|

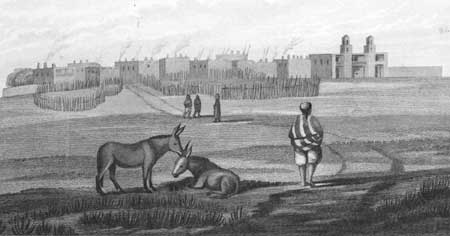

Santa Ana Father Domínguez would have appreciated the bumper sticker PRAY FOR ME, I DRIVE NM 44. If the menace in his day was attack by an enemy war party, not a loaded, forty-ton dry-cement truck, the impact could be equally fatal. From San Felipe the road south kept to the river. Where the Río de Jémez flowed in from the west, the traveler bound for the Keres pueblo of Santa Ana turned and followed this broad but scanty stream "of very bad water and bottom" through sandy unfertile-looking hills. For 7 miles, with Santa Ana Mesa always on the right, he paralleled New Mexico 44. Another more direct route, of steep ascent and descent, led straight across the top of the mesa. Up there Diego de Vargas had found the people of Santa Ana in 1693. He had induced them to come down and build "on a little plain that hangs from the Skirt of the said mesa." It proved a poor choice. [1] Passing through Santa Ana in August 1696, Vargas noted that Father Custos Francisco de Vargas, no relative and no friend, had a convento already up. Timbers and stacks of adobes were at hand for construction of the church. The Franciscan "had brought the carpenters of the pueblo of Pecos to hasten working these timbers and likewise the doors, which he specified and the carpenters took the measurements in order to make." Evidently meant to serve the more than three hundred residents of Santa Ana only temporarily, the new church was small, "four varas wide by seventeen long, with pine timbers." Still, it had sacristy, antesacristy, baptistery, and a little adobe-walled cemetery. [2] Thanks to some detailed entries in the inventory book, by which outgoing ministers turned over accountability to their successors, an uncommon record of common mission building has survived for Santa Ana. A new convento, which incorporated the first one as its kitchen and storeroom, was finished by 1717, the work of young Fray Pedro Montaño. It featured "eight cells and inner cells, kitchen and storeroom, and cloister with two wooden doors." Some years later Fray Diego Arias de Espinosa, who initiated another major phase of construction in the early 1730s, had much to inventory.

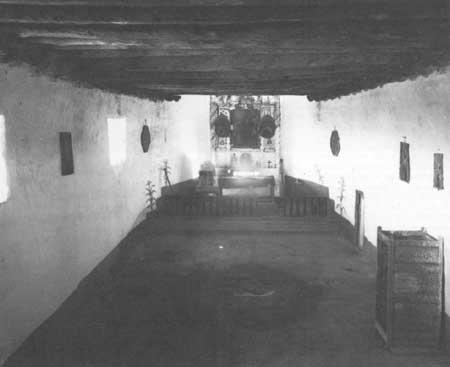

Before the year was out Alcalde mayor José González Bas had borrowed eighteen of the vigas, possibly for the chapel he and his brother were building at Alameda. The work at Santa Ana, meantime, stopped dead. For nearly sixteen years the partly laid-up walls of the new church just stood there. Not until the arrival of energetic and outspoken Fray Juan Sanz de Lezaun in the summer of 1750 was work resumed, and then with a vengeance. Sanz mobilized the entire pueblo, sending men and oxen to cut and haul down vigas setting others to making and laying adobes, while he supervised, urged, and sweated alongside them. In just under two and a half months, without the least help from Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín or his appointees, Santa Ana's new church stood complete "in every detail." That, wrote Sanz and his co-worker at Zia in passionate defense of their ministry, was the sort of dedication that had long sustained the Kingdom of New Mexico. [4] Boasting aside, Santa Ana now had a suitable church. It faced east with the pueblo, of more or less parallel house blocks, behind and to the south between it and the broad thirsty riverbed. Sanz de Lezaun's successor described the entire physical plant room-by-room, door-by-door, down to privies and the kitchen drain. The facade of the church and the placement of the convento were unique in all the colony. "This church has a mirador to the south [above the baptistery]. The principal front, featuring a balcony, is sixteen varas across [twice the width of the nave inside] with its wooden railing and three main buttresses that support it." That made the facade look unusually broad, including as it did the baptistery on the south and a covered passageway from convento to sacristy on the north. Straight-on, it exhibited six bays, three below at ground level with entranceway through the wider middle one, and three above at balcony level. The convento, a full square of rooms with cloisters on all four sides around the patio within, lay off the northeast corner of the church connected to it by only the passageway. [5] Judging from his comments in 1776, Domínguez rather liked the arrangement.

Probably not long after the turn of the nineteenth century, some admirer or colleague of the Laguna santero, not as skilled as the master, executed a main altar screen for the church of Santa Ana, just as he had at San Felipe. Here, instead of a statue, he had a large oil painting of St. Anne around which to construct the reredos. Considered old by Domínguez in 1776, this canvas is still in place as the centerpiece, still lighted by the clerestory overhead. Whatever, if anything, of his own design the Santa Ana santero put on the side panels is gone. The two oval paintings hanging there now on "flimsy boards painted white" barely fit. The only things he would recognize today, mentally applying gallons of paint remover, are his "sun burst" at the top and his heavy twisted pillars, colored green and white like candy canes. Outside, an arched bell gable centered over the main doors gave way to two tower belfries. In Domínguez's day there had been no bell and, in his words, "necessary summonses are sounded by a war drum." Father Pereyro in 1808 considered the entire structure "decent and adorned." Bishop Lamy called it well preserved in 1874, but Lieutenant Bourke, seven years later, saw cracks.

From Domínguez to Bourke, for more than a century, visitors to Santa Ana had noted the ill-suited location of the pueblo. There simply was not enough irrigable land nearby. Floods washed away the fields they planted out in the riverbed, and the other lands were uneven and impossible to irrigate. Of necessity the Santa Anas began buying farmland on the Rio Grande even before the middle of the eighteenth century. At first they moved to these Ranchos de Santa Ana seasonally and later they lived there year-round. Gradually this migration relegated the pueblo proper to its present role as a ceremonial site. An agreement in 1903 between the principal men of Santa Ana and Archbishop Peter Bourgade reflected the shift in settlement. The Indians bound themselves to put up and to maintain a building at Ranchos or Ranchitos, for use as a chapel and school. Even though the old pueblo church would "continue to be the principal chapel," the archbishop would not be obliged to have a priest celebrate Mass at both places when the people were at Ranchos. [7]

Around 1916 the roof of the old church was leaking all over the place. On their own, the Santa Anas decided to reroof. Far up in the Jémez Mountains they cut the pines for vigas and they bought from a sawmill green rough lumber for ceiling slabs. Directly on top they piled a foot of dirt. By the mid-1920s the roof was leaking again. Thus in 1927, when the Committee for the Preservation and Restoration of the New Mexican Mission Churches volunteered to pay for a new and better one, the Indians consented. Construction boss B. A. Reuter explained the advantage of latillas, the little peeled poles that they had replaced with lumber. Because the former were round and covered over by a layer of "the indestructible leaves of yucca or some hard stemmed slough grass" before the dirt was applied, they could breathe and dry out. Dirt piled directly on lumber, however, got wet, trapped the moisture, and as a consequence the boards rotted. After he had convinced them, Reuter then had to turn around and tell the Indians that it was too late in the fall for them to go out and cut latillas. With the modern roofing he intended to apply, lumber would do admirably well.

Cost to the Committee totaled $1,399.62. The people of Santa Ana, who had supplied all the labor and earned the respect of Reuter, were grateful. "They also insisted that they were not sentimental about the little fifty cent towers, that they, if they saw fit, could go up there next spring and completely restore them in one day. At least now the roof did not leak. [8] Today the driver who dares take his eyes off New Mexico 44 for a look across the wide alkaline bed of the Jémez River can still make out the low stone and earth houses of Santa Ana pueblo. Just above them in silhouette rises the church, if not the roof, that Father Sanz de Lezaun laid up in 1750 in record time.

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||