|

Jémez More than the forty-six wrought beams without corbels above the nave or the half-dozen purificators in the sacristy, what interested Father Domínguez at the pueblo and mission of San Diego de Jémez in 1776 was the rigid regime that Fray Joaquín de Jesús Ruiz had imposed upon its Towa-speaking natives. The resolute fifty-one-year-old Fray Joaquín marched the Jémez people around like a military drill instructor, so far as that was possible. So impressed was Domínguez that he ordered the missionary to write down exactly how the system worked, which Ruiz did under the headings Mass, Religious Instruction, Government of Choirboys and Little Sacristans, Kitchen, Wood for Winter, and Harvest. For Mass the bell was rung at sunrise.

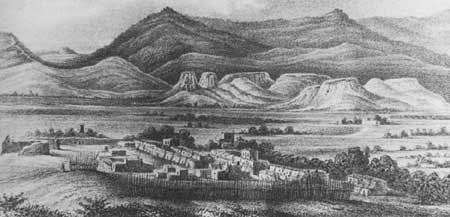

A century and a half before Ruiz and his rule, Fray Alonso de Benavides had characterized the Jémez nation as "one of the most indomitable and belligerent of this whole kingdom." Accused of trafficking with Navajos and clinging tenaciously to their old ways, these "mountain folk" had resisted the reduction of their several pueblos to one or two mission communities. Repeatedly they had dispersed. The formidable stone mission of San José de Giusewa, today a state monument near Jemez Springs, they had deserted by the late 1630s. They had martyred Franciscans in 1680 and 1696 and had scattered again. By 1706, however, three hundred of them were settled on the east bank of the Río Jémez at or near one of their earlier pueblos known as Walatowa, "and others keep coming down from the mountains where they are still in insurrection." By 1706, claimed Custos Juan Álvarez, they were building a church: hardly one worth mentioning, insisted a successor. If every custos had applied himself as diligently as Fray Francisco de Lepiane, according to Lepiane himself in 1728, the missions of New Mexico would have progressed more rapidly

Father Lepiane, back in Mexico City defending his administration, may have exaggerated, or perhaps the transept he said he built was closed up in subsequent remodeling. Or his church may have fallen. Whatever the case, Domínguez found no transept in 1776, just one very long continuous room, 46 varas from doorway to altar, with bare earth floor and "its interior not of the worst." Oriented toward the south, the church showed its back to the main cluster of house blocks, just as the present one does. Father Ruiz had built a new sacristy against the east wall and put the two-storied convento in order "by rebuilding the older structure." Thirty years later Fray Isidro Cadelo persuaded some of the local Spaniards to contribute produce toward purchase of a new altar screen. Still, when he handed the mission's inventory to Governor Joaquín del Real Alencaster in 1806, the friar appended a note "humbly imploring him please to bring to the attention of the King Our Lord the want of sacred appurtenances for divine services this mission suffers." [3] Although Father Domínguez made no mention of the fact, there were evidently two church sites at Jémez even in his day: one where the structure in use stood in 1776—and where the nineteenth-century replacement stands today—due south of the pueblo, and the other 150 yards or so west of that structure in a pronounced bow of the acequia, where the ruins of Lepiane's church, or an earlier one, slowly weathered away. In 1833, when Rafael García and the Jémez Indians were disputing a remeasurement of the pueblo's "grant" of one league (5,000 varas) in each of the cardinal directions, the two church sites became an issue. Traditionally such measurements were begun from the church door from the cross in the cemetery. García, evidently one of the pueblo's neighbors on the west, wanted to begin from the church in use, which would have given him an advantage of 150 yards or so. The Indians, who had been here longer, wanted to begin "from the first church which was farther down [west] than the present one because it was expedient to move it." Thoroughly confused, the local alcalde wrote to Santa Fe. Which church site was he to choose, or should he split the difference and begin halfway between? The answer was curt. He should consult a lawyer. [4]

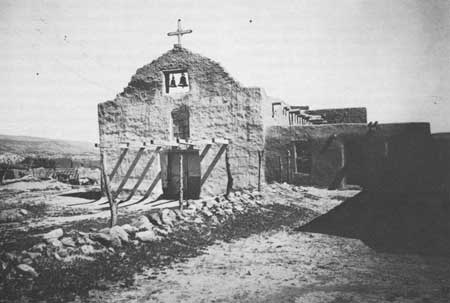

On the way to reconnoiter the Navajo country in 1849, Lieutenant James H. Simpson set down his impressions of the church at Jémez pueblo, by that year in a decrepit state.

When Lieutenant Bourke and his companions halted their ambulance near the old Jémez church on November 5, 1881, they could see that its roof had fallen. Facade and bell gable still stood like a false front on a movie set. Bourke made a sketch, but admitted that

That, for all practical purposes, was the end of the "Domínguez church." Returning with Judge Prince from Jemez Springs in 1885, C. B. Hayward noticed that the church at the pueblo of Jémez "has tumbled down. Through the energy of Padre — [J. B. Mariller, who served Jémez between 1881 and 1894] a new one is now in process of construction." Completed in 1887 or 1888, this building rose almost on top of its fallen predecessor. It was lower and shorter featuring transept and clerestory, in sum, a flat-roofed adobe traditional. Except for the rude planked balcony that rested on seven choir loft vigas poking through the wall, the simple facade looked just like the previous one, even to stepped bell gable and the same two bells. [7]

A renewed Franciscan ministry began at Jémez in 1902 when Archbishop Bourgade called from the Cincinnati province friars with German names. If it lacked the stern regimentation of Father Ruiz's tenure, it nevertheless prospered. From the leaky convento attached to Father Mariller's church, where "the Brother had to wear raincoat and rubbers while preparing the meals," the brown robes moved to a fifteen-acre enclave some five hundred yards west. There they established headquarters for a sprawling parish of more than 3,000 square miles and thirteen mission stations. There, too, as part of a complex that included a large residence for the friars, a school, and a convent for the Franciscan sisters who came to teach, Father Barnabas Meyer blessed a new chapel on the feast of San Diego in November 1919. More or less neo-Gothic, it burned in 1937 and was replaced the following year by a handsome New Mexico mission-style building displaying the best of Jémez carpentry. [8] The pueblo church, meanwhile, the one erected under the tolerant eye of Father Mariller, had taken on a plain and modern look by the early 1920s. With pitched tin roof and gray stucco exterior it serves today as successor to the one Father Ruiz marched the Jémez people in and out of two centuries ago because, as Domínguez put it, "a certain rebelliousness demands great firmness." [9] Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||