|

Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park Chilkoot National Historic Trail Alaska |

|

NPS photo | |

When four people discover GOLD in the Klondike, thousands rush to Alaska to get rich. Their stories go far beyond GOLD. They can inspire us to wonder how far we would go to build the life we seek.

Wealth is out of reach for 98 percent of people living in the United States in the 1890s. They, struggle through poor working conditions, economic depressions, and unequal rights. But the 1896 discovery of Klondike GOLD promises instant wealth to those able to make a challenging journey.

The Klondike GOLD Rush brings together tens of thousands of people from over 30 nations including those who already call this place home. Many are here to find a better life. Others are sent to represent US interests This could be a golden opportunity, but what will happen....

. . . when new people overwhelm your home?

The Tlingit ("klin-kit") inhabited this region for thousands of years before the Klondike Gold Rush. Then, from August 1896 to July 1898, a wave of foreign gold-seekers inundated their lands. The newcomers crammed traditional Tlingit trade routes, like the Chilkoot Trail. They turned Dyea into a crowded and unhygienic boomtown.

Some Tlingit guides and packers profited by charging fees to carry the gear of stampeders—a nickname for the tens of thousands of people who came here seeking gold during the Klondike Gold Rush. Some Tlingit were cheated out of their profits. Others felt overpowered by the sudden frenzy. Their people faced violence, racism, and language barriers. Cultures clashed as their way of life went through tumultuous change.

. . . when society restricts your freedom?

The culture of Victorian America did not always let women step outside their domestic roles. Many late-1800s laws did not let women own property or be protected from discrimination and violence.

Some women came here during the Klondike Gold Rush with their husbands or families; others came on their own.

Some women were able to step out of their traditional roles here, and many triumphed on the journey. A few staked gold claims or ran businesses while others worked as stenographers or tourism promoters. For some, the last resort was prostitution.

During the Klondike Gold Rush, boomtown lawlessness increased all women's risk of murder, abuse, or trafficking. Risks were higher for African American, Alaska Native, and other minority women.

. . . when the community you serve excludes you?

Company L, Twenty-Fourth Infantry of the US Army was part of four African American regiments formed after the Civil War known as Buffalo Soldiers. From 1899 to 1902, Company L was stationed in Alaska during a US border dispute with Canada. They helped maintain law and order and protected the Tlingit from settlers' and miners' abuses. In July 1899, a swift forest fire in Dyea destroyed the dock, officers' cabins, barracks, and military storehouses. The unit then moved to Skagway, where it helped protect the town during a 1901 flood. Some soldiers brought their families here and participated in churches, sports, music groups, and civic events.

Despite some social integration, racism persisted. In 1900, thirty men from Company L joined the local YMCA, but many whites objected to a desegregated club, even though these men served the community. In 1902 Company L relocated to Fort Missoula in Montana.

One Event, Many Journeys

KEISH, also called Skookum Jim Mason, was a Tlingit and Tagish native of the Dakl'aweidi clan and a packer on the Chilkoot Trail. In 1886, he met American gold prospector GEORGE CARMACK in Dyea.

Carmack married SHAAW TLÁA (Kate), and had a daughter GRAPHIE. On August 16, 1896, with Keish and Kāa Goox (Dawson Charlie) they found gold that launched the Klondike Gold Rush.

Stampeder MABEL MEED lived in Dawson City from 1898 to 1907. Her husband's company built and operated the sternwheeler Prospector.

HARRIET PULLEN came to Skagway with $7. She went from pie-seller to profitable owner of properties and businesses in Dyea and Skagway. She was also a tourism promoter.

MARTIN ITJEN arrived during the Klondike Gold Rush and later promoted Skagway as a tourist destination. He helped preserve buildings, collections, and tales of the Klondike Gold Rush.

Entertainer GRACIE ROBINSON said she "worked hard for sixteen years in the States, and it was a hand-to-mouth struggle at best, while at dear Old Dawson, in a little over two years, I have made my fortune."

The Long Trek to the GOLD

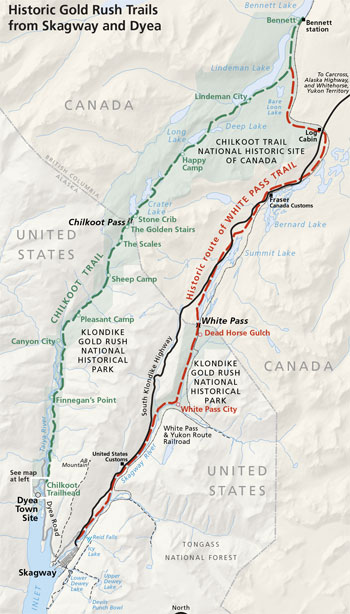

Word of the discovery spread worldwide. People began journeys north through Dyea and Skagway—the "Gateway to the Klondike." During the Klondike Gold Rush (August 1896-July 1898) the towns were ports for a mass migration that required a year's supply of food to cross into Canada. Stampeders hiked either the White Pass Trail or the Chilkoot Trail toward Dawson; if they went on to the Klondike gold fields, they faced a trip lasting months over land and water.

During the 1897-98 winter roughly 30,000 stampeders stayed in tents by frozen lakes, hundreds of miles from the gold fields, building rafts and boats and waiting. When the ice thawed, they paddled into raging rapids near Whitehorse that crushed some boats and even killed some travelers. Past the rapids, calmer waters carried them to Dawson City. Those who made it this far—nearly two years after the rush had begun—found all the gold claims staked out. The Klondike Gold Rush brought together thousands of people. Few found gold, but many shared in a remarkable journey. For the lure of gold many risked all, even their lives, to be part of it.

Discover the Klondike Gold Rush

How will you explore history, cultures, and nature at Alaska's most visited national park? You can tour historic town sites, hike "the world's longest museum" (the Chilkoot Trail), go camping, or photograph dramatic landscapes, seascapes, and wildlife.

Retrace the steps of the Klondike Gold Rush with these suggested itineraries. Please visit the park website for seasonal hours, programs, and reservation information.

START YOUR VISIT Begin at the park visitor center and museum for a film, information, exhibits, and ranger-led programs.

A FEW HOURS Attend a free ranger program. Explore outdoor exhibits. Earn your Junior Ranger badge at the family-friendly Junior Ranger Activity Center. Tour Jeff. Smiths Parlor Museum, Mascot Saloon Museum, and Moore Homestead.

A FULL DAY Visit the historic Dyea townsite (self-guiding). Hike the Chilkoot Trail.

OVER A DAY Camp or view wildlife in Dyea. Backpack on the Chilkoot Trail.

ALASKA AND BEYOND Explore Klondike Gold Rush International Historical Park. In the United States: Dyea and Chilkoot Trail, Skagway, White Pass, and Seattle. In Canada: Chilkoot Trail National Historic Site, Thirty Mile Heritage River (Yukon River), and Dawson Historic Complex National Historic Site.

Find History All Around You

Skagway's Historic District has a Klondike Gold Rush atmosphere full of preserved and restored buildings. Once a major gateway to the gold fields, Skagway and the White Pass valley have been designated the Skagway and White Pass District National Historic Landmark. Many of the buildings you find here contribute to the valley's national significance.

(click for larger map) |

White Pass & Yukon Route

Broadway Depot (1898)

VISITOR CENTER

The original train depot was used until the 1960s. Restored to 1908-15

appearance.

Martin Itjen House

(1901) BOOKSTORE

Martin Itjen owned this home with unique porthole windows. Restored to 1921-46

appearance.

Jeff. Smiths Parlor Museum

(1897) MUSEUM

A bank, Soapy Smith's base of operations, a fire department's garage, then a

museum. Restored to 1960s appearance.

AB Hall

(1900; non-NPS)

The Arctic Brotherhood Hall's facade has over 8,000 pieces of driftwood.

Restored to 1900 appearance.

The Mascot Saloon (1898)

MUSEUM

Skagway's longest-operating gold rush-era saloon. Closed by prohibition laws in

1916. Restored to 1905-16 appearance.

The Boss Bakery (1897)

TRAIL CENTER

The Boss Bakery supplied baked goods and candy during the Klondike Gold Rush.

Restored to 1902-06 appearance.

The Moore House (1897)

MUSEUM

Ben and Minnie Moore (born Klinget-sai-yet Shotridge) began building their

homestead in 1897. Restored to 1904-06 appearance.

Plan Your Visit

The park visitor center is at Broadway and 2nd Avenue in Skagway. Open daily (summer only). Park museum, film, and ranger-led programs. Contact the park for limited winter services.

For information about touring the historic Dyea townsite (self-guiding), visit the park visitor center. You must arrange your own transportation to and from Dyea.

The Chilkoot Trail was a trade route used by Tlingit people and is enjoyed by hikers today. To plan your hike, visit the park website and the Trail Center (summer only). Watch the required orientation video at the Trail Center before you hike. For overnight use, get a permit at the Trail Center or reserve in advance.

When traveling between the United States and Canada, you must report to customs. Canada customs in Fraser: www.cic.gc.ca. US customs in Skagway: www.uscis.gov.

We strive to make facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. Service animals are welcome. Call or check the park website for more information.

For firearms regulations check the park website. Federal law prohibits removing plants, animals, rocks, or other natural, cultural, or historic features from the park.

Emergencies call 911

Source: NPS Brochure (2020)

Once the major Klondike gateway, Skagway still boasts many historic gold rush buildings. Less evident now is how Dyea, nine miles north by unpaved road, rivaled it as Alaska's then largest town. Abandoned once the White Pass & Yukon Route Railroad was built, Dyea was eventually dismantled. In today's Skagway Historic District, private, city, state, and federal interests have cooperated to preserve or restore the late-1890s atmosphere. In summer, guided walking tours explore the town. Ask about these and other programs at the visitor center in the old railroad depot.

Visit the Skagway Museum and Gold Rush Cemetery, where old Skagway's crime boss Jefferson Randolph ("Soapy") Smith is buried. The 13,191-acre national historical park has National Park Service, city, state, and private lands. In 1998, Canada's Chilkoot Trail National Historic Site of Canada, Thirty Mile Heritage River (Yukon River), and Dawson Historic Complex National Historic Site, and the United States' Seattle, Skagway, Chilkoot Trail, and White Pass units, were designated as the Klondike Gold Rush International Historical Park.

Long Trail to the Klondike

GOLD! GOLD! GOLD! GOLD!

screamed headlines that sent over 100,000 people on a quest to pull themselves and the nation out of a three-year depression's economic ruin. But to strike it rich they would struggle against time, each other, and northern wilderness. US gold reserves plummeted in 1893. The stock market crashed. Ensuing panic left millions hungry, depressed, and destitute. Then came hope: on August 16, 1896, gold was discovered in northwestern Canada, near where the Klondike and Yukon rivers join. On July 17, 1897, the SS Portland reached Seattle with 68 rich miners and nearly two tons of gold! This promised adventure and quick wealth. For the lure of gold many risked all, even their lives, to be a part of the last grand adventure of its kind.

SEATTLE & BEYOND

The steamship Excelsior offloaded miners heavy with gold at San Francisco on the evening of July 14, 1897. The Portland docked at Seattle the morning of July 17, preceded by a reporter on a tugboat touting "more than a ton of solid gold on board." (In fact it was over two tons.) Among these first Klondikers were former Seattle YMCA Secretary Tom Lippy and his wife Salome. They ventured north on Tom's hunch in March 1896 just before the discovery. They brought back $80,000 and would eventually take nearly $2 million from the richest Klondike claim of all. The stampede was on, and all possible passage north to Alaska was booked.

Fewer than 3,000 took the all-water "rich man's route" from Seattle to St. Michael in Alaska, then up the Yukon to Dawson. It cost more than most stampeders could pay. Nearly 2,000 tried a difficult, all-land route from Edmonton. The handful who made It to Dawson took nearly two years, arriving after the rush was over. Most stampeders chose Chilkoot Pass or White Pass, and then floated down the Yukon.

DYEA & THE CHILKOOT TRAIL

Before the gold rush the Tlingit Nation controlled the strategic Chilkoot Pass trade route over the coast mountains to interior First Nation peoples' lands. The 33-mile Chilkoot Trail links tidewater Alaska to the Yukon River's Canadian headwaters—and a navigable route to the Klondike gold fields. Over 30,000 gold seekers toiled up its Golden Stairs, a hellish quarter-mile climb gaining 1,000 vertical feet, the last obstacle of the Chilkoot.

Most scaled the pass 20 to 40 times, shuttling their required ton of goods—a year's supply—north to the border for North West Mounted Police approval to enter Canada. No exact international boundary had been set, but Canada's regulation prevented starvation in the interior and protected its claim to all lands north of the passes. Conservationist John Muir was studying southeast Alaska glaciers when the stampede hit. Gold rush Dyea and Skagway "looked like anthills someone stirred with a stick," Muir wrote.

The Chilkoot Trail's fabled Golden Stairs humbled argonauts intent on the summit. This vivid image—an endless line of prospectors toting enormous loads like worker ants—became the Klondike Gold Rush icon. It took three months and 20 to 40 trips to carry their ton of goods over the pass.

SKAGWAY & WHITE PASS

A better port than Dyea, Skagway was the "Gateway to the Klondike." Wild, it had something for all. Confidence artists and thieves, led by Jefferson Randolph "Soapy" Smith, and greedy merchants lightened the unwary stampeder's load. Up-to-date Skagway had electric lights and telephones. It boasted 80 saloons, three breweries, many brothels, and other service or supply businesses.

The White Pass Trail was 10 miles longer—but its summit less steep and 600 feet lower—than the Chilkoot Trail. Two months' overuse destroyed it. Its second life began as British investors started to build the White Pass and Yukon Route Railroad in May 1898. Rails reached the White Pass summit in February 1899, Bennett Lake in July 1899, and Whitehorse in July 1900. With the railroad open, development at Dyea and along the trails ceased. But by then the rush was over.

Chiefs Doniwak and Isaac of the Tlingit were pivotal in transmountain packing and trading as gold prospecting increased in Canada's interior. As the Klondike stampede intensified, demand for Native packers exceeded supply. Pack horses, aerial tramways, and other schemes would soon reduce the Tlingit's packing business.

Falsely dubbed "all-weather," the White Pass Trail—boulder fields, sharp rocks, and bogs—earned the name Dead Horse Trail. Over the 1897-98 winter 3,000 horses died on it "like mosguitoes in the first frost," Jack London wrote.

At the Chilkoot and White pass summits, Canada's Mounties gave properly outfitted stampeders official entry into Canada. "It didn't matter which one you took," said a stampeder who had traveled both trails, "you'd wished you had taken the other."

YUKON VIA BENNETT LAKE

It took three months just to cross the mountains to the interior. Then most of the 30,000 stampeders sat out the 1897-98 winter in tents by frozen lakes Lindeman, Bennett, or Tagish—still 550 miles from the gold fields. They built 7,124 boats from whipsawn green lumber and waited for lake ice to melt. Finally, on May 29, 1898, the motley flotilla set out. In the next few days five men died, and raging rapids near Whitehorse crushed 150 boats. After the rapids it was a long, relatively easy trip, but bugs and 22-hour sunlit days drove boaters nearly mad. Near Dawson some feuding parties split up—cutting in half even their boats and trypans. Then, finally, Dawson City!

Whipsawing trees into planks, stampeders built boats or rafts—and then waited for a long Arctic winter to end.

A hundred miles of lakes led into the Yukon River, where canyon rapids soon gave way to smooth water beyond Whitehorse.

DAWSON CITY & THE GOLD FIELDS

(click for larger map) |

Before the gold rush a few Han First Nations people camped on the small island where the Yukon and Klondike rivers join. Prospecting in the area George Washington Carmack, Keish ("Skookum Jim" Mason), and Kaa Goox (Dawson Charlie) struck gold on August 16, 1896, on Rabbit (later re-named Bonanza) Creek. On August 17 they filed claims in Fortymile, the nearest town, 50 miles downriver. This sparked the first stampede as prospectors already in the interior got the news via the informal bush communication network. Former Fortymile trader and grubstaker Joseph Ladue shrewdly platted Dawson City and made a fortune selling lots.

Dawson City boomed. Soon it was Canada's largest city west of Winnipeg and north of Vancouver, its population 30,000 to 40,000. It stretched for two miles by the Yukon, bulging with goldseekers. Anything desired could be had—for a price: one fresh egg $5, one onion $2, whiskey $40 a gallon. However, most stampeders did not reach Dawson City until late June 1898, nearly two years after the big discovery, and prospectors already in the region had long since staked claim to the known gold fields. Many disillusioned stampeders simply sold their gear and supplies for steamboat fare to the outside, their visions of wealth washed away. Canadian historian Pierre Berton writes that many stampeders arrived in Dawson City and simply wandered about, utterly disoriented by its frantic activity, not bothering to prospect at all. Played out over such vast space and time, the adventure itself seems to have been, for many people, the biggest attraction of the Klondike Gold Rush. Mining was another story.

To get through the perennially frozen soil called permafrost, miners built fires to melt a shaft down to where the gold lay. Two men digging like this for a winter used 30 cords of firewood that they had to cut themselves (until the stampede's large labor pool arrived). Miners dug shafts down to the gold just above bedrock, deep below the layers of frozen muck and gravel. At bedrock, they tunneled out, "drifting," as it was called, along the gold-bearing gravels of the old stream course. Dirt and gold-bearing gravel, called "pay gravel," were hoisted out of the hole and piled separately for sluicing (washing away the dirt and gravel) in spring and summer, once sunlight thawed the dumps and streams. Reporting from right on the scene, journalist Tappan Adney wrote that—considering the cost of reaching the country and the cost of working the mines—"The Klondike is not a poor man's country."

Women and a few children joined the stampede. Many women who went north were spouses, mining partners, or business owners. Some prostitutes, styled as "actresses," went north to ply their trade.

In Dawson City and Seattle more fortunes were made off miners than by mining. By 1906 Klondike gold exceeded $108 million at $16 per ounce.

Plan Your Visit

From Skagway and Dyea, stampeders started across the coastal mountains to Yukon River headwaters en route to Dawson City, Canada, and the gold fields. To learn more, visit the park museum, watch a film, and attend ranger led programs at the park visitor center, Broadway and 2nd Ave., Skagway, open daily (summer only). To explore the Dyea town site, obtain a self-guiding brochure at the visitor center. Visitors must provide their own transportation to and from Dyea.

Hike the 33-mile Chilkoot Trail (permit required for overnight use) starting in Dyea to realize challenges gold seekers faced. Visit the park website to plan your hike. Also check at the Trail Center in Skagway. Watch the Chilkoot Trail hiking video at the visitor center. You must be well-prepared. Get A Hiker's Guide to the Chilkoot Trail from Alaska Geographic, www.alaskageographic.org.

The White Pass Trail has disappeared in most places. Do not attempt it.

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. Call or check our website. Service animals welcome. For firearms regulations check our website.

If you travel between Canada and the United States you must report to customs. Contact Canadian customs in Fraser: www.cic.gc.ca, and US customs in Skagway: www.uscis.gov.

Federal law prohibits removing plants, animals, rocks, or other natural, cultural, or historic features.

Source: NPS Brochure (2016)

Documents

2009 Bat Inventory: Pilot Study, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/AKR/NRDS—2013/520 (Dashiell Feierabend and Dave Schirokauer, August 2013)

2009 Amphibian Monitoring Report: Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2014/626 (Heather Wetherbee, February 2014)

2010 Amphibian Monitoring Report: Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2014/627 (Shelby Surdyk, February 2014)

2014 Amphibian Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2015/784 (Mallory St. Pierre, April 2015)

2014 Bird Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2015/785 (Mallory St. Pierre, April 2015)

A Wild Discouraging Mess: A History of the White Pass Unit of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Julie Johnson, 2003)

Acoustic Bat Monitoring in Alaska National Parks 2016-2018 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/AKRO/NRR-2020/2096 (Paul A. Burger, March 2020)

Alaska and the Klondike Gold Fields (A.C. Harris, 1897)

Amphibian Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2015 Summary NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR-2018/1655 (Shelby L. Surdyk and Jami Belt, May 2018)

Amphibian Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2016 Summary NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR-2018/1589 (Shelby Surdyk and Stacie Evans, February 2018)

Amphibian Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2017 Summary NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR-2018/1587 (Shelby Surdyk and Andrew Waldo, February 2018)

Amphibian Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2018 Summary (Andres Santini Laabes and Jami Belt, November 2023)

Archaeological Investigations in Skagway, Alaska

1. The White Pass and Yukon Route Broadway Depot and General Office Buildings, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Catherine H. Blee, September 1983)

2. The Moore Cabin and House, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Catherine Holder Blee, 1988)

3. The Mill Creek Dump and the Peniel Mission, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Diane Lee Rhodes, September 1988)

4. Father Turnell's Trash Pit, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska (Catherine Holder Spude, Douglas D. Scott and Frank Norris, August 1993)

5. Additional Investigations at the Mill Creek Dump and the Peniel Mission, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska (Ray Depuydt [and others], 1997)

6. Residential Life on Block 39 (Doreen C. Cooper, 1998)

7. Block 37, Lot 1, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska (Carl Späth, Kurt P. Schweigert and Robin O. Mills, 2000)

8. A Century at the Moore/Kirmse House (Doreen C. Cooper, 2001)

9. Excavations at the Pantheon Saloon Complex (Tim. A. Kardatzke, 2002)

10. The Mascot Saloon (Catherine Holder Spude, 2006)

Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2006/349 (Eran Hood, Ginny Eckert, Sonia Nagorski and Carrie Talus, March 2006)

Beneath the Surface: Thirty Years of Historical Archeology in Skagway, Alaska (Becky M. Saleeby, 2011)

Bird Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2015 Summary NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR—2017/1442 (Shelby L. Surdyk, May 2017)

Bird Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2016 Summary NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR-2018/1590 (Shelby Surdyk and Stacie Evans, February 2018)

Bird Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2020-2022 Summary (Bethany Humphrey and C.E. Furbish, October 2023)

Bird Surveys at Klondike Gold Rush NHP: 2023 Summary (Jeffrey Bodendorf and C.E. Furbish, November 2023)

Chilkoot Trail: From Dyea to Summit with the '98 Stampeders Occasional Paper No. 26 (Robert L. Spude, ©Cooperative Studies Unit University of Alaska, 1980)

Climate Change and Archaeological Resources, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: Cultural Resource Brief (Draft, September 26, 2016)

Climate Change in Northern Southeast Alaska, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (September 25, 2009)

Climate Change Scenario Planning for Southeast Alaska Parks: Glacier Bay, Klondike, Sitka, and Wrangell-St. Elias NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/AKSO/NRR—2014/831 (Robert Winfree, Bud Rice, John Morris, Don Callaway, Don Weeks, Jeff Mow, Nancy Fresco and Lena Krutikov, July 2014)

Design of Nelson Slough Wetland Restoration Project (Steamcraft, October 2003)

Documenting Over a Century of Natural Resource Change with Repeat Photography in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR-2015/1017 (Ronald D. Karpilo, Jr. and Sarah C. Venator, September 2015)

Dyea Area Plan and Environmental Assessment (September 2014)

Ecological Inventory of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park and Adjacent National Forest Lands U.S. Forest Service R10-TP-48 (S.J. Paustian, S.J. Trull, R.A. Foster, N.D. Atwood, B.J. Krieckhaus and J.R. Rickers, September 1994)

Ethnographic Overview and Assessment, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park Final Report (Thomas F. Thornton, August 2004)

Ezra Meeker's Quest for Klondike Gold (Howard Clifford, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 12 No. 2, Summer 1995; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Fire Management Plan Environmental Assessment, Alaska Region Coastal Park Units (June 2024)

Foundation Statement, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska/Washington (April 2009)

Foundation Document Overview, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska (March 2016)

General Management Plan, Development Concept Plan and Environmental Impact Statement, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (September 1996)

Geologic Map of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (July 2022)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report: Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2022/2426 (Amanda Lanik, July 2022)

Glittering Prospect: The Alask Gold Rush Reconsidered (Robert E. Ficken, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 21 No. 2, Summer 2007; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Hikers on the Chilkoot Trail: A Descriptive Report (Peter Womble, Wendy Wolf and Donald R. Field, January 1978)

Historic Research Plan: Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Karl Gurcke, April 28, 2011)

Historic Structure Report: Jeff. Smiths Parlor Museum, Skagway and White Pass District National Historic Landmark, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Skagway, Alaska (Robert Lyon, ed., May 2010)

Historic Structure Report: Patterson-McDermott Cabin (Kathleen Wackrow, 2018)

Historic Structure Reports for Ten Buildings: Administrative, Physical History and Analysis Sections, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Catherine H. Blee, Robert L. Spude and Paul C. Cloyd, January 1984)

Historic Transportation Resources in Skagway and Dyea (Kristina Hill, April 2005)

Invasive and Exotic Species Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park

Invasive plant management for Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2010 Summary repor NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2011/131 (Kassie Hauser, January 2011)

Invasive and Exotic Species Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2011 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2011/224 (Zachary Goodrich, December 2011)

Invasive and Exotic Species Management for Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2012 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2013/431 (Peter Frank, January 2013)

Invasive and Exotic Plant Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park: 2013 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2014/640 (David Golden, April 2014)

Invasive and Exotic Plant Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2014 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/KLGO/NRDS—2014/742 (Ramsey Mauldin, December 2014)

Invasive and Exotic Plant Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2015 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR—2016/1120 (Kevin Hauser, January 2016)

Invasive and Exotic Plant Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2016 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR—2016/1343 (Kylie Mosher, December 2016)

Invasive and Exotic Plant Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2017 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR—2018/1612 (Devon McCabe Burton, March 2018)

Invasive and Exotic Plant Management in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: 2018 Summary Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR—2018/1821 (Laura Gould, November 2018)

Inventory of Cultural Resources in The Chilkoot and White Pass Units of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park University of Washington Reconnaissance Report No. 40 (Caroline D. Carley, 1981)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (2017; for reference purposes only)

Kathleen Eloisa Rockwell: Belle of Dawson, Queen of the Yukon, Flower of the North (James Bledsoe, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 12 No. 4, Winter 1998-99; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Klondike Literature: The Mad Rush for Truth in the Frozen North (Terrence M. Cole, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 22 No. 2, Summer 2008; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Klondike: The Chicago Record's Book for Gold Seekers (1897)

Klondike: The Chicago Record's Book for Gold Seekers (1897)

Legacy of the Gold Rush: An Administrative History of the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (HTML edition) (Frank B. Norris, 1996)

Lichen-Air Quality Pilot Study for Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park and the City of Skagway, Alaska (C.E. Furbish, Linda Geiser and Claudia Rector, December 2000)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (December 2005)

Long-term Vegetation Change in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR-2017/1408 (Lindsey Flagstad and Tina Boucher, March 2017)

Moore Homestead Interpretive Kitchen Garden Project (Daniel Winterbottom w/Alison Blake and Kari Stiles, November 21, 2005)

Moore House Exhibit Designs, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (1994)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Canyon City State Cabin (Susannah Dowds, February 11, 2019)

Chilkoot Trail (Mile 0 to Canadian Border) (C.M. Brown, March 15, 1973)

Chilkoot Trail and Dyea (Frank Norris, August 1, 1987)

Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (Frank Norris, June 1990)

Sheep Camp State Cabin (Susannah Dowds, February 11, 2018)

Skagway and White Pass District (Frank Norris, Terrence Cole and Bonnie Houston, July 1987, April 1989, March 1998)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRR-2011/288 (Barry Drazkowski, Andrew Robertson and Greta Bernatz, January 2011)

Nelson Slough Wetland Restoration Implementation Plan (Meg Hahr and Kevin Noon, January 2004)

One Man's Adventure in the Klondike (Terrence Cole, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 11 No. 4, Winter 1997-98; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Park Newspaper (The Stampeder): 2001 • 2002

Proposed Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park: Historic Resource Study (Edwin C. Bearss, November 15, 1970)

Research to Support Visitor Management at Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park (University of Vermont, Date Unknown)

Risky Business: Banking During the Alaska Gold Rush (Elmer Rasmuson and Terrence Cole, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 12 No. 3, Fall 1998; ©Washington State Historical Society)

Skagway, District of Alaska, 1884-1912: Building the Gateway to the Klondike — Historical and Preservation Data on the Skagway Historic District (HTML edition) University of Alaska, Fairbanks Cooperative Studies Unit Occasional Paper No. 36 (Robert L.S. Spude, 1983)

Soil Survey and Ecological Site Inventory of Skagway-Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska (Dennis Mulligan, 2015)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2010 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SEAN/NRTR—2012/547 (Christopher J. Sergeant, William F. Johnson and Brendan J. Moynahan, February 2012)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2011 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SEAN/NRTR—2012/561 (Christopher J. Sergeant, William F. Johnson and Brendan J. Moynahan, March 2012)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2012 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SEAN/NRTR—2013/706 (Christopher J. Sergeant and William F. Johnson, March 2013)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2013 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/SEAN/NRTR—2014/840 (Christopher J. Sergeant and William F. Johnson, January 2014)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2014 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SEAN/NRR—2015/927 (Christopher J. Sergeant and William F. Johnson, February 2015)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2015 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SEAN/NRR—2016/1131 (Christopher J. Sergeant and William F. Johnson, February 2016)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2016 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SEAN/NRR—2017/1383 (Christopher J. Sergeant, William F. Johnson, February 2017)

Southeast Alaska Network Freshwater Water Quality Monitoring Program: 2017 Annual Report NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SEAN/NRDS—2018/1144 (Christopher J. Sergeant, William F. Johnson, January 2018)

State of the Park Report, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Alaska State of the Park Series No. 5 (April 2013)

The Klondike Official Guide (Wm. Ogilvie, Department of the Interior, 1898)

The Klondike Stampede (Tappan Adney, 1900)

The Story of the Bishop Rowe Hospital in Skagway, Alaska (Isabel M. Emberley, 2nd ed., 1905)

The White Pass Route (W.D. MacBride, extract from The Beaver, Outfit 285, September 1954)

Vegetation Change in Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/KLGO/NRR—2017/1408 (Lindsey Flagstad and Tina Boucher, March 2017)

Visitor Experiences and Visitor Use Levels at the Dyea Area of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park NPS Technical Report NPS/PWR/UW/NRTR-2006-01 (Mark E. Vande Kamp and Erin Seekamp, November 2005)

Words of Gold: Reporters Bring the World News of the Klondike Stampede (J. Kingston Pierce, extract from Columbia: The Magazine of Northwest History, Vol. 12 No. 1, Spring 1998; ©Washington State Historical Society)

klgo/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025