|

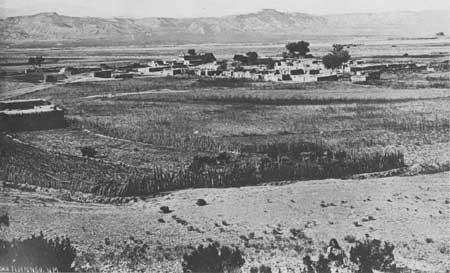

San Ildefonso Charles Fletcher Lummis, that wiry, indomitable little wayfarer of the 1880s, enjoyed himself thoroughly at San Ildefonso. Twenty miles northwest of Santa Fe—a morning's walk for Lummis—this was not, he allowed, one of the larger pueblos, "having but two or three hundred people. It is built in a rambling square of two-story terraced adobes around the plaza and its ancient cottonwoods. The old church and its ruined convent—monuments to the zeal of the heroic Spanish missionaries—doze at the western end of the square, forgetful of the bloody scenes they have witnessed. Here the first pioneers of Christianity were poisoned by their savage flock; and here in the red Pueblo Rebellion of 1680 three later priests were roasted in the burning church. But all that is past."

Just as well. If Lummis had the facts of his story jumbled the spirit was true enough. The Tewas of San Ildefonso indeed had brought down not one but two churches, the first in 1680 and the second in 1696. They had martyred a priest and a lay brother on the first occasion, and they had asphyxiated, if not roasted, two more missionaries on the second, their own Fray Francisco Corvera and visiting Fray Antonio Moreno from Nambé. Diego de Vargas found the bodies four days later. An entry in his campaign journal, dated June 8, 1696, recorded their burial. "I had the Pecos Indians and the soldiers cover them with a wall and adobes the rebels had torn down from the church itself for the reason that they could not be moved because they were whole. The fire had not burned them, but rather the smoke and heat suffocated them because the enemy Indians had cut off the ventilation." [1] Eighty years later Father Domínguez found in the sacristy of a subsequent church at San Ildefonso a piece of paper in a little black frame. It supplied the information he might have expected to find on a dated beam. Church and convento had been "built and founded" by Fray Juan de Tagle and dedicated June 3, 1711. They faced south outside the western block of houses, definitely not an integral part of the pueblo. Fray Juan had come here in 1701, just five years after the execution of Fathers Corvera and Moreno, and he stayed a quarter-century, a most singular record in post-Revolt New Mexico, where missionaries, like the swallows, transferred almost with the seasons.

As much a politician as a minister, Tagle served three terms as Franciscan superior of the colony. He fought mightily with Governor Peñuela, who accused him of the most blatant insubordination, and he embraced Governors Juan Ignacio Flores Mogollón and Antonio Valverde y Cosío, who in return contributed handsomely to the San Ildefonso church. Flores Mogollón gave an oil painting of Our Lady of the Kings, "in a finely gilded frame with a curtain (on a rod) of blue ribbed silk embroidered and garnished with ribbon of another color." But Antonio Valverde, a talented opportunist who served ad interim between 1717 and to the honor of his name saint, San Antonio, very similar to the one that had just been built in the capital for La Conquistadora. It measured 19 by 44 by 19 feet, projected out from the east side of the church, and contained "a carved St. Anthony about a vara high, adobe altar table, and nothing else." [2] Domínguez said that San Ildefonso's church was dark inside, but the convento cloister on the Gospel side he found "pretty and cheerful." The convento here was unique. Its "porter's lodge" was huge, a roofed enclosure 41 feet square, open to the front, with an adobe bench all the way round inside. It was like "an auxiliary church," similar to the open chapels of earlier Franciscan missions in central Mexico. The rest of the building, with its two stories, miradors, cells, and storerooms, had suffered settling and cracking. Almost thirty years after Domínguez's inspection, a young man he had brought with him to New Mexico, Fray José Mariano Rosete y Peralta, whom he soon characterized as "not at all obedient to rule and agitator of Indians," restored the San Ildefonso convento. By that time the church also needed help. [3]

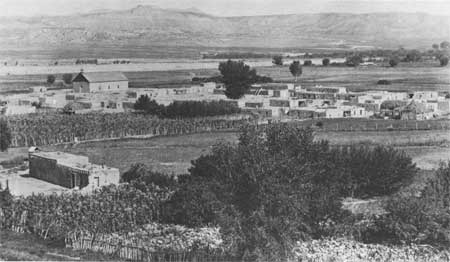

[...missing text...] 1722, outdid Flores. He donated a whole chapel straight-on. "The church is very dilapidated," he commented in 1881, "and the rain runs through the roof in a perfect stream." At least it still stood. The reason was sheer mass: great buttresses of rubble and adobe were piled against it. The two that rose out of the ruins of the old convento to brace the west wall must have measured 20 by 20 feet at the base. They might have been enough but for the human element. Bitter factionalism rent the pueblo, and the church building became an issue. Photographs by Vroman taken in 1899 show that the venerable structure needed repairs, but overall it looked solid. Still a new roof with clerestory that did not leak was a lot of work, and to what end? Would it not be wiser, suggested the padre, to demolish the dirty, unsafe old church and build a modern one? Yes, said one faction inflexibly. Absolutely not, countered the other. An untimely trip to the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904 by leaders of the conservatives broke the deadlock. While they were away, the opposition tore into the church. In 1905 on the same spot there arose a tidy, practical, tin-roofed building that looked more like a large one-room school house than a church.

By the late 1950s a new era of harmony had dawned at San Ildefonso. The houses built Lieutenant Bourke sketched only the facade, across the spacious plaza to divide the South People from the North People came down. About 1957 the tidy practical church, pronounced "beyond repair," also came down. The entire pueblo now joined in a monumental community effort—construction of a reasonable facsimile of the 1711 church. Santa Fe architects McHugh and Hooker, Bradley P. Kidder, and Associates, working with the Vroman photographs and the just-published Domínguez description, estimated that the job would require $75,000 and 80,000 adobes.

It took ten years, from 1958 to 1968. The pueblo's newly united government assessed each family several days' labor as well as a certain number of adobes to be delivered to the construction site during the summer building season. Because no big pines grew on San Ildefonso land, Santa Clara contributed standing timber for vigas. Funds came from sand and gravel sales, leases of tribal lands, the Archdiocese and other Catholic organizations, outside donations, and from an endless round of bazaars and bake sales. Finally on December 15, 1968, the dedication was set. If Father Domínguez could have been there he would have had mixed emotions. He never much liked these New Mexico churches. On the other hand, someone had finally read his report. [4]

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||||