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. On their way out of the monument, Cahalane and Been flew east over the Ukak River valley one last time, then went over Katmai Crater and down to Kukak Bay before continuing on to Kodiak. The two then separated, Been heading to Anchorage on his way back to McKinley Park. [82]

Been's report on the trip showed that the monument was far more scenic than he had been led to believe. Before he left, he had received "rather definitely unfavorable comments about the monument from men occupying important positions." [83] But his narrative was replete with descriptions of the area's beauty and bounteous wildlife, and he emerged from the trip "strongly inclined toward its retention in the national park system," noting that "the monument abounds in natural wonders and grandeur." He recognized the tourist potential of the area, although he felt that its remoteness precluded it from becoming a tourist center for many years. [84]

In addition, Been was pleased to discover that he found no signs of active trapping. On the contrary, he saw several stripped cabins and abandoned caches. The trappers, hounded by Carson, had apparently moved out of the park. [85] For the time being at least, Been was satisfied that monument-based trapping had been squelched on the Bristol Bay side of the Aleutian Range.

The 1942 Boundary Expansion

At the end of their trip to Katmai, Been and Cahalane spoke to the local Alaska Game Commission agent in Kodiak, Jack Benson. The agent was aware that trapping was taking place on the coast of the monument; he even knew the locations of several cabins. But he had no boat assigned to him worthy of the Shelikof Strait crossing, and he had not yet been asked to include the Katmai coast in his patrols. Been gave him permission to patrol that area and to act on behalf of the NPS when so doing. [86]

Cahalane remained on Kodiak Island for the next several days. He accompanied Benson on his patrols, and traveled with him over to the Katmai coast. He did not like what he saw. Two months later, he sent his concerns on to Ben H. Thompson, head of the NPS Land Planning Division. He noted that

it is perfectly feasible for poachers to base their operations on any one of the numerous islands in the bays of the Shelikof Strait section while they may trap on the mainland of the monument with greatly enhanced chances of escaping detection.

He told Thompson that the best solution to the trapping problem was to extend the existing boundaries to include the various islands in the coastal area. He noted that an added benefit of including the islands was to prevent the possibility of any fox-farming operations being started. But Kiukpalik Island, he noted, had had a fox farm for a number of years; therefore, he urged that the island be excluded from any proposed additions to the park. [87]

Superintendent Been wrote a concurring note to the NPS Director in mid-December. He suggested that the boundary be extended two miles from the shore line, and that "Any islands touching this line should be included." Based on the maps he had available, he felt that the monument would include just three new islands: Shaw Island, north of Cape Douglas; Ninagiak Island in Hallo Bay; and Takli Island, at the entrance to Geographic Harbor. [88] He chose those islands because they were the only coastal islands which, in his opinion, were not already claimed as a fox farm and were sufficiently distant from the coast that a fox farm might logically be located there. [89]

Been, meanwhile, asked authorities in Alaska to comment on the proposed monument addition. Neither the District Land Office or the District Cadastral Engineer saw any difficulties in such an action. Frank Dufresne, who worked for the Alaska Game Commission in Juneau, thought that a boundary extension was the best way to ward off the illegal taking of game and fur in the monument, but Jack Benson, the AGC agent in Kodiak, thought that the problem could be managed under existing arrangements. Alaska Game Commissioner Andy Simons likewise opposed the addition of the islands, citing possible impact on the fishing industry and negative reaction from local residents. [90]

On January 30, 1941, Been sent copies of those comments to the NPS director. He noted that "Examination of the opinions and comments contained in these letters shows no substantial reason for opposing the Monument extension; the doubts raised are from exaggerated impressions of Park Service protection restrictions." He did acknowledge possible negative impacts to the clam fishery. [91]

To evaluate the legal ramifications of the boundary extension, the GLO Commissioner called in A. C. Kinsley one more time, in order to investigate the validity of trapping operations along the Shelikof Strait coastline. [92] His report on the area, completed in August 1941, revealed that only two men had an existing fur farm lease: Earl L. Butler of Kodiak, who had initiated a 10-year lease on Kiukpalik Island in 1937, and John A. Smith, also of Kodiak, who began a 5-year lease of Takli Island in 1939. Kinsley noted that "Mr. Butler's success with this island has been small." Smith, he noted, had likewise encountered difficulty with his Takli Island lease. He had failed to stock the island as demanded by the lease, and had been guilty of game violations as well. No other people would be affected by the inclusion of any of the offshore islands in the monument. [93]

Based on Kinsley's report, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes in November 1941 recommended a five mile boundary extension and noted that "it would in no way be harmful to potential business enterprises in that general part of Alaska." The following January, Ickes sent a draft proclamation to President Roosevelt, who circulated it to various executive departments. [94] On August 4, Roosevelt signed Proclamation No. 2564, which formally moved the boundary east to include "all islands in Cook Inlet and Shelikof Strait in front of and within five miles of the Katmai National Monument." [95] The proclamation included about twenty offshore islands, including Takli and Kiukpalik. Takli alone had an area of about 450 acres; there were slightly more than 3,000 acres on all of the newly added islands. [96]

The new proclamation, combined with those given in 1918 and 1931, gave Katmai an area of almost 2.7 million acres. But without a staff or budget, the National Park Service remained powerless to manage the unit. Throughout the 1940s, as noted below, there would be repeated attempts to establish active management authority over the expanse. The same period would witness an increasing number of problems at the park, most of which were either caused or exacerbated by the lack of a management presence.

Attempts to Establish a Management Presence

The recognition that trapping was taking place throughout the monument convinced Been that Katmai needed on-site management even before his September 1940 inspection trip. He sympathized with the anger that many Alaskans had no doubt vented to him when he wrote, "It is hoped that funds will be provided so that the NPS will be able to administer the areas rather than have them continue as illustrations of apparent mismanagement or service indifference." He felt that in order to patrol the monument, "a custodian should be assigned at once--preferably two who can travel together as there are many hazards." [97]

To implement his suggestion, he requested a $14,300 budget for Katmai in May 1940--enough for two staff, a power boat and travel expenses. But in November the NPS Director informed him that his request had been slashed to $3000, sufficient only for one Naknek-based permanent ranger, supplies, and travel expenses. And in early 1941 he was told that "we shall be fortunate if we get an appropriation for administration and maintenance." His request for a patrol boat was denied. [98] Been responded by submitting a fiscal year 1943 budget for $20,293. It called for both chief ranger and ranger naturalist positions. Also included was a provision for purchase of a patrol boat and a 16-member dog team, along with needed travel, supplies, and ancillary items. [99]

Joseph S. Dixon, a biologist for the Fish and Wildlife Service (F&WS), concurred with the need for Been's request. Herbert Maier, the Acting Regional Director in San Francisco, was also supportive that a presence be established at Katmai, noting that "it is difficult for us to see how any area, particularly one of such an enormous size, can function without any resident personnel." [100] But the national office slashed Been's budget to just $4,000: $2,000 to employ a permanent ranger, $1000 for the purchase of a dog team and radio, $400 for a superintendent's trip to the park, and $600 for miscellaneous expenses. [101] Congress ignored the Service's Katmai funding request.

In January 1942, Been submitted 21 Project Construction Program (PCP) proposal forms for projects at Katmai. The proposals were requested by the regional director, and afforded a means of recording information and suggestions of one of the very few Service employees who had any first-hand knowledge of the monument. The request for project proposals, therefore, did not indicate a renewed interest in Alaska's monuments, and a actual establishment of a construction program was considered "most unlikely." [102] Ten of the PCP proposals called for the construction of remote shelter cabins. He also called for the construction of a monument headquarters and visitor center in Geographic Harbor, unspecified developments at Brooks River and Brooks Lake, and a series of roads and trails. Finally, he recommended a $25,000 project to restore Old Savonoski by reconstructing its buildings.

Been gave considerable thought to the location of the monument headquarters. He chose Geographic Harbor, in part, "because of its proximity to travel from the states," and he also liked the local scenery, the ample fresh water, its protection from winds and its location vis-à-vis the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. He noted, however, that

there is still some justification for having Naknek as the monument base until funds are provided for its development. Naknek provides a place of residence for the first personnel and is accessible to the part of the monument in which most of the violations are occurring from hunting and trapping. Out from Naknek, the development at Brooks Lake and Brooks River can be prepared and many of the proposed shelter cabins constructed. [103]

Been had visited Naknek but not Geographic Harbor; his choice of the latter site, therefore, was probably based on a 1940 visit by NPS biologist Victor Cahalane (with whom he had traveled that summer), combined with descriptions provided by the 1919 National Geographic Society expedition. [104]

Regional office staff had mixed feelings toward the proposals. The cabins, for instance, were criticized because they would "provide shelter, indiscriminately, to 'friend or foe' of the park." Regarding the Savonoski project, they thought it more appropriate that the village should first be measured and have drawings made before a restoration was attempted. Another noted that the Savonoski work would "require questionable methods and after the work is done considerable annual maintaining will have to be done to prevent loss of work done." Agency officials generally supported the other PCPs. The regional office recommended all but the Savonoski project to the directorate in Washington, but none of the other 20 projects were funded. The U.S. government, now fully involved in World War II, was not about to expend funds for recreational or interpretive facilities in an Alaskan national monument. [105]

The Region Four office apparently used Been's personal knowledge of the monument, combined with the information contained in his project construction proposals, to write Katmai's first master plan. The plan, part of an agency-wide effort to get ready for the expected tourist boom that was sure to follow the war, was written in the summer of 1942, and Been approved it on September 10. Almost two years later, on June 29, 1944, it received Washington's approval when it was signed by Assistant Director Hillory A. Tolson. What the plan said is a matter of conjecture. Only two copies of the plan were produced, neither of which are known to exist today. No evidence suggests that the plan was ever used as a context for future monument decision-making. [106]

Been, who had a personal interest in the monument as a result of his month-long stay and his role in the 1942 monument expansion, left the NPS to join the army in May 1943. His successor, acting superintendent Grant Pearson, had been a McKinley ranger since the 1920s and had little initial interest in Katmai. Because the war brought restrictions on both travel and materials usage, few plans appeared for monument development.

Wartime Usage of the Monument

The onset of the war, however, resulted in a sharp increase in use in and around the monument. In 1941, the U.S. Army Air Service established Naknek Air Base, [107] and commercial salmon fishing stayed active throughout the territory. The growing popularity of travel by small planes, combined with the presence of the nearby air base and Bristol Bay salmon canneries, made the drainages of the upper Naknek basin increasingly attractive to recreational fishermen. Military and construction personnel at the air base flew to Brooks River, the Bay of Islands and other fishing spots and reportedly pulled "thousands upon thousands of trout" from the water. Pilots for the Ray Petersen Flying Service, Bristol Bay Flying Service and Woodley Airways flew an increasing number of cannery personnel into the lakes and rivers of the upper Naknek drainage. [108] They were soon joined by Bud Branham and other pilots familiar with southwestern Alaska. The NPS, whose nearest personnel were stationed 300 miles away, was powerless to stop the onslaught. [109]

To cater to military personnel who wanted to fish closer to the base, the Army Air Service established two nearby rest and recreation camps. Rapids Camp (also called Annex No. 1) was located at the foot of the Naknek River Rapids, five miles southeast of the base, while Lake Camp (Annex No. 2) was located at the west end of Naknek Lake, seven miles to the east. Naknek River and the western end of the lake, therefore, were also subject to heavy fishing pressure for the duration of the war. Neither camp was within the monument, but boundary changes in 1969 and 1978 would bring them within the sphere of NPS influence. [110] (See Chapter 5.)

Pearson and Kuehl Visit the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes

Pearson probably knew little about the extent of illegal fishing that took place at Katmai during the war. But in August 1945, he received a request that promised legal use of the monument's fishery. The U.S. Naval Operating Base in Kodiak sought permission to establish a fishing camp in the monument near Brooks Lake. The camp, consisting of two 16' x 30' Yakutat huts, was to be located "one-half mile east of Brooks Falls and one mile east of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Biological Station," at or near the site of present-day Brooks Camp. [111]

Perhaps in response to the Navy's request, Pearson visited Katmai to take a closer look. On August 17 he left McKinley Park; shortly afterwards, he and Alfred C. Kuehl flew from Elmendorf Field to Naknek Air Base on an Air Force plane, passing over the Mt. Mageik and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes en route. [112] Flying back over Naknek Lake the next day, Pearson "was astonished to see that two-thirds of Katmai Monument didn't seem to have been affected at all by the eruption." The two completed their explorations by hiking up into the Valley, returning to wait for their plane, and heading out of the monument.

Pearson was obviously impressed by what he saw. He exclaimed that "This should make a hit with tourists if we could ever get 'em in here." He reported that an airfield could be built in the valley, and even suggested that a road could be built there from Naknek. Kuehl, by comparison, was nonplussed by it all. Though he was convinced that Katmai was worthy of NPS management, he felt that "the scenic values of the monument are not particularly outstanding when compared with other scenic regions of Alaska," and that the "lakes within the area are large but lacking in a magnificent adjacent setting." [113]

The two also differed on how realistic it would be to attract tourists to the remote location. The ebullient, can-do Pearson noted that the two began to "scheme out ways and means to bring in visitors and take care of them." [114] They may even have made tentative plans for a tourist lodge, boat docks, trails, patrol cabins and administrative sites. But Kuehl, in his trip report, felt that Katmai was so inaccessible that "visitor use, if any, will be extremely limited" and that "Only the curious wealthy sportsman and the scientifically inclined able to stand the expeditionary expense will be likely to view the area." [115]

Three weeks after Pearson returned to the park, he received a visit from Commander Jack Benson about the proposed Brooks Lake camp. [116] Benson said that it was the Navy's plan to allow its personnel to spend short furloughs there. Pearson liked the Navy's idea, and sent his approval to his Washington superiors. But in mid-October, the Navy notified Pearson that its plans had changed. It now proposed to build its main camp "near the head of the Naknek River, just northwest of Naknek Lake" and thus near the Lake Camp facility. The superintendent was told that the Navy would later build an auxiliary camp at the Brooks Lake site, but he heard no more from them about it. [117]

Katmai Management Issues, 1945-1948

During the latter half of the 1940s, the NPS had a host of resource management issues with which it had to grapple. A clam cannery on Kukak Bay demanded the right to operate. Similarly, local interests sought the right to mine pumice and volcanic ash within the monument, and additional prospecting was taking place for hard rock minerals. Each of these operations were technically illegal, but had the support of Alaska's delegate to Congress and Alaskan development interests. (Clamming and mining are covered in greater detail in chapters 8 and 11, respectively.) Trapping became an issue once again, and portions of the monument became so heavily fished that officials began to worry that overfishing might deplete the fish stocks.

But the government seemed no more inclined to provide basic funding than it had in previous years. Much of its lack of interest was based on its low priority to NPS officials. Ever since the days of Stephen Mather, the NPS had gained popularity and legitimacy through publicity and by encouraging appropriate tourist development. This policy worked well for most areas, but it put Alaskan parklands at a great disadvantage. During the postwar period the agency was particularly sensitive to the parks as recreational destinations. Katmai, which had recorded only 32 official visits in the 30 years after its establishment, was perceived to have little potential for visitation because of its remoteness and inaccessibility. [118] By September 1945, the agency had formulated development plans for Mount McKinley and Glacier Bay, and a plan for Sitka was in the works. But regarding Katmai and Old Kasaan, NPS Director Newton Drury admitted that "we are almost totally lacking in information upon which to base even tentative plans for the[ir] future development." [119]

Little facilities development took place in any of Alaska's national park units during the 1940s. Year after year the Mount McKinley superintendent proposed a budget which included development plans for most Alaskan park units; just as predictably, the proposals went unfunded. Sometimes it was the NPS directorate in Washington that wielded the budget ax; more often the culprit was a Congressional committee. As funds subsumed in the war effort were freed up for alternative uses and as Alaskan interests became more persistent in their demands, increasing headway was made in the budgetary process. But no action was forthcoming before the end of the decade. [120]

In January 1947, Frank Been returned from the army and resumed his duties as superintendent at Mount McKinley. Not long afterward, Katmai issues crossed his desk when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service informed him that trapping had resumed in the monument. [121] Carlos Carson, the Fish and Wildlife Service agent in Dillingham, had discovered four men living and trapping inside its boundaries. The four, one of whom was Stephen M. Scott, were quickly arrested and hauled out for a commissioner's hearing. [122]

Been, through Carson, learned that the local trappers were pleading innocent to trapping charges because they claimed ignorance of the boundary location. To mitigate the problem, he contacted George Parks, the Regional Cadastral Engineer for the Bureau of Land Management (formerly the GLO), regarding a possible survey of the northern and western boundary. Parks considered the idea, but he was no more able to undertake such a survey than he had been during the years preceding World War II. [123] Lacking a survey, Been relied on the Fish and Wildlife Service agents to contact each trapper and explain the various boundary locations. [124]

The following year, Carson found much the same activity going on. He told Been that he had discovered a trapper's cabin at the mouth of Headwaters Creek, at the southwest end of Brooks Lake. Kirk Adkinson, who lived there, was tried but released; Henry Nelson, who claimed a residence just outside the monument, was declared innocent of any wrongdoing. Both had been active in the monument the year before. Carson also found "fresh evidence of others using the cabins within the park and on the bank of the upper Naknek Lake," and was told that "the army [Air Force] boys go into this park and kill moose all winter." Finally, he heard that one local trapper, Jim Marlette, was using a small plane and had "a sizable illegal beaver cache in there." Recognizing that he was fighting a losing battle, he declared that "Something should be done and quickly." He called for the installation of on-site staff, noting that "if there is not a Ranger in there to protect things it might as well be turned out to the public." [125]

Been and Carson also knew that fishing pressure was steadily increasing in the monument. There was a temporary lull in sport fishing after World War II, but Northern Consolidated Airlines (NCA), along with independent pilot Bud Branham, took groups of fishermen into the area as early as 1947. The three most popular areas were the waters surrounding present-day Brooks Camp, Grosvenor Camp, and Lake Camp; Brooks River became so popular that the Standard Oil Company of California sponsored a color film, in the spring of 1948, on the stream's rainbow trout fishing. [126]

During this period, fishing in Katmai was illegal--aircraft landings were against the law except on official government business--but officials winked at the activity because it had an insignificant impact, in most places, on area fish stocks. Fishing regulations specified that no more than ten fish could be caught per day and that the total catch be limited to twenty fish, and in most cases (so far as is known) fishermen followed those regulations. [127] Along Brooks River, however, the fishery began to be abused. As Ray Petersen remembered the situation, "poaching was rampant and the trout were caught with gobs of salmon eggs on giant Colorado spinners and hooks." [128] By the summer of 1948, Fish and Wildlife Service representatives stationed at Brooks Lake noted "quite definitely that the rainbow trout have decreased as the result of the popularity to air borne sportsmen." [129]

Carlos Carson, the local fish and wildlife agent, was well aware of the growing abuses being perpetrated in the monument. Fortunately, his March 1948 plea for a ranger did not fall on deaf ears. Been reacted by offering him the position of Deputy Park Ranger, which gave him "complete authority to act for the National Park Service." [130] He then sent a copy of the letter to the Washington office. Hillory Tolson, an NPS Assistant Director, responded by suggesting a presence by both NPS and F&WS personnel. He requested the Regional Director, Owen A. Tomlinson, to send him a budget estimate for NPS patrols in the monument in cooperation with Fish and Wildlife agents. He also suggested that Grant Pearson, then at Sitka National Monument, should be sent on one or more trips to Katmai to check on fishing activities and the possible careless use of firearms. The naming of George Kelez, a Fish and Wildlife agent stationed at Brooks Lake, as a Deputy Park Ranger, was an additional action intended to establish an enforcement presence. Kelez, however, was soon elevated to a supervisory position and spent little time in the monument. [131] That August, regional office staff also considered the appointment of F&WS agents at Kodiak as deputy park rangers. [132]