|

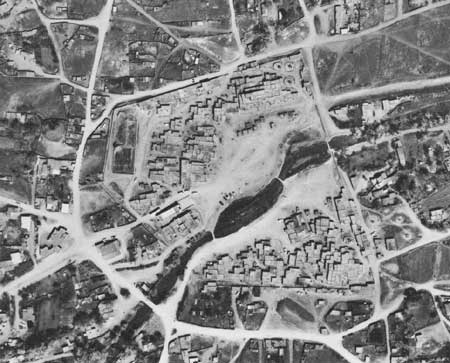

Taos One duty of New Mexico's Spanish governor was to make an inspection tour of the colony. At each major settlement he reminded residents that they were vassals of His Most Catholic Majesty, he took a census and assessed military preparedness, and he held court. Anyone injured or offended by his neighbor was invited to come forward and receive the benefit of royal justice. On July 28, 1733, at Pecos, a pueblo known for its carpenters, several Indians appeared before Governor Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora with claims. The first had made a door for a soldier of the Santa Fe presidio. The price, one horse bit, had not been paid in more than twelve years. The plaintiff was given a large Mexican hoe. Another, who had been relieved by a Hispano of one red roan he-mule, received a musket. Then came four Pecos men: "Alonso Benti, Juan Diego Guojechinto, Diego Chumba, and Antonio Chunfugua, Indian carpenters of said pueblo, ask and claim of the Reverend Father fray Juan José de Mirabal, [former] minister of the pueblo of Taos, twenty-four trade knives, six each one, for the work they did on the church carving timbers, now more than ten years ago." The governor assured them that the Reverend Father would be notified. [1] In 1722 young Fray Juan José Pérez de Mirabal had drawn as his first New Mexico assignment the formidable Tiwa pueblo of San Jerónimo de Taos. Previously, in 1639 and 1680, the Taos Indians had risen, martyred their missionary, and ravaged churches. After the 1696 revolt Diego de Vargas had found them using the shell of their church as a corral. He told them to muck it out and repair it. Fray Juan Álvarez, relying on his stock phrase to describe the situation in 1706—"The building of the church has been begun."—meant that something was serving until a proper church could be built. Whether Pérez de Mirabal started with wholly new foundations or incorporated parts of a previous structure, he laid up a truly proper church. Fifty years afterward Father Domínguez could read from below the inscription on the beam holding up the clerestory: "Fray Juan Mirabal built this church to the greater honor and glory of God. Year of 1726." He meant it to last. The walls, Domínguez said, were very thick, containing within them a simple nave 22 by 116 feet. The unusual, unbalanced facade, looking south, had to the left of the door a huge adobe base from which a bell tower rose. Domínguez thought the effect hideous. The belfry, entered via the church roof, commanded a fine view in all directions through four large openings constructed with true arches, evidently not so rare an occurrence in New Mexico's adobe churches as has been imagined. The roof had a good parapet "and embrasure for defense." In 1776 the heavy-built structure doubled as a fortress against Comanche attack. It stood west of the two main several-tiered house blocks, near the temporary homes of some three hundred refugee Hispanos, and just inside the protective wall that enclosed the pueblo. The scene reminded the Franciscan visitor of "those walled cities with bastions and towers that are described to us in the Bible." [2] Inside the fortress-church Domínguez found numerous furnishings provided by the artist-friar Andrés García, from altar screen to wooden flooring. The santos García had made with his own hands. "And it is a pity that he should have used his labor for anything so ugly as the said works are—as bad as the ones mentioned at [Santa Cruz de] La Cañada." Fray Andrés, it appeared, had turned the convento, a hollow square of rooms on the church's east flank, into a woodworking shop. According to Domínguez, "Father García wrought such havoc in this convento that it has been necessary for the careful to restore it." Fray Andrés de Claramonte, resident minister between 1770 and 1774, had done his best, but by 1808 only three rooms remained livable. [3] A sixteen-year New Mexico veteran and former custos, Fray José Benito Pereyro took over the mission and pueblo of San Jerónimo de Taos in 1810 and stayed until 1818. He completely revamped the convento, which was again considered unlivable twenty years afterward, and he made sundry additions to the church's inventory. Pereyro's pueblo flock numbered something over five hundred Taos Indians. But he was minister as well to nearly three times as many Hispanos who had settled for miles up and down the gray-green Taos Valley. Their two largest communities were Fernández de Taos, ancestor of the arty municipality of Taos proper, and Las Trampas de Taos, today's Ranchos de Taos. The first had received from the bishop of Durango a license, dated November 18, 1801, to build the church of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. The second still did not have a church when Pereyro arrived. The "license to build a chapel at the settlement of San Francisco de las Trampas," or Ranchos de Taos, bore the date September 20, 1813. "This temple," Pereyro noted himself, "was constructed at the cost of the Reverend Father minister fray José Benito Pereyro and the citizens of this plaza." It was probably up by late 1815 when Pereyro petitioned Durango for permission to bury inside the structure. If the Franciscan expected accolades from Durango's Juan Bautista Guevara for his good works, he should have known better. The same day the inspector went through the church of San Francisco at Ranchos, June 13, 1818, he roasted Pereyro for "the deplorable state of abandonment" that existed in his parish. [4] After 1826, when the rapidly growing parish was secularized, the priest no longer lived in the convento at Taos pueblo. Don Antonio José Martínez, the native-born phenomenon who began his long tenure that same year, took lodging in Fernández de Taos. Bishop Zubiría confirmed the arrangement in 1833. Martínez was using Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe as his parish church "because of the unhealthfulness of the priests' house at the pueblo of San Jerónimo de Taos." [5] Educator, printer, legislator, Mexican nationalist, Padre Martínez watched the Taos Valley filling up. He warned of the danger in Anglo-American immigrants—mountain men, merchants, landowners, distillers. He predicted a United States takeover, and he was right. Just what part, if any, he played in the resistance of 1846-47 may never be known. He was at home when the mob broke into the Taos residence of Governor Charles Bent and scalped him in front of his wife and children. Other Anglos and Anglo-sympathizers died that day in Taos, to the north at Turley's Mill, and over the mountains at Mora. In response, on January 23, 1847, Colonel Sterling Price marched north from Santa Fe with three to four hundred men. Fighting two inconclusive actions en route, the American force, numbed by snow and the intense cold, came in view of Fernández de Taos on February 3. The locals had fallen back on the fortified pueblo of Taos, there to make a final stand. Pressing on, Price's men were met by "a most unearthly yell. We had but a few rounds of ammunition with the guns," wrote Lieutenant A. B. Dyer, the artillery officer, "and we entertained them for a little while with a few shots and shells." Then the Americans withdrew to the town for the night, "a busy one for me," Dyer recalled, "as I had all my ammunition to prepare and arrange for the next day's fight, which we were satisfied would be a hard and bloody one." The 4th dawned brilliant. Price's army, swollen by reinforcements to nearly five hundred, moved out across glaring snow-blanketed fields. Ordering two bodies of troops around behind the pueblo to cut off escape to the mountains, the commander positioned two batteries of artillery, one 300 yards to the north, the other 260 to the west. At 9:00 A.M. the guns opened fire. "The strongest point," noted Lieutenant Dyer "was the church and the enemy seemed disposed to defend it at all hazards. The 6 pdr. [pounder] and 2 Howitzers were so placed as to sweep all of the faces. The other two to play in front and on the neighboring buildings." Seeing that the artillery after nearly two hours had not breached the church of San Jerónimo, the anxious Colonel Price ordered a charge against the north and west walls. Axes were used in a futile attempt to break through. The defenders' deadly fire claimed Captain John H. K. Burgwin and a half-dozen others. "During all this time," Dyer reported,

Two months later, during a dull session of the resistance leaders' trial for treason, Lewis H. Garrard, a wide-eyed teenager who had ridden with a party down from Bent's Fort too late for the fight, walked the two and a half miles from town across clear-running acequias and greening fields. He and his companions imagined the action. "'The mingled noise of bursting shells, firearms, the yells of the Americans, and the shrieks of the wounded,' says my narrator, an eyewitness, 'was most appalling.'" Still, young Garrard wished he had been in on it.

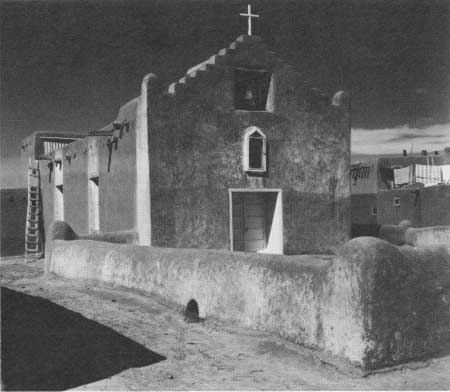

Almost before the smoke cleared, a new, smaller church of San Jerónimo had risen, not from the ashes of its fallen predecessor but a hundred yards to the southeast, fronting on the pueblo's main plaza. The date of its construction remains a puzzle, although "about 1850," during the tenure of the famed Padre Martínez, seems a safe guess. [8] In use longer now than the old church at the time of its bombardment, veteran of numerous renovations and a bewildering series of facade changes, the "new" San Jerónimo still serves today. But the old is not forgotten. Two and a half centuries after Father Pérez de Mirabal had his name carved on the clerestory beam, portions of the walls and buttress-tower endure, framing the crosses of recent burials within. The shell of the former San Jerónimo also still serves. [9]

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||

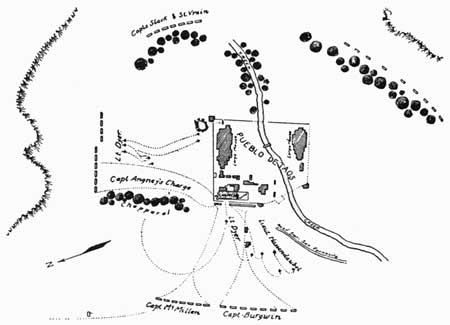

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||