|

Santo Domingo Everyone liked the view from the Santo Domingo church. Standing on the balcony in 1776, Father Domínguez found it "very pleasant." Lieutenant Pike, on the roof in 1807, "had a delightful view of the village; the Rio del Norte on our west; the mountains of St. Dies [the Sandías] to the south, and the valley round the town, on which were numerous herds of goats, sheep, and asses; and upon the whole, this was one of the handsomest views in New Mexico." From the same vantage point in 1881 Lieutenant John G. Bourke admired "an expanded and picturesque view of the valley of the Rio Grande." [1] The painstaking Domínguez, having done with his inspection of the Santa Fe churches and those of the Río Arriba north of the capital, next turned his penetrating gaze downriver on the Río Abajo. So as not to upset, as he put it, "the extremely clear and harmonious style of my narrative" or vex his superiors, "to whom humble veneration and the deference of forethought is due," he took up the east-bank communities in sequence, then crossed over and did the same on the other side. Santo Domingo, a Keresan speaking pueblo 25 miles southwest of Santa Fe, was the first. Here he counted six long house blocks in 1776, laid out not around a single central plaza, but rather with two to the west of the church and four due south of it in parallel rows "with their backs to the church and convent." A "rather high" adobe wall surrounded the entire community, which lay, Domínguez noticed, "very near the Río del Norte." For much of the previous century Santo Domingo had been the headquarters of Franciscan New Mexico and the residence of the Father Custos. The library and archive, stuffed in large chests, were still kept here. The meticulous visitor in fact admonished the missionary to make certain that no friar checked out a library book without first signing for it. [2] The Santo Domingos had enlisted in the Revolt of 1680 with zest. During Governor Antonio de Otermín's bootless attempt at reconquest in the winter of 1681-82 they temporarily vacated their pueblo for fear of reprisal. One of the Spanish officers recalled the scene. From the pueblo of San Felipe

Presumably the rebuilt stretch of wall be longed to the pre-Revolt church and convento at Santo Domingo. Whether any part of it was reused in the makeshift structure of the 1690s, or in the one Domínguez called "the old church," is uncertain. At any rate, about mid-century, Fray Antonio Zamora, a native of Mexico City who had come to New Mexico around 1740 and was "incapacitated" by 1762, had another larger one built and decorated at his own expense. Thus in 1776 Santo Domingo had two churches, side by side facing south, an old one relegated to burials and passage to and from the convento, and a thick-walled newer one, both "in full view of the Río del Norte." [4] An unsigned inventory drawn up three decades later, in 1806, revealed that Father Zamora's church had "just been repaired, well roofed with boards, the vigas very striking with their corbels and carved decorations. Arranged at the high altar are the following images: first, one of Our Father St. Dominic in the round, a vara and a half tall and very handsome. It is set in its niche with its curtain of red ribbed silk which hangs from an iron rod with rings." The statue was the same one admired earlier by Domínguez, but a red curtain had replaced the old blue one. [5] Zebulon Pike, the first Anglo visitor of record, was astonished a year later

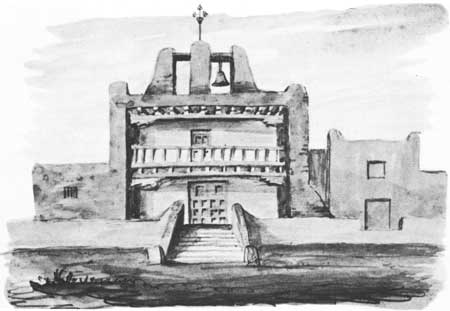

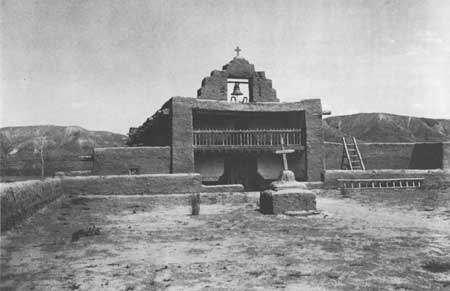

In 1846 the Santo Domingos feted General Kearny. The Padre, don Rafael Ortiz, "a fat old white gentlemen," entertained the officers in the convento in his "parlor, tapestried with curtains stamped with the likenesses of all the Presidents of the United States up to this time," a sure sign that commercial conquest had preceded the soldiers. The wine was good enough and the sponge cake superb. [7] That October, when the upper story of the house blocks was "covered with strings of red peppers and long spiral curls of dried melons and pumpkins," Lieutenant J. W. Abert sat in front of the Santo Domingo churches sketching. His watercolor portrait squared neatly with Domínguez's word picture of seventy years earlier. The carved door panels of "singular armorial bearings" particularly interested the young officer. An Episcopalian, he was versed enough to identify the one on the left as the Dominican cross, while the one on the right, "a plain cross standing on a globe, two human arms, and these also surmounted by a crown," he failed to recognize as the insignia of the Franciscan Order. Later, when new doors were hung on the main church, these weathered ones were apparently cut down in size and placed at the entrance to the old church, where Adolph Bandelier had his picture taken in 1880. [8] Inside, Abert mistook the carved wooden St. Dominic for wax. He had time enough to copy the long inscription from a painting of Santiago. Lieutenant A. W. Whipple, taking the tour in 1853, was not as fortunate.

Some years before the bumptious Bandelier slept in the convento at Santo Domingo, the flooding Rio Grande had washed away the western end of the pueblo. At the foot of the bluff were two levees "to keep off the current, should the river overflow." The receding edge was not that far from the church complex, which, according to Bandelier's ground plan of Santo Domingo in 1880, now sat almost on a promontory.

It was ironic that the great Swiss-American ethnologist, just beginning "the dream of a life," had chosen as his first live Indian pueblo for study Santo Domingo, the most tradition-bound and secretive of all. In just nine days he wore out his welcome. Rushing about, part of the time with Santa Fe photographer George C. Bennett in tow, peering down into the kiva, measuring and sketching, asking questions, he did make his short stay count. The adobes of "the old church" measured 27 by 35 by 8 centimeters, with 6 centimeters of mud between. When anything needed doing about the church, the sacristan alerted the fiscal mayor and the latter detailed his lesser fiscales to see that it got done. "Two churches, old, very interesting. Fine library of Dominicans [Franciscans]. Bells, old and new. Remnants of wooden sculptures." Several days later he added to the picture.

Lieutenant Bourke, who managed to get himself bodily ejected from the kiva on August 4, 1881 jotted down his usual Waspish observations about the churches and their contents. The music "of cracked fiddles, squeaky guitars, bell, drums, and rusty shot-guns"—which can still be heard at Santo Domingo—was almost as popular a subject with visitors as the view. Bourke also inspected the "laborious and expensive revetments" intended to channel the river away from the bluff. Many of the residents, he said, "have taken counsel with their fears and constructed new houses farther inland, making the Pueblo a double town." [11] For the next five years, in Bandelier's curt journal entries, one can almost see the river's muddy waters rise with each summer runoff to assault the base of the crumbly dirt cliff, then fall back again. "July 2, 1884 ... At San Felipe the water has risen but little, but at Santo Domingo it reaches the foot of the bluff on which the western tiers of houses stand. It looks rather threatening." The following summer the Santa Fé New Mexican Review headlined a special bulletin "The Raging Rio Grande About to Take the Church at Santo Domingo." The current was cutting away at the earth at a great rate. A large work force under Pueblo Governor Santiago Chávez was trying to turn the waters and save the church. The railroad had donated rock for the dikes, but, in the reporter's opinion, the situation was hopeless. "It is believed the structure is as good as lost." Then the river dropped.

Studying the archives at San Felipe pueblo, Bandelier found an account of the missions of New Mexico dated 1831. It told of disastrous floods in 1780, 1823, and 1830. The river in 1830 had claimed two churches and two conventos, although the document did not say which ones. From his own observations it appeared to Bandelier that he was about to see history repeat itself.

That was the last warning. The Santo Domingos, men and women, tried, in the words of the Albuquerque Morning Journal, "to defeat the river god, but without success." Resigned at last, they took off the doors, carried out the paintings, statues, and everything movable from both churches and the convento, including the books from the library. Then they stood back to watch.

On Thursday morning, June 3, 1886, the same day the Santa Fé Daily New Mexican ran an item on the drought in southwest Texas headlined "Pray For Rain," the earth began washing away under the Santo Domingo church. Raging from the north across submerged levees of trees and rock, the water cut in first beneath the right-rear corner of the main structure, then proceeded both forward and to the left, claiming in turn the older church and finally the convento. Roof vigas writhed awkwardly as sections of wall gave way under them. The cemetery fell away too, and the people watched the shrouded remains of their dead slide off into the churning waters. Eventually only a steep bank was left. [13] For a decade the Santo Domingos did with out a church. But they must have a church, insisted the young Frenchman who became their priest on January 1, 1894. Noël Dumarest, born Christmas Day of 1868 in Lyons, had come to Santa Fe on the Fourth of July, 1893. As pastor at Peña Blanca he ministered also to the Indians of Santo Domingo, Cochití, and San Felipe. Indians fascinated Dumarest. He was in fact an ethnologist in cassock. Like Bandelier, he learned quickly that his queries made him unwelcome at Santo Domingo and chose instead to study Cochití. Nevertheless, he urged the Santo Domingos please to build a church. That they agreed to do, on high ground well east of the pueblo, around 1895. Judging from the improvements of Father Camille Seux, another transplanted son of Lyons, upstream at San Juan, one might have expected the new Santo Domingo church to rise with peaked windows, gabled roof, and slender white steeple. It did not. It very much resembled the one washed down the river. Even if he had wanted to, Father Dumarest was simply too young and too new to sell the conservative councils of Santo Domingo on a "modern" design. They wanted something that looked to them like a church, not a little Lourdes. Like most adobe structures, Santo Domingo's new church looked as though it had been born old. Still, because of its comparative youth in 1915, L. Bradford Prince called it "a creditable and commodious building, but of course with out historic interest." Late in the 1970s, a well-preserved eighty years old, it is of undisputed historic interest. [14] Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||