|

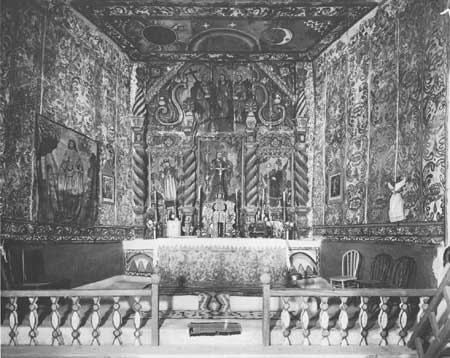

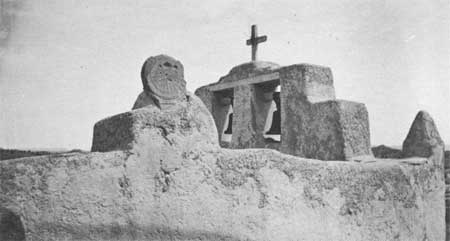

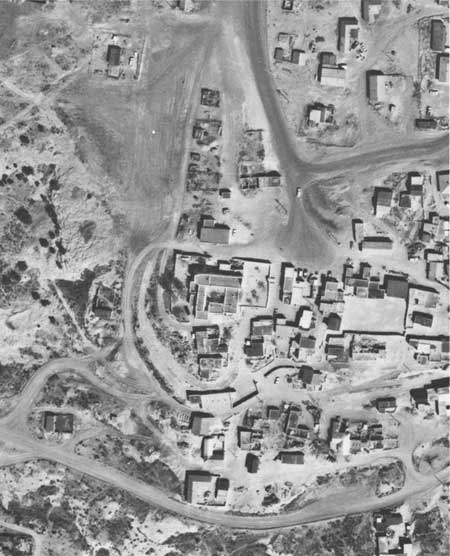

Laguna In size, appearance, and natural setting the picturesque and historic mission of San José de la Laguna has always suffered by comparison with the more monumental and historic mission of San Esteban de Ácoma, its neighbor. Lieutenant John Gregory Bourke set down a common reaction, one he shared with Bishop Tamarón, Father Domínguez, and a host of travelers before and after, when he wrote this entry in his journal for Sunday, October 30, 1881. "The church (San José de Laguna), once the seat of a convent and surrounded by monastic buildings now in the last stages of ruin, is itself in fair preservation. To the observer just from Ácoma, it appears small and petty in contrast with the noble edifice dedicated to San José [San Esteban] at that point: but its actual dimensions are respectable. Its facade (100' long) is 30 ft. wide by 45' high to the foot of the cross. . . . Seen from the windows of the cars of the Atlantic and Pacific Rail Road whose track runs within 50 yards of the noble old wreck, the white-washed walls suggest the idea of a beacon planted in the midst of a restless ocean of strife and angry passion. The interior walls are whitewashed with a band of pattern running around the nave, in red and yellow with black border. The scarcely concealed symbolism of this ornamentation will be apparent to any one who will take the trouble to compare it with examples obtained from Zuñi and other avowedly heathen pueblos. We can discern clouds, snakes and the walls of Troy, all peculiar to the hieratic symbolism of the Estufas [kivas] or of the Sacred ceremonies of any kind." [1] The pueblo of Laguna had grown out of a gathering of refugees, mostly Keresan speaking, who for one reason or another did not choose to return to their homes after the reconquest by Vargas. They came together, or, as the Franciscans told it, they were collected like wandering sheep by the apostolic shepherd Fray Antonio Miranda, on a hill by a lake 45 miles west of Albuquerque. Founded formally in 1699, seven years before Albuquerque, Laguna by 1706 had a reported population of 330 souls and a church "being built." That same church, laid up of field stone from the hill and mud, has endured, much and oft-repaired, down to the present. [2] "Very gloomy" were the words Domínguez chose to describe the interior of this single-nave structure in 1776. He should have come back thirty years later. Sometime between 1800 and 1808, an itinerant folk artist created an altar screen and painted the sanctuary with colors and patterns and pictures that made it sing. Not even his name has survived. He is known simply as the Laguna santero, for here he achieved "the finest flowering of the New Mexican santero style." His patron was José Manuel Aragón, alcalde mayor of the western pueblos from the mid-1790s until 1813, who lived with his family at Laguna. Aragoón's name is inscribed high up on the back of the screen. A contemporary, Fray José Pedro Rubí de Celis, inventoried this singular pious work in 1810.

Standing in the Laguna church today one can follow precisely what the friar was describing in 1810, all but the "curtains" painted on the walls, "strongly brushed in subtle shades of gray, black, greenish gray and ochre yellow." These, unfortunately, were covered with whitewash in 1968 in the wake of a lightning strike and a shoddy reroofing job over the sanctuary. But the altar screen, "by far the most beautiful and best preserved" in New Mexico, thanks to the concern of Father Agnellus Lammert and a thorough conservation by E. Boyd in 1950, has defied its age. [4] Certainly one of the most pleasantly surprised visitors to enter the Laguna church was Dr. P. G. S. Ten Broeck, assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army, who did so after breakfast on Christmas Day in 1851.

Since the days of the Spanish alcaldes mayores, outsiders who have lived among the people of Laguna have proved more often a curse than a blessing. Baptist and Presbyterian missionaries, as well as other Americans who moved in and married Laguna women, had precipitated a major split in the pueblo by the late 1870s. Kwime (Luis Sarracino), a forceful leader who had converted to Protestantism, was threatening to tear down the Roman Catholic church, which evidently had been closed for a time. Hamí, sacristan of the church and a leader of the opposition, resolved to defend the historic structure.

With its repair Hamí's descendants have had help, sometimes more than they have wished, Father Fridolin Schuster, the Franciscan from Gallup who had charge of both Laguna and Ácoma, convinced them that the church did not need a board floor. Today the women of the pueblo still coat the packed earth floor with a mud wash containing straw, even in the sanctuary where Indian rugs are used instead of modern carpet or linoleum. In 1920 Schuster sought the advice of the Museum of New Mexico and of architect A. C. Hendrickson about a tar and gravel roof. It was on by the summer of 1923, in time for the feast of San José, September 19. The nave ceiling thus protected is one of the most pleasing in New Mexico, of great round vigas and peeled-pole latillas, the latter tightly laid in herringbone pattern and accented in soft earth color. Between 1932 and 1936, as the Laguna people returned to Father Agnellus Lammert portions of the old convento which they had used variously as a meeting place, for storage, and as stables, he rebuilt, remodeled, and restored them for the priest's quarters. The superbly detailed measured drawings done of church and convento in 1934 by the Historic American Buildings Survey allowed Father Lammert to remodel the kitchen on its old foundations. [7]

Seen from the windows of an air-conditioned automobile on Interstate 40, the mission at Laguna still stands out like a beacon above a swollen sea of browns and tans. In 1977 the entire hilltop plant—church, convento, and rebuilt cemetery wall—was restuccoed white. Other plans for Laguna, containing elements of stabilization, restoration, and modernization have mission watchers biting their fingernails. Removal of the ugly garage alongside the north wall of the church will surely be an improvement. Likewise replacing the rudely built plywood roof over the sanctuary. High-intensity electric lighting and baseboard hot-water heating, say the architects, can be less obtrusive than naked light bulbs and space heaters. [8]

Most controversial, however, has been the suggestion by some Lagunas that the whitewash and mud plaster be stripped from the inside walls, destroying the bold native designs painted the length of the nave. Once hard plaster is applied, they vow, the pattern can be repainted. The interior will require less maintenance, less retouching in the old way—unless, warn the preservationists, the new plaster falls off. Even more sobering is the fact that hard plaster could cost the pueblo more than it is worth. Public monies needed for the church project will be made available only if the canons of historic preservation are observed. Economics, not tradition—or, better said, economics in support of tradition—appear to have decided the issue. The interior walls of the church of San José de Laguna, mud-plastered, whitewashed, and painted—a singular "cultural resource," in the words of the bureaucrats—will endure, at least for now.

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||