|

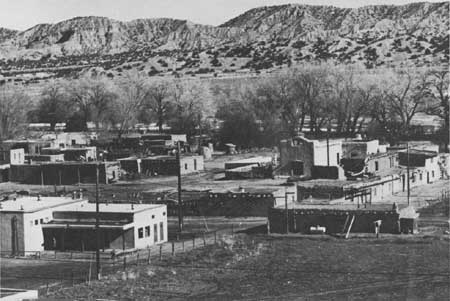

Tesuque In 1976 the Indians of Tesuque pueblo, as a courtesy, asked Archbishop Robert Fortune Sánchez for permission to level their Church and build a new one. The present one, which had a large weed growing out the bell gable in competition with the cross, was cramped and structurally infirm. In 1978 a calmer, more economical assessment prevailed. The old church was not so infirm after all, and it could be enlarged merely by extending the transept on the southeastern side. Thus it will be spared. Not as impressive as its predecessor, which looked to Father Domínguez in 1776 "like the great granary of an hacienda," rebuilt shorter in the 1880s, revamped several times since, the structure evidently occupies the same site and incorporates parts of the eighteenth-century foundations. [1] Ever since the settlement of Santa Fe in 1610, the nearby Tewa pueblo of Tesuque has been, for better or for worse, an annex of the capital. Reoccupied after the Pueblo Revolt and rechristened San Diego de Tesuque, it continued to supply labor to the governor's palace and to the Franciscan convento. A priest from Santa Fe administered the sacraments at Tesuque erratically. Often when the people of the villa had a celebration they prevailed on their closest Pueblo neighbors to take part. In biting cold and blowing snow on January 6, 1822, a crowd lined the Santa Fe plaza in blankets and buffalo robes to hail Mexican independence and to watch "a splendid dance by the Indians of the Pueblo of San Diego de Tesuque, which lasted until one in the afternoon." [2] In 1695, Fray José Díez, on loan to New Mexico from the Franciscan missionary college at Querétaro, superintended construction of Tesuque's first post-Revolt church. It survived the renewed uprising of 1696 because the majority of Tesuques, for their own good reasons, remained loyal to Diego de Vargas. Classed as small in 1706 and served by the missionary at Nambé, this church had deteriorated badly by 1745 when Fray Francisco de la Concepción González, a luckless Spaniard from Santander, had to rebuild it. The project did not go well. While serving as minister in Santa Fe, González had displeased the volatile Governor Gaspar Domingo de Mendoza and his associates. By accusing the Franciscan of complicity in the plot of a naturalized Frenchman to incite the Tesuque Indians, they sought his "total ruin, discredit, and expulsion." In 1744 Fray Francisco had gone to Mexico City to defend himself. He had won acquittal. Reassigned to Nambé late that year, he volunteered to minister to Tesuque as well. There his rebuilding of the church brought down on him the wrath of another governor.

The problem was labor. When Governor Joaquín Codallos y Rabal abused the Tesuque sernaneros, workers employed in Santa Fe on a weekly basis, denying them their pay and taking them away from catechism and labor on the Tesuque church, González protested. The governor fumed. To rid himself of the troublesome missionary he dredged up the old charge. That, however, did not stop Father González from finishing the church. Testifying in his defense in 1748, a co-worker described

The church that González built in 1745, the same one Domínguez inventoried in 1776, stood facing southwest on the Tesuque plaza for more than a century, apparently until the 1870s. The convento, abutting its southeastern wall, provided quarters for whoever came to say Mass. In 1796 it had, according to Fray Esteban Aumatell of Santa Fe, "a mirador, a stable and straw loft, a cloister, four rooms, kitchen, and pantry, one table, one chair with a bench, one lock." Twelve years later Father José Benito Pereyro considered both the church and convento "in good condition." The sacristy and baptistry had been repaired. Chaplain Francisco de Hozio of Santa Fe was looking after Tesuque in 1818 when Juan Bautista Guevara noted "an altar screen of painted boards which was made at the expense of the Indians of the pueblo." It was comparatively new, while the canvas of San Diego de Alcalá was the same one Domínguez had labeled "quite old" back in 1776. [4] By the time Lieutenants Bourke and Robert Temple Emmett rode out from Santa Fe in an ambulance, the old González church with its twin bell tower-buttresses, roofed balcony, and deep-set doorway, along with the convento, had slumped to ruin. The people were using as a substitute in 1881 "a sadly dilapidated one story flat roofed adobe structure, surmounted by a very small bell." Rumbling thunder convinced the two officers that they should opt for a tour of the kiva before the rains came. Bourke turned his back on Tesuque's undistinguished surrogate "church," practically the only pueblo church he did not sketch for his journal. He did like Tesuque though, composed as it was of

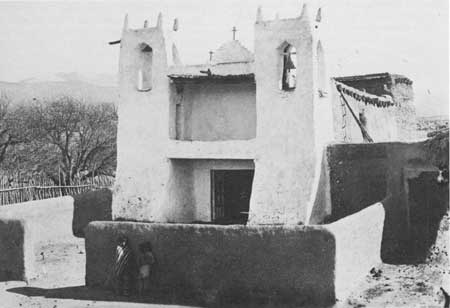

Later in the 1880s someone persuaded the Tesuques to rebuild their church. They cleared away the mounds of earth, used what they could of the old foundations, and, keeping the same width, reduced the length. The pueblo's resident population was smaller then, ninety-one in 1887, half as large as it had been in the 1740s. The rebuilding was as simple as could be: single nave, flat roof without transverse clerestory, plain slump-shouldered facade broken only by a Territorial-style door and a hole in the pediment for the bell, no towers or balcony, and about halfway back in each lateral wall, a large Territorial window. Ever since, this modest adobe church, somewhat altered after the Franciscans took over the cathedral parish in 1920, has lent its presence as a photographic backdrop to "colorful" Tesuque ceremonials, Victorian ladies, Model-T Fords, and Western movies. [6]

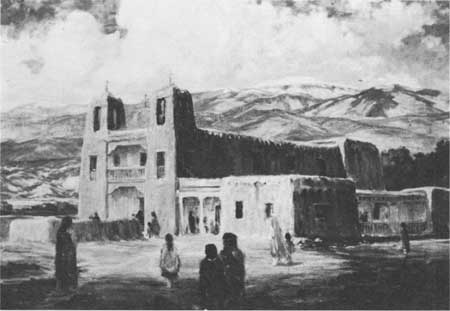

The mistaken notion that Tesuque once had a church that rivaled Ácoma's in scale and grandeur stems from a handsome if fanciful painting by Carlos Vierra. As a rule Vierra was not fanciful. A member of the Museum of New Mexico staff, he executed a series of some twenty mission paintings between 1912 and 1923. Where the churches yet stood he painted them "live." Where they had fallen he used the photographs of Adam Clark Vroman and others. In the case of Tesuque, Paul A. F. Walter explained in 1918, "Mr. Vierra measured and examined the site of the old building and from the 'viejos' (old men) of the pueblo obtained a detailed description of the church as it stood some sixty years ago. There is some resemblance to the Ácoma church and the south facade of the New Museum." [7]

It was a lovely painting. Domínguez, however, would not have recognized it as Tesuque.

Copyright © 1980 by the University of New Mexico Press. All rights reserved. Material from this edition published for the Cultural Properties Review Committee by the University of New Mexico Press may not be reproduced in any manner without the written consent of the author and the University of New Mexico Press. | ||||||||||

Top Top

|

| ||||||||||