|

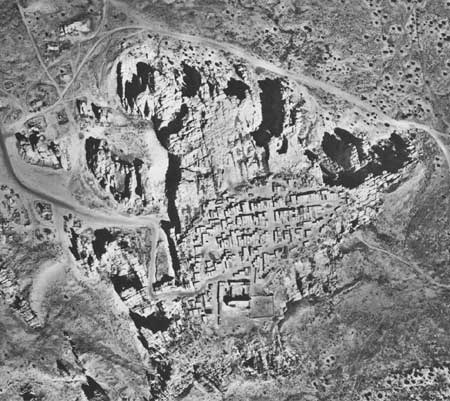

Ácoma Even after the dizzy canyon of the Colorado, which he had climbed down into just weeks before, Father Domínguez did not wish to go too near the edge at Ácoma, too near "such horrible precipices that it is not possible to look over them for fear of the steep drop." In places it was over three hundred feet straight down. "Although I have not spent so much time at the beginning of my description of other missions as I have here, it is because there is no comparison with the situation here. The little I have said to begin with at those places indicates in brief to the judicious reader the nature of the buildings and transportation in relation to the nearby rivers and easy transportation of all necessities. The contrary is true here, for there is not even a brook, earth to make adobes, or a good cart road. . . . This makes what the Indians have built here of adobes with perfection, strength, and grandeur, at the expense of their own backs, worthy of admiration." [1] Like some giant weathered altar of sandstone set out in a broad valley, the stately monolith of Ácoma held up an offering, an entire pueblo. It was "the most beautiful pueblo of the whole kingdom," exulted Bishop Tamarón in 1760, "with its system of streets and [three long parallel apartment buildings of] substantial stone [and adobe] houses more than a story high." To Charles F. Lummis, who popularized the slogan "See America First," here was "the most wonderful aboriginal city on earth, cliff built, cloud swept, matchless Ácoma." [2]

It is not surprising that reconqueror Diego de Vargas had found the massive church of Ácoma almost intact when he climbed to the top of the rock in 1692.

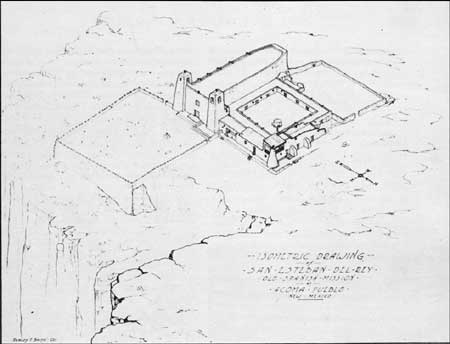

Construction of this church, "hardly less wonderful," in Lummis's words, "than the pyramids of Egypt as a monument of patient toil," had occurred between the year 1629, when Fray Juan Ramírez took up his lonely labor on the rock, and about 1641, when Ácoma was said to possess a most handsome church. Fray Lucas Maldonado Olasqueaín, whom the Ácomas killed in 1680, had written eight years before his death that church, convento, sacristy, and cemetery were among "the best there are in this kingdom." Merely leveling the building site had demanded enormous quantities of fill. The spacious mission complex, laid up initially of adobes and repaired time and again with field stone, rose near the brink, facing the rising sun. The church, whose shape resembled a huge coffin 45 by 145 feet on the outside, contained on the inside a single nave and sanctuary of about 3,600 square feet. Flanking towers added another 25 or 30 feet to the facade. Against the building's north wall sat the convento, a roughly 110-foot square of rooms and cloister around an interior patio-garden. Beyond it, a couple of hundred feet, stood the closest of the house blocks. [4]

Because there was virtually no earth, loose stone, or wood on top, everything had to be hauled up treacherous footpaths from pockets in the rock or from the valley floor below. Much of the pueblo itself, destroyed after the brutal battle with Oñate's Spaniards in 1599, was also rebuilt of adobes during the ministry of Juan Ramírez. If an Indian carried one cubic foot of dirt and stone in a leather bag on his back, the massing of the church walls and towers alone would have required 90,000 trips!

But that was not the half of it. To L. Bradford Prince the cemetery was an even greater miracle.

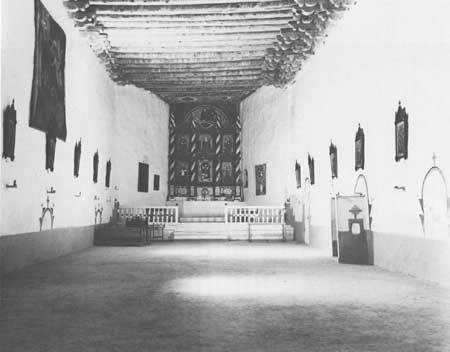

The Keres people of Ácoma have always felt that what they built on their rock belonged to them. The European presence, centered in Santa Fe over a hundred miles away and represented only intermittently by a priest, a lieutenant alcalde mayor, or a government school teacher, has not dissuaded them. In 1680, when other Pueblos brought down their churches, the Ácomas did not. They killed Father Maldonado, and later offered shelter to Pueblo refugees, but they refused to destroy what they considered their own. As a result, the mission church of San Esteban at Ácoma today would appear to contain more of the original seventeenth-century fabric than any other in the United States. [6] Although the ample baptistery, entered through a door to the left under the choir loft, crumbled in time and the doorway was walled up, the cavernous body of the church has changed little. The rough interior measurements by Domínguez in 1776 were confirmed by the precise measured drawings of the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1934, except for the height of the walls. The clerestory, which Vargas said had been broken out, was gone in 1776, and the roof was flat. Domínguez estimated inside wall height at 14 varas, on about 38-1/2 feet. The HABS drawings made it less than 30 feet. Either the friar, looking up at such a vast vacant expanse, overestimated, or, less likely, the walls were lowered during a subsequent roofing. "I don't see how this village could be taken by direct assault today," marveled Lieutenant Bourke in 1881, "even with improved arms. Horatius at the bridge said 'in yon strait pass a thousand may well be stopped by three'—but, were he to defend Ácoma, he could well with stand 10,000." Bourke saw the church to be "of massive proportions, but without symmetry or beauty." Much dilapidated "exteriorly," it was in good repair inside. A priest held services here once a month.

The exterior continued to slough off. In 1890, census taker Julian Scott, who described the impressive Ácoma convento in considerable detail, commented that the south wall of the church "is wasting away, as are also its huge towers, once square, which rise just high enough above the roof to admit of belfries." Upkeep of the hulking structure was becoming increasingly burdensome. Fewer and fewer Ácomas made their homes on the rock. They lived some miles to the north at McCarty's or Acomita along the valley of the Río San José near their fields. Perhaps not many knew that their church had been chosen as the model for the New Mexico building at the 1915 Panama-California Exposition in San Diego. Around 1902 some effort had been made to check the erosion of the mission. The two belfries were rebuilt crudely in square block form "of a conglomeration of adobe mud, adobes and rock cast together without respect to system except that it had a rock veneer." [8] With the willing consent of the Ácoma people, the encouragement of Father Fridolin Schuster, and the field supervision of L. A. Riley II, the Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of the New Mexican Mission Churches in 1924 commenced work on its biggest challenge. As at Zia, the Committee provided plans, a supervisor, tools, and materials; the Indians their labor. The first priority was a new roof on top of "boards and vigas that were already in place." Despite an improved path up the rock, the logistics of the job had Riley counting bags of cement in his sleep.

In six weeks it was done, and "strong enough," said architect John Gaw Meem, "to permit the Indians of Ácoma to walk over the roof as is their custom." During 1926 and 1927, with B. A. Reuter in command, the vast exterior of the building was gone over. The south wall, deeply eroded by the lashing of storms and by the action of water pouring out the canales and being driven back against it by wind, required tons of split rock and mud mortar to fill all the pockets and holes. Reuter added 5 feet to the length of the canales. Ácoma crews rebuilt the old terraces around the coffin-shaped back end of the building. After further repairs the walls were plastered with mud—first a rough coat thrown on by hand, next a straw-filled scratch coat, also thrown on "with just the necessary impact to imbed it well in all the variations of the preceding coat," and last a thin finish coat applied with trowels. Both towers, particularly the south one, had to be partially rebuilt from foundations up. By accident, workers came upon a cylindrical chamber in the south tower. Mined inside for valuable dirt to make adobes it was found to contain a circular wooden staircase. This Reuter restored, along with the doorway that once upon a time led out on the roof of the old baptistery but now led to a wooden ladder or a 20-foot drop. The sudden collapse of a portion of the front wall between the doorway and the north tower caught everyone by surprise. It was built back up. Finally, after the ugly boxlike belfries had been demolished with crowbar and pick, structures more in keeping with the "ancient model rose in their place.

"If it is so difficult," wrote a philosophical Reuter to the Committee, "to get the comparatively small job of restoration completed, it appears to me that it is only more worthwhile to completely restore this remarkable building whose gigantic proportions must have cost a previous generation the best efforts of their existence." [10] On and off, the efforts have continued down to the present. Though expedient, these have not always been the best. As at Laguna, the Ácoma church had an elaborate altar screen and canopy painted by the Laguna santero, the gift of Alcalde mayor José Manuel Aragón in 1802. Damaged by water and dirt from the leaking roof, screen and canopy have been "restored" more than once in the twentieth century. They are brighter today than ever. [11] Since 1970, when the United States government settled the land claim of the Pueblo de Ácoma for $6,107,157, the Ácoma people have looked to improvements that will renew the Sky City and attract tourists. They have devoted heroic efforts to preserving their singular church, convento, and cemetery, aided in this by matching federal funds for historic preservation. In 1974, to prevent collapse of the cemetery retaining wall and an avalanche of dirt and bones, they hauled hundreds of tons of split sandstone to the top of the rock—in trucks now, up a steep paved road—reinforcing and facing it with stone and cement masonry.

The plan is to encase the church in a similar jacket, at least the more exposed parts of it. This masonry, two and three feet thick at the base and tapering inward as it rises, already covers the apse and about a third of the south wall. At present the scaffolding has been removed and the work stopped, pending further federal monies. Meanwhile, in the convento in 1975, the Ácomas and archaeologist Michael P. Marshall, who came as a condition of the matching funds, made some interesting discoveries. Cleaning out the recent trash and blow sand that had piled up in the patio and digging several test trenches, they found beneath the four facing walls waist-deep stone foundations set on bedrock. To create the mission garden this giant "planter" had been filled with "organic" soil from the pueblo's ancient oven-the-edge middens, soil that contained varieties of scrambled prehistoric pot sherds and human burials, Here, in mid-December 1776, Father Domínguez noted peach trees, and, in a corner, the latrine, or, as he so felicitously put it, "a small recess for certain necessary business." As part of the work in 1975, the Ácomas reroofed the enclosed four-sided convento cloisster, which must have been in its heyday a riot of colors. Old square-hewn vigas and peeled latillas still bore traces of red, black, and yellow pigments. Beneath the whitewash, hints of wall decoration showed through—animals and flowers and rainbows. Along the length of one entire wall a procession of horsemen once paraded. Painstakingly, archaeologist Marshall scraped off enough of the overlay to reveal bright geometrical patterns, a skillfully drawn antelope, and the first of the riders, evidently a priest. Today there is talk of restoring this remarkable mission art gallery. [12]

If Father Domínguez were resurrected for a visit to Ácoma in the 1970s, he would praise the road to the top and he would shudder at the thought of using one of the outhouses that perch in the rocks near the edge. But the church, more than any other in New Mexico, he would recognize. It has no electric lights and, as yet, no heaters. The floor, except for the sanctuary, is dried mud. And the walls, freshly whitewashed every year before the feast day, still look taller than they actually are. [13] As it sits today, partially stone-faced, the temple of San Esteban de Ácoma calls to mind as never before the antecedent fortress-churches of central Mexico. Such improvements, what ever their impact on "the ancient model, serve to remind the visitor of a fact he should not forget. Roman Catholic church or not, National Historic Landmark or not, this building belongs to the Ácomas. Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||||