|

Cochití With the Keresan-speaking pueblo and mission of San Buenaventura de Cochití, twenty-odd miles more west than south of Santa Fe, the overscrupulous Father Domínguez began his commentary on the Río Abajo missions west of the river. The church at Cochití, he reckoned, was just about the plainest New Mexico church imaginable, and "very gloomy" inside. The continuous nave had neither choir loft nor side altars. Its flat, unadorned facade looked eastward away from the house blocks. A small convento hugged its south wall. The three-sided cloister within was so dark it reminded him of a dungeon. [1] Either Domínguez could not find out anything about the building of this church or he did not bother. For a century before and a century after 1776 there is hardly a clue. Both tradition and potsherds hold that the Cochitís have occupied this site since before the coming of the Spaniards. The eighteenth-century church may embody the ruins of an earlier one. The friars in 1789 and 1796 who inventoried one large and one small bell "in the tower" seem to have used the word loosely as a synonym for the simple bell gable. They had built no towers. Father Pereyro in 1808 ignored the Cochití church. In 1819, however, the structure stood in urgent need of a "mason." Crusty, sixty-six-year-old Fray Francisco de Hozio, longtime presidial chaplain doubling in 1819 as Franciscan superior, was making his visitation. What he found at Cochití annoyed him so much that he sat down and wrote to the governor in Santa Fe.

Three days later Governor Melgares ordered the alcalde of Santa Cruz de la Cañada to send "the mason Madrid, under appropriate guard, to Cochití to build up the church, on the basis that he should have done it already." Melgares, in his reply to Father Hozio, used the verb componer, to repair, and in his order to the alcalde, levantar, to raise up or build. Whatever else had been done, the structure could not be roofed until Madrid finished laying the top courses of adobes. Perhaps at this time the sanctuary, as wide as the nave in Domínguez's day, was rebuilt in its later narrower form, the facade redone with open narthex and balcony, and the choir loft added. The alcalde was to notify his counterpart in the Cochití district to keep Madrid in custody until the job was finished. It would teach him a lesson, "that he should be more punctual when it comes to the house, the honor, or the worship of the One True God." [2] Fray Juan Caballero Toril, who lived at Santo Domingo and cared for Cochití as a visita, tried to teach the Cochitís a similar lesson late the same year. On November 19 he had caught them "with an altar of idols, worshiping them. I took them away and they were torn to pieces and burned in the middle of the plaza." Entering a note in the marriage book, Caballero warned his successors to be ever so vigilant. [3] One successor at least, the young Frenchman Noël Dumarest, would never have burned a Cochití "idol." He would have asked to borrow it so that he might make a sketch of it. Convinced that the ways of the American Indian were near extinction, Dumarest, an ethnologist at heart, wanted to preserve a record. He noted the customs of the Keres at Cochití and the interplay between Roman Catholic and Pueblo practices. To enforce Catholic marriage law, for example, the pueblo governor would send his assistants to the houses of young people suspected of premarital sexual intercourse. Either they "had to promise to get married or the young man had to mix mud and carry it to the woman for her to plaster the exterior of the church. All the pueblo knew what that meant." So, rather than face the ridicule of the whole pueblo, they usually promised. [4]

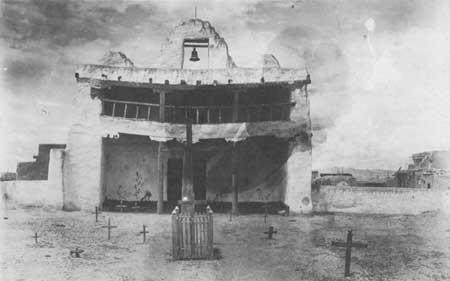

The roof of the mission church at Cochití, both outside and in, became an object of interest to late nineteenth-century visitors. In November of 1880 Adolph Bandelier and photographer George C. Bennett had climbed by ladder first onto the one-story convento remnant and then by a second ladder to the church roof with camera, tripod, and other necessary gear. While Bennett set up his equipment, Bandelier, always the scavenger, "gathered many specimens of pottery, recent—painted, glazed, and corrugated. Also lava and obsidian, moss agates, flint, etc., showing that the soil [covering the roof] was taken from the vicinity." The following year Lieutenant Bourke commented on what lay beneath the roof.

C. B. Hayward, publisher of the Santa Fé Daily New Mexican, dropped in at Cochití with the Hon. L. Bradford Prince en route to the Jémez hot springs in 1885. Hayward thought "the ceiling, covered with the efforts of some native artist with figures of animals (the horse predominating), looked very picturesque. In the language of a little Indian boy in looking at the ceiling, 'Mucho horse! mucho horse!!'" Prince did not much like the local art. What interested him were the aging oil paintings that together made up the altar screen, a large canvas of St. Bonaventure and six "scenes in the life of our Lord—the Nativity, the Transfiguration, the Last Supper, and three connected with the Crucifixion." The contrast between altar paintings and ceiling, from Prince's Episcopal point of view, was stark.

The Austrian Franciscans who assumed administration of Peña Blanca parish in 1900 felt very much as Prince did about Cochití ceiling art. But they went too far. They had no sympathy for these traditional adobe churches Prince loved so well. They changed the roof outside and in—the entire building in fact. Before their remodeling, to be sure, it stood in ill repair. Afterward it was unrecognizable. "The beautiful Cochití mission church" moaned Paul A. F. Walter in 1918, "has been unfortunately transformed into a nondescript chapel with huge tin roof and an arched portal, evidently an attempt to mimic the California mission style." Earle R. Forrest, who followed Prince closely in word and sentiment, abhorred this "only discordant note in an otherwise perfect Indian pueblo. The old flat roof and picturesque Franciscan belfry have been replaced by corrugated iron and a high pointed steeple. The balcony was removed from the outside and the entrance was inclosed by an adobe porch with three arches, the only attempt at adornment." Ironically, the heavy, 20-foot-tall steeple caught the wind and put such a strain on the walls beneath that they began to crack. To the secret delight of preservationists, it had to be cut down to a stubby box-like cupola. [7]

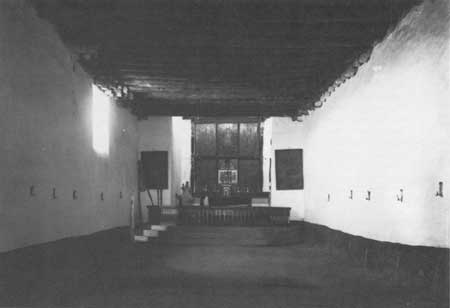

Late in the 1930s Fray Angelico Chavez, the first native-born New Mexican Franciscan, discussed with the leaders at Cochití a thorough restoration of their church. It could be made to look again as it did in the earliest photographs. The Indians agreed, but World War II intervened. Not until the mid-1960s were they prepared to act. Architect Robert Plettenberg, then of Santa Fe, supplied the drawings. All the families of the pueblo were assessed and the work began. Today Bourke or Bandelier—and perhaps even the delinquent mason Madrid—would again recognize the church at Cochití. [8]

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||