|

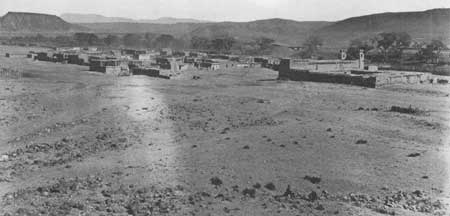

San Felipe "Like something tucked in a corner," the Keres pueblo of San Felipe since about 1700 has occupied a flat wedge-shaped piece of ground confined on the east by the Rio Grande and on the west by dark and vast lava-strewn Santa Ana Mesa. Previously the people of San Felipe, who sided with reconqueror Diego de Vargas, had built a defensive pueblo on the very brow of the mesa. There they would be secure from their neighbors who chose to fight on. Once the Spaniards had quelled the revolt of 1696, it was safe to come down. Thus a new church and pueblo, reported Fray Juan Álvarez in January 1706, "are being built, the latter having been moved down from a high mesa." [1] The church on the valley floor 35 miles southwest of Santa Fe was judged inadequate by Fray Andrés Zevallos, minister at the pueblo from 1732 to 1741. So he rebuilt in 1736. Preoccupied with the church, Zevallos paid little heed to the convento. When the veteran Fray Pedro Montaño moved in late in the summer of 1743, he could hardly believe it.

From the sound of it, the San Felipe church in 1776 looked much as it does today. Less than a hundred yards south of the pueblo's main plaza and facing east on the river, it still features two buttress-bell towers flanking the doorway with a roofed balcony between them. Neither the continuous-nave plan nor the dimensions have changed much since then. Even the carved wooden statue of St. Philip the Apostle made by Bernardo de Miera y Pacheco, and sold to the pueblo at too high a price in the estimation of Domínguez, is still here, albeit much repainted. "And although it is not at all prepossessing," the Franciscan allowed, "it serves the purpose." [3] A major rebuilding of the 1736 structure, which did not greatly affect its appearance, occurred shortly after 1801, the year Fray José Pedro Rubí de Celis took over. "The church," Father Pereyro noted in 1808, "was rebuilt with its two new towers." That meant, at the least, a new roof and probably the two-tiered belfries sketched by Lieutenant Abert in 1846 and by Lieutenant Bourke in 1881. [4] Inside, Rubí had a new main altar fashioned, presumably with a wooden screen to fit the back wall of the sanctuary. This reredos, assuming that it is, under layer after layer of paint, the same one as today, featured pillars carved to look twisted. The latest thing in New Mexico church ornamentation at the turn of the nineteenth century, altar screens with twisted pillars must have appeared in numerous places. A few survive. At San Miguel in Santa Fe and at Zia, where they are dated 1798, and at Laguna and Ácoma, these screens have been attributed to a single artist, the now anonymous "Laguna santero." At San Felipe, however, and at neighboring Santa Ana, the twists are flatter, the capitals and finials cruder, plainly the work of less skilled hands. [5]

Lieutenant Pike, after crossing and noting carefully the ingenious eight-span wooden bridge over the river at San Felipe, met Father Rubí and found him a good host. A native of Puebla de los Ángeles in Mexico, Rubí was forty-two years old in 1807.

Although much of the convento that Father Montaño worked so hard to repair, where Father Rubí entertained Lieutenant Pike, has long since crumbled to dust, the people of San Felipe have kept their church in good repair. "It is cared for most faithfully," wrote Prince in 1915, "being whitened every year until it glistens in the bright sunlight." Actually only the facade between the towers was whitened, in the old days with gypsum wash and now with stucco. Here from time to time as at Santo Domingo and Cochití, artists of the pueblo have availed themselves of the exterior wall sheltered by roof and balcony. At present two spirited pinto horses, light colored with black manes and tails, face each other at balcony level. All the wood of the facade, from massive cross timber and corbels to balustrade and doors, has been freshly painted in four colors—a light brownish gold, an orange rust, black, and white. Many a tourist, alerted by the conductor, has snapped a photo of San Felipe across the river from a moving train. Others have got off, hired a conveyance, and attended the pueblo's famed Christmas Eve Mass. In 1912, on the afternoon of December 24, young Father Jerome Hesse, a Franciscan at Peña Blanca, set out for San Felipe astride his horse. It was long after dark when "the dull sound of the old cracked church bell" announced his arrival. He ate supper, administered Extreme Unction to a desperately ill woman with the aid of an interpreter, and warmed himself a few minutes by the fireplace in the sacristy. Then he retired to a small room in back for a little sleep.

Except for the tarpaper on the packed earth floor, the big gas heaters overhead, and the fluorescent light in the sanctuary, it is not so different today. Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||