|

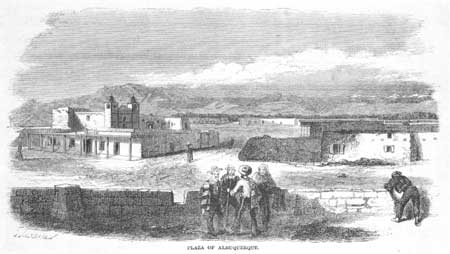

Albuquerque Lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike remembered Albuquerque. That was the place the priest had tried to compromise his republican virtues, to convert him to Roman Catholicism. He remembered the priest, too, fifty-five-year-old Fray Ambrosio Guerra, who hailed from the Atlantic fishing port of Noya near Spain's northwestern tip, a missionary in New Mexico since 1778. Father Guerra had become an institution. Pike's recollection of the welcome extended by the cordial Franciscan on March 7, 1807, lost nothing in the telling. Led first by Fray Ambrosio "into his hall" and, after some refreshment, "into an inner apartment, where he ordered his adopted children of the female sex, to appear," Pike noticed two young girls whom he took to be English. They had been ransomed from Indians as infants, Father Guerra explained. They knew neither their names nor their native language. Nevertheless,

Fray Ambrosio Guerra had come to Albuquerque as pastor in 1787. The church at that time, the same single-nave building with bare earth floor and "gloomy" aspect scrutinized by Domínguez in 1776, seems to have sat at the west end of the plaza facing east with its back "about two musket shots" from the Rio Grande. It, or a predecessor, had been at this location ever since the founding of New Mexico's third villa in 1706. By April of that year a "very capacious and decent" church was reported already built, which probably meant that work had begun the year before. The fines of several local residents in 1718-19, to be paid in adobes delivered at the church site, bore witness to later building. But by Father Guerra's day the Albuquerque church of San Felipe Neri was about to fall in a heap. [2] There was another problem. He was spending half his time in the saddle. From Lower Corrales and Alameda in the north all the way downriver to Sabinal, 50 miles of bosques, ranchos, placitas, and settlers, he and Fray Cayetano José Igancio Bernal of Isleta pueblo were the only priests. In 1790 they reported the combined population of the area at 4,740 souls. They also suggested a partial solution. Adopted and proclaimed by Governor Fernando de la Concha on February 18, 1793, it called for a new mission at Belén. The eager Father Bernal, Franciscan custos at the time, closed the books on his thirteen-year ministry at Isleta and founded the mission of Nuestra Señora de Belén all in the same day, March 22, 1793. According to the redistricting, he would minister to every one from Los Chávez to Sabinal on the west bank and from Valencia to Tomé on the east bank. The new friar at Isleta would still care for Los Lentes and Los Padillas. And Father Guerra of Albuquerque would gain Pajarito and lose Valencia, San Fernando, and Tomé. At least that was the plan. Meantime, he lost his church. "The collapse of the church at Albuquerque is a public disgrace," Governor Concha continued,

The new larger, cruciform church being laid up at Albuquerque in 1793, and evidently begun before that, rose on the north side of the plaza, where it still stands, much modified. From an inventory drawn up in 1796, on which Father Guerra noted simply "Church and Convento—They are New," it appears that he had salvaged from the old sanctuary the large and seemly altar screen painted in oil on canvas. Among the church's ten statues in the round, he listed a St. Francis Xavier, unofficial patron of Albuquerque for much of the century, but still no St. Philip Neri, the patron whom Domínguez had verified in 1776 and ordered venerated. [4] Guerra's burden did not ease. Between 1790 and 1800 hundreds of new parishioners were born or moved into the area. Redistricting had taken place only on paper. The communities on the east side of the river as far as Tomé remained within his parish. The Tomé church, more than 20 miles south of Albuquerque, was an auxiliary of San Felipe Neri, as was the chapel at Alameda, 7 miles north. The friar's unflattering description of his flock in 1801 probably reflected overwork as well as his feeling of superiority as a peninsular Spaniard. They were, he said, "mainly genízaros (which is a mixture of various tribes), mulattos, coyotes, and few Spaniards although most consider themselves such without being it." He wanted to improve their knowledge of the faith, but his hands were tied. As an interim parish priest he could not force them. "I can do nothing but expound it at the altar, having no other means. As a result one encounters much laziness and ignorance, and there is no other remedy but silence." [5]

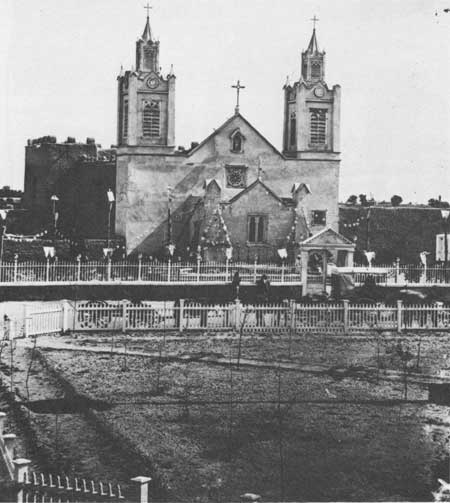

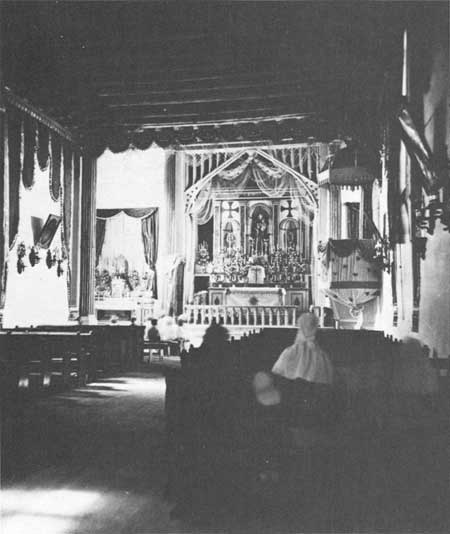

A half-century later Bishop Lamy sought to apply the remedy. More than the Albuquerque congregation in 1852, it was their patriarchal, loose-living merchant-priest don José Manuel Gallegos who tried the new prelate's calm. When Gallegos returned from an unauthorized absence in Mexico he found himself suspended in favor of Lamy's feisty little lieutenant, Joseph P. Machebeuf. On Sunday morning the two priests clashed verbally in front of the altar and, in Machebeuf's words to his sister in France, the outclassed Hispano had to "slink away like a fox." Like his counterpart in Santa Fe, Gallegos tried to hold on to his comfortable quarters in the convento, claiming that the bishop of Durango had sold them to him personally. That issue too was decided in favor of the Frenchmen. While the influential Gallegos got himself elected and later unseated as New Mexico"s delegate to Congress, Father Machebeuf and his countrymen set about repairing and redecorating San Felipe Neri in a style that looked to their eyes more churchly. [6] Lamy was pleased. By 1860 he considered the Albuquerque parish church one of the fairest in his diocese, which, as he would have been the first to admit, was not saying much. Still, Machebeuf had "put on a new roof, floored the church with boards, and built a sanctuary and a new altar." To the Reverend Carlos Brun the bishop gave credit for "many paintings on the ceiling (en el techo) and in the sanctuary." It was Machebeuf again, according to Prince, who had the narthex built out front, and the Reverend Johannes Augustus Truchard, famed for his resonant bass voice, who directed the installation of a new pulpit and sounding board. After Italian Jesuits imported by Lamy from Naples assumed administration of the parish in 1868, they took pains with fancy woodwork, tin, and paint to imitate the marble Baroque interior of the Gesu, the order's mother church in Rome. They began building too, six additional rooms on the convento, a corral, stables, chicken coops, and a new sacristy, ordering between late 1870 and mid-1873 some 60,000 terrones, those Río Abajo sod blocks that serve as adobe substitutes. [7]

Routine maintenance, as always, kept its place on the church calendar. The first Sunday in Advent, 1868, the Reverend Rafael Bianchi, S.J., made a familiar appeal.

The Jesuit's plea paid off. Lieutenant John Gregory Bourke, thoroughly inured to "the damp dark mouldy recesses" of New Mexico church interiors, was in for a pleasant surprise at San Felipe Neri. Like Francis Bacon and John Wesley, a firm believer in the proximity of cleanliness and godliness, Bourke found here in November of 1881 a godly structure.

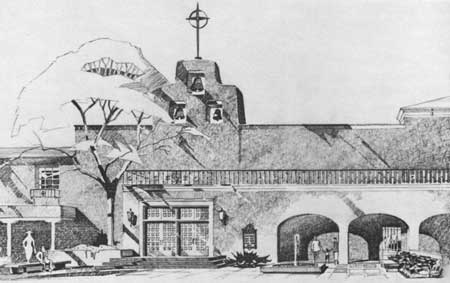

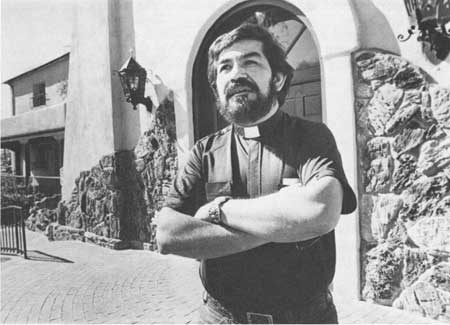

The boldest expression of San Felipe Neri's "Victorian" new look was the matching set of elongated, two-tiered, imitation Gothic belfries, already in place by the mid-1860s, before the Frenchmen had left. They had literally changed the skyline, if Albuquerque's low adobe profile could have been properly termed that. Depending upon how one felt about the mixing of styles and the accretions of time, the effect was either charming or God-awful. Either one saw how "the light wooden towers effectively contrast with the solid adobe facade" and admired "the lacy decoration," or he damned this "rather poor bit of Ohio, Neo-Gothic stuck onto a more than usually ordinary adobe church." Both views were heard in 1966 during an emotion-charged controversy over whether to remodel the building drastically. The alleged need to increase its seating capacity and to bring the structure into conformity with the dictates of Vatican II supplied the modernizers with a potent argument. "Buildings," especially churches, they proclaimed, "are made to serve people—rather than the reverse." On the opposite side the uniqueness of San Felipe Neri in a city short on monuments to its past, and the previous historical zoning of Old Town, emboldened the preservationists. They won. When the church was solemnly rededicated in 1972 it boasted a new brick floor, a restoration of the old rooms against the east wall, and a general cleaning and plastering. The famous belfries, symbolic of the struggle, had been taken down with the aid of a giant crane, repaired, and replaced for future generations. [10] Stuccoed in pastel orange, sandwiched between late nineteenth-century, two-storied convent and rectory, the church of San Felipe Neri remains today an object of active parish life, tourist curiosity, and disagreement. There are those who wish that the structure had been stripped of its Victorian elements during the renovation and given back "its mission look." Some preservationists object to the buttressing of the narthex and to the walled patio built out front in 1975. When the Rev. George Salazar, pastor of San Felipe, allowed some hasty exterior repairs in March 1978, he was cited promptly for violating the city's historical zoning ordinance. The debate resumed: a local congregation's right to worship in freedom and privacy versus the people's right to preserve their historical heritage. Meantime, a thousand tourists' snapshots recorded the artificial stone work which makes the front door look like the entrance to a grotto. [11]

A remarkable composite, this continually changing temple will never satisfy the purist. In it Hispano New Mexican, Italian Jesuit, and French immigrant all are represented. And somewhere up there between pressed tin ceiling and pitched tin roof are the double corbels of Fray Ambrosio Guerra's 1793 building. At least they are preserved. Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||