|

Abiquiú On Saturday, October 19, 1867, the Santa Fé New Mexican ran the following brief notice. "THE CHURCH AT ABIQUIU BURNED—On Sunday afternoon last, about two o'clock, the church of Santo Tomas at Abiquiú took fire from a candle at the altar, and in a few minutes was entirely enveloped in flames. The church, save the walls, the altar furniture and everything pertaining thereto were totally destroyed. This church was nearly one hundred years old, having been erected in 1773." Surprisingly, the newspaper had the age of the structure correct. [1] Ever since the 1730s, settlers on the meandering Río de Chama 40 to 50 miles northwest of Santa Fe had tried to put down roots in the good bottomlands. Time and again they had been wrenched out by raiding Utes, Navajos, or Comanches. It was almost seasonal. One place, named for St. Rose of Lima, supported a scattered twenty families in 1744, but they could not hold out. Fleeing their homes and a chapel in 1748, the Santa Rosa people tried again in 1750. Under orders from Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín they returned reluctantly and laid out a 370-foot-square defensive plaza with the chapel in the center. It stood very close to the Chama's south bank. This time Santa Rosa de Abiquiú stuck. [2] To stabilize settlement in the area further, the same governor in 1754 decreed the establishment of the new pueblo and mission of Santo Tomás de Abiquiú for some refugee Hopis and for genízaros, those mainly non-Pueblo, "detribalized," and largely Hispanicized Indians and their descendants who made up a sort of servant class in eighteenth-century New Mexico. Although Vélez Cachupín again chose his name saint, as he had for the plaza of Las Trampas, both genízaros and Hispanos liked Santa Rosa de Lima better. "Therefore," Domínguez observed in 1776, "they celebrate the feast of this female saint, and not that of the masculine saint, annually as the patron." In Abiquiú today they celebrate both. The new community of Santo Tomás, about a mile and a half west of Santa Rosa on the same, or south, side of the Chama, sat on a broad hill with a varied view of distant blue peaks and red-streaked mesas. For Fray Juan José Toledo the view may have been the only earthly delight. Minister here between 1756 and 1771, he endured Indian raids, isolation, and witchcraft only to depart in disgrace, denounced to the Inquisition for allegedly having said that simple fornication was no sin. He did leave behind a convento and the walls of a church, "half way up on all sides," which formed the northern face of the enclosed hilltop plaza. For a time in 1772 a thirty-year-old Spanish friarrode out from Santa Clara to look after Abiquiú. The following year he moved into the mission convento. A vigorous sort who could not tolerate a job undone, Fray Sebastián Ángel Fernández finished the church of Santo Tomás with dispatch. In April 1776 Father Domínguez could scarcely say enough good about Fray Sebastián. Seeing the partially laid up structure, this exemplary pastor had "put his hand to it so firmly that he took the food from his own mouth and used his royal alms to finish the work and build what I now begin to describe." It was not overly large, about 22 feet (spreading to 38 at the transept) by 90 feet, but cruciform and with clerestory. Not once in his usually meticulous description did Domínguez resort to the adjectives "ugly" or "poorly made." He lauded the Abiquiú minister for his religious behavior and good stewardship, and for "the well-known disinterest with which he has conducted himself up to the present." A year later, Domínguez felt utterly betrayed. The impatient Father Fernández, over the opposition of his superior, had entered into civil contracts to build the churches of Picurís and Sandía, "giving for their cost to two different individuals of this kingdom mules, cattle, deerskins, and other things he has acquired by illicit trade, a business he has habitually engaged in since he has been in this kingdom." Worse, Fray Sebastián was trying to blacken Domínguez's good name. [3]

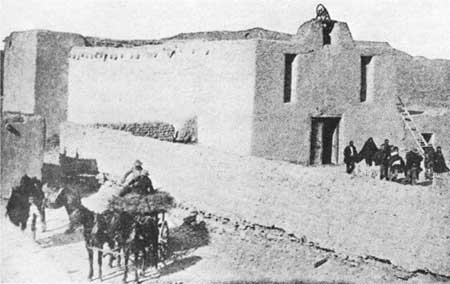

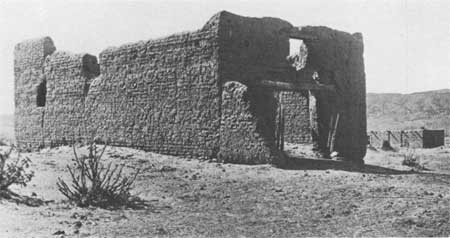

While he was at Abiquiú in 1776, Father Domínguez also inspected the Santa Rosa chapel. Not overly impressed, he compared it to a similar structure at Río Arriba, just above San Juan, which he reckoned looked like a wine cellar. He noted that the one at Santa Rosa had served for burials before there was a church of Santo Tomás. As an auxiliary chapel of the Abiquiú parish this building, or perhaps a somewhat larger replacement, continued in use through much of the nineteenth century. As late as the 1930s, its nave walls stood solid and high enough that it could have been reroofed. In the mid-1970s, as a bend of the Chama ate farther and farther into the leveled plaza, concerned locals moved to protect the site. Symbolically, on August 30, 1975, feast of St. Rose of Lima, when a Mass was celebrated next to the crumbling remains, landowners Alva A. Simpson, Jr. and his wife Anneliese deeded the shrine and 1.88 acres to the Archdiocese of Santa Fe. [4] Almost immediately, a model, professionally supervised community archaeological project got under way at the site. After the fire of 1867 the people of Abiquiú rebuilt their church of Santo Tomás and kept on celebrating the feast of Santa Rosa. Adolph Bandelier, who thought Abiquiú "quite a romantic spot" and the view superb, was there on the Día de Santa Rosa in 1885. Such a crowd had assembled that Bandelier found himself standing outside for Mass. At least he had his facts straight. "The old Pueblo of 'Genízaros,'" he wrote in his journal, "stood where the store and church are now, but the old church of Santa Rosa de Abiquiú is still two miles farther down, or east, of here." The rebuilt church in Abiquiú proper, first with traditional flat roof and, by the early twentieth century, with pitched roof and cupola, had a unique feature. Placed high, perhaps 10 feet off the ground, in the plain end-wall facade and reaching to the ceiling were two vertical, elongated niches or windows, each about 2-1/2 by 8 feet. Set wide apart, they looked like the stylized eyes of some giant jack-o'-lantern. [5]

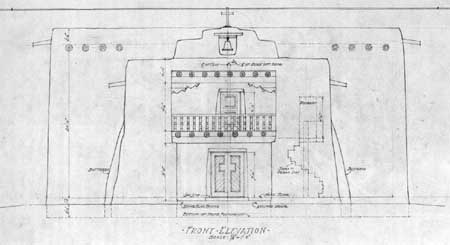

By the 1930s it was the consensus that Abiquiú needed a wholly new church. By then a mission of El Rito parish, Abiquiú was administered between 1932 and 1946 from sixteen miles away, by a remarkable German. Conscripted as a young priest into the kaiser's army to drive an ambulance, the Reverend William Bickhaus had later immigrated to the United States and the Archdiocese of Santa Fe. Influenced by Fathers Angellus Lammert, O.F.M., and Peter Kuppers, who had worked with the Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of the New Mexican Mission Churches, the determined Bickhaus sought and received advice and architectural drawings from John Gaw Meem in 1935. After Holy Week of 1937, the building of a new Santo Tomás began. First the old church—every vestige of the 1773 structure as rebuilt after 1867—had to be cleared away. The vigas would be reused as floor beams in a new dance hall. With the site leveled, a dispute arose over the orientation of the new church. Should it face south on the plaza as the old one had, or east as Father Bickhaus and the archbishop preferred? Even though the disagreement had temporarily wrecked community solidarity, partisan laborers began laying the foundation with an eastern orientation. Then, so one version of the story goes in Abiquiú today, a young member of the opposition "in an embittered state of mind over the setback suffered by his side, rammed his Model-T again and again into the freshly laid foundation until it crumbled beyond repair. The following morning, construction of the church started anew, but this time it was to face south as the old one had done. The Easterners had accepted the inevitable. With friendships renewed and cooperation restored, the mammoth structure [of 48,000 adobes] was completed in record time." [6]

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||