|

Katmai

Tourism in Katmai Country |

|

CHAPTER 3:

NORTHERN CONSOLIDATED CONCESSION OPERATIONS

Between 1950 and 1968, Northern Consolidated Airlines was the monument's only concessioner. During the 1950s the camps appealed primarily to fishermen, and provided basic levels of comfort. The airline proposed several improvements in the monument; some were fairly whimsical, while others, such as an airport near Brooks Camp, were rebuffed by agency personnel. In 1960 it undertook a major building program at Brooks Camp, and shortly afterward it pressured the NPS into constructing a road to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Once completed, the improvements began to lure a growing number of non-fishing tourists, and the number of independent travelers became increasingly significant.

Concession Activities During the

1950s

The first decade of Northern Consolidated Airlines camp operations was characterized by good relations between the National Park Service and the concessioner, rustic camp facilities, and a relatively limited array of activities offered to camp guests.

The camps that had been constructed in the spring of 1950 were improved little during the remainder of the decade. The only real improvement took place in the mid-1950s, when many of the original tents were replaced by plywood boards, then overlaid by asphalt shingling. Guests continued to sleep in sleeping bags on cots, and were not bothered by such amenities as telephones, television, or motor vehicles. Communications with the outside world were by airplane or radio. [1] These camps, which were collectively known as "Angler's Paradise," had been constructed primarily for fishermen. In 1952, an NCA official noted that "99% of the present clientele were fishermen," and as late as 1957, a guide noted that "almost everyone who visits the Monument is there to catch salmon and trout."

In order to publicize the camps, Petersen invited a host of outdoor writers to the camps. [2] The New York Times, the Christian Science Monitor, and the Seattle Times responded with extensive, glowing reportage, and a score of other newspapers also provided publicity. The major outdoor magazines, such as Field and Stream, Outdoor Life, and Argosy, also sent writers to Katmai. The major Alaska publications, including Alaska Sportsman and the Anchorage newspapers, supported the camps. In addition, several filmmakers came to the camps and featured Katmai footage on Alaska travel documentaries. [3] Both writers and filmmakers wrote glowing reports of the Katmai's fishing possibilities. They extolled the huge size of the fish and the ease of catching them; they also noted the wide variety of species available: rainbow, steelhead, Dolly Varden and lake trout, along with grayling, sockeye salmon, and northern pike. [4]

To personalize the NCA publicity campaign, the company hired a local homesteader, Rufus Knox "Bill" Hammersly, to promote the camps. Hammersly had lived in Alaska since 1926, and had worked as trapper, prospector and hunting guide; by 1945 he had established a homestead at the outlet to Nonvianuk Lake. Five years later, NCA established a camp adjacent to his claim, and hired him as camp manager. Tall and rough-hewn, and sporting a full, graying beard, Hammersly personified the image of an Alaskan miner, and his life in the bush authenticated that image. During the winter of 1950-51, therefore, Hammersly toured the United States and told salty tales about life and fishing to a wide range of radio and television audiences. [5]

The publicity gained from the initial advertising campaign was successful in attracting a solid clientele. Customers evidently liked what they saw and told their friends, and before long, a regular customer base had been established. The continuing popularity of the camp experience obviated the need for additional articles or advertisements, and after 1953 only scattered articles on Katmai appeared in the various travel and outdoors magazines. [6]

When plans for the camps were first laid out, NCA officials espoused a variety of proposed activities at the camps. An article which accompanied the opening of Brooks Camp in 1950 noted that

present plans call for a 22-foot cabin cruiser for deep-sea fishing on Naknek Lake in search of mysterious giant fish described by natives, and establishment of another camp in the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. [7]

Shortly thereafter came the announcement that

the airline will co-operate with the National Park Service this summer in prospecting and laying out horseback trips. It is planned to provide these next summer, with overnight rides into the "10,000-Smokes" area and other spots of fascinating geologic interest. [8]

By the end of the summer, a travel writer noted that

the airline plans to establish tourist camps throughout this region, including possibly a Sun Valley of the northland near the famed Katmai Valley. [9]

Despite the optimistic statements, almost nothing more was heard from any of these plans. Good fishing and the scenery that accompanied it were the main attractions, along with the delicious, plentiful food offered as part of the stay. [10] Although advertisements were quick to note the nearby Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, the valley was available only to those who chartered planes. Due to the uncertainties of weather, however, many were unable to make the trip. [11]

Even though the concessioner advertised hiking as a camp attraction, the only trail available to lodge guests was one from Brooks Camp to the north side of Brooks Falls; this trail followed the same ridge used by the present Eskimo Pit House trail. In 1951, NPS ranger Morton Woods cut a trail from Brooks Camp to Brooks Lake; it was probably an extension of the existing Brooks Falls trail. [12] Fishermen who headed directly to the falls did not need to cross the river, but many of those who fished the banks along the lower stretches of the Brooks River, and the staff at the Brooks Lake fisheries station, had to use boats for the crossing. Several plans during the 1950s proposed the construction of a footbridge; in 1956 work was done on a bridge, but it was damaged the same year by high water. Nothing more came of the plans. [13] The only other form of travel around the monument was by boat. Fishermen rented skiffs with or without motors, and every few years the concessioner also had a large boat that was used for travel around Naknek Lake. [14]

When the Alaska Recreation Survey investigated the possibilities of the Katmai area in the early 1950s, they envisioned that many new activities could be developed over time, some by the concessioner. George Collins, chief of the Survey, agreed with Ray Petersen that "a diversified program for visitors" was needed. Elements of the proposed program consisted of a trail to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, which would eventually be followed by a one-way road with turn-outs, which went as far as the divide overlooking the valley. In time, Collins felt that "helicopters might answer the problem of getting visitors within short walking distance of Novarupta Volcano...which they should have the experience of actually touching if they can." He advocated Petersen's use of aircraft for flights over the volcanic area and hoped to see flights continue on to landing fields at Geographic Harbor and Kukak Bay. He envisioned the creation of tours of the clam cannery then operating in Kukak Bay and urged the eventual creation of a concessioner-operated boat trip on the principal lakes and rivers of the area. [15]

In retrospect, some of the ideas advocated by the Survey appear fanciful, just as NCA's ideas had been during its first year of operation. That more ideas have not been realized cannot be considered the fault of either the Service or the concessioner. Instead, factors that insured the continuation of the status quo were the tightfisted budgets of both parties, the relatively small number of guests to the vast preserve, and the escalating value that the public held toward the nation's wilderness resources.

In order to entice visitors to the various fishing camps, Northern Consolidated offered several different tour packages during the 1950s. These were sold by various U.S.-based airlines. [16] In 1951 and 1952, fishermen could choose between three-day and seven-day packages. A year later a one-day option was also available, but by 1956 the one-day trip had been dropped and a two-week tour added. Patrons on most trips did not sign up for a particular camp; instead, the airline offered to "take you to where the fishing is the 'hottest' at the moment." [17] For this reason, most fishermen did not sign up to fish at a particular camp; instead, most came to Brooks Camp first and were then flown out to one of three other camps. [18] (Battle Camp, found to be a relatively poor location for fishing, was rarely mentioned in company promotional efforts.) John Walatka was the chief pilot to shuttle fishermen to and from the various camps; [19] others were "Swede" Blanchard, an Anchorage-based guide and veteran bush pilot, and R.J. Stevenson, a longtime NCA pilot. [20]

Camp photographs from the 1950s, and the reminiscences of Katmai visitors, confirm that the camps contained many aspects of a wealthy, rustic men's club or fraternity. There were no restrictions, of course, as to who could visit, and independent travelers, who stayed at the nearby campground, were freely able to mingle with the lodge guests. But the cost of a Katmai trip, particularly for those who lived outside Alaska, was so prohibitive that only a select few were able to visit the camps. Many of the guests, therefore, were business leaders; both Alaskan and U.S. points of origin were well represented. A small though visible number of political leaders and Interior Department officials also paid a visit during the early years of the camps; because of the camp's superb fishing, the trip became a critical part of their Alaska tour. [21]

Each of the five camps, as noted in the ad, had a different optimum fishing period. Therefore, anglers arriving early in the season found the best prospects at Brooks Camp, for example, while those arriving progressively later in the season fished at Coville, Nonvianuk, Kulik and Battle camps, respectively. [22] The changing fishing peaks resulted in some camps being open much less than a full season. Coville Camp typically operated for four to six weeks during June and July, and the camp at Battle Lake did not usually open until August. [23] Brooks Camp was originally open only during June, July and August, in order to coincide with what was purported to be the best fishing season. In 1952, however, the camp was "kept open well into September ... because fishing had turned very good just at the time the camp was scheduled to close late in August." Thereafter, the camp continued to stay open through the first or second week of September. [24]

One of the main reasons that airline management established the camps was to stimulate travel on its aircraft, and to be associated with the prestige of a well-known resort. [25] Considering the length of the season and the financial outlay required to establish the camp facilities, the camps were not expected to be profitable, at least over the short term. Those humble expectations were largely fulfilled for their first years of operation. An analyst of the first summer's operation noted that because of the "situation in Korea ... the success of the two camps installed within the monument was not financially satisfying." Scattered financial reports showed that the five Katmai area camps had negative net income figures for the next seven years. [26]

Relations between the concessioner and the National Park Service remained generally cordial during the first several years of camp operation. In the 1950s the two operated on a complementary relationship; the Service valued the concessioner because it brought visitors into the region and thus opened up the park to outsiders, and the concessioner valued the existence of the national monument because the designation helped underscore the value of the fishing resource and thus attracted visitors to the camps. During this period the concessioner and the National Park Service were generally happy with the existing level of development.

As the decade wore on, however, relationships between the two parties occasionally became strained. Part of this feeling developed because the concessioner began to assume a proprietary feeling for the camps. It had, after all, built five camps in or near the monument, provided for access, housed a large majority of Katmai visitors, and employed personnel at each camp. The NPS, on the other hand, was hard-pressed to support a single seasonal ranger. The concessioner, therefore, felt justifiably angry when it proposed developments that the Service could not support.

One factor complicating the relations between the concessioner and the NPS was the nature of the decision making structure in the two organizations. The concessioner was effectively represented by just two men, President Ray Petersen and Camp Manager (or Camp Superintendent) John Walatka, who also served as chief pilot. Others in the organization who dealt with the NPS included managers and cooks at the individual camps and financial officers in Anchorage. [27] Petersen and Walatka, however, made most decisions for the concessioner regarding camp operations. They formed an effective working team for some twenty years. Petersen's voice appears to have been the stronger of the two, for regardless of his other responsibilities he took a strong, personal interest in the welfare and operations of the Katmai camps. [28]

The decision making structure of the National Park Service, as it pertained to the early Katmai camps, was far more diffused. It consisted of a seasonal ranger at Brooks Camp, a superintendent at Mount McKinley, officials in the Region Four (later Western Region) headquarters in San Francisco, and national officials in Washington, D.C., all of whom created regulations, interpreted policy, or worked on the creation of new contracts. These personnel, moreover, were rotated or otherwise replaced every few years. As long as the camps remained at the status quo and regulations remained relatively simple, relations remained good. But attempts at camp development, the growing complexity of Federal regulations, and the multilayered, sometimes contradictory levels of NPS management often combined to anger and frustrate both concessioner and bureaucrat. These forces surfaced soon after camp operations began.

Erection of Permanent Buildings,

1956-1964

For the first three years of camp operations, both guests and management were satisfied with existing facilities. Most fishermen liked the "certain quality of primitive charm and Bohemian atmosphere to tent cabins furnished with double decker bunks and sleeping bags," and resisted attempts to change it. [29] But in October 1952, the airline announced that it also hoped to attract the sightseeing tourist—the kind of visitor "who goes places just to be amazed," as one travel promoter put it. This type of visitor expected more than tents and oil heat; therefore, the airline made plans to fly a prefabricated lodge up from Seattle. Brooks Camp, "on a site overlooking Brooks Falls," was considered, but NCA officials were also willing to investigate a site at the mouth of Margot Creek, which was located near the site of Savonoski, a former Eskimo village. They were apparently responding to recommendations of the Alaska Recreation Survey, which had recently reported that the monument's "main tourist center" should be located at Margot Creek, a salmon-bearing stream with easy access for a potential road into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. [30] But by the following January, the Margot Creek site had been dropped from consideration, and the airline announced its intention to build, from local materials, a 30' x 60' log cabin along the Brooks River "to be used as a central hall for eating and recreational facilities." Superintendent Pearson flew out to investigate. [31]

In the spring of 1954, Petersen approached regional NPS officials with more sophisticated plans. Recognizing that he was in the last year of his five-year concession permit, he offered to construct a permanent lodge at Brooks River and additionally proposed to replace the existing tent frames with cabins, all in return for a seven-year contract. The Service liked the proposal.

After the contract had been prepared, however, Petersen complicated matters by conditioning the acceptance of his building plans on the construction of an airstrip in the vicinity. (He felt an airstrip was needed because winds made it difficult, and sometimes impossible, to land float planes on Naknek Lake.) The Service, for its part, muddied the waters when it told the concessioner that it would not finance the construction of a utility system at the camp. Petersen had apparently hoped or expected the NPS to underwrite such costs, but in a July 1954 memorandum an NPS official stated that "it is not feasible for the Service to provide such facilities for the concessioner, unless and until we have a development in the immediate vicinity requiring utilities." [32]

Regarding the airstrip idea, NPS Director Conrad Wirth responded in a February 9, 1955, teletype, noting that "if airstrip is to be built in Katmai, I am not sure Brooks Lake is proper location. Further study needed before answer can be given." [33] The Director, in fact, questioned the advisability of developing Brooks Camp into a major concession area; he felt that the Savonoski area, at the east end of Iliuk Arm, should be studied as an alternative concession area. [34]

The controversy temporarily held up the ability to renew the concession permit on time—a practice which was to be followed many times in the coming years—and the concessioner operated through the summer of 1955 without a valid permit. In June of that year, Park Landscape Architect Charles E. Krueger visited Brooks Camp to study the airstrip situation and identified two sites south of the Brooks River that would be acceptable for an airstrip. [35] But the concessioner refused to promise a building program, and a new three-year contract for the 1955 through 1957 seasons (Contract No. 14-10-434-80) was signed by the concessioner and Superintendent Grant Pearson on February 20, 1956. The agreed-upon franchise fee was changed from an unwieldy four percent of camp and air-travel revenues to a flat $250 fee. [36]

Though the prospects for an airstrip near Brooks Camp appeared bright, NCA moved quickly to establish another airfield in the vicinity. The company recognized that areas outside the monument demanded less stringent bureaucratic regulations; in the summer of 1954, therefore, employees began to blade off a 1500-foot runway on Bureau of Land Management land just south of Kulik Lodge. The following year, NCA moved to have the airstrip extended to 2000 feet and presumably finished work by summer's end. By August 1956, workers had completed "a usable road satisfactory for the operation of a Willys Jeep" between the landing strip and Kulik Camp. To legalize its improvements, company officials in May 1955 applied to patent an 80-acre parcel which included and surrounded the airfield. NCA obtained a patent for the parcel on November 2, 1960. [37]

The first permanent wood frame buildings at the concessions camps were erected at Brooks Camp in 1956. NCA constructed a prefabricated, simulated log "Panabode" style building; its dimensions were 20' x 24'. Completed on August 3, it served as a combination store, office, and manager's quarters. That same summer the National Park Service built the Brooks Camp ranger station and the nearby generator shed. [38] The following year, NCA constructed a structure similar to its Brooks Camp facility at Coville Camp, which had recently been renamed Grosvenor Camp. The Panabode-style structure has served as a manager's office, residence, and lounge ever since. [39]

Visitation to the NCA camps increased sharply during the next several years. In 1950, as noted above, only 134 visitors had come to Brooks Camp. But by 1956, the number had jumped to 510, and by 1959 it had more than doubled to 1083. [40] While statehood-oriented promotions and general tourism growth helped spur visitation to the camps, at least some of their increased popularity during the late 1950s and early 1960s was due to successful tour marketing. Beginning in 1958, Northwest Airlines teamed up with NCA to promote three-day "Fishermen's Special" tours from Minneapolis-St. Paul (later Chicago) to the camps. Weekend trips were particularly popular. [41] Even so, about ten percent of Brooks Camp visitors did not fish. [42]

NCA responded to the increased visitation by adding new tents at its Brooks Camp facility. The camp grew from an estimated eight or nine tents in 1950 to a 22-tent complex in 1959; the latter complex included the Panabode store, office and manager's quarters, a kitchen and dining room, a bathhouse, a power house, a storage shed, and numerous dormitories and cottages. Development also took place at Grosvenor Camp; new construction consisted of a bathhouse and two cabins, all made of Panabode-styled cedar. By early 1960, the camp had grown into a complex that included four log buildings, six tent-covered structures, and a power house. [43]

Recognizing that future growth was dependent upon an improvement in facilities, Ray Petersen approached the agency in late 1959 with development plans for his camps. He met with regional officials in mid-November. During that meeting, he offered to undertake a camp construction program, but only if he could secure a long-term contract. (The existing contract, a three-year pact signed in March 1958 for the 1958 through 1960 seasons, was virtually identical to the one signed in February 1956.) [44] On January 2, 1960, he and John Walatka activated Alaska Consolidated Vacations, Inc. (ACV), a wholly-owned subsidiary of Northern Consolidated Airlines, and transferred the real and personal property of the five camps, which held a book value of $65,000, to the new corporation. [45] The corporation was created to segregate camp affairs from those of NCA and to serve as a vehicle for camp development. It had the aggressive goal of increasing the capacity of the camps from 100 to 142 guests by the opening of the 1960 season "through the purchasing and erecting of additional log-type facilities at Kulik, Nonvianuk and Brooks Camps." [46] The camps were operated by the new subsidiary until January 1, 1963, when control of the camps was once again assumed by Northern Consolidated Airlines, Inc. [47]

In February 1960, Petersen told Samuel King, the superintendent at Mount McKinley National Park, that in return for a twenty-year concession, he intended to "plan and finance substantial improvements of facilities in the Monument in order to accommodate the rapidly expanding tourist demand." [48] Petersen went on to promise that the materials for the Brooks Camp facility would be landed on the ice early that spring. [49] King, meanwhile, approved the idea of a twenty-year concession in a letter to Regional Director Lawrence Merriam. But a meeting to discuss details of the proposed contract was postponed because revisions in the standard language for NPS concessions throughout the country were being proposed. [50]

Despite the slowdown in contract negotiations, development plans continued. During April 1960, the Park approved drawings to construct a mess hall at Brooks Camp. [51] The mess hall, which is the older portion of Brooks Lodge, was constructed that year. The building was described as a "red cedar Pan-A-Bode Lodge 50' x 24' with a 20' x 20' kitchen added on." In addition, seven Brooks Camp guest cabins, noted as "12' x 14' Pan-A-Bode red cedar cabins," were erected. They completed the outside of the buildings that year, as well as installing "a large approved cess pool" and a new Witte Diesel power plant. Such items as a new pressure water system as well as the wiring, plumbing and furnishing of the buildings were not finished until early 1961. [52]

Having thus stuck out its financial neck, the concessioner became more militant with the NPS regarding the creation of a long-term contract and also demanded that the agency provide its own funds for Brooks Camp improvements. In December 1960, Walatka remarked that ACV was negotiating $150,000 in financing, "most of which will be used in Katmai and for working capital, in order to finish our program." To make the loan worthwhile, however, he implored that the Service allow "a ten or preferably a twenty year concession." He also hoped that the service would "do something concrete...such as docks, roads, trails, an airport, water, sewer and power and a museum as is done for other concessioners in the Park system." [53]

Although the regional director was cool to the idea of spending development dollars in a park that had received only about a thousand visitors per year (one of the lowest totals in the system), he was glad to send along his approval of a ten-year contract to Washington. [54] But when Petersen visited Assistant Director Jackson Price there in February 1961, he was told that all new concession contracts were now receiving qualified legal clearance, and all long-term contracts were thus being held up. Price urged Petersen to accept a five-year contract, which could be prepared and executed promptly, and further told him that "he could apply for a new long-term contract on the basis of the completion of his construction program." [55] On April 2, Petersen and Walatka met with Mount McKinley Superintendent Samuel King; they told him that the contract was acceptable to them for the five-year period specified. They did, however, point out that a contract of longer duration "would be preferable to the company." The concessioner further agreed to raising the annual franchise fee, from $250 to $900.

On April 25, 1961, Petersen and Walatka met with Elroy Bohlin, the acting superintendent, and signed Contract Number 14-10-0434-498, which certified that Alaska Consolidated Vacations would be the Katmai concessioner until December 1965. This contract and the original 1950 permit were the longest-running Katmai concessions pacts that had yet been signed. The parties had no way of knowing it, of course, but the 1961 contract, as amended, was to remain in force throughout the 1960s, all through the 1970s, and on into the following decade before it was finally replaced in the fall of 1981. [56]

With a concession contract in hand, the concessioner continued its improvements at Brooks Camp over the next several years. It completed and furnished the lodge and the seven small Panabode guest cabins in 1961; the combination comfort station/bathhouse, located between the lodge and cabins, was finished the same year. But it still had 15 tent frames in use that summer. [57] In 1964, NCA added the Skytel, a nine-unit guest building. [58] It then began to phase out use of the old tent cabins to guests, and by 1965 only seven remained, all of which were used for employee housing. [59] Therefore, guest capacity in late 1964 was 36, only slightly higher than had been the case in 1950. [60]

Modernization also took place at two of the three camps located outside the monument. Kulik Camp, the largest camp next to Brooks, saw the largest amount of new construction. In the summer of 1956, the camp consisted of three 16 x 16 tent cabins, four 9 x 9 tent cabins and a root cellar. Over the next several years, however, NCA pushed camp development in order to coincide with airport and scheduling improvements. By early 1960, therefore, the camp had exploded into a 26-building complex, including eight log buildings and at least 13 tent frames. [61]

Key to development of Kulik Camp was a sawmill and planing mill. Installed in the summer of 1956, the mill first provided materials for the camp's 30' x 50' lodge building. The lodge was still under construction in 1958, but was completed by early 1960. Also completed by that time was a bath house, five cabins and a shop and power house, all made with logs cut on site. By the following year it had furnished logs for the camp's main office. The sawmill continued to operate until the early 1970s; its last project was the north wing of the shop and power house. [62]

The Kulik sawmill also cut the wood used in the main lodge building at Nonvianuk Camp. In early July 1960 construction began on the 60' x 16' building; materials were floated down Nonvianuk Lake. [63] The structure was controversial while still in the construction phase. Robert Hammersly, son of homesteader Rufus K. "Bill" Hammersly, was convinced that the building was impinging upon his family's property claim. Therefore, he lodged a protest to that effect to Bureau of Land Management officials. [64] The cabin was the largest of several new buildings added to the complex during that period. In August 1956, the camp consisted of just three tent cabins, a mess hall and kitchen cabin, and two sleeping cottages. By late 1960, however, the camp boasted a radio house, a power house, and two new sleeping cottages, as well as the main lodge building. [65]

A significant, if brief, spurt of activity also took place at the Kulik Lake Airstrip. During its first few years of existence, use of the 2000-foot facility was limited to small bush planes. In October 1958, however, NCA acquired the first of several Fairchild F-27B propjets, 40-passenger planes which offered a higher standard of speed and comfort than anything previously available. [66] In conjunction with the purchase, the airline chose Kulik Lake Airfield to fulfill the role of intermediate stop on the Anchorage-King Salmon run. It did so with the prospect that Kulik Lake might emerge as another major facility like that at Brooks Camp.

To accommodate the proposed traffic, the airline lengthened the runway 2000 feet to the east in 1958. The new construction extended well beyond the boundary of the 80-acre parcel which the NCA had applied for in 1955. In 1959, Federal Aviation Agency records reaffirmed the existence of the 4000-foot strip, with 600 additional feet of overrun and soft sand. The airstrip was approved for use by both DC-3s and F-27s. [67]

In early 1959, NCA began F-27 service to Kulik Lake. Over the next three years the airline continued to offer direct seasonal service from Anchorage. The airstrip was sometimes used as a regularly scheduled weekly stop, but at other times as a flag stop. [68] By 1963, however, NCA officials were forced to concede that service to Kulik Lake with such a large, noisy plane was not a paying proposition. Furthermore, guests at the nearby lodge let it be known that they preferred a small facility. Direct flights from Anchorage to Kulik Lake were therefore discontinued. [69]

Although FAA records show that the original airfield was extended some 2000 feet onto public land in 1958 or 1959, NCA took no action for the legal use of that land until 1962. On January 10, 1962, the airline applied to the Bureau of Land Management for a twenty-year Public Airport Lease, which included two parcels surrounding the existing airfield. One parcel, 2500 feet long and 1320 feet wide (75 acres in extent), encompassed the late-1950s extension of the runway; the other was a 400-acre parcel, southwest of the runway, which was unrelated to airport operations. During the BLM's investigation of the lease application, the FAA informed the BLM that the location of the 400-acre parcel was inappropriate for a Public Airport Lease. The BLM, therefore, tentatively approved one part of the lease application while rejecting the other. [70]

NCA officials did not appeal that decision and were on the verge of signing the lease in June 1964. The necessary paperwork, however, was lost or mislaid by persons unknown, and the matter lay at a standstill until 1968, when the BLM again brought the matter to the airline's attention. NCA decided to accept the lease, and sent in the first year's rental payments. Before the lease was allowed to take effect, however, a Native protest suspended further action. On April 12, 1967, the Kodiak Area Native Association, the Bristol Bay Native Association, and the Alaska Peninsula Native Association had filed a protest over these and many other lands in southwestern Alaska. That action, for the time being, put leases and other conveyances on hold. [71]

Although half of the lengthened airstrip was on unleased public land, NCA ran it as a private facility. In 1960, for example, pilots visiting the airstrip were confronted with the following sign:

KULIK AIRPORT

PROPERTY OF

NORTHERN CONSOLIDATED AIRLINES

INC.

LANDING PROHIBITED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION

FROM NCA OPERATION MGR. AT ANCHORAGE

LANDING FEE $25ºº PER PLANE OR $10ºº PER OCCUPANT

— WHICHEVER IS GREATER —

PARKING FEE $5ºº PER PASSENGER PER DAY

AFTER FIRST 24 HOURS

Arguing that the strip was "not certified for public use by the state of Alaska or the FAA," the airline declared that except for emergency purposes, "under no circumstances does the company permit the use of this private strip"; furthermore, it had "no intention of making this strip available for public use." The owners demanded written permission from all those who wished to land, and threatened legal action against those who did not obtain such permission. [72]

Development of Concession Activities,

1960-1968

When Petersen met with National Park Service officials in late 1959 and early 1960 about his proposed construction program, he hoped to develop the Katmai camps by appealing to the non-fishing visitor. Until that time, fishing was the predominant activity. The only improvements built in the monument in the 1950s (aside from the camps themselves) had been two trails: one following the north side of the river from Brooks Camp to Brooks Lake via Brooks Falls, the other a 1.5-mile trail, constructed by 1959, from Brooks Camp to the Dumpling Mountain overlook. Both had been cut by NPS rangers, and by 1960 were "already overgrown with brush and grass." [73]

Petersen felt that the greatest unmet need in the monument was access to the Valley of the Ten Thousand Smokes. Poor weather and the expense of chartering a plane often prevented camp visitors from flying over the valley, and Petersen was certain that a road connecting the valley from Brooks Camp was the most viable solution. He had advocated the construction of a road "from some point on Naknek Lake" to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes as early as September 1950. The following year the NPS gave lukewarm support to the development of a trail to the valley, but the only effort to secure a road during the 1950s was the Alaska Recreation Survey proposal noted earlier. [74]

By 1960, the agency was well under way with its MISSION 66 program, which intended to upgrade the condition of park facilities across the country. At Katmai a $1.2 million, broad-based program was proposed which intended to disperse the activity pattern at the monument. It included an airstrip, several campgrounds and docks, a visitor center, 25 miles of trails, employee quarters, and other administrative facilities. [75] The plan also envisioned a road along much the same lines as that proposed by the Alaska Recreation Survey; that is, a ten-mile road that would "provide access from Naknek Lake to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes via the Ukak River Valley." The visitor center was intended to be at the base of that road. (The plan called for either planes or boats to connect Brooks Camp with the mouth of the Ukak River.) The road, however, was not a top priority; NPS employee quarters, a visitor center, and an airstrip were all considered to be more important. [76]

When Petersen met with the NPS in early 1960 to lay out his development plans, Director Conrad Wirth and other officials promised verbal support for a road if Petersen would enhance the facilities at Brooks Camp. [77] Petersen, true to his word, fulfilled his part of the agreement during the summer of 1960. But when Petersen returned to Washington the following February, Assistant Director Jackson Price noted that the best he could hope for would be "a pioneer road of about twelve miles in length around the base of Mt. Katolinat which could be reached by boat from Brooks River," the terminus of which would be the base for four-wheel vehicle trips into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. [78] And according to George Sundborg, an administrative aide to U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening, even a twelve-mile road was not possible because of opposition from the Sierra Club or other preservationists. [79]

After Sundborg informed Petersen of the status of the project, Gruening arranged for a meeting the following day with both Petersen and Director Wirth. At that meeting, Gruening convinced Wirth to commence road construction despite objections; as Petersen remembers the conversation, "the old Senator grabbed this guy [Wirth] by the scruff, and says 'you don't treat a constituent like this.'" [80] Six months later, Katmai Ranger-in-Chief Robert Peterson led a party which surveyed the route, and a Project Construction Program Proposal for the $205,000 road building job was drawn up shortly afterward. Construction, financed by the NPS, began in early 1962 and was completed by the end of the season. [81] The first tours up the road, using either a 16-passenger bus (a converted, surplus military ammunition carrier built on a cab-over 1961 GMC frame) or an 8-passenger Chevrolet carryall, began in 1963. [82]

The Congressional pressure which led to road construction threw the MISSION 66 program for the monument into disarray. The $200,000 spent on the road relegated all other park functions to a lower priority, and budget realities combined with low visitor figures demanded that developments were significantly less than had been planned. Road construction had the practical effect of centralizing more of the park's resources on concessioner-oriented activities; it also ensured that future activities revolved around Brooks Camp, rather than the more dispersed program called for in the MISSION 66 prospectus.

The road spawned several ancillary developments. Spur trails to Margot Falls and the summit of Overlook Mountain were completed in 1962. [83] By the time the road was complete, the NPS had built a 24' x 28' reception center at Windy Creek Overlook, and by early 1963 had created the one and one-half-mile trail that connected the overlook with the Ukak River. [84] In the Brooks Camp area, 1962 witnessed the extension of the Dumpling Mountain trail from the overlook to the summit; the same year, the Brooks Falls trail was relocated from the north to the south side of Brooks River. Materials for three Panabode cabins and the boathouse were flown that spring, and the following spring a DC-3 brought in the materials needed to construct a warehouse. The cabins were used by construction personnel during the road project. [85]

The road also brought a significant increase in the number of visitors who needed to cross Brooks River. To make the Brooks River crossing more convenient, small docks were constructed on both banks. On the south bank a small, L-shaped dock was built near the present bus loading area, while on the north side a linear dock was laid out at the head of a small embayment. This embayment, which no longer exists, was located just upriver from the mouth of the Brooks River and downstream from the road terminus. The concessioner used several small powerboats to carry the guests back and forth across the river. [86]

The new road, as expected, attracted general tourists as well as fishermen to Brooks Camp, and the airline increasingly began to tailor its tour packages to cater to the new market. The seven-day and two-week vacations that had attracted fishermen in the 1950s were dropped, and three-day vacations were promoted almost exclusively. Some of the three-day packages, of course, were purchased by fishermen, but by 1965 an observer remarked that "already enough tourists get to Brooks that the diehard fishermen are going to Grosvenor." By 1967, it had become apparent that a broad range of visitors were coming to Brooks Camp. [87] The new class of tourists fished less than those that came before, and many did not fish at all. More important to them was the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes Tour combined with scenery and wildlife observation in the Brooks Camp area. [88]

The establishment of Brooks Lodge as a general tourist facility, and success of the bus tour, also brought the first significant number of independent travelers to the monument. These visitors flew into Katmai in the same manner as guests at the NCA facilities, but independent travelers stayed elsewhere, usually at the Brooks Camp NPS campground. Available figures, which appear to be reliable, indicate that before the road was opened, the seasonal total of overnight stays at the Brooks River campground seldom exceeded one hundred. This averaged out to less than one camper per night during the summer season. Visitation grew during the next several years, however, and by 1967 some five hundred overnight campground stays were recorded. [89]

|

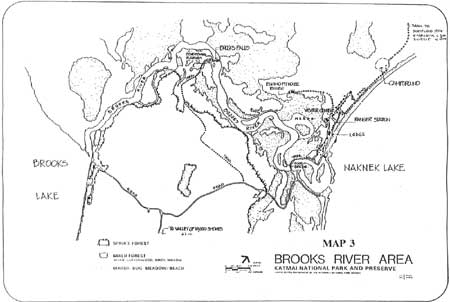

| Map 3. Brooks River Area (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The swelling number of campers and the other independent visitors at Brooks Camp became a source of resentment for the concessioner, because they used NCA's facilities without paying for their use. These visitors, for instance, often loitered in and around the main lodge, and on rainy days some of the bolder campers used concession buildings for drying their clothing and equipment. [90] A deeper reason for resentment of the independent traveler was that Brooks Camp area was no longer dominated by the concessioner. In the 1950s few but NCA visitors ventured to Brooks Camp; perhaps as a result, several NPS observers felt that visitors were largely unaware that the camp was located in a national monument. They also sensed that the concessioner had acquired a proprietary, clubby feeling toward the camps. Part of this attitude, which lasted as late as the early 1970s, was that the proper role of the National Park Service was to serve the concessioner. [91]

While the prevailing attitude caused the NPS personnel to experience hard feelings toward the concessioner, NCA felt equally angry at the NPS because it would not fund general improvements. Shortly after it undertook its building program, John Walatka wrote the agency and wondered aloud why it could not do "something concrete for the Concessionaire such as docks, roads, trails, an airport, water, sewer and power and a museum as is done for other concessionaires in the Park system." [92] Many of these improvements were eventually provided, but as late as 1965 an obviously exasperated Ray Petersen complained to Ralph Rivers, Alaska's Congressman at the time, of the Service's "shabby" treatment of NCA, noting that the only significant improvement at the monument had taken place only after Senator Gruening had prevailed upon NPS Director Wirth to build the road to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. [93]

In an additional action intended to cater to non-fishing visitors, the NPS began to beef up its interpretive program. Rangers at Brooks Camp had given occasional talks since 1956, but interpretation became far more visible with the presence of a uniformed ranger on the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes tour. The ranger provided a running commentary on the area's natural and geologic history to the bus passengers, and also led a hike down into the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. [94] The bus tour interpretation, of course, required additional staff. Therefore, what had been a two-ranger force in the late 1950s evolved, over the next ten years, into a staff of five or six. [95]

One of the most vexing problems that preoccupied both the concessioner and the Service in the 1960s was garbage disposal. In the 1950s cans and bottles had been routinely sunk in Naknek Lake or were buried at the edge of camp, and most other materials had been burned. [96] By the early 1960s, material waste and garbage were sent via barge to two open dumps on the shore of Naknek Lake. Bears eventually discovered their whereabouts, and because bears at that time were relatively uncommon at Brooks Camp, the concessioner often took guests to the dump to watch them. In 1965, however, employees began to complain of the bears' presence at the dump. [97]

The concessioner responded to the problem by covering over the beachfront dumps and replacing them with one located along the road headed to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes. Perhaps because of its relative inaccessibility, however, two new dumps were established within Brooks Camp. [98] The bears were soon attracted to the landfills. The Service and concessioner soon clashed on the issue. The Service's answer to the bear problem was to keep all food indoors until it could be hauled to the dump along the valley road. The concessioner, however, paid scant attention to the plan and took the attitude that it was the agency's responsibility to keep the bears away from the buildings, if necessary by relocating them. [99] NPS officials worked to educate all concerned to the nature of the bear problem, and by the end of the decade the problem had been overcome. Garbage was kept indoors until taken to the Brooks Camp dump, where it was incinerated. [100]

Petersen was correct in recognizing that the construction of more comfortable facilities, and diversifying the number of activities available, would attract a larger number of visitors. In 1962, before construction of the road to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, only 334 visitors were attracted to Brooks Camp. But the following year, with the road completed, more than twice as many came. That number continued to increase, and in 1968 some 1584 tourists visited Brooks Camp, almost five times as many as had visited six years earlier. [101]

Despite the increasing number of visitors during the 1960s, little construction took place after the 1964 erection of the Skytel at Brooks Camp and the guest cabins at Grosvenor Camp. Some felt that the existing level of construction was sufficient for the time being. As Senator Ernest Gruening remarked in 1965:

Katmai National Monument, in my judgment, needs very little further [development]. The lodgings and sustenance are adequately provided..., and with the... jeep trail, ...all visitors have access to that Valley which...was the basic reason for creating the Monument. [102]

The only reason the concession was not developed further, however, was that the NCA was not in a position to contemplate new construction. As Petersen noted in December 1965, "in order to place this Company in a position to finance acquisition of new modern jet equipment, it is necessary that we carefully review capital expenditures of a non-transport nature." [103] He requested a one-year contract extension, which was approved as Amendment No. 1 by John Walatka and Superintendent Oscar Dick on April 28, 1966. [104] By the fall of 1966, when negotiations had opened for the 1967 contract, a directive from President Lyndon Johnson imposed a one-year limitation on concession contracts. The Washington office of the National Park Service, therefore, prepared a second one-year extension, which was signed by John Walatka in December 1966 and NPS Assistant Director Harthon L. Bill in March 1967. [105]

Johnson's limitation was soon lifted, however, and by the summer of 1967 the NPS wanted to issue new, long-term concession contracts, both at Katmai and elsewhere in the system. [106] By this time, however, the concessioner had a whole new set of priorities to consider, because a proposed merger had been announced between Northern Consolidated Airlines and Wien Air Alaska. [107] The two airlines had begun merger talks in 1966 in order to obtain sufficient capital to purchase a fleet of Boeing 737-200 jets, and had announced the merger on March 15, 1967. [108] The effect of the merger announcement, as it related to the Katmai camps, was to table any new capital projects and to extract higher profits from the camps. The increasing number of visitors during the 1960s was a hopeful indicator of enhanced revenues, but a major stumbling block to greater development was the lack of easy access to Brooks Camp.

The access question had been festering for more than a dozen years. Since 1954, when plans for construction of a nearby airstrip had first been raised, the concessioner had intermittently tried to revive NPS interest in the project, particularly during the MISSION 66 construction program of the late 1950s and early 1960s. [109] The airline, which acquired its first Fairchild F-27B propjet in November 1958, hoped to establish Brooks Camp as a regular stop on flights between Anchorage and King Salmon. [110] When the MISSION 66 program statement was issued, agency officials promised that "an airstrip for wheel planes will be provided at a suitable location compatible with air currents, topography and landscape considerations near Brooks River Camp." But the Control Schedule for the program rated the construction of a $180,000 airfield as the Service's fourth (and last) priority. [111] Inertia prevailed. As an explanation for its lack of interest, agency officials backpedalled, noting that "since the concessioner has developed and is using an airstrip at its Kulik camp outside the monument, we do not consider another strip inside the monument to be of vital importance at this time." [112]

The Kulik Lake Airfield, meanwhile, was chosen instead of Brooks Camp as a scheduled stop on Anchorage-King Salmon flights. To accommodate the larger F-27s which this service entailed, the airline doubled the length of the Kulik airfield. [113] But this new service, which began in 1959, did not bring many new visitors to the camps, and by 1963 scheduled service to the airstrip was discontinued. Brooks Camp continued to be served by float planes from King Salmon; the Cessnas which had been relied upon were replaced in 1962 with a single six-passenger Pilatus Porter, "an excellent short take-off and landing airplane built in Switzerland." [114]

NCA officials, however, refused to drop the idea of an airfield at Brooks Camp. In 1967, the concessioner felt so strongly about the necessity of the airstrip that they tied its development to the creation of a new long term contract. This runway was ideally to be 5000 to 6000 feet in length (long enough to land the Boeing 737s the airline was intending to purchase), but at a minimum needed to be 3000-3500 feet long to replace its amphibious aircraft with Twin Otters or a Skyvan SC7. [115] The concessioner argued that an airstrip was needed for reasons of safety and reasoned that inasmuch as Alaska's other NPS units contained airstrips, Katmai should offer one as well. [116] In May 1967 officials rejected the airstrip idea yet again, reasoning that such a facility would change the wilderness character of the monument. [117] Not to be dissuaded, however, NCA officials made plain their demand for an airstrip and/or a road from Brooks Camp to King Salmon, and only "very belatedly" submitted plans for a 20-year contract. [118] McKinley Superintendent George Hall noted, after an antagonistic meeting with the concessioner, that

the airline business is the paramount consideration to this company and they wish to conform Katmai to their equipment. They are inclined to development of Katmai...as a resort to assure full airplane loads. Development of general [non-lodge] traffic to the Monument is not particularly part of their program.

Regarding capital improvements, the concessioner indicated that it would "invest substantially in the area if it warranted such action," but unless the airstrip question could be resolved it promised no new improvements. [119]

In January 1968, Acting Regional Director Raymond Mulvany deflected the airport issue by incorporating it within a larger planning framework. In a letter to Director George B. Hartzog, Jr., he noted that "it is apparent some long-range policy decisions will need to be clarified before the concessioner will talk about a new contract." With the understanding that a master plan study was programmed for the monument that summer, he recommended that a one-year extension of the existing contract be processed. [120] The Washington office, recognizing that the completion of a master plan would take more than a year, suggested a two-year extension, news of which was passed on to Ray Petersen on March 15. [121] John Walatka, probably with some reluctance, signed Amendment No. 3 to the 1961 contract on May 8, 1968; it was approved by Washington official Clarence P. Montgomery on June 25. [122]

Although the airfield and further camp construction were thus put on hold, the 1968 season culminated a decade which witnessed the construction of many of the major structural and transportation improvements seen in the park today. These improvements included the main lodge and guest cabins at Brooks Camp, Grosvenor Camp and Kulik Camp, the lodge at Nonvianuk Camp, the road to the Valley of Ten Thousand Smokes, and trails emanating from both Brooks Camp and the Windy Creek Overlook. The NPS also expanded an interpretive program during this period. Several improvements have been built since 1968, but the activities available to visitors have changed little since that time.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

katm/tourism/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 13-Oct-2004