|

Santa Clara

As it stood in 1776, the church at Santa Clara was

the narrowest in New Mexico. It made Father Domínguez think of a

culverin, a long thin cannon. Its caliber, or width inside, measured

only 14 feet. Yet from the tall front door to the wall behind the altar,

including the transept (the handles or trunnions of the cannon), it

stretched out to 110 feet. The reason for its extreme narrowness,

Domínguez explained, was the lack of heavy vigas to span the

usual 20 to 25 feet. The Tewa pueblo of Santa Clara, 25 miles northwest

of Santa Fe, lay on the west bank of the Rio Grande, where big trees

were harder to drag down the rough canyons than from the high Sangre de

Cristos on the east side. To compensate for the thinness of the vigas

they were laid unusually close together across the nave, on centers of

21 or 22 inches, with little more than a foot of space between them.

Domínguez heard all about it firsthand from the missionary who

supervised the job.

Appearing older and more feeble than his fifty-one

years, Fray Mariano Rodríguez de la Torre related in 1776 how he

had built the Santa Clara church nearly twenty years before. A native of

Mexico City, enough in itself to endear him to Domínguez, Fray

Mariano had been in the missions not yet four years when in 1756 his

superior assigned him to this pueblo. Its post-Revolt church had melted

into a heap of rubble. There was nowhere to say Mass but "a very small

chapel, or shrine," which by the time of Domínguez's visitation

served "as a stable for dumb beasts that gather in it of their own

accord." So, in 1758, Rodríguez mobilized the Indians and local

Hispanos, without a levy, and set to work. He supplied the oxen that

were used to haul in the vigas, and paid for one of the animals killed

by an Indian in the process. He fed the construction crews gratis. And

they took advantage.

When the roof of the nave of the church was finished,

the Indians and the settlers left the rest up to the father alone and to

his industry. Therefore, what was necessary to roof the transept and

sanctuary was taken from his alms, and with this he roofed it. The

carpenters, in addition to being well paid, ate, drank, and lived in the

convent at the father's expense for a period of two months in the

winter, when the days are very short in this region. And since these

workmen were very gluttonous and spoiled (in this land, when there is

work to be done in the convents, the workers want a thousand delicacies,

and in their homes they eat filth), the gravy cost the father more than

the meat (as the saying goes). That is to say, they ate more and were

paid more than they worked. [1]

The strait and elongated church looked to the east,

with single-story convento, also the work of Rodríguez, huddled

against its sheltered south side. The nave, like the inside of a giant

casket, was all but unadorned, without even a choir loft: "soulless,"

Domínguez called it. In 1782 Fray Ramón Antonio

González had altar screens painted in tempera for the main altar

and for the side altars in the arms of the transept. The main one, which

drew praise even from Lieutenant Bourke ninety-nine years later, the

Indians of the pueblo paid for, while González donated the other

two. Showing some cracks in 1808, the building had been put back in such

good shape ten years later that Juan Bautista Guevara could find nothing

to complain about. In fact, for once he praised a Franciscan. The

ministry of Fray Francisco Bragado, including his school for boys, was

exemplary, at least in New Mexico. [2]

|

|

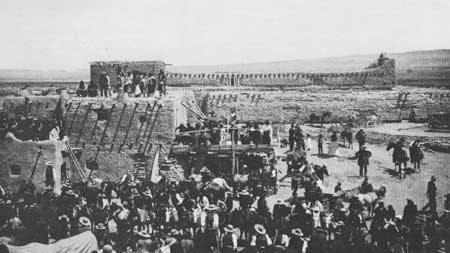

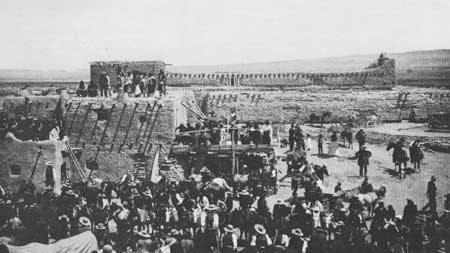

102. By the 1880s Santa Clara's narrow

church and its adjoining convento looked weathered and rundown. The

facade by Jackson about 1881.

|

Domínguez's varas and Bourke's paces were not

far off parity. The lieutenant, who put his three Santa Clara guides in

good humor by purchasing "freely of pottery, baskets and apricots" was

not favorably impressed by the pueblo's appearance in 1881. Of the

houses, "much worn at the corners," few stood more than one story tall.

Across their roofs to the north Bourke could see from the plaza the long

silhouette of the church.

My guides were anxious to show me the ruined church

of "Santa Clara" and under their care, I made a brief examination. It is

41 paces from main entrance to chancel, 5 paces wide, 18 ft. high, and

lighted by two square, unglazed windows, 8' x 5'. The ceiling is formed

of pine "vigas" with a "flooring" of roughly split pine slabs, upon

which is laid the earthen roof. In one arm of the transept, were a

collection of sacred statues, dolls, crosses and other appurtenances of

the church. The altarpiece, although much decayed, is greatly above the

average of the church paintings to be found in New Mexico. It is a panel

picture, with an ordinary daub of Santiago in the top compartment and a

very excellent drawing of Santa Clara in the principal place. The

drawing, coloring and expression of countenance are usually good and I

don't blame the Indians for being so proud of their Patroness. A

confessional and pulpit occupy opposite sides of the nave. [3]

Sometime before 1909 someone decided that the Santa

Clara church needed a peaked roof. Judge Prince believed that the old

vigas were removed and were not replaced. If so, the solid bond between

lateral walls was disjoined, allowing an outward thrust from the heavy

new roof. An engineer would have shuddered. The result was

predictable.

The church was so massively built that apparently it

would last for ages; but the very confidence thus inspired caused its

destruction. The spirit of innovation reached even to Santa Clara, and a

promise of a roof that would never leak was sufficient inducement for a

change. So the old timbers were removed and a modern roof placed on the

adobe walls; and alas! when the storm came, the great building which had

withstood the vicissitudes of centuries fell with a great crash as did

its sister church in Nambé; and one of the historic landmarks of

New Mexico was gone forever. [4]

|

|

103. A profile of the Santa Clara church.

Charles F. Lummis, 1880s.

|

In 1918 "a partial replica of this old church, but on

a smaller and simpler scale," went up. It too stood on the north side of

the pueblo outside the plaza. It was hardly half as long as its

predecessor and its walls rose not so high but neat and straight and

much thinner. Instead of a transverse clerestory light, difficult to

build and to keep from leaking, it had wooden-frame lateral windows. The

semicircular apse was a rather effective innovation. As a link to Fray

Mariano Rodríguez de la Torre's culverin church, the massive

front doors, each with its ten weathered panels, were salvaged from the

old and hung on the new. Since then, however, an expansion and face-lift

have disfigured the facade and the old doors are gone. [5]

|

|

104. The main altar screen, constructed in

1782 around the painting of St. Clare, was still in place in 1899.

|

|

|

105. George H. Pepper caught the Santa

Clara church with its pitched roof about 1905..

|

|

|

106. The church at Santa Clara a

few years later.

|

|

|

107. The replica church under construction,

August 12, 1918.

|

|

|

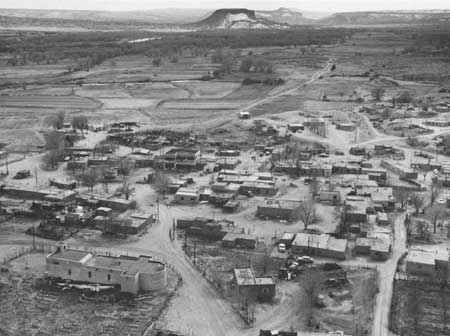

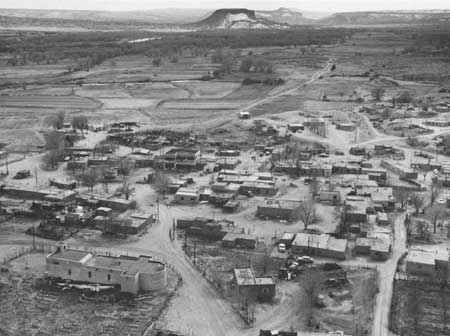

108. Santa Clara pueblo, 1964. The 1918

church (lower left), remodeled and expanded in front, looks like this

today.

|

Copyright © 1980 by

the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from

this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by

the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner

without the written consent of the author and the University of New

Mexico Press.

|

Top

Top