|

Isleta On the west bank, "about a musket shot and a half" from the Rio Grande, only 13 miles south of Albuquerque, lies the Southern Tiwa pueblo and mission of San Agustín de la Isleta. "It is called Isleta [little island]," Bishop Tamarón explained in 1760, "because it is very close to the Río Grande del Norte, and when the river is in flood, one branch surrounds it. It is not innundated because it stands on a little mound." [1] Today Isleta is the largest of the pueblos on the river, and probably the best known. Its church, despite a rich history of alterations, has an excellent claim on the title "oldest in New Mexico," embodying as it does portions of foundation and walls built in or about 1613. The pueblo's proximity to Albuquerque has accorded it maximum exposure. Feast-day ceremonial or hotly contested election, remodeling of the church or development of a pickle plant—such Isleta doings are reported regularly in Albuquerque newspapers. Once recently, when the Isletas reasserted their ownership of the church in a most dramatic way, they made news nationwide. In the penetrating cold of a December night Governor Antonio de Otermín had advanced on Isleta at the head of seventy men. He may already have sensed that his attempt to reconquer the Pueblos only a year after the Revolt of 1680 was ill-timed. At dawn he could see smoke rising above the houses. At least Isleta was peopled. After token resistance they let him enter. More than five hundred souls having assembled, the governor—seeing holy temple and convent burned and ruined, the crosses thrown down throughout the pueblo, and a cowpen inside the body of the church—was very indignant, and ordered the cows turned into the fields and gave the Indians a severe reprimand." They told him that they were not to blame, that the Northern Tiwas and the Tewas had come down and desecrated the church. When he pulled out four weeks later, Otermín took several hundred of these Isleta people "under his protection" to settle south of El Paso. In 1692 Diego de Vargas found the place desolate and in ruins, "except for the nave of the church, the walls of which are in good condition." [2]

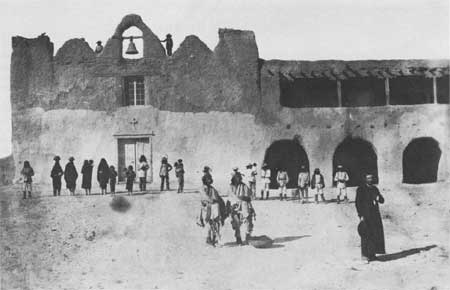

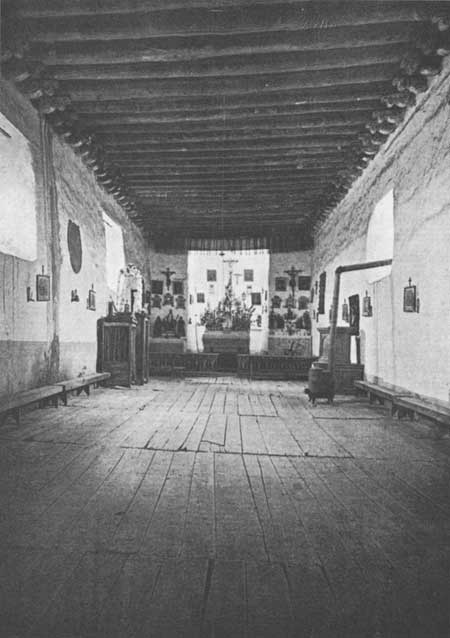

Those same sturdy walls served again when Father Custos Juan de la Peña, who had gathered up numerous dispersed Tiwa families, "re-established and refounded the old pueblo and mission of San Agustín of Isleta with the consent and aid of the governor at the beginning of January, 1710." Fifty years later Tamarón dismissed the Isleta church as "single-naved, with an adorned altar." It looked to the south on a very broad plaza. Already by 1776 Father Domínguez noted the scattering of individual dwellings beyond the plaza and as a result the more Spanish appearance of Isleta. Inside the dim, long, earth-floored church, Domínguez was reminded of "a rather dark wine cellar." He must have been tired. Moving on to inspect the large two-storied convento abutting the east wall, with its unique arched portico giving on the plaza, the incorruptible Franciscan inspector began to lose his patience. "The plan," he despaired, "is so intricate that if I describe it, I shall only cause confusion." Furthermore, it was badly laid out. Where did the stairway to the convento's entrance begin? In the corral no less. [3] Domínguez gave only the barest details of the facade in 1776: a two-leaved door three varas high by two wide, a window above looking out from the choir loft, and "on top of each of the front corners of the church" a turret. Ninety-one years later, a fine photograph, by famed Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner or by his companion Dr. William A. Bell (out West on a railroad survey in 1867), exhibited some changes—but nothing compared to what lay ahead. Behind an interesting lineup of Isleta people with their handsome, unidentified priest (who may be the Rev. J. B. Brun), and centered over the door and choir loft window, rose a high-arched bell gable with one large bell. On each side, half as tall, was an adobe peak. Outside these and rising barely higher, on top of buttress-towers flush with and expanding the facade, sat blocklike structures of adobe, weathered-down versions, it would seem, of Domínguez's turrets. From the edge of the tower on the west to the east end of the convento, with its three heavy arches on the ground floor and its long mirador above, the facade of the building extended on a single plane. Not many months before, it had been mud-plastered halfway up across the entire expanse, leaving a horizontal line that looked like the high-water mark after a flood. [4]

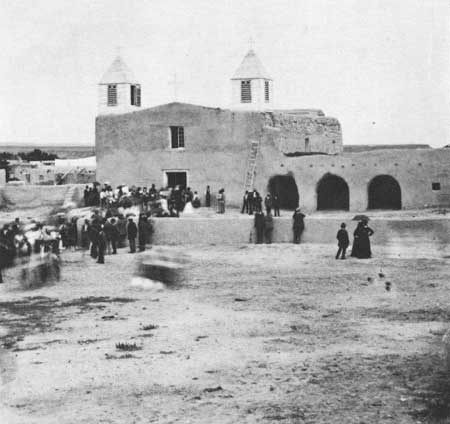

By 1881, when Lieutenant John G. Bourke sketched it and Ben Wittick photographed it, the face of the Isleta church had changed its expression. Bell gable and peaks, as well as the second story of the convento wing, were gone. Two boxy, louvered wooden belfries topped by pyramidal roofs and botonee crosses perched awkwardly at the corners with only a low pitched pediment and a larger cross between. Bourke, who thought Isleta looked "very much like a Mexican town," happened to be here on November 2, All Souls Day, the traditional time in the pueblos of New Mexico when fruits of the harvest were offered symbolically to the dead and afterward heaped in the priest's storeroom for his sustenance. Bourke set the scene.

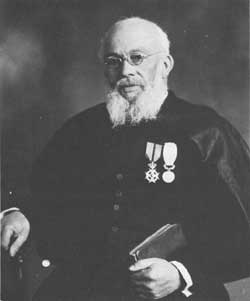

In May of 1891 the amiable, well-fed Rev. Antonine Docher came to Isleta to stay for thirty-five years. What he did to the church, a sacrilege to the adobe purist and to the non-purist a delightful flight of fancy, made the oldest also the most distinctive. Before Docher's advent the west wall had been punctured by two large windows and buttressed between. In the late 1890s, as the last two arches—all that was left of the earlier convento—melted down, the Frenchman began his gradual transfiguration of the facade. First, he had a couple of truncated buttresses built in front of the towers, as if to prevent the latter from pitching forward, and between them he had the thickness of the front wall doubled, up to the height of the door lintel. These alterations broke up the old single plane and at the same time provided a platform for a future balcony. A weathered vestige of the old convento slanting upward from the ground toward the east belfry and an additional buttress pushing on the west side gave the facade a new slope-shouldered look. About 1910 the inevitable pitched roof of corrugated iron went up. After that, there was no stopping the French priest.

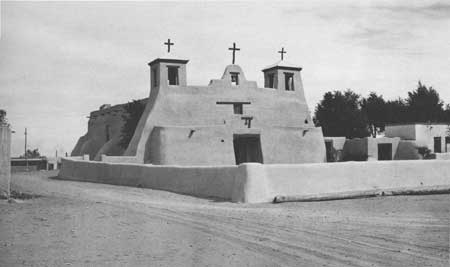

By October 20, 1919, the grand day King Albert of Belgium and his queen visited the church, Father Docher was ready. Aside from the flags and bunting, the facade now featured a broad, roofed balcony or veranda and two of the most outlandish belfries in all Christendom. From fancy boxes, displaying now two louvered panels per face except on the side where they were joined to the pitched roof, rose one big central spire surrounded by four little ones, each surmounted by a cross. Counting the cross on the gable at the front and the one on the auxiliary belfry roosting at the rear, there were now twelve crosses in all on the roof of the church at Isleta, surely no coincidence. [6] Time and the elements wore hard on Father Docher's embellishments. The eight small spires came down first, then the lonely auxiliary belfry and the elevated veranda with its sloped tin roof. Straight on, the effect was starkly incongruous. There was no other facade like it. The weathered wooden superstructure appeared to float above like a fancy hat on the head of someone whose face had been heavily packed with white plaster to-make a mask. By the late 1950s, however, the church was due its periodic restoration, which this time happened to coincide with the controversial ministry of the outspoken German-born Msgr. Frederick A. Stadtmueller. Work commenced in 1959. The Santa Fe architectural firm of McHugh and Hooker, Bradley P. Kidder, and Associates was called in by the archdiocese after Stadtmueller had committed himself to major changes. Off came Father Docher's pitched roof and his fairy-tale steeples. Once again the light of day shone directly through the clerestory upon the altar. Gone were the millwork and louvers, and in their place stood good solid concrete-block belfries much more in keeping with the massing of the building. In the east one Monsignor Stadtmueller had a new bell from Cincinnati rigged to ring electrically. Inside, much of "the nineteenth-century clutter" was removed. Replastered walls and inconspicuous panel lighting now showed to advantage the old paintings. Stout-heartedly, the remodelers confronted another relic of the place—a long-dead but reportedly well-preserved Franciscan who rose periodically with the high water table. In August of 1959 the log coffin of Fray Juan José Padilla, which had worked its way to the surface every generation or so after its burial in the sanctuary in 1756, was reopened in the presence of a pathologist who pronounced the remains not at all unusual. Documents to that effect were added to others of earlier examinations in the coffin and Father Padilla was put back to rest beneath a substantial concrete floor—"this time for good." [7]

Monsignor Stadtmueller who did not hide his belief that one could not be both a good Roman Catholic and a pagan, had angered some of the Isleta people. They charged him with gross disrespect for "the Indian way of life." By early 1964 a petition for Stadtmueller's removal was circulating. One visible bone of contention was the 30-foot circular slab of concrete poured in the churchyard during the 1959-60 renovation and designated by the priest a dance platform. The Isletas whose ceremonial dances were meant to take place on Mother Earth, refused to use it. Matters had come to such a pass by June of 1965 that the pueblo's Governor Andy Abeita threatened to evict Stadtmueller if he did not leave. Stadtmueller did not. The photo of Abeita leading the handcuffed pastor of Isleta from the rectory on June 27, 1965, appeared in Life. The following Sunday, July 4, Archbishop James Peter Davis celebrated a farewell Mass at Isleta and had the church locked up. The night of the government of an Indian pueblo to determine its own internal affairs—which included ownership of the church property—had run head-on into a Roman Catholic prelate's right to assign the priest of his choice to whatever parish. Deep rifts within the pueblo complicated the issue, as did the efforts of both sides to sort out what belonged to Caesar and what belonged to God.

Nine years later, in 1974, Archbishop Robert F. Sánchez reelevated Isleta to parish status, and a resident priest, the first since Stadtmueller, moved back into the rectory. At Christmastime the new pastor announced that he was in accord with a recommendation of the pueblo council. The concrete slab would be removed. Except for the walks, the churchyard today is mostly dirt. Other than that, Stadtmueller's renovation of "the oldest church" looks as it did in 1960. In that year architectural historian Bainbridge Bunting had lamented the building's loss of distinctiveness, overstating his case as is a professor's wont. "Without a blush of embarrassment," he wrote, "this new facade might appear on any church in any neighborhood in any community between the Panhandle and Los Angeles—an interchangeable architecture for an interchangeable man in an interchangeable society." [8]

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||