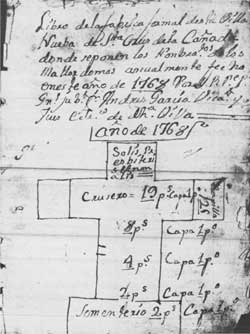

|

Santa Cruz de la Cañada Here at Santa Cruz, on the west side of an unadorned dirt plaza hemmed in by asphalt roads, is the biggest church Father Domínguez saw in New Mexico in 1776. With the exception of Las Trampas, it is the only church he inventoried north of Santa Fe that still stands. [1] Diego de Vargas himself founded the Villa Nueva de Santa Cruz de la Cañada, upriver New Mexico's second formal municipality. The location, a fertile valley about 20 miles north of Santa Fe, was particularly desirable. Spaniards had farmed and run stock here before the Revolt of 1680. Afterwards Tano Indians moved in. But Vargas, basing his claim on prior Spanish occupation, relocated the Tanos and on April 22, 1695, with due pomp and flourish, put some sixty families of settlers in possession. He also gave over to them a chapel the Indians had built. It would serve, he said, until they "rebuilt" their church. During the uprising of 1696, caused in part by the rude displacement of the Tanos, Vargas used Santa Cruz as a base. Most of the settlers got out. When they returned they moved the seat of the community from among the ruins of the former Tano pueblo of San Lázaro on the south side of the Río de Santa Cruz over to the north bank, where it has remained ever since. By 1706 they had "a small church and a bell." Here in 1730 Bishop Benito Crespo of Durango, the first bishop to set foot in the colony, noted that the church had been "built at the expense of its Spanish citizens." He wanted it entered in the record that this, like the Parroquia in Santa Fe, was no mission church erected with royal subsidies to the Franciscans. Still, because the bishop was in no position to supply a secular clergyman of his own, Franciscans from one of the nearby Tewa missions continued to look after it. By 1732 the church at Santa Cruz was on the verge of collapse. [2] Fray José de Irigoyen of San Ildefonso had a plan. Because a new church for Santa Cruz could be considered a public works project for the good of the colony, he would employ Indians. First he had to have the approval of Governor Gervasio Cruzat y Góngora. The governor balked. The friar had made no provision for funds or materials, and he had not secured a building permit from Mexico City through proper channels. When Cruzat came to Santa Cruz on his official tour of inspection he had to agree. The old church was in miserable shape, "beyond repair and in danger of collapsing." Still, regulations were regulations. He would write for the viceroy's permission. That took a year. [3] Don Juan Esteban García de Noriega, alcalde mayor of the district, had the viceroy's permission proclaimed at Santa Cruz on June 21, 1733. Father Domínguez gave García credit for the church, but just when he got round to building it is unclear. Construction seems to have been done in sections. As late as 1744 a Franciscan superior declared that the resident minister at Santa Cruz, probably Fray Antonio Gabaldón, "is now building a sumptuous church by order of my prelates, without its costing his Majesty half a real for its materials or building." Since Domínguez attributed most of the convento to Gabaldón, the job was probably in its final stages. Bishop Tamarón, sweltering in June 1760, found at Santa Cruz no semblance of a town. The 1,515 Spaniards and mixed-bloods were scattered up and down the valley. Their church, he admitted, "is rather large but has little adornment." [4] That very lack of adornment struck the veteran forty-five-year-old Fray Andrés José García de la Concepción as a challenge. He was one of the few known eighteenth-century Franciscan artists in New Mexico, a wood-carver and painter in a "rather sweetly conservative style." Assigned to Santa Cruz between 1765 and 1768, Fray Andrés set about to dress up the place. He fashioned a decorative altar rail, an altar screen, and a variety of carved images, working, said the locals, "day and night with his own hands." The urbane Domínguez, who acknowledged García's industry, considered the results ugly. One example of the friar-artist's work, the Santo Entierro, can still be seen in the nave at Santa Cruz, set into an alcove on the left side: a gruesome blood-spattered Christ lying on pillows in a casketlike, see-through sepulcher. [5] There were some major changes at Santa Cruz in the two decades after Domínguez. The unique ceiling over the nave, five triple crossbeams with vigas running lengthwise of the church between them, had to be replaced in 1783 at the expense of the controversial builder-friar, Sebastián Ángel Fernández. Fray José Carral, pastor between 1784 and 1789, had a chapel for the Third Order of St. Francis built off the south end of the transept, where the old sacristy-baptistery had stood. It counterbalanced the chapel of Our Lady of Carmel stepped off by Domínguez on the north end. A door from the Third Order chapel led into a spacious new sacristy and on into the new baptistery "with its altar and painted wooden door with iron bolt." To replace the run-down convento Fray Ramón Antonio González, probably in the early 1790s, underwrote the cost of seven new rooms "upper and lower." Another of Father Carral's contributions was a fine, large, long-waisted bell sent from Mexico in 1789. For well over a century it rang out over the valley, until the pastor in 1928, with the consent of Archbishop Daeger, sold it to the Fred Harvey Company. [6]

Proper, Protestant, and twenty-eight, Lieutenant Zebulon Pike of New Jersey ignored the big church at Santa Cruz. Passing through on March 3, 1807, under escort, he did mention a stop at "the house of the priest, who, under standing that I would not kiss his hand, would not present it to me." Another priest came in, a young man. His comportment shocked Pike: "strutting about with a dirk in his boot, a cane in his hand, whispering to one girl, chucking another under the chin, and going out with a third, &c." [7] Back home such behavior would have caused a minister to be drummed out of the clergy. Eleven years later, when the ecclesiastical visitor from Durango was touring New Mexico, the young priests watched their step. At Santa Cruz don Juan Bautista Guevara reacted to the accumulation of "very indecent" art by banishing six paintings on hide, condemning the crown of hide worn by a life-sized Jesus Nazarite, and ordering a smaller image of the same to be burned. In the manner of Domínguez a generation before, Guevara took measurements poked into every corner, and noted that Christ in the sepulcher was minus two fingers. Guevara's word picture of the cemetery helps identify the mass of construction that showed up in photographs from the 1870s out front of the church.

Don Agustín Fernández San Vicente, writing in 1826, only eight years after Guevara, added several details and pointed to more building.

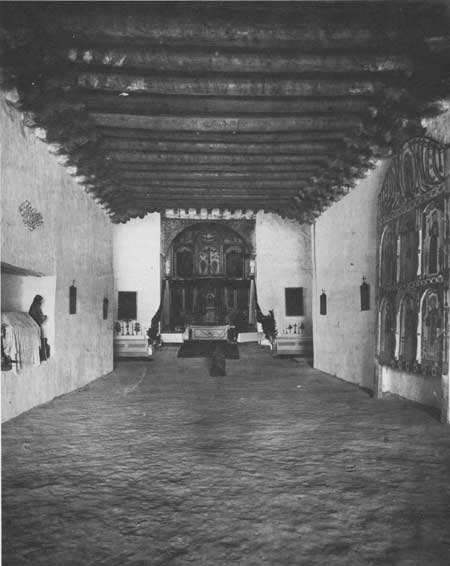

Proper, Catholic, and thirty-five, Lieutenant John G. Bourke of Philadelphia missed the day of Corpus Christi at Santa Cruz in 1881 but was there on July 16, the feast of Our Lady of Carmel. At the forage agency the evening before, he shared a hurried supper of "broiled kid, bread, coffee, fried eggs and green lettuce" with Fathers Jean Baptiste Francolon and Ramón Medina, then he followed them across to the church for vespers. He made no mention of the cemetery enclosure, which was even then wasting away, nor of the rapidly disappearing exterior embellishments by some homesick French men. In the previous decade photographer H. T. Hiester had recorded the folly of someone, either the Rev. Jean Baptiste Courbon, pastor from 1869 to 1874, or the Rev. Lucien Remuzon, 1875 to 1880, who had not worked with adobe before. One or the other tried things that must have set the locals agog—a row of pointed, open, tentlike merlons atop both side chapels; thin ornamental arches on either side of the pediment surmounting the facade; horizontal stacks of rounded adobes laid side by side to form a parapet all the way around the outer wall of the cemetery. A waste of labor, utterly impractical in friable dried mud, yet the effect had been marvelous. [9]

Noticing the lieutenant's presence, Father Francolon placed a chair for him near the altar, "a courtesy to be fully appreciated only by those who have ever assisted at a Mexican mass or Vespers without a seat or bench upon which to rest at any moment during the long service. The discordant guitars, violin, and choir, the volley fired outside the door from old muskets "almost coeval with the Building," and the unaffected devotion of the people held Bourke's interest. Afterwards the priests showed the young officer a collection of old paintings, San Ildefonso pottery, and Spanish documents. One painting that Bourke liked was also coveted by the president of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, who had made a standing offer of $500. That night, in an effort to escape the bugs in his bed, Bourke unrolled his own blankets in the plaza under the stars. He slept well and awakened with the first light in a poetic mood. "The rising sun threw against the sapphire sky the angles and outlines of the old church, bringing out with fine effect its quaint construction and excellent proportions. The waning moon, in mid sky, shed a pale, wan light that grew fainter and fainter as the orb of the day climbed above the horizon:—back of all rose the massive, deep-blue spurs of the Sierra de Chama." [10]

About the turn of the century, the church at Santa Cruz received its multilevel peaked tin roof, a marvel in its own right. In 1920 the first priests of the Congregation of the Sons of the Holy Family arrived from Barcelona, Spain. Invited by Archbishop Daeger to take over the populous, largely Spanish-speaking parish and its missions, they have been here ever since.

There is talk today, as there has been since the 1930s, of taking off the gabled roof, of restoring the old church to create a more historic look. After three generations, however, there are people in Santa Cruz, as well as a number of outsiders, who have actually grown fond of it just as it is. [11]

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||||