|

Zuñi During the eighteenth and part of the nineteenth century, the isolated westernmost "Christian outpost" at Zuñi was the Siberia of New Mexico. Any friar who appeared in Santa Fe without his superior's permission and good reason, warned Fray Juan Miguel Menchero in 1731, would serve six months at the mission of Zuñi for the first offense, and for the second, arrest and summons before the custos. A common sentence meted out to New Mexican citizens of the time was military service on the Zuñi frontier. Because of its great distance from any other settlement—the pueblo lay 75 miles beyond Ácoma and 125 miles west of the Rio Grande—and because of the almost constant threat of attack by Gila Apaches and Navajos, the Franciscans considered Zuñi a hardship post. A missionary should not have to minister here by himself. He should have a companion, and both should receive an annual royal allowance of 450 pesos, nearly 40 percent more than the standard 330. Zuñe was also the largest pueblo, with 1,617 souls in 1776 more than the villa of Santa Fe. In addition, the people here spoke Zuñian, a language unrelated to any other in New Mexico. Yet from time to time there were friars who preferred to labor at the pueblo and mission of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Zuñi, to take up a heavier cross. Four days by trail to the northwest stood the mesatop pueblos of the Hopis, apostates since 1680. A sure reward in heaven awaited the Franciscan who would lead these strayed souls back onto the path of salvation. Other trails, too, the perilous one through Apache country to Sonora and the unknown way to California, leapt off from Zuñi. The best mission in the kingdom, Fray Silvestre Vélez de Escalante called this remote post. Still in his twenties, pious but level-headed, eager to win the Hopis or strike for California, the daring Vélez had joined Father Domínguez on his exhausting 1,700-mile exploration northwest from Santa Fe, through the Great Basin, south across the Colorado River, and back. Trail-weary and full of what they had seen, the explorers had returned to civilization at Zuñi on November 24, 1776, where Domínguez, the dutiful canonical visitor, after a rest, took the measure of this mission.

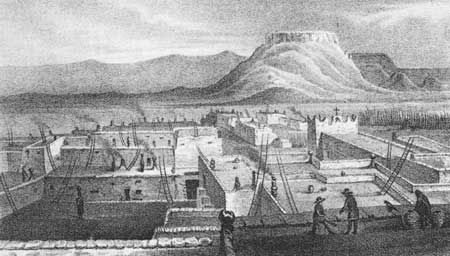

Here church and convento sat right in the middle of the pueblo. Facing east-northeast, the mission was surrounded on all sides by multi-level earth-and-stone house blocks. From a distance Zuñi looked more heaped up than it really was. Many of the houses rose on top of the crumbled ruins of their predecessors. In the seventeenth century and before, this had been Halona, one of a half dozen Zuñi pueblos nominated by Fray Marcos de Niza and cursed by Coronado as the Seven Cities of Cibola. It had been abandoned in the Revolt of 1680 and resettled in 1699 as the one and only Zuñi pueblo. Fray Juan de Garaycoechea, who ministered here from 1699 to 1706, probably used what he could of the pre-1680 fabric in constructing the renewed mission of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe. The water supply, Father Domínguez learned, was also a problem at Zuñi. The people could not depend on irrigation. They watered their distinctive little stone-walled garden plots by hand. When the unreliable wash dignified as the Zuñi River did not run, they dug wells in the sand, "some of which have good water and others, bad. In this way I indicate the great labor necessary for the building of church and convent, for, water being scarce, the difficulties may be imagined." [1] A century after Domínguez, ethnologist Victor Mindeleff noted a fact about Zuñi building that may have been related to the scarcity of water—Zuñi was "essentially a stone village." Adobes demanded more water and more work. Stones set in mud mortar (often concealed beneath mud plaster) made up most of the walls of the pueblo. The church, observed Mindeleff, was the notable exception.

Inside, the Zuñi church was dank and earth floored. Once his eyes adjusted, Domínguez could see by the light of the clerestory "a small new altar screen, as seemly as this poor land has to offer." His trail companion, young Vélez de Escalante, along with the Indians, had paid for it. Well-carved wooden images of archangels Michael and Gabriel flanked the canvas of Our Lady of Guadalupe. More than a hundred years later, in 1883, a self-righteous Adolph Bandelier would condemn as an act of plunder the removal of these and other religious artifacts from the Zuñi church by collectors from the Smithsonian Institution. Plunder or not, the act resulted from the almost unrelieved neglect that settled over the distant mission in the generation after Domínguez and Vélez de Escalante. [3] First, however, there was a rebuilding. It occurred, according to Custos Pereyro, in 1780. The facade as described by Domínguez, flat with door, balcony, window from the choir loft, balcony roof, and arched bell gable, all centered, gave way to one with hulking twin towers and deeply recessed front wall. An ample new balcony and high roof bridged the space between. Adobe belfries, poorly engineered, topped the towers. [4] During the nineteenth century, isolated Zuñi rarely saw a priest. None had lived here for seven years, carped Visitor Juan Bautista Guevara in 1818. As a result this mission had sunk to "the most deplorable state, totally heathenized, its inhabitants rooted in apostasy and polygamy while many of their children go unbaptized." Because of its remoteness and the large number of unconverted Zuñi Indians, alleged Guevara, the Franciscans "look upon that place either as a novitiate for those newly arrived in this province on as a kind of exile for the old ones." At that time, he claimed, the missionary from Laguna visited the Zuñis only two or three times a year, if they were lucky. [5]

From the Christian point of view, the situation did not improve. For a while the Zuñis themselves saw to the maintenance of the church. Artist R. H. Kern, looking down on the structure from a housetop in 1849, portrayed the roof in good condition. The twin towers no longer supported belfries, only the four telltale peaks at the corners, but there was already a sturdy bell gable surmounted by a cross. Lieutenant James H. Simpson, a member of the same party, reckoned the exterior dimensions of the continuous-nave building at about 27 by 120 feet. Inside, in his words, "a miserable painting of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, and a couple of statues, garnish the walls back of the chancel. The walls elsewhere are perfectly bare." [6] Thirty years later, in September 1879, as the pueblo celebrated a harvest ceremonial, the day of the ethnologist dawned at Zuñi. At first hardly anyone saw the approach of a skinny, twenty-two-year-old Anglo from Pennsylvania astride a government mule. He was Frank Hamilton Cushing, of the Smithsonian Institution, harbinger of "Colonel" James Stevenson's "collecting party." Told in Washington that he would be away probably three months, Cushing lived at Zuñi for four years, earned adoption by the people, mastered "their strange, clicky language," studied their ways, and later, much to the disappointment of his hosts, shared their secrets with the academic world. Colonel Stevenson wasted no time. Setting himself up a trading operation in two rooms at the rear of the Presbyterian mission, he began collecting in earnest, "and day after day, assisted by his enthusiastic wife [Matilda Coxe Stevenson], gathered in treasures, ancient and modern, of Indian art and industry." Some specimens, seemingly abandoned, especially those related to the Zuñis' defunct Roman Catholicism, they allegedly took. That, Cushing found out later, they should not have done. Even though the cemetery in front of the old adobe church appeared utterly forsaken, the entire ground to the Zuñi people was "a fetich whereby to invoke the souls of the ancestors, the potency of which would be destroyed if disturbed; hence the place is neither cared for nor abandoned, though recognized even by themselves as a 'direful place in daylight.'" Just because the church was toppling to ruin and harbored "only burros and shivering dogs on cold winter nights," that, Cushing learned, should not have been interpreted by outsiders as an invitation to help themselves.

Cushing promised that he would either get back the relics taken from them or he would bring them new santos although as it worked out he did neither. At the same time he tried to persuade the Zuñis to join him "in cleaning out the old church, repairing the rents in its walls and roof, and plastering once more its rain-streaked interior." But here they balked. Admitting that he "talked well" and that "the missa house" was indeed the sacred place of their fathers, they would not accept his logic. They did not want the church restored. "May the fathers be made to live again by the adding of meat to their bones?" they asked. "How, then, may the missa-house be made alive again by the adding of mud to its walls?" Later when a fierce storm in the night opened great seams in the old building's north wall, Cushing urged the Zuñis to tear it down before it fell on the women and children who passed by. Again his talk was good, but they refused to act. The fathers would no longer know their sacred place. "It was well," they told him, "that the wind and rain wore it away, as time wasted away their fathers' bones." [8] Fellow ethnologist John Gregory Bourke noted the effect in May of 1881.

For most of the nineteenth century, once a year, or once every two or three years, a priest would show up at Zuñi. He would say Mass—in the sacristan's house after the church became unsafe—baptize, and preach through an interpreter. In 1906 the Franciscan Fathers at St. Michaels, Arizona, took on the responsibility. Father Anselm Weber found the people of Zuñi well enough disposed to welcome the friars back "till an ethnologist [Matilda Coxe Stevenson], who had spent years at Zuñi in studying and committing to writing their mythology, their ceremonies, dances and customs, sent emissaries to the council to warn them not to allow us to establish a Mission among them. If they did, said the lady, they would find their customs and their ceremonials under attack. They would have to pay for burials and baptisms, not to mention first fruits and the tithe. If they missed Mass they would be whipped. "Whenever Catholic priests were among the Indians, there was trouble, as she knew from her own experience." Father Weber, in fact, managed to get her recalled by the Smithsonian. [10]

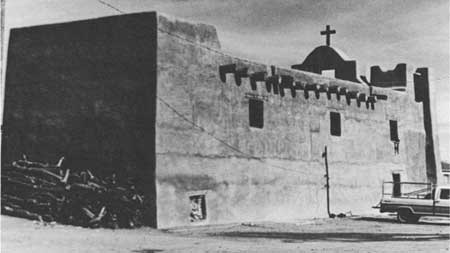

After that, the Franciscans moved very slowly toward a goal expressed by Weber in 1916—"the restoration and repair of the church." It took fifty years. Final negotiations between the Pueblo of Zuñi, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Gallup, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the National Park Service came about in the summer of 1966. The Pueblo leased the mission site to the Diocese for the purpose of "restoration, modernization, maintenance and operation of the Old Mission Church." The Diocese funneled money through the Pueblo to the Bureau which in turn reimbursed the Park Service for "archeological, historical and architectural services." To get round the ticklish legal question of separation of church and state, Federal participation was justified "for the reason that the restoration and reconstruction of the Old Mission Church will considerably benefit the Pueblo of Zuñi as a recreational and tourism development project." [11]

Excavation of church and convento ruins in 1966 and 1967 revealed some relatively late and drastic rebuilding. Tree-ring dates from the seven vigas still spanning the hollow shell confirmed the recollection of an old Zuñi man: the church had been reroofed last about 1905. Most of the north wall, in such bad shape in the 1880s, had fallen and been rebuilt 10 feet closer to the south wall. The length of the building had been reduced by more than 20 feet when a new sanctuary went up in front of the old fallen one. In terms of floor space, the overall loss was 1,000 square feet, down from about 2,800 to 1,800. Just who initiated all this work to rescue the Zuñi church around the turn of the century, and why, no one seems to know. [12] The handsome reconstruction of 1969, greatly aided by a hydraulic press that spit out ready-to-use adobes at the rate of four a minute, occupies the reduced floor plan. Inside, in a mural procession high up along the nave walls Zuñi artist Alex Seowtewa has painted colorful life-sized ceremonial figures. With the encouragement of the friars he has brought the Zuñi council of the gods right into the new church. [13] Frank Cushing would have smiled.

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||