|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 8:

Changing Stories: Interpretation

|

There are no outstanding natural, historic,

archeological, or other features deemed sufficiently important to

attract visitors. However, the features that do exist are of sufficient

note that their proper and adequate "interpretation" will make the

visitors' stay much more interesting and meaningful.

-- CODA, "Statement for Interpretation type document," 1957 [1] |

The National Park Service has long considered basic interpretation of a park's natural and cultural resources an essential tool for enhancing public enjoyment of the park. The agency also believes that when visitors understand an area's resources through good interpretation, they are more likely to be concerned about protecting those resources. Until the early 1960s, however, the only interpretation available to visitors in the Lake Roosevelt area was that provided by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) at Grand Coulee Dam with only minimal input from Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO) personnel.

From the 1960s until the 1980s, much of the interpretation provided by LARO naturalists and rangers focused on recreational skills. When Interpretive Specialist Dan Brown arrived in 1988, the interpretive program was "not really all that well developed." He recalled that the park was "treated kind of like an urban recreation area — kite flying," with classes in skills such as paddling canoes and snorkeling. The focus of interpretation at Fort Spokane was on the military period only, leaving out many other important aspects of the site. Former Superintendent Gerry Tays agrees that interpretive efforts were "not getting their fair treatment." [2] The interpretive program at LARO has changed greatly since then.

Interpretation by the U.S. Bureau of

Reclamation

Americans and foreigners alike are fascinated by the story of Grand Coulee Dam. Since the 1930s, publicity has made it truly larger than life. Reclamation, having already experienced the public's great interest in the construction of Boulder Dam, built a grandstand for visitors to view the construction activity at Grand Coulee Dam. In 1936, two parking lots and vista points, one on each side of the Columbia River, provided vantage points of the construction, and eloquent guides lectured on the art and science of dam building. A construction model and a hydraulic model of the dam were displayed. Several hundred thousand people came to the site each year, and Reclamation made them feel welcome. From then until today, the emphasis of interpretation at the dam is upon the engineering achievements that the dam represents. For example, a 1998 Reclamation handout at the Visitor Arrival Center proclaims, "The creation of Grand Coulee Dam is a story of developing and using equipment of gigantic proportions, breaking records, taking risks and reaching unique and innovative solutions to build a giant among dams." [3]

|

The public provided a seemingly insatiable

appetite for statistics about "the eight wonders of the world." People

loved to hear how many pancakes the 3,000 to 6,000 workers ate each

morning at breakfast or how many miles of tubes ran through the dam.

They devoured pictures of the great structure, as high as a

forty-six-story building, just five feet shorter than the Washington

Monument, and they saw drawings of the 12.5 million barrels of concrete

or envisioned them together in a train 500 miles long. Most popular

were comparisons with the Great Pyramid of Egypt, or two, or three, or

even four of them.

-- Paul Pitzer, Grand Coulee, 1994 [4] |

In 1941, Reclamation began planning a museum to interpret the construction and purposes of Grand Coulee Dam. The agency offered space in the facility to the National Park Service for natural history exhibits and an office. Under the first interbureau agreement for managing Lake Roosevelt, signed that year, Reclamation agreed to provide guides and lecture services at the dam and to coordinate that activity with related services established elsewhere by the Park Service. This was reaffirmed in the 1946 Tri-Party Agreement. [5]

World War II curtailed tourism at the dam, however. Beginning in 1941, federal guards protected the dam day and night from sabotage, theft, and military attack. Fences blocked entry at both ends of the dam, and boats patrolled the waters of Lake Roosevelt. After the war ended, Reclamation built a tourist railroad (flatcars pulled by an engine) that carried tourists from the west vista house to the powerhouse to see the generators and then back to the west vista house. In 1950, Reclamation transferred the Crown Point site, which has marvelous views of the dam and of Lake Roosevelt, to the State Parks and Recreation Commission, with the understanding that any development of the site would be coordinated with the Park Service. [6]

Claude Greider, LARO's first superintendent, encouraged Reclamation guides to mention the Park Service and the national recreation area in their talks. He even provided several draft paragraphs outlining the recreational development the Park Service hoped to achieve along Lake Roosevelt. Frank Banks, Reclamation District Manager, felt that the lecturers should provide information in their own words, but he did approve one sentence stating that the reservoir was under the jurisdiction of the Park Service. Perhaps this rather uncooperative attitude of Reclamation was responsible for Greider's feeling that the Park Service interpretive program should be "completely independent" of Reclamation. [7]

|

I have the feeling that the National Park

Service interpretive program should be centered upon the recreational

area and that all lectures and interpretive devices around and in the

vicinity of the Dam should be left to the Bureau of Reclamation. There

appears no way to integrate the different procedures practiced. A

distinct personality is to be expected from our presentation and it can

only be achieved out in the field area assigned for administration to

the Service. . . . The story of the Coulee Dam had best be left to the

builders.

-- John E. Doerr, Park Service Chief Naturalist, 1949 [8] |

To encourage visitors to stay overnight, Reclamation created a very popular thirty-minute display of colored lights playing on the water spilling over the face of the dam. The seasonal light show began in 1957, the same year Reclamation opened its new tour center. These developments led LARO Superintendent Hugh Peyton to anticipate increased visitation to the national recreation area's facilities at Spring Canyon and North Marina. Although the tour center focused on telling the story of the construction of Grand Coulee Dam, Reclamation did invite LARO to provide a large map of the national recreation area (NRA) for the lobby and one or two photographs for a slide show. When LARO personnel requested Park Service help with this project, however, they were told to wait until the Western Museum Laboratory (where exhibit specialists were located) was in operation. The work was done in 1960, with detailed directions provided by LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson, who asked that visitor facilities be shown by symbols and activities by cartoon characters. Although visitors had no trouble finding the Reclamation tour center, they had more difficulty finding Park Service facilities along the lake because of the lack of signs on approach roads. [9]

In 1961, Reclamation replaced its guided tours of the powerhouse with a free self-guided tour of the powerhouse and later of the pumping plant, too, with taped talks at a number of locations. During the 1960s, the Reclamation tour center was staffed jointly by Reclamation and the Park Service. LARO Park Naturalist Paul McCrary wrote, "The interests of the Bureau of Reclamation and the Service at [Coulee Dam] go hand-in-glove. It is undesirable and impractical for the Service to establish separate visitor center facilities." During this period, up to four hundred people an hour entered the tour center. The Park Service evening programs there brought together North Marina and Spring Canyon campers and people staying in local motels, providing an opportunity for LARO personnel to emphasize the recreational opportunities of the area. But by 1967, Park Naturalist Arthur Hathaway was suggesting that these duties at the dam revert to Reclamation. [10]

The construction of the third powerhouse at Grand Coulee Dam required Reclamation to reconsider its visitor facilities. In 1967, Reclamation contracted with Spokane architect Kenneth Brooks to design ways to showcase Grand Coulee Dam. His proposal included an Arrival Center on the left bank below the left powerhouse, an exterior elevator from the top of the forebay dam to the third powerhouse, and an aerial cable car to an exhibit center high above the river that would interpret geology and human history. Most of these elaborate ideas never made it into reality. [11]

The third powerhouse construction required that the 1957 tour center be removed in 1968, and a temporary visitor center was constructed with advice from LARO Superintendent Howard Chapman. The bust of Franklin D. Roosevelt that had been dedicated in 1953 also had to be removed because of the construction. It was relocated in 1974 from the site of the forebay of the third powerhouse on the east end of the dam to its present site on the left bank just upstream of the dam. The Spokane World's Fair of 1974 led to very high visitation; over 468,000 people came to the dam that year. [12]

|

| Slide show being given inside Reclamation's Visitor Arrival Center, 1962. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

Ever since the 1940s, LARO staff had been urging Reclamation to provide more information to dam visitors on the recreational facilities along Lake Roosevelt. During the planning for the existing Reclamation Visitor Arrival Center (VAC), which opened in 1981, the Park Service expected to have significant input in exhibit planning. LARO staff proposed producing a joint film that would describe both the dam tours and other recreational activities. LARO hoped to be able to provide "short, but pleasant and light" exhibits in the new facility, along with a publication sales outlet and evening programs. [13] LARO's suggestions were not always adopted, however. When LARO Superintendent William Dunmire reviewed the exhibit plan for the new VAC, he wrote, "I am astonished to find no focus on Coulee Dam National Recreation Area in this plan other than as a minor element of the CRT units [television or computer screens]. . . . I had discussed the desirability of having an orientation sequence to recreational opportunities on Lake Roosevelt a year or so ago with Bob Evans and understood that it would be incorporated in the plan." [14]

The spillway colored lighting program was discontinued in 1977 because the new powerhouse required more water for power generation (spilling water over the face of the dam thus became wasteful). The light show was replaced by lectures and movies sponsored by the Park Service and Reclamation. Because of public demand, in 1989 Congress authorized a laser light show to be played across the face of the dam, a program that requires much less water to be spilled. The show runs every night from May until September. The laser light show uses popular music and a human voice speaking as the Columbia River to provide a thumbnail history of the river and the people who have lived along it and used its waters. Although it does mention recreation as a benefit of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project, the only reservoir it mentions by name is Banks Lake; Lake Roosevelt and the NRA are not specifically mentioned. [15]

Even though the planning documents written in the 1970s and 1980s called for the Park Service to partner with Reclamation, this did not happen until the early 1990s. LARO staff felt that the 1981 VAC did not lend itself to much more than dispensing park brochures and program schedules and providing recreational information at computer stations. Often even these methods of getting out the word about LARO failed, such as when the computer printers were down or the folders had all been handed out. The new 1990 Multi-Party Agreement, however, mentioned that interpretation at the Reclamation VAC should address the impact of the Columbia Basin Irrigation Project on the tribes and also should inform visitors of available recreational resources. Chief of Interpretation Dan Brown approached Reclamation officials with a proposal based partly on the interpretation program at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, where the Park Service, not Reclamation, led interpretive tours through the dam's powerhouse. According to Brown, Reclamation was reluctant to have LARO personnel share the same information desk because "our uniforms were more official looking and they felt that visitors would come to us rather than to them, and they were right." [16] Personnel of both agencies shared the same information desk in 1990 and 1991, but then the Park Service was relegated to a small desk that was not easily visible, so less than 10 percent of the nearly 500,000 annual visitors stopped at it. [17]

LARO had had an agreement with Reclamation that a blind vendor would sell LARO books at the VAC; these sales contributed significantly to the park's total sales. (Blind vendors, by law, are given priority rights to provide concession services in appropriate federal buildings). When LARO personnel began staffing the VAC, Reclamation relocated the vendor to a trailer in the parking lot because the vendor was not willing to share the inside space with the Park Service. The State Department of Services for the Blind contended that the Northwest Interpretive Association (LARO's cooperating association) was a vending facility in direct competition with the displaced visually impaired vendor and should be prohibited from selling books. Dan Brown and others were called to Seattle in 1995 to testify regarding the case. An arbitration board decided in favor of the blind vendor, and the Park Service had to move out of the VAC. If the Park Service continued to sell publications in the VAC, the agency would have to give a percentage of sales to the blind vendor. The Park Service decided not to continue its presence and sales items there. Brown summarized, "We essentially just closed up shop and went home. It was a four-year challenge." He felt that it was difficult to make a strong case for the Park Service without more support from within the agency, from Reclamation, and from the cooperating association. Today, the blind vendor in the VAC sells a few LARO items; he buys them from the Northwest Interpretive Association and sets his own prices. [18]

Current LARO Superintendent Vaughn Baker does not plan to have Park Service interpretive personnel work at the VAC. "Frankly, I wouldn't want to be there," he said. "The purpose of the VAC is to tell the story of the dam, and that's not why we're here. That's Reclamation's story; that's not our story." Currently the only Park Service "presence" in the Reclamation facility is a large map of the national recreation area. Present interpretive staff remains interested in helping Reclamation "flesh out their story," but whether this will occur remains to be seen. [19]

Interpretive Staffing at LARO

LARO did not have any personnel who specialized in interpretation until the early 1960s. Although LARO and Regional Office staff did some interpretive planning during the 1940s and 1950s, no interpretive services were provided at all until 1962. The Mission 66 program provided the funding to create interpretive facilities and hire small staff. In 1962, two ranger naturalists were hired, and soon the program moved from planning and development into administration of services. In November 1977, the Interpretation & Resource Management structure was converted into two new operating divisions: Visitor Protection and Resource Management, and Interpretation and Visitor Services. In 1978, the first year LARO had a separate Division of Interpretation, District Rangers and Technicians worked 25 percent of their time in interpretation. Seasonals worked in interpretation most of the time but also had other duties. [20]

LARO's interpretive program through the 1980s accounted for less than 10 percent of the park's staff time and only 5 to 7 percent of the park's base funding. Between 1977 and 1991, LARO interpretive staffing ranged from one to nearly three permanent positions and up to nearly three seasonals. This fell well below the minimum level of interpretive services, which was considered to be two permanent staff and almost four seasonals. Seasonal interpreters were brought on late and were not ready to present programs until early July, well after the visitor season had begun. In some years, interpretive programs had to be cancelled at particular campgrounds, and the Fort Spokane Visitor Center could not be kept open seven days a week. [21]

Dan Brown was hired in 1988 as LARO's Interpretive Specialist. In approximately 1990, a separate Division of Interpretation was again created (evidently the earlier division had been merged back with visitor protection and resource management in the 1980s). This gave the Interpretive Specialist direct-line authority to manage the NRA's interpretive program and a seat at the park's management table. Cultural resource management responsibilities were removed from the Interpretive Specialist position in 1992. The interpretive division at that time had little funding; of the park's seventy-two full-time equivalents in 1989, interpretation accounted for only three positions. When Gerry Tays was hired as LARO Superintendent in 1993, Park Service Regional Director Charles Odegaard asked him to elevate the role of interpretation in the park. Meanwhile, Brown continued to emphasize the inadequacy of staffing and funding for the program in the early 1990s. The division oversaw visitor centers (separated by some ninety miles), five cooperating association sales outlets, six amphitheaters, a living history program, community outreach, wayside exhibits at nine locations, a park publications program, and the museum collection. Funding for a South District interpreter was provided in 1991. Brown deliberately closed down the interpretive programming at Kettle Falls in an effort to force park management to provide funds for a North District interpreter. This position was, in fact, funded in 1995. Brown also took money out of the interpretive program budget that was needed for seasonals in order to hire an education technician, knowing the park would eventually provide the money to bring on seasonals for interpretation. [22]

Brown recognized that managers of particular programs within the park had an interest in protecting their own programs:

We had some extremely sharp individuals for division chiefs while I was there. They were very, very aggressive and were very good at building their own programs. They saw interpretation's growth as challenging resources that could come to their programs. They didn't mind if interpretation grew, as long as it didn't take money away from their program. [23]

Through the 1990s, the interpretive program continued to rely heavily on volunteers and interns. Congress established the Volunteers-in-Parks program in 1970 to augment the visitor experience. At LARO, as at other parks, the volunteers have mostly been involved with the interpretive program. The jobs of these volunteers, some of them experts in particular fields, have included staffing information desks, administering children's programs, assisting with archaeological excavations, working in resource management, working on museum-related projects, performing living history, and serving as Interpretive Hosts at campgrounds. An employee of the National Air and Space Museum started an innovative nationwide program known as "sky talks." He arranged for volunteer astronomers to give talks in national parks, and in 1974 he began a program to train Park Service personnel to give these programs. Sky talks were given at LARO in 1973 and 1974 and perhaps other years as part of this initiative. The number of volunteers each season ranged from less than five to fifty (the latter was in 1985), and their cost per hour to the park was quite low. [24]

Another program that has provided volunteers to the interpretive division of LARO is the Student Conservation Association, founded in 1957. The program funds college or high school students who work in national parks in various capacities. For a number of years, LARO has had one or several Student Conservation Association volunteers who provide interpretive services during the visitor season. [25]

Significance of LARO — What to

Interpret?

The 1941 draft agreement between Reclamation, National Park Service, and Office of Indian Affairs assigned the Park Service the responsibility of establishing a museum at LARO. The question of the primary interpretive themes for the recreation area has been debated and refined by the Park Service ever since. In 1941, Mount Rainier Park Naturalist Howard Stagner and Senior Archeologist Jesse Nusbaum spent a couple of days at Lake Roosevelt surveying the "values" of the area. The Park Service Supervisor of Interpretation felt that the main story was geology and that archaeology or history would play a minor role. Stagner suggested that all the interpretive work be administered by one agency (Park Service or Reclamation), including the engineering and reclamation story and natural history, to ensure fair emphasis and effective coordination. Park Service Regional Geologist J. Volney Lewis also emphasized the geology of the area as a primary theme and recommended that the Park Service and Washington state cooperate in a roadside exhibit at Dry Falls State Park. [26]

The 1944 Development Outline and the 1948 Master Plan for LARO also emphasized the geology and natural history of the area and downplayed the historical values. In 1949, Regional Naturalist Dorr Yeager prepared a Preliminary Interpretive Development Outline for LARO. His report focused on the geological and biological values and mentioned as secondary the need for historical exhibits on the "romantic history of the Columbia River as a route for early day travel." He felt that visitors to Kettle Falls would be the most receptive to interpretation and recommended focusing efforts there, with a small museum and conducted nature walks. [27]

During the 1940s and 1950s, Regional Office personnel and the LARO Superintendent researched the history of the upper Columbia River. Aubrey Neasham, Regional Historian, prepared a brief history of LARO in the late 1940s that covered its pre-dam history. In the early 1960s, LARO began preparing resource study proposals for archaeological site surveys and for a more detailed and site-specific history of the Lake Roosevelt area that would help in interpreting the recreation area to visitors. [28]

Two late 1950s documents, the 1957 Statement for Interpretation and the 1958 Museum Prospectus for LARO, addressed the question of interpretive themes once again. The first report emphasized the Grand Coulee as the foremost natural feature to interpret; historical features included Fort Colvile, Fort Spokane, American Indian leaders, pictographs, and Kettle Falls. The second report made specific recommendations about which visitor centers would address which topics: Fort Spokane — history, geology, ethnology, and biology; Kettle Falls — history, ethnology, and biology; and North Marina — geology and desert flora. [29]

By the early 1960s, when LARO had its own interpretive staff, the emphasis of interpretation was on water recreation, with history and natural history as secondary. The 1964 Master Plan for LARO included the goal of providing "informational and interpretive programs primarily oriented to enjoyment of available recreational resources." By 1971, however, water recreation was being given equal weight with human history and natural history in the recreation area's interpretive program. [30]

LARO staff prepared an Interpretive Prospectus for the NRA in 1975. This document mentioned several interpretive themes: establishing National Park Service identity as separate from Reclamation; water recreation; story of the Columbia River; and story of the formation of the reservoir and its effect on the people around it. The prospectus contained some new ideas, including restoring buildings at Bossburg and interpreting the mining history of the area. The geologic story of the Grand Coulee would not be told because it was already being covered at Dry Falls. Interpreters would focus on subjects in the area where the program was being held. Interpretation would show "how the hand of man in modern times has shaped and controlled this region's landscape and how recreation opportunities were made possible by creation of the lake impoundment." By the early 1990s, LARO had added a new, broad theme to those of recreation and human and natural history: the Ice Age Floods and how the recreation area's geologic features relate to that far-reaching series of events. [32]

|

Interpretive theme for LARO:

"To interpret the recreational resources and related activities as a means of increasing visitor enjoyment. Secondary themes including history (particularly at Fort Spokane), archeology, and natural history are appropriate and desirable for those visitors wishing mental stimulation as well as physical recreation." -- National Park Service, A Master Plan for Coulee Dam National Recreation Area, 1968 [31] |

The nation's bicentennial in 1976 led the Park Service to direct LARO and all other Park Service units to incorporate special Bicentennial activities into their interpretive programs. LARO did so. Other new, rather specialized themes being emphasized nationwide at this time that also affected LARO's programming included energy conservation, resource preservation, cultural minorities, and environmental education. Many of LARO's programs were aimed at increasing recreational visitor safety, often through hands-on instruction in boating, water skiing, sailing, canoeing, and snorkeling. These skills-oriented programs, along with arts and crafts and games, were replaced by 1993 with guided canoe trips and additional environmental education activities. At the same time, campfire programs changed from showing Walt Disney and Marx Brothers films and cartoons to ranger-developed programs on various park resources. One new interpretive effort focused on the park's peregrine falcon reintroduction program. [33]

Contractors completed LARO's Historic Resource Study in 1980. This report suggested quite a few historic sites within the NRA, both above and below the water, that could be interpreted to the public. These sites included Chinese placer mining sites, Hunters Landing, the John Rickey homestead, Klaxta townsite, Seaton ferry, Old Detillion Bridge, Bossburg, flooded communities, and the Hawk Creek orchards and railway grade. Some, but not many, of these sites and topics have been interpreted over the years. For example, North District staff have given gold-panning demonstrations and talked about the history of mining in the area. [34]

The 1998 Draft General Management Plan for LARO outlined several primary and secondary interpretive themes for the NRA: the transition zone between the desert-like Columbia Basin to the south and the slightly wetter Okanogan highlands to the north; river economies, traditional land use, archaeological research, and geo-archaeology studies; the continuing cultural heritage of today's tribes; the fur trade; Fort Spokane; and the dam and reservoir. It also established an "historic and interpretive management area" for LARO that encompassed Fort Spokane and designated sites in the Kettle Falls area. [35]

In the early 1990s, the Park Service changed its interpretive planning process. The Interpretive Prospectus, which dealt with the media portion of interpretation, was combined with the Statement for Interpretation, which covered personal services, to form a document known as the Interpretive Plan, which is currently being prepared. The draft document notes that fewer than 5 percent of LARO's visitors attended interpretive programs. In the recent General Management Plan, the interpretive themes revolve around the NRA's geology, natural history, cultural history, and recreation opportunities. [36]

|

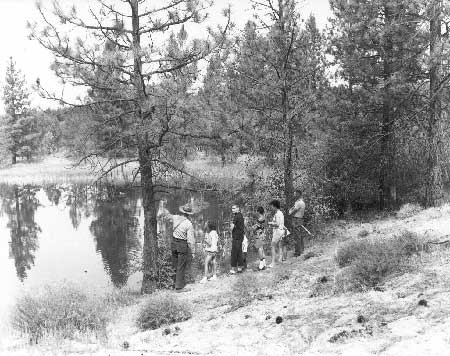

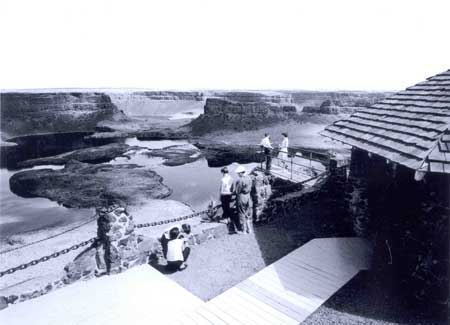

| Ranger-led nature walk at Kettle Falls, 1963. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

Interpretive Facilities

The Park Service museum program did not receive much funding until the Mission 66 years. The Museum Branch located in Washington, D.C., produced many exhibit plans for western units of the National Park System between 1956 and 1966, and this helped justify the reestablishment of the Western Museum Laboratory in San Francisco in 1957.

Mission 66 planners called the buildings that housed these exhibits "visitor centers" rather than "museums" to reflect their dual functions of providing both visitor orientation and area information at lobby information desks and traditional exhibits. Most of the exhibits used a narrative approach, with exhibits arranged to illustrate a series of related ideas. [37]

|

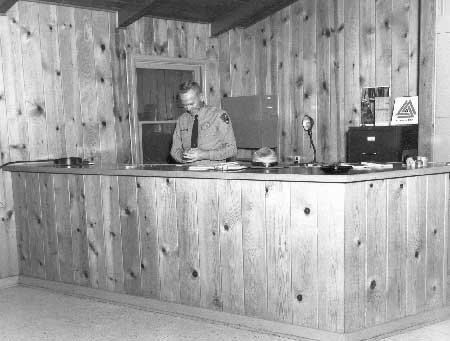

| Information desk at Kettle Falls Ranger Station, 1967. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

LARO's staff of the 1950s had a quite modest vision of interpretive facilities needed at the recreation area. In fact, the Chief of the Division of Interpretation on the national level recommended disapproval of LARO's Mission 66 prospectus because its proposed facilities and staffing were so inadequate. The proposal called for one naturalist and one ranger-naturalist through 1966, with no funding budgeted for self-guided trails, wayside exhibits, interpretive signs, or campfire circles. These deficiencies were corrected in the 1957 Statement for Interpretation. [38]

Mission 66 funded visitor centers, visitor-activated audiovisual devices, and amphitheaters and campfire circles Servicewide. The three visitor centers proposed for construction at LARO under Mission 66 were at Fort Spokane (also the proposed site of park headquarters at this time), North Marina, and Kettle Falls. In general, each was to interpret resources best suited to its locality, with little overlaps among the three and no overlap with Reclamation exhibits at the dam. Each would have orientation and information exhibits in a lobby with additional interpretive exhibits elsewhere. Topics covered would include geology, natural history, human history, the national park idea, and boating safety. The stories would be presented through audiovisual programs and static exhibits. The planners believed that most visitor contacts would be made in the visitor centers and through wayside exhibits rather than through naturalist programs. [39]

The 1964 Interpretive Prospectus for LARO benefited from the lessons learned from operating the area's interpretive program for three visitor seasons. It recommended that the visitor centers have changing exhibits to attract repeat visitors. Campfire programs and conducted walks, wayside exhibits at boat launch ramps and along highways, and off-site programs about the recreation area were also recommended. [40]

By 1968, LARO's interpretive program was mostly centered at Fort Spokane and Kettle Falls. At Fort Spokane, audiovisual programs were supplemented by tours of selected historic buildings and a self-guided trail. Both areas had campfire circles, as did Porcupine Bay and Evans, and more were proposed. The district information stations served as both staff offices and as visitor contact stations, providing area and local information, publications for sale, first aid, law enforcement, fee collection, and interpretive services. [41]

LARO's interpretive facilities included six amphitheaters in 1989. Four of these were soon upgraded with new enclosed projection booths, control panels, column speakers, and improved lighting systems. They seated 60 to 175 people. A 1990s interpretive facilities project created the Kettle Falls Visitor Contact Station in 1995, which housed the North District Interpreter and LARO Archeologist. [42]

Beginning in approximately 1970, the LARO Superintendent supervised personnel at the Park Service's Spokane field office, which was established to support Park Service participation in Spokane's Expo 74. The personnel based there, generally two employees, provided information about various national parks; conducted outreach interpretive activities in the Spokane area; worked with local outdoor recreation groups; worked with the local news media; and presented teacher workshops. Instead of being phased out after the Expo, in 1975 the Park Service field office in Spokane was combined with that of the U.S. Forest Service. In 1977, the joint information office moved to the lobby of Spokane's federal courthouse building in order to provide better public access. Because of Park Service studies of its field offices Servicewide, the Spokane office was closed in early 1982, although the Forest Service continued to respond to requests for information on Park Service units. [43]

|

Park Headquarters serves some visitor contact

function in Coulee Dam, for those who stumble across it. Indeed, on

entering the village from the main highway, one finds two signs on the

same pole, one with an arrow toward "Visitor Information" (a local

operation) and another sign directing a traveler to "National Park

Service" in a different direction. The distinction is the more

mystifying in that access to either is handy by the same route.

-- Harpers Ferry Center, "Draft Interpretive Prospectus, Coulee Dam National Recreation Area," 1993 [44] |

In 1968, LARO's Master Plan mentioned that a joint-agency visitor contact station near Kettle Falls would be a convenient place for visitors to learn about the NRA, and this was noted again in the park's 1975 Interpretive Prospectus. Prompted by the imminent opening of the North Cascades Highway and Spokane Expo 74, LARO and Colville National Forest personnel began planning for a multi-agency visitor center located where Highway 395 crossed Lake Roosevelt in the Kettle Falls area. By 1993, the Park Service, Bonneville Power Administration, Reclamation, and Washington Department of Wildlife were also involved in the project. Agency personnel obtained a design for the building and almost $375,000 in funding, and LARO interpretive personnel drafted the exhibit text and designed some of the interior facilities. Park Service and Forest Service personnel were slated to staff the building during the summers, although some at LARO saw the project as a potential drain to park resources. The facility, known as the Sherman Pass Interagency Visitor Center, was scheduled to open in 1995. The project "died a slow, painful death" in 1995, however, because of the lack of a formal cooperative agreement for leasing the land from the Washington Department of Wildlife. Neither the Forest Service nor the Park Service had the time or energy to pick up the ball and bring the project back to life. LARO staff are willing to partner again, but not to take the lead to revive the project. [45]

Interpretive Programs

LARO's first Statement for Interpretation, prepared in 1957, declared that "the interpretive program must be taken to the visitor." [46] LARO personnel of the 1950s recommended several types of naturalist programs to serve visitors to the recreation area. These included conducted boat trips, auto caravans to pictographs and geological formations, and evening campfire programs. The first interpretive services were provided in 1962. The 1964 Interpretive Prospectus for LARO emphasized campfire programs as the basic tool for interpretation, supplemented by conducted walks and boat trips. Daytime programs such as naturalist walks, however, had low attendance. Evening programs were more popular, but the Park Naturalist emphasized that visitors were tired by evening and the programs needed to be entertaining, relaxing, enthusiastic, and no longer than forty-five minutes. The 1964 plans called for campfire circles at Fort Spokane, Porcupine Bay, and Evans campgrounds to supplement the amphitheater already in use at Kettle Falls. [47]

When a formal interpretation program began at LARO in 1962, it emphasized personal contact. This worked relatively well when funding allowed and when the visitation was not too high. Personal contact programs in the 1970s included evening campfire programs, nature and history walks (some specifically for children), historic building tours, living history, guided canoe trips at Kettle Falls, and visitor center and informal contacts by LARO staff, VIPs, and tribal members. Interpretation was a hard sell to many recreationists, and LARO staff had to be inventive in encouraging people to come to programs. Topics of programs during the 1970s included wildlife, plants, geology, fire safety, astronomy, insects, history, energy conservation, and recreation. The ever-popular living history program at Fort Spokane began in 1973. According to a 1981 report, about 15 percent of LARO's summer visitors attended interpretive programs. Because most visitors were repeat visitors who came on weekends, most programs were given on weekend evenings, and films provided variety. [48]

|

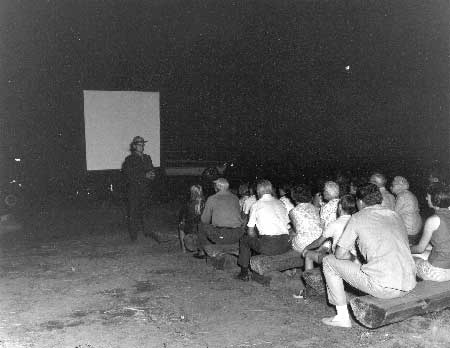

| Program being given at Fort Spokane amphitheater, 1968. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

The interpretive program of the 1980s was much the same, with continued emphasis on water recreation and safety and on living history. Guest interpreters presented a number of special programs, including popular clinics on fishing for walleye. The annual Old Fashioned Community Christmas at Coulee Dam, sponsored by LARO, was instituted in 1985. Another new and popular program was weekly guided canoe trips on Crescent Bay Lake. LARO personnel found that roving through campgrounds and day-use areas an hour before an interpretive program greatly increased attendance. The assumption that more diverse programs were needed to serve repeat visitors was called into question by a 1990 survey that found that only 12.8 percent of visitors had decided not to attend a program because they had seen it before. [49]

|

The recreational programs of basket weaving,

building sandcastles, scuba diving lessons and showing Disney films,

have been replaced with programs that interpret the cultural and natural

resources of the park. The small-type, text-only information sheets

have been replaced with NPS format site bulletins with attractive

graphics and layout. . . . The foundation is now in place for a strong

interpretive program.

-- CODA, "Operations Evaluation Executive Summary," 1994-1995 [50] |

A survey of LARO visitors was done in 1990 to document the existing situation and make recommendations to management to improve attendance at interpretive programs. The consultant noted that interpretive desires of visitors to recreation areas differed from those visiting traditional national parks, noting that many have said that a national recreation area is "just a place to get wet." The survey found that although visitor preferences tended to vary with location, wildlife was the favorite topic. Recommendations included emphasizing different subjects at different locations, offering evening programs between 8 and 9 p.m., and making more effort to let people know about programs through improved bulletin boards, newsletters, and program flyers. Program attendance did increase in 1991, even though programs decreased by one-third, probably because LARO implemented the recommendations of the 1990 study. A popular new children's program was initiated in 1991 to teach children how to fish. Because almost one-quarter of LARO visitors were children, children's programming was expanded to include the new Junior Ranger program. Recreational skills demonstrations were greatly de-emphasized in 1993 and were replaced with additional environmental education activities. [51]

|

| Members of Spokane Tribe of Indians dancing at Fort Spokane for a cultural demonstration program, ca. 1971. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3165). |

|

Today, if one visits the Coulee Dam

Recreational Areas that are administered by the NPS or the Bureau of

Reclamations' Visitor Center at Coulee Dam, there is a void of

information, exhibits, and displays to the visitor to enlighten him that

there is a Colville Indian Reservation not only boarding [sic] the

Coulee Dam project but Indian resources are an integral part of the

total project. The rich culture and history of the Colvilles' [sic] is

inundated with information and recordings of how much concrete is in the

dam, kilowatt production, increased revenues to the government, the rich

flow of electrical power and water away from the Reservation to the

large urban areas and the rich farming areas of the Columbia Basin,

respectively. The visitor is then given the opportunity to visit and

utilize one of the many neat, clean, recreation areas within the Coulee

Dam Project area administered by the NPS. These oasis's [sic] of clean

cut grass, picnic tables, barbeque areas, overnight facilities,

electricity, running water and picturesque picnic sites are naked to any

sensitivity or recognition of the Colville Culture, History and

Tradition that formerly occupied these beautiful historical Indian areas

on the Columbia River.

-- George M. Davis, Superintendent, Colville Agency, 1986 [55] |

LARO reports from the 1940s through the 1960s sometimes mentioned the importance of interpreting American Indian use of the Columbia River, often focusing on the pre-contact era. LARO's first Statement for Interpretation suggested that local tribal members could set up displays and give talks on Indian villages in the area, fishing at Kettle Falls, and other topics. In 1971, LARO received funding from the Regional Office to promote cultural demonstrations, and members of the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT) and Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI) put on programs at several campgrounds that were well received. LARO's operating budget financed a number of cultural programs, but soon the Mount Rainier Natural History Association (LARO's cooperating association was an affiliate of this group) began to fund the programs. Art Hathaway, LARO's Assistant Chief, Interpretation and Resource Management, set up the cultural demonstrations with the tribes. He stated that the purpose of these programs was to inform visitors about local and other tribes and their cultures. CCT tribal member and LARO seasonal ranger Howard "Doodle" Stewart made contacts with many tribal members and arranged for these programs. One program featured a CCT woman beading the Park Service arrowhead symbol. Other programs, however, consisted of dancing, drumming, chanting, stories and legends, leather crafts, art, and tepee raising. The tribal participants also sold food and craft items. These special programs were presented only 1971-1973; they were discontinued after Hathaway transferred to the Spokane field office in 1974. [52]

In keeping with a 1973 Park Service directive to show greater sensitivity to cultural diversity in interpretation, LARO's 1980 General Management Plan stated that the park would support programs concerning American Indians whose lives were closely associated with the recreation area and its general vicinity. Besides the 1970s cultural demonstrations mentioned above, another such program, starting in 1980, invited Indian artists to interpret the park. A 1981 LARO document, however, reported only limited interest in joint tribal/Park Service program development. In 1987, the Park Service made an official commitment to respect and actively promote tribal cultures as a component of the parks themselves. Under this policy, Park Service personnel were urged to actively consult with American Indians on interpretive programs relating to particular tribes, develop cooperative programs with tribes, and provide for presentation of tribal perspectives of their lifeways and resources. [53]

In 1990, LARO began bringing in guest speakers from the CCT to present campfire programs on local Indian culture. LARO's 1993 Statement for Interpretation specifically mentioned that the park would pursue hiring a tribal member through the Job Training Partnership Act to present craft demonstrations, staff the Visitor Arrival Center information desk, and provide information on tribal culture and the Reservation Zone of Lake Roosevelt. The 1998 Draft General Management Plan also stated that the park would try to improve the blend of all themes, including stories of the aboriginal inhabitants of the area. Two examples of these efforts are American Indian cultural programs at Spring Canyon and the 1999 exhibit at Fort Spokane on the Indian Boarding School era. Experts in subjects such as Indian history and culture currently provide specialized training for park interpretive staff. [54]

Meanwhile, since the 1970s the CCT and the STI have worked to establish tribal museums of their own. The Colville Tribal Museum and Gift Shop opened by 1991 in the town of Coulee Dam, and the Spokanes opened a museum in Wellpinit in approximately 1975 (this is no longer operating). [56]

Wayside Exhibits and Interpretive

Trails

Wayside exhibits along highways or at campgrounds and boat launch ramps are important at LARO because visitors often go directly to recreation sites, bypassing visitor contact stations. LARO's Mission 66 prospectus mentioned that a number of observation points with roadside exhibits would be developed along Lake Roosevelt to supplement the information available at the proposed visitor centers (this fit in with the overall Mission 66 program Servicewide). The 1958 Museum Prospectus listed twelve interpretive sites, mostly along heavily traveled roads. By 1964, LARO personnel saw the value of providing safety and other information to visitors at launch ramps, and they proposed exhibit shelters at North Marina and at Fort Spokane. They also recommended signs to interpret the geology, natural history, history, and ecology of the area. [57]

By 1975, much of this work was still in the planning stages. The Interpretive Prospectus of that year talked about the need for visually identifiable wayside exhibits in various locations, including ones at launch ramps "where we want to hit water users with a punchy safety message." In the late 1970s, LARO signed a contract with Harpers Ferry Center for eighteen wayside exhibits for the Fort Spokane grounds and the six major launch ramps. The exhibits at the ramps were kiosks with three main panels plus side panels. By 1985 these panels were fading, and they were replaced in 1987. The new panels included a map of LARO on each central panel plus information on boat safety inspections, personal flotation devices, and emergency phone numbers. [58]

LARO embarked on a park-wide bulletin board plan in 1990. Park personnel used cyclic funding to replace exposed plywood bulletin boards with boards with locking Lexan doors, cork backing, and standardized layouts. The total number of existing bulletin boards was sixty-four. The plan called for bulletin boards at each boat ramp, campground fee payment station, restroom building, and concession facility in the NRA. [59]

LARO has a few short trails, most serving interpretive rather than purely transportation purposes. Self-guided trails within the recreation area were considered in the 1950s for the Fort Spokane, Spring Canyon, Kettle Falls, and North Marina areas. District Ranger Don Carney established the Bunchgrass Prairie Nature Trail at Spring Canyon in 1974 and wrote a trail booklet about the plants and geology of the area. The trails at Kettle Falls and Fort Spokane were developed in 1979 with information on local history along both trails. The wayside exhibits for the trail at St. Paul's Mission were installed in 1984. [60]

In 1980, the NRA's six trails totaled less than four miles in length. These consisted of Bunchgrass Prairie Nature Trail, Lava Bluff Trail, Fort Spokane Interpretive Trail, Fort Spokane Campground Trail, Kettle Falls Interpretive Trail, and St. Paul's Mission Trail. Former South District Interpreter Lynne Brougher notes, "We want to go beyond these. . . high visitor-use areas. There's a lot of history to be told out there." The park currently has plans to add more wayside exhibits in several new areas such as Hawk Creek. These would include interpretive messages on geology and local history. [61]

Publications

Little written information was available for early visitors to LARO. In 1957, the park offered a mimeographed information sheet and a map prepared by the Roosevelt Lake Log Owners Association that listed visitor facilities, but an official Park Service map and guide to the area had not yet been created. A boater's guide was prepared in the 1960s, and a free fourteen-page Park Service booklet was available by 1964. The early 1970s version of the boating guide provided safety information, a guide to specific locations and features, and information on geology, launch ramp locations, navigation lights, inundated towns, and customs inspections. In 1975, park staff prepared a folder on fish and fishing at Lake Roosevelt patterned after a Glacier National Park brochure. By this time the NRA had an official Park Service folder. Harpers Ferry Center developed a two-color folder for LARO in 1970. A four-color folder replaced this in 1984, emphasizing water recreation opportunities within the recreation area. [62]

LARO also contracted for historical publications on the area. Researcher David Chance prepared a booklet in the late 1970s on the military period of Fort Spokane, published by the Pacific Northwest National Parks Association. In 1975, park staff produced four free leaflets on Fort Colvile, St. Paul's Mission, Kettle Falls, and Fort Spokane; these were all revised in 1980. These handouts were upgraded to site bulletins in 1992, and site bulletins on Grand Coulee Dam and on the Laser Light Show were written in cooperation with Reclamation that year. [63]

LARO began publishing The Lake Roosevelt Mirror, its visitors' guide in newspaper form, in 1979, and it has been published most years since then. Until 1983, the Pacific Northwest National Parks and Forests Association printed the newspaper, and concession operations have also provided some funds. Then, because of a Servicewide policy change, the newspaper was no longer a special project and had to be funded by a percentage of the sales revenues generated at park sales outlets. LARO's percentage obtained in this way did not equal the costs of the newspaper until 1986. [64]

Fort Spokane

Use and Acquisition of Fort Spokane

|

The interpretive program at Fort Spokane is closely connected to the story of the loss of most of the buildings from the military period, the acquisition of the land by the Park Service, and the subsequent restoration/rehabilitation work on buildings, foundations, and landscaping. Restoration and interpretation of the extant buildings and foundations at Fort Spokane has been a concern of the park since it acquired the former military reservation in 1960.

Park Service efforts to research the history of Fort Spokane began in 1958, when Regional Historian John Hussey prepared a five-page history of the fort's military period. Research picked up in 1960. Hussey conducted more studies of the fort, and an architect and student crew prepared measured drawings. LARO staff began talking to area residents, trying to gather information and artifacts. The Regional Office and the LARO Superintendent arranged for researchers to copy documents and historic photographs in local newspaper files and the National Archives. [65]

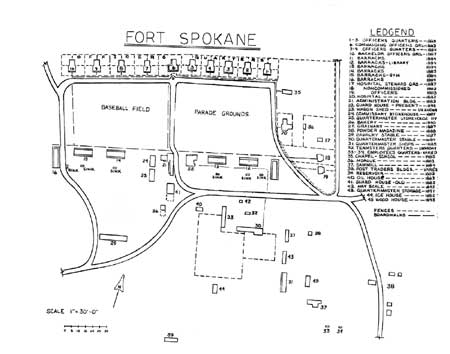

The 331 acres of land at Fort Spokane on the upper bench were transferred to the Park Service on May 9, 1960, by Public Land Order 2087. Of the forty-five original buildings at Fort Spokane, five remained standing on the site — the guardhouse, quartermaster stable, powder magazine, reservoir house, and quartermaster storehouse. Twenty historic foundations were also evident in the 1960s. Preservation of these buildings and foundations began in 1961. [66]

|

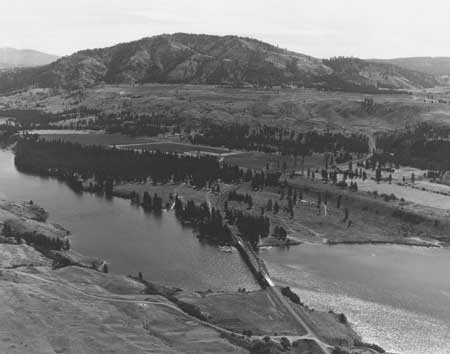

| Looking across Spokane Arm to site of Fort Spokane, 1958. The LARO campground and swim beach are on the lower bench near the bridge, and the historic grounds and buildings are on the bench to the right of the road. Photo courtesy of Grant County Historical Society and Museum, BOR Collection (P222-116-40762). |

Interpretion at the Fort Spokane Guardhouse

The focus of interpretation of Fort Spokane through the 1960s was on its military period. Other uses — Indian Agency, Indian boarding school, and Indian hospital — were mentioned in the discussion of interpretive programs and planning but not emphasized. For example, in 1968 LARO Superintendent David Richie suggested the following themes for the guardhouse exhibit room: why Fort Spokane was established; garrison life of the soldier; social life of the soldier; "family"; and the abandonment of the fort (including its early 1900s roles). By 1975, interpreters were increasingly emphasizing the post-military period, but the re-creation of the grounds continued to depict the 1890s development. [67]

|

| Information desk at Fort Spokane guardhouse, 1967. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

Interpretation at the fort, like many other aspects of LARO's development, reflected the personal commitment of park staff and their spouses. For example, in the early 1960s LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson carved and his wife Sis painted twelve-inch-tall wooden soldiers, based on historic photographs, for display in the guardhouse. [68]

During the 1980s and 1990s, LARO and other Park Service personnel recognized the need to improve the interpretation of Fort Spokane. The 1997 Museum Management Plan suggested less emphasis on interpreting the guardhouse as a detention facility, questioned the effectiveness of the mountain howitzer display (a reproduction donated in the mid-1980s), and commented that the stable interpretation did not convey the importance of animals to the military. An exhibit installed in 1999 in the guardhouse acknowledged the suffering and the cultural damage caused by the Indian boarding school at Fort Spokane. Its nine panels are based on interviews with tribal elders, telling the story from the tribal point of view. One panel makes effective use of the location by mentioning that children who ran away from the school were held in solitary confinement in the guardhouse for several days. [69]

|

To me the overriding story was not the

military, baseball, etc. The story was the interaction between the

American Indians living there and this other culture that came in, and

the resulting interaction over time, with Fort Spokane as the key

player.

-- Dan Brown, LARO Interpretive Specialist/Chief of Interpretation 1988-1995 [70] |

A recurring debate at Fort Spokane, as at many historic sites around the country, is whether to target a specific time period or to try to give a feeling of the site through its several phases. There is currently a "big push" within the Park Service, according to LARO Education Specialist Lynne Brougher, to strive for multiple-view, multiple-culture interpretation. The days of interpreting Fort Spokane only as a short-lived military facility appear to be over. [71]

A local teacher, Ralph Brown, began working at Fort Spokane as a seasonal historian in 1964. He led walking tours of the fort grounds; he also tried to identify Fort Spokane objects in private collections. LARO had hoped to hire a permanent historian, but the Park Service during this period began to assign research projects to historians in Washington and Denver and have the historians in the field focus on interpretation; communications skills thus took precedence over discipline specialty. Although everyone involved felt that the basic story would best be conveyed through audio-visuals, an exhibit room and furnished jail cell were seen as important components. Nevertheless, as the Park Service Acting Chief, Division of Interpretation and Visitor Services, wrote about Fort Spokane, "personal service . . . is our hallmark. The others are tools which should be used when they are best suited to the particular communications job at hand." [72]

The exhibits prepared in the late 1960s for the Fort Spokane guardhouse were rather sparse. As was true Servicewide, a variety of media, particularly audiovisual and publications, was used instead of narrative description to tell much of the story. In 1968, a few donated historic objects were on display, along with historic photographs from the National Archives and a framed document from the Indian school period. At first, there was not enough funding for life-size dioramas, so LARO recommended displaying military gear and civilian objects to complement the audiovisual program and programs presented by the information-receptionist. A slide cabinet provided programs on Grand Coulee Dam, Lake Roosevelt, and national parks of the northwest. The proposed research on furnishings was postponed. Within a few years, however, a diorama with two mannequins was installed in one of the prison cells. This portrays a sergeant of the guard seated at a table filling out a report, with an orderly reporting to him. In the accompanying audio, which runs continuously, the sergeant of the guard explains his duties. Beginning in 1975, another cell housed the sound-slide program and prints showing uniforms of the period. Soon, a second diorama showed a prisoner in the solitary cell. The two dioramas are still in place. [73]

LARO opened the Fort Spokane grounds to visitors in a limited way in 1962. At that time, the individual buildings were still surrounded by chain-link fences. That summer, about two thousand visitors came per month. When the visitor center opened in the guardhouse in 1966, local chambers of commerce sponsored an open house. LARO kept the visitor center open every day of the year, with summer hours from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. Soon, scheduled guided walks on the human and natural history of the area were available. The visitor center guardhouse was last staffed year-round in 1985. [74]

|

IMAGINE Take a moment and imagine yourself as a small child taken from your family. You have no idea of where you are going, what will happen when you get there, or most of all — what you did to deserve this. Strange people you have never met are telling you things in a language you do not understand. In a matter of hours everything about your young life is torn away and you are left in a room with several other children trying to figure out what is expected of you in this strange place. The place was Fort Spokane Indian Boarding School. Soon you would stand on the parade ground where soldiers once stood. Your world is about to change in a way that would affect you the rest of your life and the lives of the generations to follow. -- Panel 1, 1999 Fort Spokane exhibit text [50] |

The script for the original slide program at Fort Spokane was produced locally in 1965. In 1968, Harpers Ferry Center produced a new program, making only minor changes to the earlier script. This script heavily emphasized the military history of the fort. The text was revised in 1981 to include more information on the boarding school and hospital. The audio stations in the guardhouse use an interview format modeled after the once-popular television program, "You Are There." For example, an Irish man's voice explains to visitors that he was incarcerated in the guardhouse cell for disorderly conduct. [75]

A popular tool that began to be used at Fort Spokane in 1969 was a timed recording of period bugle calls and a retreat parade, similar to those already in use at Fort Davis National Historic Site, Texas. These recordings played every half hour from 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., and they could be heard as far away as the campground. The sound quality was very poor, however, and in 1984 the Regional Audiovisual Specialist moved the broadcasting equipment from a tree to the cupola of the guardhouse. The slide-sound system in the guardhouse also did not always work well; sometimes sounds from this system invaded the taped bugle calls or were heard over area telephones. Park staff are now installing new equipment sent from Harpers Ferry Center to replace the old eight-track players. [76]

Until 1977, rangers used the baker's table inside the powder magazine at Fort Spokane for demonstrations of loading cartridges. Exhibits in the magazine, located far from the guardhouses, tended to be vandalized, however. In the quartermaster stable, visitors can wander past stalls that once housed fifty-eight mules, many with the names of their long-gone occupants still posted above the stalls. [77]

Landscaping and Roads, Fort Spokane

|

The old Fort grounds were cleaned of all

debris, old fences, brush and many trees that had encroached on the

grounds since military occupation. Approximately 14 acres of land along

officers' row and adjacent to other buildings and foundations was

leveled, cultivated, and planted to grass. The entire Fort now presents

a clean, attractive appearance that is inviting to the public.

-- Homer Robinson, LARO Superintendent, 1963 [78] |

The two main Park Service roads on the upper bench of Fort Spokane lead to the employee housing and maintenance shop/district offices and to the parking lot near the guardhouse. As early as 1960, the Regional Office and park staff recognized the need to prevent modern developments from intruding on the "historic scene" by screening the modern buildings with plantings and a fence. The Regional Office recommended using the historic road from the highway to the guardhouse as the main entrance road, but LARO Superintendent Robinson, employing rather convoluted reasoning, objected because the historic route would "intrude very heavily on the historic scene since it will cross an open field." He favored a more "attractive" approach, shielded by a planting of box elder trees. The road was built to run straight from the state highway to the guardhouse, with parking directly in front of the guardhouse. The historic road ran a couple hundred feet to the south, midway between the guardhouse and the barn. [79]

LARO's 1975 Interpretive Prospectus emphasized the need to remove Park Service housing, the maintenance shed, and the visitor parking lot from the historic area. Most of this has not yet been accomplished. The park did remove overhead phone and power lines at the residences in 1975 and screened the houses with native vegetation a decade later. In 1978, however, the District Ranger proposed moving the parking area farther from the guardhouse, and in 1985 the entrance road was relocated to the historic road alignment to the south. The old road was reseeded to fescue and wheat grass the following year. The 1991 Comprehensive Design Plan for Fort Spokane reiterated that the service and facilities road needed to be removed from the historic site proper because it seriously compromised and jeopardized the design integrity of officers' row. [80]

When the Park Service obtained Fort Spokane, LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson tried to "clean up" its appearance. The grounds were planted to non-native grasses, and brush and weeds were removed. In the 1970s, however, the approach changed. Seventeen acres that had been cultivated to alfalfa by local farmers since 1967 under a special use permit were no longer permitted for agricultural purposes after 1976; this stopped an activity that had "clobbered" many of the building sites. The lawn around the guardhouse, however, remained. The 1975 Interpretive Prospectus recommended that after the foundations had been marked, the grounds should be returned to their appearance during the military era — tufts of grass growing under ponderosa pines. [81]

Lack of funds and other management constraints prevented LARO from immediately implementing its goal to revegetate the Fort Spokane grounds to their 1880s appearance. Letting the land lie fallow from 1976 forward created problems with fire hazard and noxious weeds, led to negative public comments, and presented an appearance that detracted from Fort Spokane's historic integrity. The revegetation of ten acres, including the main fort grounds, finally began in 1984. A 1980 University of Idaho report outlined a detailed program for restoring the plant community on the parade grounds and the area around the stables. The goal was to replace knapweed and cheatgrass with Whitmar bluebunch wheatgrass and hard fescue. The seeding did not establish well, so a 1985 study recommended ways to establish and maintain the desired species. A plan to return approximately sixty acres to a cover of drought-resistant grasses was approved, and the ground was reseeded in 1986. Most of the lawn around the guardhouse was removed and seeded with fescue/wheat grass. [82]

The 1985 design proposal for Fort Spokane's historic landscape identified significant historic landscape patterns, components, and remnants that defined the historic integrity of the fort. It also proposed ways to increase visitor understanding of the site. Recommendations included removing Park Service administrative facilities, revegetating grasslands, building picket fences and a wood and wire fence around the complex, establishing ornamental plantings, constructing a concession stable, corral, and trails, partially reestablishing the apple orchard, reestablishing the baseball diamond, and reconstructing the historic entry gate. The 1991 draft comprehensive design plan for the site integrated landscape, buildings, interpretation, and archaeological stabilization issues. Fort Spokane staff began a series of projects aimed at enhancing the interpretive environment at the site, such as stabilizing ruins and foundations, building the entry gate, constructing an interpretive trail, and modifying the access road and parking area. [83]

One element of the design plan that ran into problems was the reestablishment of the fruit orchard dating from the Indian school period. Concerns included the labor-intensive nature of the project and insufficient archaeological testing of the ground that would be disturbed. Some elements that have been completed are the reconstruction of the historic entrance gate at Fort Spokane, reseeding the grounds to native grasses, and grafting historic trees. Because no photographs of the original entrance gate were found, the park used the 1878 gate at Fort Sherman in Coeur d'Alene, Idaho, as a model. The new gate was not built in the same spot as the original because of the location of Highway 25. The gate was dedicated in 1997 with a cannon salute. It helps define the fort grounds and attract people to Fort Spokane, but it is not directly used in interpretive programs. [84]

Interpretive Trails at Fort

Spokane

|

We believe the visitors should walk around the

area in order to properly appreciate the site. This slow speed would

allow them time to recreate in their minds the structures and life that

took place during occupancy.

-- Charles E. Krueger, NPS Chief Landscape Architect, 1964 [85] |

In 1962, LARO Superintendent Robinson proposed a one-way loop road that would pass by each of the four buildings on the upper bench at Fort Spokane, with wayside signs at each building and at the entrance to the complex. The Regional Office, however, suggested a trail instead so that no road obliteration would be needed at a later date. Robinson agreed to have a rough trail built across the cultivated area to each building, but he doubted that visitors would walk the distance necessary to see the foundations of officers' row. [86]

The resulting 1.66-mile trail led to two of the restored buildings and also to a number of building foundations, some of which were defined by boardwalks or gravel. During the early 1970s, LARO staff debated the stops and the text and photographs to go on interpretive signs for this trail. Finally, in 1978 metal and wood signs made at Harpers Ferry Center were installed, and the Sentinel Trail officially opened to foot traffic in 1979. The new trail and its wayside exhibits made the old booklet on the Quartermaster Trail obsolete, along with the old numbered posts. The Sentinel Trail is the recreation area's most popular trail. [87]

|

| Ranger-led walk at Fort Spokane's quartermaster stable, ca. 1964. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2963). |

In 1985, LARO Superintendent Gary Kuiper requested assistance from Regional staff in preparing an improved interpretive trail plan for Fort Spokane. Much of the trail was obliterated by then, and some obsolete wayside exhibits needed to be replaced. Decisions were made to develop a new trail as approved in the Interpretive Plan (rerouted because the entrance road to Fort Spokane had been changed) and to replace the old wooden routed signs with anodized aluminum exhibits to match the newer ones on site. The laminated 2x4 exhibit bases were replaced with low brick pedestals made by the Job Corps Center at Moses Lake. Six exhibits remained the same, five required text revisions, and eight new ones were added. The new trail was established in 1987. LARO rerouted part of the Sentinel Trail again in 1993 based on the Comprehensive Design Plan for Fort Spokane, but visitors still had to "wander through the weeds to find the wayside exhibits." [88]

LARO established the bluff trail south of Fort Spokane in 1974, and it was used both for guided walks and for casual hikes. It was rerouted a few years later to make it more accessible. The wayside exhibits along the trail discussed area geology, the military period, and the Indian hospital. Other trail-related work included replacing non-historic boardwalks with a gravel path. [89]

Living History at Fort Spokane

Living history became popular in the United States in the mid-1960s. Within the Park Service, 114 areas offered some form of living history in 1974, often including historic firearms demonstrations. LARO was one of these. Its living history program began in 1973 with the arrival of a woman homesteader's costume sewn at Harpers Ferry Center. In 1974, the program consisted of four employees, including a Fire Control Aide, acting out incidents from 1880-1900 newspaper accounts and vignettes of civilian life. For the 1976 Bicentennial, the program included drills, inspections, target practice, and stable chores. In 1977, two resident mules were added to the program. [90]

LARO's weekly living history program grew in popularity in the late 1970s, with an average of 180 visitors sitting on or near the guardhouse porch to watch each presentation. It was the only living history program in eastern Washington at that time. A ranger welcomed the audience and gave a general history of the fort, and then uniformed troops assembled in front of the guardhouse. The troops were inspected, with "inserts" provided about activities at the fort, followed by a close order drill and the firing of blank rounds from a 45-70 Springfield rifle. The reenactors then stood at display stations and responded to visitor questions. Some years during the 1980s, one volunteer would remain in costume following the weekly program and would continue to do first-person interpretation the rest of the day. [91]

|

| Living history program at Fort Spokane, no date. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

Both visitor attendance and volunteer participation in the living history program began to decline in 1989. Most of the volunteers dressed as soldiers belonged to the Frontier Regulars based in Spokane. By 1994, LARO no longer had troops to parade, so rangers began wearing the soldier costumes again and giving weekly guided tours of the fort. The living history program, with attendance ranging from 30 to 120 visitors, remains LARO's most popular program, making it difficult to drop even though living history as an interpretive tool has fallen out of favor in some circles. The actors now use a script for their program, similar to a skit, and address various historic themes. The emphasis of the living history program is still on the military period. [92]

St. Paul's Mission

St. Paul's Mission at Kettle Falls served as a place of worship from 1847 until 1885. By 1901, only the walls, rafters, and less than half the roof remained. When the nearby bridge across the Columbia River was constructed, the bridge crew removed timbers from the building for campfires. In the late 1930s, money was raised in Spokane and Colville to restore/rebuild the mission as a part of the celebration of the 100th year of Catholicism in the Pacific Northwest. Because of the creation of Lake Roosevelt, the historic monument marking the site of Fort Colvile was relocated to the grounds of the mission. As early as 1941, the state of Washington recommended that the state legislature make St. Paul's Mission part of the state parks system. [94]

|

The twenty or so archaeological sites of the

Kettle Falls District contain one of the longest records of human life

and society in the Pacific Northwest, extending back for more than 9,000

years. . . . The natural park of Ponderosa pines covering most of the

terrace is a peaceful place where the intrusions of our modern world are

muted. This allows the visitor to dwell on the immensity and richness

of the past, at one of the great trading centers of our region. A

timeless ambience of natural beauty permits the imagination to roam

almost at will through the long centuries.

-- David H. Chance, archaeologist, 1992 [93] |

The Catholic Bishop of Spokane donated St. Paul's Mission and 2.9 acres of land to the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission in 1951. For the next two decades, local community groups helped administer the site because the nearest state employees were located ninety miles away. In 1973, LARO agreed to administer the site through an informal arrangement. Recreation area staff recommended that the state make this official by transferring the title to the land to the federal government. [95]

The state did donate the mission and 3.25 acres of land to Reclamation for administration by the Park Service in 1974. Park staff almost immediately prepared two new mimeographed booklets telling the stories of St. Paul's Mission and the Kettle Falls fishery to supplement the folder on Fort Colvile and the fur trade. In the 1970s, archaeologist David Chance did field archaeology at Kettle Falls, and the information he uncovered helped LARO improve public relations by increasing local awareness of the story to be told there. The Park Service also sponsored a historic resources study of the area that provided a narrative of the pre-reservoir history of the Upper Columbia River to aid in the interpretation of the resources, but specific information on the mission was still needed to help in planning interior and exterior restoration of the building. The Kettle Falls Archaeological District was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1974; the district includes federal land both above and below the waters of Lake Roosevelt and some private land. The district encompasses the mission and associated cemetery, an aboriginal village and burial ground, and many other features. The great number of archaeological sites made extensive development of the terrace north of Highway 395 undesirable. [96]

|

| St. Paul's Mission soon after restoration, 1941. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2788). |

LARO's 1975 Interpretive Prospectus discussed plans for the building, including doing a furnishing study, restoring the interior and exterior and grounds, and playing taped church music (in fact, worship services were held in the mission as a living history program during the Bicentennial). In the late 1970s, a film from the 1930s was shown at St. Paul's Mission. The film, made by Marcus resident Eric Harding, highlighted Kettle Falls prior to the construction of Grand Coulee Dam. By 1980, LARO personnel were leading tours of the mission. A half-mile self-guided trail installed in the 1970s included three routed-cedar wayside exhibits on the mission, Fort Colvile, and the Kettle Falls fishing grounds. These were upgraded in 1984, adding a sign at the cemetery, and the interpretive emphasis was placed near the original fishery rather than at the mission. One of the new exhibits was a grooved boulder used by Indians camping at the fishery, which was moved to the Mission Point overlook from its earlier location next to the Kettle Falls information station. The stone originally came from an area near Hays Island that is now inundated by Lake Roosevelt. Additional waysides and perhaps "sighting rings" may be placed along the Mission Point Trail and at the overlook to interpret the area's ecology, the importance of Kettle Falls to regional American Indian tribes, the significance of Fort Colvile, the cemetery, and the historic road cut from the bench to the site of Fort Colvile. [97]

The visitor contact station near the Kettle Falls campground has long suffered from its off-highway location and poor signing. In 1995, LARO built an addition to house offices and workspace for the interpretive staff and park archaeologist. The visitor center has limited displays on the history of the Kettle Falls area. Films of Kettle Falls made in 1939 are shown to visitors on an informal basis. Expanded exhibits and even a window for the public to watch the activity in the archaeologist's lab are being considered. [98]