|

Pecos The destruction of the mammoth church at Pecos in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 must have been a grand show. The Pecos Indians later blamed the Tewas. Whoever threw it down, they did so with a vengeance. As a start they probably heaped piñon and juniper branches and dry brush inside the cavernous structure. Then they set it afire. "When the roof caught and began burning furiously 'a strong draft was created through the tunnel of the nave from the clearstory window over the chancel thereby blowing ashes out the door.' It was like a giant furnace. When it died down, the blackened walls of the gutted monster still stood. To bring it low Indians bent on demolition clambered all over it, like the Lilliputians over Gulliver, laboriously but jubilantly throwing down adobes, tens of thousands of them. Unsupported by the side walls, the front wall toppled forward facade down, covering the layer of ashes blown out the door." [1] Pecos, teeming, multistoried, stone-and-mud citadel at the gateway between Pueblos and Plains, home to nearly two thousand souls, had deserved, in the opinion of Fray Andrés Juárez, the grandest Christian monument in the kingdom. And thanks to Juárez, a most effective missioner, that was just what the Pecos Indians raised up between 1622 and 1625.

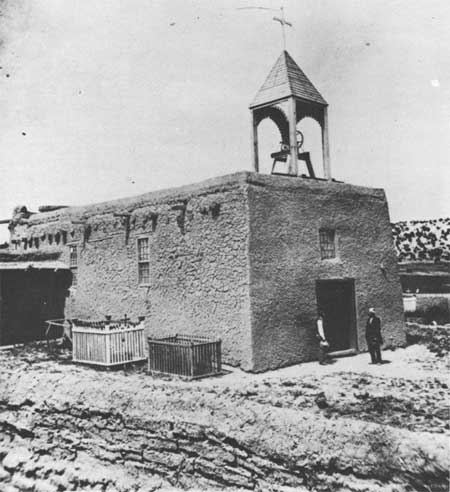

Like a counterbalance, the church of Nuestra Señora de Porciúncula sat at the opposite end of the same narrow, flat-topped ridge from the main pueblo—a prudent 800 feet away. It looked eastward toward the Pecos River and had a partially two-storied convento on the sheltered south side. It was like no other church in New Mexico. The fabric had demanded 300,000 adobes. Even the hulking structure built at Ácoma in the succeeding decade would have fitted inside. Containing some 5,300 square feet, compared to Ácoma's 3,600, the huge continuous nave and sanctuary at Pecos tapered from 41 feet at the door to 37-1/2 at the chancel steps. Outside, it was even more of a marvel. The clifflike 8- to 10-foot-thick lateral walls featured closely spaced ground-to-roof buttresses. Six towers rose above the roofline. "Architecturally it was unique, a sixteenth-century Mexican fortress-church in the medieval tradition rendered in adobe in the baroque age at the ends of the earth." [2] Diego de Vargas in 1692 did not mention the great ruinous mound that had been the Pecos church. Two years later Fray Diego de Zeinos persuaded the Indians to level part of the mound and construct a temporary church that utilized the massive standing north wall of the earlier convento. Facing west, the reverse of Father Juárez's church, it was only 20 by 60 or 70 feet inside, really "a chapel, not large but decent and fitting for celebrating the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass." Late in 1696, while Pecos auxiliary troops helped Governor Diego de Vargas quell another rising of the northern pueblos, Custos Francisco de Vargas remodeled the Pecos "chapel." The governor was favorably impressed.

By the turn of the eighteenth century, the population of Pecos was down by more than half, to eight hundred or so. Still, the temporary church was too cramped. Custos Juan Álvarez said of Pecos in 1706, as he did of fifteen other missions, that "they are beginning to build the church." If his statement was accurate, the job dragged. Domínguez, counting in 1776 the well wrought roof vigas, noted a terse inscription in Latin "on the one facing the nave: Frater Carolus. The inference is that a friar of this name was the one who built the church, but it is impossible to identify him since the individual is not identified by his surname." He was Fray Carlos José Delgado, who arrived in New Mexico in 1710 and labored for forty years, a singularly apostolic Spaniard in a less than apostolic age. Delgado signed the Pecos books between August of 1716 and October of 1717, and he filled the margins with garlands of odd snowball-like flowers. Whether the artist-friar was indeed the builder or simply finished the structure in 1716-17, the new church rated from the irrepressible Fray Juan Miguel Menchero the adjectives "beautiful and capacious." Father Domínguez thought the interior "rather pleasant," and from his lack of derogatory remarks he must also have considered it rather well built. Cruciform in plan, with a twin-towered and balconied facade looking west, it sat entirely on the leveled building platform thrust up by Andrés Juárez's much larger crumbled temple. That fact escaped Domínguez in 1776, and everyone else until 1967. [4]

Custos Pereyro reported in 1808 that church and convento were "not up to standard," but he did not elaborate. The pueblo itself was moribund. Reduced over the years by the ravages of disease and warfare, rent from within by dissension—the community's "fatal flaw"—Pecos had lost its reason for being. After the settlement of San Miguel del Vado in 1798 downriver to the east, it no longer enjoyed its historic advantage as gateway to the Plains. Forty years later, in 1838, the last of the Pecos, seven men, seven women, and three children—as one version has it—quit the place and went to live at Jémez, the only other pueblo that spoke their Towa language. That left the remains of Pecos mission and pueblo to local farmers and herdsmen, curious Santa Fe traders, vandals of every stripe, and eventually to the archaeologists. [5] In ruins the fame of Pecos grew. Because this deserted and moldering city was so impressive in decay, and because it loomed majestically in plain view from the Santa Fe Trail—and later from the railroad, whose public relations people put up a huge sign—visitors resorted to all manner of tales to explain its demise. The result was a blend of Pueblo mythology up from Mexico and rampant nineteenth-century Anglo-American romanticism. Lieutenant J. W. Abert, passing through on September 26, 1846, was among the more restrained contributors.

Twenty-four years later Adolph Bandelier discovered Pecos. "I am dirty, ragged & sun burnt," he wrote from a ranch in the vicinity only two weeks after his advent in the Southwest, "but of best cheer. My life's work has at last begun." He spent ten delightful days in 1880 pacing off the ruins, picking up sherds, taking notes, and talking with the locals. The paper he dashed off for the Archaeological Institute of America directed attention to Pecos and the Southwest as prime fields for excavation. It was, of course, the pueblo itself—pure, prehistoric, aboriginal—that entranced Bandelier and the others. The church was incidental, but not without interest. In his report, Bandelier told in passing what was happening to it.

In 1915 the Museum of New Mexico entered into an agreement with the Phillips Academy of Andover, Massachusetts, for an archaeological excavation. "No hampering conditions were imposed," wrote field director Alfred Vincent Kidder, "but the Regents [of the Museum] requested that the old mission church, greatly damaged by the weather and by vandalism, and in immediate danger of entire collapse, be so repaired and protected that no further harm should ensue." [8] That same year, while Kidder launched a decade of work at Pecos pueblo that would lay the ground rules for Southwestern archaeology, Jesse L. Nusbaum and his crew cleaned tons of debris out of the roofless, sadly weathered church and shored up undercut walls with massive cement footings. Museum Director Edgar L. Hewett admitted that this was only "an emergency job, not expected to be permanent." In 1939 and 1940 William B. Witkind, directing boys from the Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Youth Administration, redid much of the earlier work using iron tie rods, wire, and tens of thousands of adobes. At the sanctuary and transept end the stabilized church walls still stood over thirty feet high, inviting the imaginative visitor to reconstruct with his mind's eye the grandeur of the original Pecos church. [9] But they were all fooled—Bandelier, Kidder, Hewett, George Kubler, the lot. All believed that what they saw was the pre-Revolt church—albeit repaired or rebuilt—the "most splendid temple of singular construction and excellence" that Fray Alonso de Benavides had exalted in 1630, the magnificent, six-towered structure extolled by Fray Augustín de Vetancurt, with walls "so thick that services were held in their recesses." If these pious chroniclers had got carried away by their own zeal, that was expectable. The Pecos church, judging from its visible ruins, had been impressive, but not as extraordinary as the missionaries made out.

In 1965 Pecos became a National Monument. Two years later as part of the renewed excavation and stabilization of the mission complex, Park Service archaeologist Jean M. Pinkley was looking for a wall of the porter's lodge as described by Domínguez. Her trench ran into a massive masonry footing instead. She had hit upon the base of the southwestern tower of Fray Andrés Juárez's extraordinary monument. By the time she traced it out, she had not only vindicated the pious chroniclers but had begun to sound like one herself. Jean Pinkley died in 1969 before she had entirely finished her project or compiled a report on her findings. In 1972, in the preface to a new printing of Relgious Architecture of New Mexico, George Kubler credited Pinkley with a major archaeological discovery. The Pecos church that Juárez built, Kubler asserted, "now emerges as the 'prime object' in seventeenth-century New Mexico." Reemerges would have been a better word. Uncovered and stabilized, the immense foundations today speak for themselves. [10]

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||