|

Gailsteo Boasting to the king of his recent accomplishments, Governor Francisco Cuervo y Valdés asserted in April 1706 that in addition to founding the new villa of Albuquerque he had also resettled the old pueblo of Galisteo, 20 miles south of Santa Fe. Alone in the broad bowl of the Galisteo Basin, where there had been half a dozen pueblos in the previous century, this settlement would guard the soft underbelly of Santa Fe, defensively speaking. One hundred and fifty families of the Tano nation, who had been dispersed "in other pueblos, ranches and frontier places, poorly and unhappily," now had come home. "The church is newly rebuilt, as is the convent." The patroness, a constant reminder to the people, was Nuestra Señora de los Remedios, the very image reconqueror Diego de Vargas had borne on his battle standard in 1693 when he drove the Tanos out of Santa Fe. "Today," Cuervo assured the king in 1706, "they are very happily congregated in their [own] pueblo." [1] Seventy years later Father Domínguez found no happiness. The pueblo's population was down to 41 families with 152 persons. Only fear of the government, said Domínguez, kept them from abandoning the place. They had suffered droughts and famine, and since the 1740s the assaults of the Comanches. They lived, as Fray Manuel Trigo put it in 1754, under "the barbarian hammer." Not that these Tanos were cowards. To the contrary, declared Trigo, who was present during an attack when "boys of fifteen scaled the walls, the gates being shut, so as to be able to give the enemy a warm welcome with arrows and slings." Unintentionally, perhaps, the Galisteo Indians put the fear of God into Bishop Tamarón as he and his party approached the pueblo in 1760. Riding full tilt across the hills to welcome the prelate, they were mistaken for Comanches. The bishop spurred his horse for safety. "Galisteo," he noted in relief, "is surrounded by adobe walls, and there is a gate with which they shut themselves in. Here is the usual theatre of war with the Comanches, who keep this pueblo in a bad way." [2] It was so bad in 1776 that Domínguez wanted to cry. The condition of church and convento conjured up

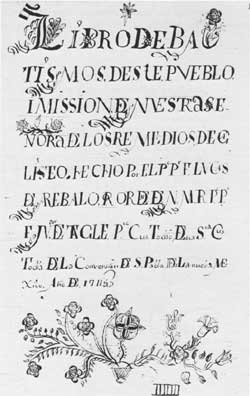

The convento on the north side of the church had eight rooms, all in ruins. "It is so uninhabitable," bemoaned Domínguez "that to live in it is to enter expecting death and to remain buried there as soon as one sits down, because it is so near to falling." Like Pecos, the mission at Galisteo had no resident minister. Instead a friar ventured out of Santa Fe from time to time, or the people of Galisteo went to the villa. Already so many things listed on the inventories were missing that Domínguez packed up the remaining vestments and removed them to Santa Fe for safekeeping. If he heard it six or ten years later, the observant Franciscan would not have been surprised by the news that Galisteo finally lay deserted. The smallpox epidemic of 1781 may have been the final blow. Early the following year Galisteo's marriage and burial books were reassigned to Pecos. Then, too, after Governor Juan Bautista de Anza achieved a lasting peace with the Comanches in 1786, there was not so great a need for a defensive outpost in the Galisteo Basin. On a 1788 census Galisteo was not even listed. The Tanos had gone. [3] Poking around the ruin in 1882, Adolph Bandelier noted "many traces of combustion." Even the potsherds looked charred and burned. In places the foundations, partly of stone and partly of adobe, still showed. He reckoned that the pueblo had stood only two stories high but was considerable in extent. He saw no evidence of kivas. Like Domínguez, he mentioned the prominent ragged crestón, or volcanic dike, that lay just south of the pueblo like the endless backbone of a partially submerged dinosaur. [4] Before archaeologist Nels Nelson began a cursory four-day excavation of the site in 1912, "the presence of pueblo remains would hardly have been noticed by anyone coming near, unless he had passed directly over the spot." The immediate surroundings Nelson thought "dreary and barren." He, too, found no kivas. He did not locate the church either, but he did dig partially a 13.5 by 16.5-foot room he believed to be part of the convento. Domínguez gave no measurements at Galisteo, but his location of church and convento at the southwest corner of the pueblo wall is confirmed in Nelson's diagram. At the other three corners of the wall in 1776, the Franciscan had observed "three fortified towers"—sure signs of the function of the place. [5] With ill-starred Galisteo, Fray Francisco Atanasio Domínguez had terminated his singular survey of the missions of New Mexico, 1776. If he did not wish to end on an unhappy note, his honesty, as usual, got the better of him. There was no avoiding it. He had "found the last pueblo and mission caught on a reef of misfortunes." And, sure enough, it was the first to break up. Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||