|

Pojoaque As part of the program to replant Pueblo Indians uprooted during the years of revolt and reconquest, Spanish officials in 1707 revived the small, deserted pre-Revolt pueblo of Pojoaque. They peopled it with displaced Tewas and exiled Pecos and they called it the mission and pueblo of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de Pojoaque. But rarely if ever did it number over a hundred souls. The site lay atop a ridge roughly 16 miles north of Santa Fe and only 3 miles down from Nambé on Pojoaque Creek. The view across the valley and beyond to the gray-blue mountains above Taos was spectacular. "This little pueblo," wrote Domínguez, "has been a visita of Nambé in perpetuity." [1] If there was a church at Pojoaque before 1765, it did not rate mention. In that year one Fray José Esparragoza y Adame, resident at Nambé, enlisted the Indians to start building one. Like the Castrense in Santa Fe, it would face to the north. But the job dragged and Father Esparragoza accepted a transfer. The new man at Nambé, Fray Juan José Llanos, revived the project, and in 1773, by hook or by crook, he saw it completed.

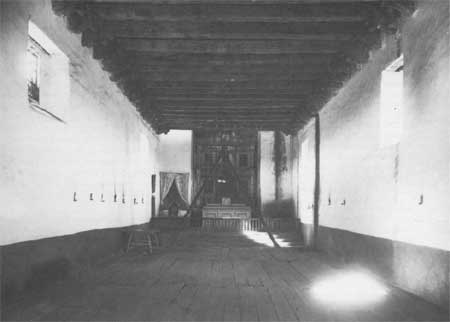

Despite its newness, Father Domínguez found nothing in the long spare church and its token two-room convento to praise. Judging from his notice of "carelessly wrought" and "badly laid" beams, he must have considered it a shoddy job. He was right. By 1804 it stood badly in need of repairs. Because the Ortiz family—the literate dñna Josefa Bustamante, her stepson and brother-in-law Antonio José Ortiz, and his brother Gaspar—owned most of the land in the Pojoaque area, don Antonio José took on yet another charity case. He paid for rebuilding the sanctuary and then had a new altar screen featuring Our Lady of Guadalupe made and installed. In July 1806, the month before Ortiz died, Fray Diego Martínez Ramírez de Arellano represented the Pojoaque church as "good and new." The convento, on the other hand, was "very deteriorated and most uncomfortable for the friars of this land." [2] Even smaller than Nambé, the pueblo of Pojoaque succumbed more rapidly to encroachment, intermarriage, and dispersal. Lieutenant Bourke, who took the trouble to visit the place in 1881, found only four families still living here.

Because the road between Santa Fe and Taos curved around the hill to avoid a steep grade, few travelers noticed the Pojoaque church. That probably saved it, at least for a time. Then, about 1906 or 1907, someone applied a pitched roof and schoolhouse cupola. No simple job, the roof comprised three sections: one covering the nave and running with the long axis of the church, another crosswise at the higher level over the sanctuary, and a third above the narrow apse. As late as 1915, Prince wrote of the Pojoaque church as "quaint and free from the vandalism of modern innovation." It possessed therefore "much more of interest to the intelligent and appreciative visitor than the most sumptuous structures of a recent day." Obviously he had not seen the new roof.

Today all that mark the historic church and pueblo of Pojoaque are low mounds and those telltale lines of vegetation that betray buried foundations. A mile or so away Roman Catholics in the area worship at the parish church of Our Lady of Guadalupe, a $160,000 modified A-frame, that sumptuous structure of a recent age. [4] Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||