|

Sandía Pressing northward from Isleta in the December cold of 1681, Governor Otermín's second-in-command saw in the distance a large cloud of smoke rising from the pueblo of Sandía. A scout told him that the retreating Indians had set fire to a corral. Next day when he reached the pueblo himself the Spaniard "found burning the chapel that had been dedicated to the most glorious St. Anthony. In the convento only three cells remained. These, it appeared, they had left with particular care for diabolical dances, since in one of them they had a forge rigged up and in the other two had placed a large number of masks used in said dances. All of the main church was burned and the convento demolished. He found this pueblo deserted except for one blind Indian, who, being asked about the people of said pueblo, responded that all of them had fled to the sierra." [1] Diego de Vargas, who found Sandía uninhabited and in ruins eleven years later, proposed resettling the site with Spaniards. "The walls of the church and some houses," he reported, "although badly damaged, may be repaired." Eventually, after more than half a century had passed, Sandía was resettled, not with Spaniards but with descendants of the Southern Tiwa Indians who had left here and the neighboring pueblos for exile among the Hopis. Some Hopis came with the returning refugees. Always a minority, the Hopis of Sandía continued to speak their own language and to live apart, in Father Domínguez's day, "in some small, badly arranged houses above the church to the north." Fray Juan Miguel Menchero, an irrepressible Franciscan promoter who had his irons in every fire from mission supply to military campaigns, managed details of the resettlement. It took place in May of 1748 under the advocacy of Our Lady of Sorrows and St. Anthony. The site, 14 miles north of Albuquerque on the east side of the river, was the same as in the previous century. Evidently, if Domínguez had his facts straight, Menchero wanted to rebuild the pre-Revolt church. And he failed. "On the inside," said Domínguez, "and joined to the old walls there are some half walls of adobe which Father Menchero built with the intention of restoring the church to its former state. But he soon realized that it was useless and that everything was going to fall flat together. So it remained as it was. It faces east and has two small towers dating from that time." [2] Late in 1751 Father Menchero was in a quandary. It had been three and a half years since the resettlement, yet Sandía was still without a proper church. The walls were up. And he had seen to the cutting of roof timbers in the mountains. But there they lay. The Indians of the pueblo had no oxen to drag the heavy beams down to the valley. Nor were they particularly inclined, "considering the short duration of their descent from the Province of Hopi and of their settlement at this place under discipline." The neighboring Spaniards of Bernalillo, parishioners of the mission, had no oxen either. What was Menchero to do? If the beams were left on the ground they would rot. If he waited much longer, winter snows would impede the hauling. He had an idea. The Keres pueblos of San Felipe, Santo Domingo, Cochití, Santa Ana, and Zia had plenty of oxen. As loyal vassals of the king and good Christians, why should these Indians not lend a hand, or an ox? Governor Tomás Vélez Cachupín could see no reason. On January 3, 1752, he ordered local officials to notify the men of the five pueblos to assemble at Sandía on the day set by Father Menchero. The Indians were to provide a dozen yoke of oxen from each pueblo and to stay until every timber was dragged down. The Spaniards of Bernalillo were also to aid in the work, under threat of a twenty-five-peso fine applied to the building fund. Menchero, it seemed, had solved his immediate problem. The resultant roof, however, was poorly engineered or shoddily built and proved less than a lasting monument to his enterprise. Barely twenty years later, it fell in. [3]

Open to the sky in 1776, the Sandía church was "unusable, being in such a deplorable state that it truly saddens the soul to see the marks of the barbarities they say have been perpetrated here." In its place the missionary was using the low-roofed old baptistery, which jutted 12 varas north, flush with the facade, reminding Domínguez of a coach house. The following year, 1777, the Father Visitor had to confirm another contract entered into by his nemesis Fray Sebastián Ángel Fernández, the friar trader. By it a layman, don Cristóbal Vigil of Santa Cruz de la Cañada, obligated himself

It must have proved more of a job than Vigil had bargained for. The terms of the contract stated that he was to finish in two years, or by April 18, 1779. Yet according to Father Pereyro, the church as well as a convento not stipulated in the contract "were built in 1784," the same year Fray José Palacio paid for painting the altar screen. In the next decade, too, there was construction. A 1796 inventory recorded that "church and convento are in good shape, now that the building is finished." [5]

By the 1860s both were in bad shape, falling gradually to ruins for the last time. The weathering took decades—even today mounds and low walls mark the spot. As late as 1915, Judge Prince could write that relics of the walls still stood well above his head.

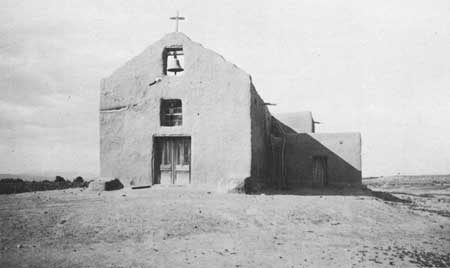

Confronted with the lingering demise of their historic church, the people of Sandía had opted for a new location, a slight rise a hundred yards east of the old one. The modest cruciform adobe building would have no convento, for the priest now lived in Bernalillo. In fact when he blessed the new church, Father Tomás de Aquino Hayes entered notice in the Bernalillo parish burial register. On Epiphany, January 6, 1864, "I, Presbyter Tomás Hayes, parish priest, having been authorized by the Most Illustrious Lord Bishop of Santa Fe don Juan Lamy, blessed and inaugurated the church of Nuestra Señora de Dolores y de San Antonio de Sandía in accordance with the Roman ritual." [7]

The patron saints of Sandía and nearby communities need sorting out. About 1610, the year he arrived in the colony, Fray Esteban de Perea had founded the first mission at Sandía, choosing as patron Our Father St. Francis. Here, in the sturdy convento, with Perea as reluctant jailer, New Mexico's governor, don Pedro de Peralta, was held captive for nine months by order of the crazed Fray Isidro Ordóñez. Down to 1680 St. Francis presided at Sandía, although at some unrecorded date a chapel dedicated to St. Anthony of Padua had been added to the church. St. Anthony was also patron of Isleta downriver. During the revolt of 1680, the Pueblos had sacked and burned the church of St. Francis at Sandía, leaving intact for their own purposes the chapel of St. Anthony. Then, as Spaniards approached late in 1681, they had set fire to the chapel. For more than sixty years, Sandía lay deserted. Spaniards had moved back into the area. At Bernalillo, 5 miles north, the Franciscans maintained a church and convento in the early years of the eighteenth century. For patron of Bernalillo they had borrowed Our Father St. Francis. Meantime, in 1710, the friars had reestablished the mission of Isleta under the advocacy of St. Augustine, leaving St. Anthony free. It was a game of musical saints. Refounding Sandía with two patrons was Father Menchero's idea. St. Anthony, titular of the seventeenth-century chapel, already had a claim. For good measure the enterprising friar added Our Lady of Sorrows, whose feast, the Friday before Good Friday, fell in 1748 on April 1—just when Menchero was drawing up his petition to the governor. It has been suggested that the Indians of Sandía considered St. Anthony their particular patron all along, and that the Hispanos of Bernalillo, for years a visita of Sandía, favored Our Lady. And that is the way it has worked out. Today, with their roles reversed, the parish of Our Lady of Sorrows at Bernalillo has as a mission the church of St. Anthony at Sandía. [8]

Sandía's "new" church, after 112 years, several facade alterations, and at least two roof changes, underwent in 1976 a renovation and face lifting. The effort was funded by a $4,000 grant from the New Mexico Bicentennial Commission. A Sandía spokesman told The Albuquerque Journal "that although he did not agree with the commission philosophy that promotes past events where Indians were losers, he asked for funding from the commission because it was the only source of funding he could find." [9] Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||