|

Tomé The fertile Rio Grande bottomlands at "lo de Tomé," Tomé's place, had belonged to the patriarch Tomé Domínguez de Mendoza who, "with swollen feet and knees and other ailments . . . among them gout and a stomach disorder," did not return after the Revolt of 1680, in which he claimed to have lost thirty-eight members of his family. In 1739 a group of land-poor Albuquerque settlers got together and petitioned for Tomé's abandoned place. Put in possession on July 30, they called their new community Nuestra Señora de la Concepción de Tomé Domínguez, alias lo de Tomé, or simply Tomé. [1] Eight long leagues south of the church at Albuquerque over a road made dangerous by marauding Navajos, Apaches, and Comanches, the people of Tomé took matters into their own hands. By 1742 they had built, not of adobe but of wood, a "rather decent" little temporary chapel. Then they tried to justify it. Tomé was more than a rancho, and therefore the bishop's recent decree forbidding the celebration of Mass at ranchos did not apply. They asked don Santiago Roybal, vicar of Santa Fe, for a license to construct a permanent chapel, "and in the meantime to be allowed the celebration in the one we have built of wood, enjoying thereby the benefit of a sick person receiving viaticum." [2] The vicar on October 24, 1742, forwarded their petition to Durango. The following July they assembled to hear read the reply of Bishop Martin de Elizacoechea. The prelate had bestowed on them his license for erecting a chapel. And he had empowered Vicar Roybal, once the building was up, judged decent, and provided with the necessary appurtenances, to bless it. Only then might Mass be celebrated here. Their plea to use the temporary wooden chapel in the interim was flatly denied. In 1750 Pedro Anselmo Sánchez de Tagle, Bishop of Durango, wrote to Vicar Roybal to find out whether the settlers of Tomé had acted on the license issued in 1743. If they had, Roybal was to bless the church forthwith. They acted soon enough. The structure, fronting west toward the river with its back to the Manzano Mountains, was up by 1754. So Roybal blessed it. Because it was not yet supplied with all of the required ecclesiastical furnishings, he gave the residents four months' grace and permission to collect alms throughout the district. In 1760 Bishop Tamarón found everything in order. The church, "spacious and decent," measured 8 by 33 varas. It had a transept, three altars, and quarters for the priest, who rode down from Albuquerque. Tamarón thought Tomé had a particularly bright future "because of its extensive lands and the ease of running an irrigation ditch from the river, which keeps flowing there." [3] Trouble was, sometimes the flow proved too much. In the year 1769, Father Domínguez related, "the river flooded (turning east) the greater part of Tomé, to the total destruction of houses and lands. It follows this course to this day, and as a joke (let us put it so), it left its old bed free for farmlands for the citizens of Belén, opposite Tomé." [4] In the late 1820s Tomé's resident parish priest, don Francisco Ignacio de Madariaga, was at his wit's end. The church was in danger. Every year since 1821 he had appealed in vain to the town council to do something about "the indecent and unseemly" condition of the building. The obvious solution was to rebuild in a safe place away from the river. But his parishioners did not want to pay building assessments. Finally he threatened to inform the diocese and have the church closed. The council acted. Governor Manuel Armijo approved. Both church and plaza would be moved to higher ground. And any parishioner who refused to join in the work would be fined twenty-five pesos. Upriver the people of Valencia, part of Tomé parish, refused in a body, saying that the church showed not even a crack. Deadlocked, the dispute was handed over to arbitrators, who decided in favor of relocation. "The church at Tomé," they found in November 1828, "cannot survive, on the one hand because of its deteriorated condition and on the other because of the threat it suffers annually from the river. They reached the same decision concerning the plaza and other houses of its residents." [5] A year later an ecclesiastical visitor from Durango complimented the parish on its contribution of vestments and on building a new open-air cemetery in conformity with the law. He hoped the same religious spirit would move them to get on with relocating the church "so as to avoid the anguish and hardships suffered in the past on account of the flooding river and the lakes that it forms." Bishop Zubiría in 1833 was even more pastoral, reminding the flock of Tomé that their earthly labors on God's house would open up heaven and bring down upon their fields the blessings of that very same God "who makes men rich." Meanwhile, they had better see to the roof of the present church.

The Tomé church was anything but closed on the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin, September 8, 1846. By coincidence General Kearny and his command rode into town the evening before. The Americans estimated that two to three thousand locals had converged on the village. Luminarias, "pine faggots," illuminated church and walls.

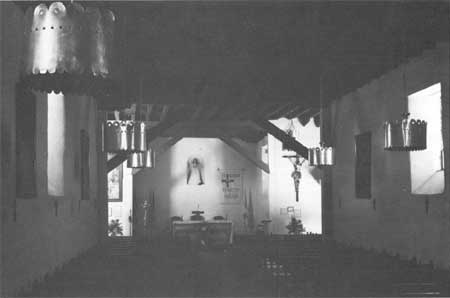

A dozen years after United States occupation, Jean Baptiste Rallière, a twenty-six-year-old French immigrant priest, was assigned to Tomé. He stayed a lifetime. Bishop Lamy thought enough of the young man's potential in 1868 to recommend him in third place as bishop of the proposed vicariate apostolic of Arizona, citing as qualifications "highest honors at the Clermont seminary though holding no academic degrees, eleven years a most successful missionary in New Mexico, spoke French, Spanish, English, Latin, Greek, efficient pastor of souls, excellent health, honest, discreet, prudent, never anything in his actions against moral principles, built several churches and schools." But the job went to Jean Baptiste Salpointe, and Rallière, the gentleman farmer-priest who presided over orchard and organ, woodworking shop and wine press, lived on and on and on at Tomé. [8] Father Rallière had a special fondness for woodworking. He patronized carpenters and carvers. Among the former, Francis Folanfant, his countryman, did a number of jobs for him on the Tomé church. In 1861 Folanfant reroofed the structure and fashioned in the Greek revival style of the day three altars, a confessional, new doors, and a choir loft with railing. New pulpit and main altar, chancel rail and sanctuary arches followed in 1865. The date and building details of the oversize bell towers projecting out from the facade are not known. Rallière did order a large bell from St. Louis in 1863. The similarity between the pseudo-Gothic Tomé belfries, with their wooden louvers and other embellishments, and the all-wooden belfries on San Felipe Neri in Albuquerque, which seem to have gone up about 1865, is striking, surely the result of more than coincidence. [9] The river continued to worry Father Rallière as it had his predecessors, and with good cause. In 1884 it spilled over its banks and spread out across the whole plain at Tomé. The priest ordered santos and movable furnishings carried out of the church. The famous Tomé Christ in the Sepulcher, still lying in the south transept today, refused to leave, so the story goes, becoming suddenly so heavy that the men could not budge it. "That section of the church did not fall although the walls of the nave were so damaged by the two feet of water covering the town that shortly after they required rebuilding." [10]

The Santa Fe New Mexican reported six hundred persons homeless in the flood of May 23, 1905. Once again Tomé was completely inundated. "Tomé is one of the old settlements in New Mexico," the newspaper avowed, "and there is a church there that is almost as old as the San Miguel church in this city. Last night the water was standing at least six feet deep in this church and it is feared that it may be ruined." In 1920 another deluge "caused the nave and facade to collapse; both were rebuilt." [11] For 225 years the people of Tomé's place have challenged the river and refused to move their church to higher ground. Time and again they have paid a price. Probably not 20 percent of the fabric is original, and that part is hidden from view in the mass of the walls and foundations. But the church is still there, today without belfries, flanked by a little glass-front museum and a cement stage for the annual pageant. [12] God and the dams upriver willing, it may yet be, or some part of it, for another 225.

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||