|

Katmai

Tourism in Katmai Country |

|

CHAPTER 2:

ESTABLISHING THE NORTHERN CONSOLIDATION CONCESSION

During the late 1940s Ray Petersen, President of Northern Consolidated Airlines, brought an increasing number of fishermen into the Katmai country. His business activities brought him into increasing contact with Washington political figures, and several suggested that he attempt to develop camps in the Katmai country. He approached NPS officials with that idea in late 1949; the agency readily accepted his proposal, and the two signed a concessions permit in March 1950. NCA spent the next several months feverishly assembling its camps. The National Park Service responded to Petersen's move by establishing its own camp nearby.

Creation of the Concession Permit

The Katmai country was "discovered" by fishermen during World War II, and the cessation of hostilities brought new popularity to the region. Because no National Park Service personnel were stationed there the monument was still officially closed, and Federal regulations also prohibited airplanes from landing there. [1] Despite those regulations, however, a growing number of visitors, mainly fishermen, traveled into the monument. The influx numbered several hundred, but the exact number was unknown. [2]

Northern Consolidated Airlines (NCA), along with independent pilot Bud Branham, took excursions and charter parties to "Naknek and vicinity" for sport fishing as early as 1947. In 1948 Edwin Seiler, from King Salmon, began fishing Grosvenor River, the short stream connecting Coville and Grosvenor lakes, because it offered "the best Dolly Varden fishing in the area." By the spring of 1948 the Standard Oil Company of California had sponsored a color film which depicted the advantages of rainbow fishing on Brooks River. [3] Another factor pointing to the growing popularity of the area was Kokhanok Lodge, built on Iliamna Lake in 1949. Kokhanok, built by Bud Branham, was the first sportsman's lodge in southwestern Alaska, and before long the owner was flying fishermen to Brooks and other Katmai points. [4]

During the late 1940s, NPS officials continued to receive reports from Fish and Wildlife Service officials about the degradation of area resources. Officially, hunting and trapping were prohibited within the monument. Fishing regulations specified that no more than ten fish could be caught per day and that the total catch be limited to twenty fish. [5] The ugly reality, however, was that hunting and trapping violations were increasing, and the fish resource was being abused to the point where "poaching was rampant and the trout were caught with gobs of salmon eggs on giant Colorado spinners and hooks." [6] By the summer of 1948, Fish and Wildlife Service representatives stationed at Brooks Lake noted "quite definitely that the rainbow trout have decreased as the result of the popularity to air borne sportsmen." [7]

During the same period, Alaskan interests began to covet other monument resources. During World War II, the NPS had allowed a company to harvest clams along the Pacific coast as an emergency food source. But in 1946, an application to carry on much the same uses was denied, and local residents howled in protest. In subsequent years came demands to extract pumice from the Kukak area, along the Pacific coast, and to allow hunting in the monument. One and all, it appeared, demanded that the monument be reduced or abolished. [8] NPS officials reacted to the pressure by seeking methods by which visitation to the area could be encouraged while simultaneously protecting area resources.

Ray Petersen, president of the newly-formed Northern Consolidated Airlines, played a major role in alerting others of the fisheries resources of the Katmai country. In conjunction with plans to build the present Anchorage International Airport, he befriended Lt. Gen. Nathan Twining, head of the Alaska Air Command. He also made frequent visits to Washington, D.C., in connection with route certification and related matters, where he met leaders such as Leonard Wood Hall, Congressman from New York; Judge J. Russell Sprague, another New York political figure; and Republican party stalwart Herbert Brownell. He invited these three to the Katmai area shortly after the 1948 Republican convention. Sprague and Brownell were taking a particularly well-deserved rest, having played major roles during the convention. [9]

As official and recreational trips to Katmai increased, Petersen and others recognized the desirability of establishing base camps. General Twining, during a Washington visit in the winter of 1948-49, may have been the first to suggest such an idea. [10] Other officials encouraged Petersen to go a step further and apply for a franchise for lodge operations in Katmai. They did so for several reasons: 1) bad weather, which often caused flights to be delayed, made independent tent camping uncomfortable; 2) existing tent campers were interfering with operations at the Brooks Lake Fisheries Station; and 3) problems with littering and overfishing were arising on an increasing basis. NPS officials, for their part, recognized that a concession operation offered one of the most effective ways to combine increased visitation and park protection. [11]

Petersen was initially unconvinced that such an operation would be economically viable, and he had additional doubts that a fishing camp was an appropriate or even legal adjunct to an airline operation. [12] By the winter of 1949-1950, however, he was ready to consider the project, primarily because he believed tourists were a necessary adjunct to regional growth in southwest Alaska. Petersen, head of a cadre of NCA managers characterized as "young and desperately earnest empire builders," recognized that "tourists are the biggest thing that Alaska can develop," and further observed that "we are counting on them as our long-range, steady customers. We feel that people, more than goods, spell success for us." [13]

Toward the development of that market, the company inaugurated a sales, publicity, and advertising campaign in late 1949. Petersen intended that the linchpin of the campaign, if it could be manifested, would be "the mysterious beauties and volcanic wonders of Katmai and the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, and the world-renowned angling to be had in that area." The company also had its sights set on developing tours in other parts of its route network, and to that end it purchased a series of hotels or roadhouses at McGrath, Platinum, and Bethel. [14]

On December 14, 1949, Petersen met with National Park Service and Bureau of Land Management officials in Washington and laid out his plans. Although Petersen was still reluctant to drag his company into the lodging business, an observer noted that "they [NCA] found it necessary to do so to get the facilities started. [Petersen's] intention is eventually to sublet them or permit their operation by private individuals if this can be arranged." [15]

His proposal called for the establishment of four small fishing camps. A camp "near Brooks Lake" and another near Lake Coville were planned on land located within Katmai National Monument. The two other proposed camps, at "Nanwhyanuke Lake" and Battle Lake, were on Bureau of Land Management land. [16] Petersen had personally chosen the general locations for each camp, considering them the best fishing spots in the Katmai country. [17] In order to create a suitable environment for his guests, Petersen had relatively modest plans for the camps. An observer at the meeting, Charles Richey, noted that

the intention is to have a tent frame arrangement of two or three tents, where overnight facilities can be provided for six or seven guests. Mr. Peterson [sic] mentioned that the company wants to keep these parties small and to sort of feel its way. As I understand it, the company will provide a camp tender who will cook the meals and take care of the activities. [18]

Petersen found a receptive audience. Richey noted that the Assistant Secretary of the Interior

is very enthusiastic, and ... he intends to do everything possible, within the Department's limitations, to help it along. I told the group that I was sure the Service would regard the proposal sympathetically. As we have no facilities there to care for legitimate visitors, I am inclined to think that this type of permit may be helpful to us in Katmai. [19]

Petersen then proceeded to finalize his plans.

The project being proposed was something new in the annals of the National Park Service. National parks had been dealing with concessioners since the establishment of Yellowstone in 1872, and over the years had contracted with owners of hotels, gift shops, transportation companies, filling stations and other businesses. By 1950, there were several hundred concessions active in the various NPS units. Some of those concessioners operated airplanes in the parks. Never before, however, had the NPS leased a concession operation to a company whose primary business was the intercity transportation of passengers and freight. It was also the first time that the NPS had depended upon an airline as the primary means of access to one of its units. The arrangement worked because the camps were some of the least accessible facilities in the national park system. [20]

Because the Service was unable to consider staffing the monument, it proposed to allow an extraordinary degree of autonomy to the concessioner. For instance, there were no initial provisions for either resident or seasonal NPS staff in the area. To fill in the void, one NPS official suggested that Petersen might play a role in protection, remarking that

I think it is possible that we could arrange through this permit to get a certain amount of protection in the national monument area through the permittee. At least we could request that the permittee's representatives report any types of adverse use and be helpful to Service personnel in looking over and studying the area. [21]

On January 21, 1950, Petersen formally wrote for permission to operate two camps in the monument for a two-year period. Citing the need to conserve park resources, as well as the need to recoup capital outlays, Petersen requested an exclusive concession. He gave additional details about his proposed camps. The base camp, which by now had been located at the mouth of the Brooks River, had increased in scope; it was to consist of "framed tents, sufficient to house and feed twenty to thirty people." He also applied to operate another camp, to be "set up on the stream which connects Coville and Grosvenor Lakes." Plans for an expanded camp system outside the monument were not forgotten. Petersen made arrangements for a meeting the following month in which he "would like to arrange for lease or purchase of three sites ... for the construction of camps." The fifth camp, although unspecified in his letter, was Kulik Camp, located on the north bank of Kulik River at the outflow of Kulik Lake. [22]

|

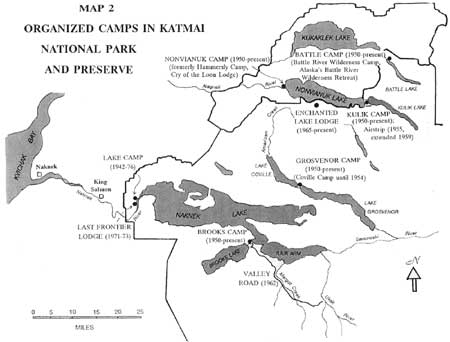

| Map 2. Organized Camps in Katmai National Park and Preserve (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

On February 15, Assistant Secretary of the Interior William Warne approved most of what Petersen had requested, and the NPS issued a draft concession permit, in the form of a Special Use Permit, for the two camps in the monument. Petersen was pleased to find that the permit was valid until December 31, 1954, three years longer than he had proposed. The permit allowed NCA the right to

carry on ... the business of camps and lodges with incidental facilities in connection therewith; and air and water transportation services on scheduled and nonscheduled bases, and to occupy land in said area....

The permit specified that NCA pay the government four percent of all revenue gained from camp operations and transportation to the monument, but excluding revenues from through air travelers visiting the monument on an incidental basis. [23]

The only changes requested by Washington NPS officials after the issuance of the draft permit related to reduced rates for accommodations while on official business within the monument. The permittee agreed to those changes, and on March 10, 1950, Concession Permit No. I-34np-299 was signed at the regional office in San Francisco. Ray Petersen signed on behalf of Northern Consolidated Airlines, and Alfred C. Kuehl signed on behalf of Grant H. Pearson of the National Park Service. Herbert Maier and E.M. Hilton, both regional officials, witnessed the signing. Regional Director O.A. Tomlinson approved the transaction. [24]

Many specifications contained within the permit differed little from those demanded of other lodge owners doing business in the national parks. The NPS, for instance, demanded approval of all specific camp locations, as well as of all buildings, structures or other improvements, and reserved the right to require removal of any inappropriate structures. They retained control over rates charged by the permittee and were able to remove any employees of the permittee "declared by the Regional Director to be unfit for such employment." [25]

Several other clauses in the permit were peculiar to the Katmai situation. One limited the number of overnight guests in each camp. Another required the permittee to "burn all garbage daily and dispose of all ashes and other refuse to the satisfaction of the Superintendent." To limit the daily catch, NCA was prohibited "from serving fish caught in the Monument except those caught by guests and others for their own consumption." [26]

Petersen promised other conservation measures not specified in the permit. His exclusive permit allowed him to set specific regulations on the number of fish taken. He also insisted that the Brooks River be limited to fly fishing. Petersen planned to use fuel oil, not wood, for cooking and heating, and vowed not to cut incidental timber without first obtaining a permit. [27]

Petersen encountered only token opposition to his plans. On April 20, 1950, Bernard Martin, an "interested party in the guiding profession" based in Anchorage, protested the issuance of the permit. He did so because of the exclusive nature of the permit and because granting such a permit was, in his opinion, an "extremely arbitrary and discriminatory action ... which is not in accord with usual government practice." [28] By way of reply, the NPS Chief of Public Services agreed that Department of the Interior regulations did not permit "similar camps in the same general areas assigned to the concessioner." He noted, however, that anyone holding an applicable permit would be allowed to perform guiding services in the monument, and was invited to apply for such a permit if he wanted one. [29]

Establishment and Construction of the

Camps

By the time Petersen had gained approval for his camps, little time remained for designing and constructing the camps before the summer season commenced. He gave the job of designing the camps to Vera Lieble, who was known at the time as western Alaska's "petticoat pilot." [30] Lieble was also a nurse who had supervised the building of various Bureau of Indian Affairs hospitals in interior Alaska. She ordered each of the camps to be constructed of a series of tent frames covered by olive drab-colored G.I. tents. [31]

The camps were constructed in the spring of 1950. While ice held firm on the mountain lakes, a wheel-equipped DC-3 landed supplies at most of the camp locations. By March 17, Coville Camp was under construction, and by May 3 it was ready for business. Nine days later, a converted Navy PBY flying boat landed on the open waters of Naknek Lake with the materials for Brooks Camp. Inasmuch as many of the construction materials had been precut prior to the flight, it required a relatively short period of time to prepare the camp. [32]

Those assigned to construct the camps included John Walatka, a pilot who was also conversant in bush construction techniques; John Pearson, who later built other lodges in southwest Alaska; and Bob Gurtler, a longtime Petersen acquaintance. They were assisted by several Eskimo craftsmen from the Kuskokwim area, including Nickenoff Evon and Raphael Kupanoak. Hired to supply kitchen facilities was Charles Blue, a Swiss chef who worked at the NCA camps for more than ten years. [33] Petersen had estimated in early 1950 that camp construction would cost between $4000 and $5000. When it came time to construct and equip the camps, however, Peterson urged the camp planners to supply whatever materials seemed reasonable and proper to the operation. As a result, the price tag for equipping the five camps ballooned to approximately $60,000. [34]

The NCA concession operation opened as scheduled. The first guest, a Texan named J.C. Hill, arrived in late May. [35] Shortly afterwards, from June 3 to June 5, Ray Petersen invited four Anchorage newsmen to Brooks Camp for a weekend of rainbow fishing. The scribes proudly proclaimed the opening of the new "sportsmen's heaven," where one guest found himself "tossing back 16-inch rainbow trout, because they were too small." Another declared that the trip was "worth it just for the scenery. I've used up several rolls of film and wish I had more." Petersen, for his part, remarked that "the Katmai region is one of the greatest attractions the North has to offer. We feel it is our economic duty to share it with the rest of the world." [36]

The completed camps were much as Petersen had envisioned them in January. Each was composed of a series of tent frames covered by olive drab-colored G.I. tent material. Brooks Camp, located on the flats just north of the mouth of the Brooks River, featured a 32' x 16' cookhouse and eight or nine guest tents, most of which were nine feet square. It had an advertised capacity of thirty guests. The other four camps accommodated between twelve and 24 guests. Battle Lake Camp comprised a 16-foot-square mess hall and kitchen, two other 16-foot-square sleeping quarters, and five nine-foot-square sleeping quarters. Kulik Camp was identical to Battle Lake Camp, except that it had four instead of five smaller tents. Coville Camp, located within the monument boundaries, featured a 16-foot-square cookhouse at the south end of camp, and one large and four smaller guest tents. Nonvianuk Camp, the smallest of the five camps, had just one 16-foot-square tent (the mess hall and kitchen) plus two nine-foot-square sleeping quarters. In addition to these improvements, Coville and Battle camps had pump houses, while Brooks, Coville, and Kulik camps had root cellars. [37]

Guests at the camps were rewarded with few amenities. Heat was supplied by oil-burning floor furnaces; guests slept in sleeping bags on cots. Brooks Camp offered running water, flush toilets, and shower baths, but the other camps had pit toilets. [38] The camps operated on the American plan (in which the fares included meals as well as lodging); they charged $25 per day that first summer. So-called transient guests were also able to stay and eat at the camps on a European plan basis, where food and lodging costs were itemized on an individual basis. [39] The first Brooks Camp manager was Doug Barnsley; the cooks were Vern and Vera St. Louis. The remaining camps were managed by husband-and-wife teams, some of which included children as well. The entire camp operation was managed by Hans Autur, a European-trained hotel man. [40]

The Korean Conflict, which erupted at the beginning of the summer season, depressed visitation levels throughout Alaska and moderated the expected tourist traffic to the NCA camps. Brooks Camp received 134 visitors, almost all fishermen, its first summer: one in May, 69 in June, 40 in July, and 24 in August. [41] Many of those visitors, however, were military personnel, guests of Mr. Petersen or NCA employees. Paying lodge guests, therefore, totaled 33 in June, eight in July, and an unknown number in August. The camp's capacity was never taxed; no more than ten anglers stayed at the camp at any given time. [42]

Tourists wishing to visit the NCA camps flew from Anchorage to King Salmon airport in one of the company's DC-3s, then headed down to the nearby Naknek River, where they transferred to either an eight-passenger, single-engine Norseman floatplane, an amphibious, war-surplus PBY, or a twin-engine Cessna T-50 on floats for the final leg of the trip. [43] The airline offered daily service. While many travelers made their own bookings, others took part in special three-day, all-expense-paid tours from Anchorage. Still others included a Katmai vacation as part of more extended NCA tours which lasted anywhere from ten to fourteen days. Short-term visitors probably limited their visits to the base camp at Brooks River. More long-term guests, however, were shuttled to the other four camps. [44]

Whether by accident or design, the National Park Service stationed its first seasonal ranger in the monument the same year NCA opened its concession operation. For years the agency had sought funds to create a presence; in June 1948, the Superintendent at Mount McKinley had gone so far as to name the person to be assigned and the anticipated starting date for patrol work. Personnel shortages, however, had prevented the patrol from taking place that year. [45]

The 1950 ranger assignment was implemented with a minimum of complication. On March 21, just eleven days after the concession permit was signed, Mount McKinley National Park Superintendent Grant Pearson noted that "after July 1, 1950 a Park Ranger will be stationed within the boundaries of Katmai," and by late April he chose William J. (Willie) Nancarrow as the Katmai ranger "as he has proven to be a very good all around man." He had hoped that the ranger would leave for Katmai in mid-June and return to Mount McKinley National Park on September 15. [46] Budget considerations, however, reduced that time to a two-month assignment that lasted from July 1 to August 30. A total of $2042 was authorized that summer for management and protection activities in the Katmai area. [47]

Following the dictates of staff at both Mount McKinley National Park and the regional office, Nancarrow took pains to establish his quarters and carry on his operations independently of the concessioner. [48] The ranger and concessioner, however, cooperated in several matters. Petersen, for instance, sold Nancarrow a surplus 9' x 9' tent which he used as a combined residence and headquarters. (This was located at the site of the present campground.) The concessioner was glad to have a ranger at Brooks Camp and occasionally offered him flights over the monument to assist in the patrol work. [49] Petersen recognized the prestige that monument designation added to his camps, and by the end of the summer he was moved to write that "the more I think of it the more I am inclined to agree that this area [Katmai National Monument] should be changed to a national park." [50] What was to become a long-term relationship between Ray Petersen and the NPS, therefore, began on a solid footing.

Land Acquisition and Patenting

Process

Brooks Camp and Coville Camp (later Grosvenor Camp) were on National Park Service land and were thus not available for purchase. As specified in various concession contracts issued over the years, the Secretary of the Interior allowed concession activities in "such pieces and parcels as may be, in his judgment, necessary and appropriate for the operations authorized hereunder." The location and acreage delegated for improvements, however, was not specified. NCA had a large degree of control and responsibility over its camps; as noted in various early concession contracts, the company had "a possessory interest in all concessioner's improvements consisting of all incidents of ownership, except legal title which shall be vested in the United States." [51]

Outside of Katmai National Monument, Northern Consolidated was free to apply for parcels from the Bureau of Land Management. As noted above, Petersen indicated an interest in two BLM parcels (Nonvianuk Lake and Battle Lake) as early as December 1949. By January 1950, he was interested in the Kulik Camp area as well as the other two sites and told an Interior Department official that

I am in hopes the Land Sales Bill of 1949, Regulations and Authority, will have been released at the time of our [February 1] meeting. The five-acre tract lease or purchase method does not, in my opinion, provide enough space to set up an adequate camp with room for expansion such as the building of lodges, tourist cabins and camp sites. [52]

In the spring of 1950, NCA constructed all five of the camps in which it had indicated an interest. It made no immediate move, however, to secure legal title to the land surrounding the three camps located outside of the monument. Following a long-standing custom, hundreds of Alaskans during this period had homes and businesses for which they had no legal claim; had the land been more valuable, airline officials may have tried to acquire it sooner. But as a BLM field examiner later wrote about the area, "the isolation, inaccessibility, and distance from populated areas of these lands are factors giving most persons no interest in acquiring them." [53] Four years later the airline began construction of an airstrip south of Kulik Camp; it likewise allowed this parcel to remain in public ownership for the time being.

On May 25, 1955, the airline applied to obtain four different parcels of land under the provisions of the Alaska Public Sale Act, which had been passed by the U.S. Congress on August 30, 1949. It began the process by requesting that the four parcels be classified for disposal in accordance with the act. Included was a 330' x 660' parcel (five acres) at Battle Lake, a 700' x 300' triangular parcel (five acres) at Nonvianuk Camp, a 990' x 495' parcel (11.25 acres) at Kulik Camp, and 80 acres at the Kulik Lake Airport. As part of the public sale process, NCA announced the intended use of the parcels; it proposed "to develop the first three parcels into camp and recreational sites, suitable for the most discriminating fishermen and hunters." The fourth was intended for use as an airstrip. [54]

By April 1956 the Bureau of Land Management had classified and surveyed the four parcels. It reduced the size of the requested plots to 3.98 acres at Battle Lake, 2.36 acres at Nonvianuk Camp, and 10.64 acres at Kulik Camp. The size of the airstrip claim was not reduced. [55] The following month it announced that, under Classification No. 22 of the Public Sale Act, it was holding a public auction for the four parcels. The minimum bid prices for the parcels, as listed above, were $350, $325, $300 and $650, respectively. Because the land surrounding the tracts was neither timbered nor of agricultural use, the bid prices were quite nominal. The land itself was valued at $2.50 per acre, to which the cost of the survey was added. [56]

On June 4, 1956, Alaska Public Sale No. 22 was held. NCA offered the minimum bid on all four tracts; its bid was accepted in each case. [57] Once the application process was underway, the BLM required a proposed program of use and development for the lands as well as proof of the financial means to carry out those plans. It also required that the lands be used for the same purpose for which they had originally been classified. [58] The airline had no particular difficulty in satisfying the various land acquisition requirements, and the patenting process was allowed to smoothly proceed. In April 1957 the airline was issued a Certificate of Conditional Purchase for each property. The office was provided an Application for Patent/Proof of Use in August 1958, and on October 26, 1960, NCA was awarded patents for each of the parcels for which it had applied some four years earlier. [59]

It took ten years, therefore, for NCA to gain full ownership over the three camps located outside of the monument boundaries. Combined with the concessions agreement it arranged with the National Park Service, the airline was thus recognized as the primary way for fishermen to gain access to the increasingly well-known fishing opportunities of the Katmai country. NCA never showed interest in opening up more camps than the five it established in 1950; the park service, in turn, never seriously entertained proposals to establish camps from rival companies. NCA and the NPS thus benefited from a mutually advantageous relationship. The camps helped publicize an otherwise little-known regional airline, and in so doing provided access to the monument for the general public as well as to camp guests. They thus provided a sufficient degree of development and access to legitimize the right of the agency to continue its jurisdiction over the monument. The park service, in turn, provided a degree of exclusivity to the camps. Their location on NPS land also lent a certain degree of prestige; although many Alaskans felt that the park service was a hindrance to development, Outside visitors generally favored its presence. NCA and its successors have continued that relationship to the present day.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

katm/tourism/chap2.htm

Last Updated: 13-Oct-2004