|

Lake Roosevelt

Currents and Undercurrents An Administrative History of Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area |

|

CHAPTER 9:

From Simple to Complex: Cultural Resource Management

Cultural resource management at Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area has been fraught with challenges. Initially the needs of recreation and industry took precedence. Early park managers were not much concerned with cultural resources because the two obvious historic sites, Fort Spokane and St. Paul's Mission, were outside the original boundaries and most archaeological sites were hidden under reservoir waters. This changed in the 1960s with the acquisition of Fort Spokane, passage of the National Historic Preservation Act and subsequent legislation, and the start of drawdowns for construction of the third powerhouse at Grand Coulee Dam. Today there are four federal agencies, two Tribal Historic Preservation Offices, and one State Historic Preservation Office — with the shared goal of resource protection but often differing agendas — who participate in some capacity in the complex task of cultural resource management at Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO).

Grave Removal and Columbia Basin

Archaeological Survey, 1939-1940

Archaeological investigations of the reservoir area were essentially an afterthought in the late 1930s, during the bustling period of construction at Grand Coulee Dam and the associated reservoir clearing. Elsewhere in the country, the Tennessee Valley Authority had conducted salvage archaeology operations at each of its major reservoirs during the 1930s, but the United States Bureau of Reclamation (Reclamation) did not play any serious role in archaeological investigations until the (Missouri) River Basin Surveys Program in the mid-1940s. Nonetheless, Reclamation got involved, at least peripherally, with a hurried program of archaeological salvage at the Columbia River Reservoir (Lake Roosevelt) in 1939-40. [1]

One non-archaeological aspect of the project began ca. 1938 when the tribes became concerned about the imminent flooding of their cemeteries at various locations along the Spokane and Columbia rivers. The Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) intervened on their behalf and began negotiations with Reclamation for relocation of known cemeteries as well as isolated burials. This function was later formalized in the Act of June 29, 1940 (Acquisition of Indian Lands for Grand Coulee Dam, 54 Stat.703). That legislation authorized the Secretary of the Interior to acquire Indian cemeteries, essentially trading them for new lands to be used for the same purpose. All human remains, grave markers, and "other appurtenances" were to be removed to the new site, with costs borne by the Grand Coulee project. [2]

Work began in September 1939 when the Spokane undertaking firm of Ball & Dodd was awarded the contract to relocate both Indian and non-Indian graves away from the area to be flooded; this was strictly a burial relocation project, separate from the subsequent archaeological investigations. The locations of most Euroamerican cemeteries were known, but Reclamation hired non-Indian resident Cull White and knowledgeable tribal members to help locate Indian burial sites. Other Indians worked for Ball & Dodd building wooden boxes to hold human remains; these containers were small, just long enough for the leg bones and deep enough for the skull. (It is not known if the remains of non-Indians were reboxed in the same fashion or not.) During the process of exhumation of Indian burials, workers discovered hundreds of artifacts that had been buried with the deceased. Many of these were not reburied with the bones and instead were collected for their intended return to the tribes. Archaeologists who followed Ball & Dodd a year later called the undertakers' work a "major calamity, from the archaeological point of view" because their methods of exhumation completely destroyed all scientific evidence. [3]

Accounts vary concerning the total number of graves that were relocated with such haste in late 1939. Reclamation reported a total of 915 graves moved at a cost of $19,642.60; another source listed the reburial bid as $10,728. Howard T. Ball, who supervised the field work, initially reported that his crews relocated 1,027 graves, but he later changed this figure to 1,388. Tribal leaders reported another 2,000 sites in the fall of 1940, with additional discoveries expected, but Reclamation refused to continue the relocation. All remaining graves were soon covered with water. [4]

Archaeological recovery was first considered when the Inland Empire Indian Relics Society approached Reclamation in 1939 with a plan to have an archaeologist supervise a crew hired by the Work Projects Administration (WPA) to conduct salvage archaeology in the reservoir area. Neither Reclamation nor WPA had funds for such work, however. The Relics Society then joined with the Eastern Washington State Historical Society, which provided funding for a reconnaissance survey of the reservoir area from the dam to the Canadian border. When that was completed, the University of Washington and State College of Washington (later known as Washington State University) accepted archaeological oversight of the Columbia Basin Archaeological Survey (CBAS). The Historical Society also interested the National Youth Administration in providing manual labor and camp costs for field work that began in the fall of 1939 and continued for a year, with numerous test excavations at promising locations. Crews concentrated on three kinds of locations: habitation sites, shell middens, and burial sites; the last contained the most artifacts. [5]

This first archaeological project has been strongly criticized by recent archaeologists for both its methods and conclusions, but it is clear that the staff struggled with a difficult situation in 1939-1940. Time was limited as the waters rose relentlessly, forcing the inexperienced crews to move farther up the reservoir. They were pushed to work rapidly and often "superficially . . . as the water lapped about our heels," they reported. Supervisory personnel changed several times, and those remaining had trouble making sense of others' field notes. Heavy sod cover protected and hid many sites that have been found by subsequent archaeologists. The CBAS conclusions that the area was sparsely populated and the cultures were "simple" have since been disproved. More recent archaeologists have been able to find many additional sites that have been exposed after decades of water fluctuations and wave action eroded banks. The layers of stratigraphy have been destroyed, however, making interpretation difficult. [6]

Cemetery removal continued to be a problem for Reclamation, especially during the first decade of the reservoir when the banks continued to shift as they sought a stable angle of slope. Crews moved forty burials, for under $725, from the Klaxta cemetery in 1941 when the site was at considerable risk of sliding into the water. Another 850 graves from four slide areas were located in 1949 and removed the following year for approximately $20,000. Reclamation placed riprap on part of the Spokane Arm to protect a cemetery in 1965, slowing erosion at the site. In a much smaller project in April 1972, Barnes Funeral Home in Grand Coulee removed parts of sixteen burials in scattered graves along the Spokane River and reburied them in a common grave in the Westend Presbyterian Cemetery, at the request of the Spokane Tribe of Indians (STI). The tribe also asked that any artifacts found with the graves be turned over to the tribe. Some high banks continue to slump as they erode toward a new angle of repose. Such activity threatens the sites at Mission Point, requiring regular monitoring by the LARO archaeologist. [7]

Archaeology, 1940-1960

When the Park Service began studying the Columbia River Reservoir, the agency was interested primarily in the area's recreation potential. Nonetheless, Regional Director Herbert Maier wrote to Joel Ferris in 1941 to ask if the Coulee Dam area had any archaeological or historical values. Ferris, vice president of the Eastern Washington State Historical Society, had been the key figure in funding the work of the CBAS. He believed that the reservoir area contained many sites with both historical and archaeological value, but his own interests lay with sites outside the reservoir. His believed that Fort Spokane was worth restoring but of lesser historical interest than Spokane House or sites in the Colville area. [8]

Following World War II, federal agencies began to pay more attention to archaeological resources that were scheduled for destruction as a result of a federal action. Consequently, salvage archaeology projects increased in connection with highway, pipeline, and canal construction. In August 1947, Reclamation, the Park Service, the Smithsonian Institution, and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers cooperated with the universities of Oregon, Washington, and California on a survey and salvage project in the Grand Coulee, prior to the dam and flooding that turned it into the Equalizing Reservoir, now known as Banks Lake. The project was led by Philip Drucker from the Smithsonian, who had worked nearly a decade earlier on the CBAS. Within two weeks, crews had located approximately twenty-five sites with burials, artifacts, and pictographs. Their primary work included sampling at some sites and sketches of rock art. [9]

The Park Service employed few archaeologists during the 1940s. Jesse L. Nusbaum worked out of the regional office in Santa Fe in 1947, but he covered a vast area including much of the western United States and Alaska. Along with the established parks, he had to survey areas that were potential additions to the National Park System, such as the Equalizing Reservoir, as well as all Department of the Interior lands in eleven western states and Alaska. With responsibility for such a large territory, there was little time to concentrate in any one area. By 1960, the regional office in San Francisco had its own archaeologist available to either do the work himself or help parks contract with qualified outside personnel. The Regional Director reminded superintendents to watch for archaeological resources during construction projects. He suggested inspecting any proposed construction areas prior to work and, if archaeological evidence was seen, the staff should stop the project until the site could be investigated. If this were not possible, they should salvage the site. LARO depended on both Park Service and private archaeologists until 1993 when the park hired its first full-time archaeologist. [10]

Archaeology, Early 1960s

Following the conclusion of the CBAS in 1940, there was no further archaeological work at LARO until the 1960s. Initial emphasis was at Fort Spokane, acquired by the Park Service in 1960 and scheduled for extensive development under the Mission 66 program. The Western Regional Office funded preliminary excavations at Fort Spokane in August and September 1963. John Combes and his students from Washington State University (WSU) located footings and artifacts associated with the 1880-1882 Camp Spokane and then turned their attention to foundations of the main fort. The results were so satisfying that the Park Service proposed continuing the work of uncovering and stabilizing foundations to help interpret the site. [11]

Work on a new Master Plan in 1963 indicated deficiencies in the archaeological knowledge of the park. Regional personnel proposed to remedy this with an archaeological survey conducted by WSU in FY1965-1967 for $15,000. Superintendent Homer Robinson questioned the need for this survey because of the archaeological work done by the CBAS in 1939-1940, but others assured him that the survey was definitely warranted. Robinson followed up with three research project proposals to cover the archaeological survey, historic structures studies at Fort Spokane, and a study of building furnishings at the fort. [12]

Funds were not immediately available for any work, however. Although the Regional Archeologist had requested money for surveys at LARO each year, his budgets were "cut to a bare minimum" for research funds. He asked Superintendent Robinson if there were any chance that the park's Natural History Association had any funds to help with an important salvage project at Kettle Falls. If so, he believed the regional office could "scrape up some funds at the end of the year" to match money from the Association. Robinson's reply was far from encouraging: "The Coulee Dam Nature and History Association has a balance of $15.43 in the bank and we doubt that much could be done with this amount. Are there any other possibilities?" [13]

Federal Legislation Governing Cultural

Resource Management

Prior to 1966, two major laws affected archaeological and historical sites. The Antiquities Act of 1906 established a system of permits for any archaeological work on federal lands. This was followed by the Historic Sites Act of 1935 that mandated the National Park Service to identify important cultural resources and provide for their protection and preservation. [14]

The landmark National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 (NHPA) greatly expanded protections by requiring the federal government to implement a nationwide program to identify, protect, and preserve historic places. This process was mandatory for all federal agencies as well as any project involving federal dollars. Compliance oversight rested with a newly created national Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. [15]

Other legislation expanded the mandate to identify and protect cultural resources. The Archaeological Recovery Act (also known as the Reservoir Salvage Act) of 1960 provided for salvage of archaeological sites prior to dam construction. The National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA) required federal agencies to consider the impact of their actions on environmental, historical, and cultural resources, whether on federal land or on private lands using federal monies. This ushered in the era of environmental impact statements. Ten years later, the Archaeological Resources Protection Act of 1979 (ARPA) and subsequent amendments tightened protection for archaeological sites on federal lands and provided for criminal penalties. [16]

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990 (NAGPRA) directed museums, universities, and all federal agencies to inventory their collections of human remains and associated grave goods, determine cultural affiliation where possible, and notify appropriate tribes. If they wished, tribes could ask for skeletal remains and artifacts to be returned to them. The sections of NAGPRA governing inadvertent discoveries of burials strengthened the tribal role in cultural resource management of reservoir lands such as LARO where the actions of reservoir operators caused slumping of banks and exposure of burials. When cultural affiliation is clear, the law gives tribes custody of such human remains. At the same time, federal land managers still have responsibilities under Sections 106 and 110 of NHPA and under ARPA. [17]

Impact of Third Powerhouse

Construction

Funding possibilities for archaeological work at LARO improved with Reclamation's construction of a third powerhouse at Grand Coulee Dam. To facilitate building this project, the agency needed to dramatically lower the water in Lake Roosevelt each spring, an action that would expose hundreds of archaeological sites never before recorded. To prepare for this anticipated archaeological bonanza, the Western Regional Office funded WSU for the 1966 and 1967 seasons to do survey work around much of the reservoir. The Park Service continued the same funding arrangement for two more years as the lake levels dropped. [18]

Late in 1967, the Park Service initiated discussions with Reclamation about additional funding for a major archaeological salvage program at Lake Roosevelt during the powerhouse construction. Regional Archeologist Paul J. F. Schumacher stressed the importance of the sites that would be exposed and recommended that Reclamation provide $37,000 per year in 1968, 1969, and 1973, the years of the lowest expected drawdowns. He also requested $17,000 for each of the other three years, bringing the total to $162,000. The expenses were higher than normal since they would need to hire a field crew on the open market instead of being able to use low-cost student workers who were available only during the summer months. [19]

|

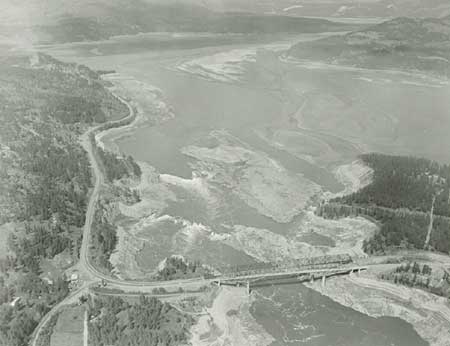

| Aerial view of Kettle Falls, partially exposed during drawdown in April 1969. The large drawdowns during construction of the third powerhouse enabled archaeologists to reach previously inundated sites, including some particularly significant ones at Kettle Falls. Photo courtesy of U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Grand Coulee (USBR Archives P1222-142-45-46). |

Reclamation initially refused this request, saying that it was not mandated to fund such work in the Columbia Basin. Schumacher pointed out that the Public Works Act each year specifically made Reclamation appropriations available to cover costs of archaeological and paleontological projects. In addition, he said that the Park Service could not afford to do salvage work for sites threatened by other agencies, but it could offer advice, inspection of salvage archaeology, and review of technical reports from the salvage projects. Although the budget for the third powerhouse was "extremely tight," Reclamation managed to find $5,000 for archaeological salvage work in the FY1968 budget and expected it could make similar adjustments in FY1969. Schumacher stressed the need to have a crew in the field during the 1968 drawdown to show pot hunters that both federal agencies and professionals were interested in preserving the local heritage. He requested substantially more money for subsequent years. [20]

The drawdowns for the powerhouse project during the late 1960s and early 1970s spurred significant archaeological work at Lake Roosevelt. Supervision changed from WSU to the University of Idaho in 1970, about the time Reclamation assumed responsibility for funding the work. Projects included extensive surveys around the reservoir and excavations concentrated in the Kettle Falls area. Archaeologist David Chance provided the primary field supervision for crews working at several sites connected with the fishery at Kettle Falls. Analysis of the features recorded there and materials recovered over several years of work enabled Chance and others to develop a local cultural sequence using artifact assemblages; develop a dated cultural chronology that indicated use of the site starting ca. 9,000 years ago; and describe the earliest known subsistence-settlement patterns in the reservoir area. In addition to prehistoric sites, archaeologists also conducted extensive investigations during the drawdowns at the site of Fort Colvile, the Hudson's Bay Company trading post near Kettle Falls. Work during several seasons helped provide information about building design and fort layout as well as details about both Indian and non-Indian life at the fort. [21]

|

| Part of Takumakst (the Fishery), an Indian village at Kettle Falls, 1861. This site was partially excavated during the drawdowns for the third powerhouse construction. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3246). |

Funding achieved a certain stability by the mid-1970s. Prior to 1976, appropriations from Reclamation for archaeological work at Lake Roosevelt had been on an annual basis, with the Bureau funding the Park Service which, in turn, contracted with the University of Idaho for the salvage work. For instance, the contract in 1971 amounted to $30,000 to be spent primarily on work at Fort Colvile and five prehistoric sites. In 1976, Reclamation began contracting directly with the University of Idaho. The first contract covered three years, providing a financial predictability that aided both field work and analysis. [22]

Pot Hunting and Inadvertent Site Destruction,

1960s-1970s

Major drawdowns during the powerhouse construction enabled archaeologists to reach previously inundated sites, but they also provided access for local pot hunters whose interest was stimulated by the professional excavations. Monitoring the shoreline for violations became a concern for both field archaeologists and the Park Service. Archaeologists Edward Larrabee and Susan Kardas, who conducted a survey in 1966, found pot hunters "very active" during low water and warned that continued drawdowns posed an emergency situation. "It is very much going to be a case of [archaeologists] getting there before the pot hunters do and staying until the floodwater comes up," warned Larrabee, "because I think it will be almost impossible for the Park Service to patrol this area." He suggested concentrating work in 1967 on the most threatened sites. [23]

The Park Service tackled the problem head-on the following spring by apprehending violators, especially at Fort Spokane, and by alerting the public to provisions of the Antiquities Act through press releases distributed to local television and radio stations and seventeen newspapers. LARO began to work with the U.S. Attorney's office to develop procedures to deal with repeat offenders. The education campaign continued in 1968 with the Park Service and regional archaeologists cooperating on a series of articles dealing with both legal and scientific issues surrounding archaeology. Carl Anderson, Kettle Falls District Ranger, suggested using the educational approach to the pot hunting problem, but he warned, "It's going to take a lot of effort on our part to educate the public because of our indifferent attitude in the past." [24] Active participation by LARO staff, including citing flagrant violators, reduced the problem with vandalism by 1970. "This was all quite different from the rather depressing situation I encountered three years ago," wrote David Chance, expressing his gratitude to the Park Service. By 1976 Chance believed the problem had dropped to an insignificant level due to active patrolling of sites by LARO rangers. [25]

LARO staff had to adjust to the increase in archaeological activity. While early patrolling was far from perfect, their response to the problem of pot hunters showed a determined and creative effort to meet their new responsibilities of identifying and protecting sites. Not everything went smoothly, however. Superintendent David Richie appealed to WSU archaeologist Lester Ross in 1969 for help in preventing destruction of archaeological sites. That spring, bulldozer crews working on the Reclamation log boom at China Bend inadvertently destroyed four sites. Both Richie and Ross attributed this to a lack of communication between contracting archaeologists at WSU and the staff of the federal agencies at Lake Roosevelt. Ross offered three suggestions to improve the situation: archaeologists needed to inform the agencies of sites being considered for further study; agencies needed to tell the archaeologists about any potential activities that would alter the land; and finally, the archaeologists needed to investigate these areas prior to making recommendations for mitigation or avoidance. Richie believed that Ross's recommendations would place an undue burden on all parties, and he proposed basically that all known sites be mapped, allowing the agencies to see if proposed activities might cause any destruction. If there were potential for harm, the university would investigate prior to clearance; if no potential, the agency could proceed. The Park Service would advise anyone working along the lake, whether federal or private, that all work had to cease if they found "obvious evidence of archaeological remains." [26] It is not known what protocols were adopted, if any.

|

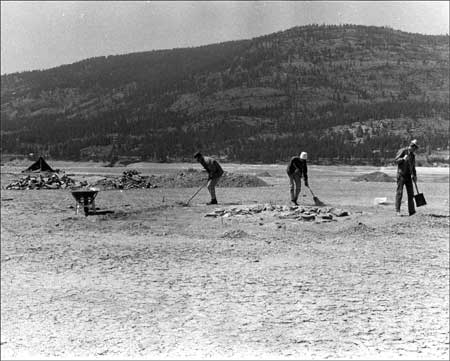

| Excavation of site at Kettle Falls. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO.FS). |

LARO staff did not always follow proper procedures concerning archaeological resources. Park Service Regional Archeologist Charles Bohannon went to LARO in 1978 to provide archaeological clearance for a new access road, only to find the rough grading already completed. The following spring, the Regional Director took LARO Superintendent William Dunmire to task for providing clearance for another small project without the benefit of an archaeologist. While the particular situation appeared relatively unimportant to the Regional Director, he reminded Dunmire that "the archeological community and the State Historic Preservation Officer have shown no hesitation in raking Federal agencies over the coals for even minor projects such as this." He was concerned that many such instances over the years could have "a drastic accumulative effect." [27]

National Register of Historic

Places

The 1966 NHPA helped the Park Service create a formal program for the management of cultural resources. By early 1969, the agency began to push all park units to identify historic resources and prepare forms to nominate sites to the recently created National Register of Historic Places, as called for in the federal legislation. President Richard Nixon strengthened this movement with Executive Order 11593 on May 13, 1971, mandating federal agencies to begin preservation of historic properties under their jurisdiction and to nominate these to the National Register by July 1, 1973. The deadline was a year earlier for the Park Service so it could provide an example for other agencies. In addition, its early response would reduce the anticipated heavy workload for the National Register staff. [28]

LARO staff did not meet the July 1972 deadline for this major project. Their work was complicated by a controversy over including the inundated sites of Fort Colvile and Kettle Falls. While state and federal officials did not think that any sites lost to the reservoir were eligible for the National Register, Park Naturalist Art Hathaway believed they should be included. He asked archaeologist Roderick Sprague for guidelines for nominating archaeological sites or alternative means of protecting them. State officials then evidently changed their minds on this point and the Kettle Falls Archaeological District, including seventeen prehistoric sites as well as the site of Fort Colvile and St. Paul's Mission, was added to the National Register in 1974. Its listing caused controversy, this time with the Park Service objecting to state actions. The Washington State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) had nominated the district without any review by either the Park Service or Reclamation. Acting Regional Director Wayne Howe recognized the SHPO's authority in this matter but suggested that this type of unilateral action would worsen relations between state and federal agencies. He requested procedures to ensure that federal agencies be allowed to comment on state-initiated nominations in the future. Fort Spokane's nomination generated less controversy. The form, drafted in 1972, was later extensively revised before the district was listed in November 1988. [29]

Fort Spokane

When the Colville Indian Agency took over Fort Spokane in 1900, the buildings required a great deal of maintenance. Most were dismantled, relocated, or lost to fire and vandalism over the following decades. In 1918, when the hospital opened, only two of the standing buildings were occupied, and several were soon demolished. Most of the remaining structures were removed between 1930 and 1960, and the orchards, gardens, and fences were abandoned. Local farmers often used open areas for pasture and for raising cultivated crops, and area residents continued to use the site as a picnic spot. A caretaker for the Indian Service lived on the grounds. In 1940, as part of the Grand Coulee Dam Project, some 310 acres were transferred to Reclamation. The remaining 331.31 acres, on the higher bench, remained under the jurisdiction of the Bureau of Land Management. [30]

Beginning in the 1920s, agencies and individuals suggested a number of possible uses for Fort Spokane. The Washington Natural Parks Association thought it could be a state park. Some people in Spokane wanted to preserve it as an historic monument. The residents of Lincoln, at the mouth of the Spokane River, originally planned to relocate their town to the site of Fort Spokane when their townsite was flooded by the new reservoir, but this turned out not to be possible. The Lincoln County Historical Society and Spokane Chamber of Commerce wanted the buildings to be restored. The Park Service became interested in the site's possibilities as early as 1941, during the planning process for recreation on Lake Roosevelt. The agency asked to take over jurisdiction of the fort lands in 1943 and again in 1946 when the Tri-Party Agreement was signed. The Bureau of Land Management agreed to the transfer, but in 1949 the Spokane Business Council asserted its interest based on aboriginal use and occupancy. The STI hoped to develop the area for recreation and operate it to produce income for the tribe. As a result of the STI protest, a 1951 Solicitor's Opinion held that any withdrawal of the lands for inclusion in LARO had to be authorized by Congress. This delayed the decision for a number of years. [32]

|

The upper level [of Fort Spokane] could well be

preserved for the historical monument and a small amount of work on the

existing structures would preserve them for all times. Some of the old

frame buildings probably should be removed as not being of sufficient

interest to warrant the great amount of work necessary for their

preservation.

-- Philip A. Kearney, NPS Landscape Architect, 1942 [31] |

During the 1940s and 1950s, while the Park Service was waiting on authorization to use the land outside of LARO's boundaries at Fort Spokane, the agency continued planning and developing facilities on the lower bench on land that belonged to Reclamation. The site was seriously considered for administrative headquarters in the 1940s. Although the regional office continued to urge evaluation of the historic qualities of the remaining buildings, LARO Superintendent Greider saw little value in them, or in the site's potential for LARO headquarters, as evidenced by this 1949 telegram about Fort Spokane: "Frame buildings have been removed. Brick buildings and old stable only good for salvage of brick and timbers. Fort Spokane satisfactory for district ranger station but not for general area headquarters." [33]

During the 1950s, Park Service personnel had mixed feelings about the historical significance of the few buildings still standing at Fort Spokane. In 1952, the Park Service revised its Master Plan for Fort Spokane to exclude the area occupied by the fort. In submitting this plan to the Park Service Director, Sanford Hill, Park Service Assistant Regional Director, explained that "Dr. Neasham [Park Service historian] does not believe this fort is of sufficient National importance to warrant acquisition or possible restoration by the National Park Service." The Park Service was trying at that time to reach a compromise with the Bureau of Indian Affairs whereby the Park Service would acquire only those acres that it absolutely needed for development of a recreational site at Fort Spokane. By 1957, however, the regional office again was stating in correspondence that one or more of the remaining buildings at Fort Spokane should be stabilized and used for administrative, interpretive, or other purposes. Regional staff did not believe that the fort had national significance, but they did agree that its state and local values were worthy of recognition. The primary purpose of acquiring the upper bench, however, according to LARO Superintendent Homer Robinson, was to develop a water system from the historic spring that had served the fort and to provide land for Park Service residences and a utility area away from the public-use area down on the lower bench. The regional office reminded Robinson that the Park Service had a national policy of preserving historic sites and structures and that any proposed development of Fort Spokane should not intrude on the historic scene. [34]

Building Restoration at Fort

Spokane

Once the Park Service acquired the Fort Spokane grounds in May 1960, it immediately began to develop plans for the historic buildings. Regional Historian John Hussey visited the site and reported that even though only a few buildings remained, they gave the fort both the appearance and atmosphere of a frontier post. Restoration of the buildings was feasible, despite considerable cost. He stressed the need for immediate stabilization and protection prior to the arrival of an architectural team later in the summer. Preservation and restoration of the remaining buildings at Fort Spokane began in 1961 with some stabilization work. In 1962 LARO established maintenance accounts to retard deterioration of the buildings. The Mission 66 prospectus was revised to include funds for a visitor center at Fort Spokane plus money for research on stabilizing and restoring the standing buildings and to stabilize the foundations of the officers' quarters. [35]

Work in the early 1960s consisted of the various steps necessary to prepare the Historic Structures Report for Fort Spokane, which was written by Park Naturalist Paul McCrary. This report presented renovation and reconstruction priorities for the historic buildings. Restoration began in 1965 on the 1892 guardhouse, 1888 powder magazine, 1884 stable, 1883 reservoir building, and 1880s springhouse. Naturalist McCrary worked alongside the maintenance crew on the restoration; he was young, had diverse skills, and was willing to tackle large projects. The work was completed to acceptable levels, according to the standards of the day, by the early 1970s. The quartermaster storehouse was in very poor condition and was torn down by 1980. LARO staff learned in 1963 that the former post sutler's house was located in Miles, but the owner's asking price was too high and the Park Service did not purchase the building. [36]

The guardhouse was a priority for work in the early 1960s. It was rather extensively remodeled on the interior to serve as district offices and exhibit rooms. Structural timbers missing from the building were replaced, and "modern conveniences" were installed. The ceilings were lowered in some rooms, and doors and window sashes were constructed to match the originals. The interior rooms became the district ranger's office, exhibit room with central information desk, ranger work room, seasonal historian office, prison exhibit room, two cell exhibit rooms, audiovisual room, furnace room, employee restroom, storage room, and hallways. Rooms opening onto the veranda were converted to public restrooms. The work was completed in 1966. According to LARO Superintendent David Richie, writing in 1968, "Most of the historic atmosphere of [the guardhouse lobby] was lost during restoration." [37]

|

| Fort Spokane guardhouse and quartermaster stable soon after restoration, 1966. Photo courtesy of Spokesman-Review archives. |

One seasonal employee, Tom Teaford, was quite disturbed by an experience he had while working in the guardhouse in 1978 or 1979. Teaford was sitting behind the information desk late one night when he heard slow footsteps walking along the hallway. The door to the men's restroom (the access was from the hall at that time) swung open and closed. Next, he heard a group of children talking and laughing on the front porch. He called the night patrolman, but the two men found no evidence of intruders. In fact, there were no footprints in the sprinkler-moistened lawn surrounding the building. This story is still told to new LARO employees at Fort Spokane to share with them the past historic uses of the property as an Indian school and children's hospital. [38]

Around 1983, the district offices at Fort Spokane were removed from the guardhouse to a nearby new building. LARO began discussing changing the layout within the guardhouse, such as removing nonhistoric walls. The chrome and vinyl office furniture had been replaced with wooden furniture back in 1974, but modern lights, double doors, and modern flooring still detracted from the historic feel. The interior of the building had dark carpets and dark walls. In 1996, office partitions were removed, the brick walls were exposed, and a new information desk, sales area, and staff workspaces were provided. This was partly necessitated by changing exhibits and the addition of cooperating association sales fixtures. The lobby was made to look more like exhibit space than offices in order to make it more inviting to visitors. [39]

The quartermaster stable is a large frame building that Fort Spokane's caretaker was using for storage when the Park Service acquired the property. The 1962 Historic Structures Report for this building determined that LARO would "recreate the scene" to some extent with stable items and would refurnish the stable sergeant's room. The building was stabilized and leveled with new foundation beams in 1964. Park staff had no idea how heavy the cupola was until they tried to raise that section. They used surplus twenty-ton jacks, burying three jacks before the section even moved an inch. LARO's Maintenance Foreman Don Everts remembered that the park engineer often observed the work. "Of course, this was before OSHA, so he'd shake his head and turn around quite often." [40] In 1973, park personnel screened the north end of the stable so the public could view the interior. A 1975 paint job removed the white trim that had made it look like a New England barn. The following year, the flooring of the interior north half was replaced and that part of the stable was opened to the public. Other work in the 1970s, related to the living history program, included acquiring two mules, a freight wagon, and harness, as well as constructing a vertical-board corral next to the stable based on historic photographs and drawings. The final major work at the stable was done in 1985, when maintenance crews installed a new foundation, posts, flooring, and stall partitions in the south end of the stable. [41]

When the Park Service took over the upper bench of Fort Spokane, the powder magazine was the best preserved of the buildings that were still standing. The early 1960s work on this brick building consisted of realigning the foundation and stabilizing the building, plus installing new doors and windows to match the originals. In 1974, the front part was used for cataloging artifacts with room for public viewing. Exhibits were installed in the building in 1977, and the exhibit room was opened to the public in 1978. Today, a table from the post bakery and two cook stoves are on display in the room. [42]

The historic water system at Fort Spokane is a spring about four hundred feet above the other historic buildings on the site. In 1963, the springhouse and reservoir building were rehabilitated/rebuilt and new pipes were laid. The gravity-flow water system provided water to the employee residences, picnic area, and campground at Fort Spokane. The reservoir building was again stabilized in the mid-1980s. [43]

Beginning in fiscal year 1978, four buildings and numerous foundations at Fort Spokane were included in LARO's Historic Building Cyclic Maintenance Program (the springhouse is not a contributing element of the district). Most of the work consisted of painting and foundation stabilization. The Fort Spokane Military Reserve Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1989. [44]

In 1985, two landscape architects from the Pacific Northwest Regional Office (today's Columbia Cascades Support Office) prepared a preliminary historic landscape study of Fort Spokane. Recommended work on the buildings included expanding the corral east of the quartermaster stable and establishing a maintenance program with priorities and guidelines for maintenance and restoration planning. The Historic Structure Preservation Guide for Fort Spokane was prepared in 1985. [45]

Protection of the historic buildings at Fort Spokane from fire has long been a concern. In the early 1960s, hose boxes and fire hydrants provided minimal protection. In 1981, a fire truck with a five-to-ten-minute response time was considered only marginally effective, but foot patrols, hazard inspections, mowing around buildings, and fire prevention messages to visitors helped. LARO and the Denver Service Center agreed that a small sprinkler system designed to delay fire spread until a truck could arrive would be desirable. Currently, the Park Service maintains a fire truck on site at the adjacent South District office. [46]

Fort Spokane's buildings have been infested by various pests over the years, including termites, pigeons, bats, and marmots. The park launched an all-out war against Fort Spokane's marmots in 1991. After evaluating various options, the selected methods of control were "direct reduction with firearms" and live trapping. [47]

Building Foundations at Fort

Spokane

The 1961 Historic Structures Report for Fort Spokane mentioned that archaeological testing was needed to determine the exact number of building foundations still existing and to locate the earlier buildings in order to protect them. Archaeological investigations at the site began in 1963, the first at LARO in the relatively new field of historical archaeology. This initial work concentrated on foundations. LARO personnel had worked that spring to clear debris, brush, and old fences from the fort grounds and in the process located a number of old foundations not previously documented. Much of this work was done by maintenance worker Don Everts, who "witched" the water lines leading to the foundations. WSU Archaeologist John Combes brought in a crew of students late that summer to work on locating building remains from the earliest period, 1880-1882, when the fort was still known as Camp Spokane. When this work was finished, the crew turned its attention to the main fort, where they dug within the foundation of a large building that once had contained several shops. Through their excavations and subsequent artifact analyses, they were able to delineate the areas used by the blacksmith, wheelwright, tinner, carpenter, and painter. [48]

LARO finished its initial program of stabilizing and restoring foundations at Fort Spokane in 1972. The following year, the recreation area began to locate and identify additional historic foundation stones to reduce inadvertent damage by LARO staff (some had been repeatedly plowed over). As of 1975, about thirty-one foundations and ten building depressions were deteriorating due to weather, vegetative growth, and rodent activity. Many of these were enumerated in LARO's List of Classified Structures, but a number were rapidly deteriorating because very little maintenance or protection was done on the foundations until the early 1980s. In 1981, however, the Park Service approved a project to stabilize and preserve sixteen granite foundations and two brick-lined root cellars. The University of Idaho contracted in 1985 to excavate the Company G root cellar. Following the excavations, the masonry walls were stabilized and the hole was filled with sterile sand. Foundations at two additional sites were restored in 1994-1995. [49]

|

| Excavation of root cellar at Fort Spokane, May 1985. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 2950). |

In 1991, cultural resources staff of the Park Service regional office in Seattle prepared a comprehensive design plan for Fort Spokane. One element of the plan was treatment of the foundations. The report recommended protecting and delineating archaeological features. To enhance the visitor's understanding of the historic scene, the authors proposed a variety of treatments of individual foundations, including outlining, raised walls, platforms (with floor plans painted on the surface), and "ghosted" frames. Park Service thinking had come a long way from 1968, when LARO's Master Plan called for examining the possibility of reconstructing certain Fort Spokane buildings to serve as an overnight lodge, restaurant, or gift shop run by a concessionaire. As an appendix in the report, Regional Archaeologist Jim Thomson commented that because of funding limitations, foundations should be identified and stabilized, but archaeological testing and "ghosts" were too costly to be considered. [50]

Excavations at the Fort Spokane

Dump

The historic dumping areas at Fort Spokane have attracted pot hunters for years, challenging LARO's ability to protect these sites. The main dump was discovered inadvertently in 1967 while bulldozing in the area. Trash included bottles, mugs, and buttons. The district ranger planned to monitor the area closely to prevent vandalism, but the site was regularly looted. Still, LARO staff tried to maintain a semblance of control by contacting violators to ensure future cooperation. When pot hunting continued, LARO Park Naturalist Arthur Hathaway asked Regional Archeologist Charles Bohannon to excavate the main military dump. Bohannon denied the request, adding that LARO was responsible for site protection. A major illegal excavation in the spring of 1973 encouraged the park to look into having an archaeologist investigate the site in the belief that professional excavation would discourage pot hunting by removing the attraction. LARO staff wrote a Resource Study Proposal to hire University of Idaho archaeologist Roderick Sprague to work at the site, but funding was not available. The park continued with its monitoring program, adding other areas on the grounds where smaller dumps were found. Looters continued their activities also, and there were at least seven reported incidents from 1988-1998. One of these, in January 1994, resulted in disturbance of an area as large as forty-eight square meters, with excavations going deep enough to destroy nearly twenty cubic meters of the dump; no arrests were made in this case. Four years later, the Park Service finally hired an archaeologist to inventory and analyze the artifact concentrations in the main dump. [51]

St. Paul's Mission

St. Paul's Mission presented different issues for the Park Service since it was not added to LARO until 1974. The building, constructed in 1847 using traditional post-and-sill design, fell into disuse after 1873 and partially burned in 1910, the same day that the old buildings at Fort Colvile caught fire. The damaged structure deteriorated further for nearly three decades until regional Catholics joined with a local service club and many individuals to fund a major restoration project in 1939-1940. Father Paul M. Goergen, who oversaw the work, noted that all the workers on the project had come to appreciate the skill and hard work of the original builders. "Even we, who have modern equipment to work with, find restoration of the mission difficult and exhausting work," he admitted. The Catholic Diocese of Spokane deeded the church property to the State of Washington in 1951, and the state turned administration of the site over to the Park Service in 1974. [52]

Cultural Landscapes

Obviously, not all historic sites at LARO received the intensive protection and interpretation given to Fort Spokane and St. Paul's Mission. Nonetheless, the Park Service had a mandate to conserve not only the natural environment but also the "historic objects" within it. Park managers often had difficulty deciding how to manage old buildings, and the ambivalent attitudes of certain early LARO superintendents toward the historic structures at Fort Spokane probably were typical of the era.

To help provide guidance, the Park Service initiated a pilot program in 1979 to assess cultural landscapes that included not just buildings and structures but the surrounding areas as well. This method of analyzing properties gained acceptance during the 1980s, and the Park Service now funds cultural landscape work as a distinct resource type. Landscape architects with the cultural resources division in the regional office in Seattle conducted a preliminary landscape study of Fort Spokane in 1984, followed by a cultural landscape report (CLR) and design proposal. The regional staff then continued to work closely with LARO personnel to consolidate the findings from the Fort Spokane CLR, completing a draft Comprehensive Plan for the site in 1991. Although the plan was never finalized, it addressed many of the issues raised in the earlier CLR. LARO staff at Fort Spokane used this plan as the basis for a series of projects to enhance the interpretative environment at the site. These included stabilizing foundations and ruins, designing the entry gate, building an interpretive trail, working in the historic orchard, and modifying the access road and parking area. Natural resource management at LARO also considered cultural landscape issues when managing for hazard trees, insect infestations, and fires. [53]

The Park Service instituted a service-wide Cultural Landscape Inventory to document and evaluate any park landscape that was potentially eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Work on this inventory at LARO began in 1994 when two landscape architects from the regional office worked during the spring and summer to identify and inventory nineteen potential cultural landscapes at LARO; they identified fifteen others for additional work the following year. The sites ranged from Grand Coulee Dam, with its associated irrigation features and towns, to isolated homestead cabins and farms, to Fort Spokane. The work in 1994 was funded by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA) as part of a multi-disciplinary inventory that was incorporated into the research design of a much larger project, described later in this chapter. The inventory work is not yet completed. [54]

Museum Collection Management

Park Service museums use artifacts to illustrate interpretive themes. Museum collections at park units generally contain a number of artifacts suitable for exhibit, along with many others appropriate for study. Many of these artifacts are acquired through archaeological surveys, testing, and excavations.

LARO's 1958 Museum Prospectus identified the Fort Spokane visitor center as both the repository for the park's artifacts and a place for collection studies. Because the recreation area owned no artifacts at the time, staff recommended contacting various organizations to locate objects considered desirable for exhibit and study purposes. The first priority was objects that would help with the study and interpretation of the area. [55]

Because LARO was not established until after the completion of major archaeological work along the upper Columbia River in 1939-1940, the recreation area had no American Indian artifacts in its museum collection when it turned to the task of planning exhibits in the 1960s. When the interpretive program began in 1962, park staff visited repositories with objects related to the park. These included the Eastern Washington State Historical Society in Spokane, the University of Idaho, and WSU; the last housed artifacts from early 1960s excavations at Fort Spokane. LARO staff believed that the best historic objects were held privately and that eventually they would be donated to the Park Service. Park Naturalist Arthur Hathaway located and obtained many items for the recreation area in the 1960s, but he was unable to obtain funding for storage from the regional office. Instead, he locked some of the items in a jail cell at the Fort Spokane guardhouse and commented, "Now all I have to do is find some help in cataloging the mess." [56]

In 1967, LARO's museum collection consisted of seventy-three catalogued objects related to local history. The artifacts were stored until 1974, when staff began sorting and cataloguing. Most of the historic materials were small metal and stone objects related to the military at Fort Spokane. In 1977, a seasonal museologist completed cataloging the collection, which had grown to 1,077 objects, and designed a display of artifacts in the powder magazine. Four years later, however, some of the accessioned items were removed since they did not fit accessioning criteria. Because a new storage facility was being planned at Fort Spokane, LARO decided that a collection preservation guide would be helpful in planning for long-term conservation and preservation needs. This occurred at a time when Park Service management in general was becoming more supportive of efforts to assess, protect, and care for park museum collections. [57]

To further the effort to bring the park's museum collection management into full compliance, LARO added a new position to Fort Spokane in 1985 that included curatorial responsibilities as a collateral duty; until that time, curation had been a secondary responsibility of the Chief Park Interpreter. The park also built an artifact storage room and work space in the maintenance area of the new Fort Spokane district offices to hold artifacts that were not on display. The LARO collection had been scattered previously throughout the three districts. LARO also shared responsibility with Reclamation for a collection of artifacts from Fort Colvile excavations housed at the University of Idaho, and for a smaller collection from excavations of Fort Spokane grounds housed at WSU. [58]

The Park Service secured additional funding in 1987 to increase its efforts to catalog artifacts and to address concerns about storage and display conditions. At the same time, LARO worked to address collection security through proper storage as well as display conditions (climate control and security) in the Fort Spokane guardhouse. In 1988, contractors completed cataloguing the park's museum collection, which by then had increased to 2,152 items (separate from the much larger archaeological collections). The catalog records were entered on the Automated National Catalog System. [59]

The University of Idaho housed the artifacts and records for the archaeological surveys of Lake Roosevelt done for Reclamation and the Park Service in the 1960s and 1970s. By 1986, the collection totaled close to seven hundred cubic feet, with the Kettle Falls portion alone including about 200,000 American Indian artifacts and 50,000 Euroamerican artifacts. Federal ownership mandated that the repository follow the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for curation. During the mid-1980s, the Colville Confederated Tribes (CCT) requested curation responsibilities for artifacts excavated from Kettle Falls, contingent on completion of a tribal museum planned for the Coulee Dam area. Both the CCT and STI felt strongly that all local Native American artifacts recovered from Reclamation lands should be returned to the tribes. [60]

|

| Archaeologists excavating site of powder magazine at Fort Colvile, May 1970. Photo courtesy of National Park Service, Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area (LARO 3043). |

The Park Service, however, was concerned about any transfer of artifacts to the tribes because it believed that neither the CCT nor STI museum facilities could meet the existing standards. Transfer of Native American artifacts was potentially complicated since many tribes were represented at the Kettle Falls fishery sites and thus would need to be consulted. The Park Service also insisted that any agreement dealing with repatriation of the collection needed to include provisions allowing qualified researchers access to the materials. The agency recommended that all historic artifacts remain government property in a federal repository. Following protracted negotiations between the CCT and Reclamation to transfer the collection, the tribes essentially quit-claimed the historic materials from Fort Colvile to Reclamation for curation at the Park Service facility at Fort Vancouver; the transfer occurred in July 1996. At about the same time, the CCT took over curatorial responsibilities for the rest of the Kettle Falls collection, which remains stored with Reclamation at Coulee Dam until the CCT completes its new repository. [61]

By 1993, LARO curated a museum collection that had grown to include almost fifty-eight hundred archaeological and more than twenty-one hundred historical artifacts; of these, only sixty-eight were displayed in park exhibits. In addition, the park planned to add artifacts from the 1962-1963 excavations, stored at WSU, to the collection. A Collection Storage Plan for LARO, prepared in 1994, recommended enlarging the storage space at Fort Spokane to house the entire collection. This was completed in 1995. The plan also recommended relocating the flammable liquids stored beneath the collection storage room, and this was soon accomplished. In addition, the park installed an environmental monitoring system in the collection storage room. [62]

A Museum Management Plan for LARO, completed in 1997, made recommendations for the museum program for the next five-year period. The report noted the potential for growth in both the archaeological and archival collections and mentioned that the park was not interested in having an on-site natural history collection because good collections were already available at area universities. The fragmentation of responsibilities for cultural resources management between resources management, visitor services, and park management was noted, along with the lack of professional oversight and management of the museum collection. To solve this, the report recommended creating a Branch of Museum Services supervised by a curator, archivist, or librarian. This has not yet been done. [63]

In 1967, LARO had fifty bound volumes, plus a few reports and papers, in its library collection for staff use. The subjects were mostly natural history, with some historical references. Management of the expanding library was simplified in 1989 when all the library books were catalogued in the Park Service regional computerized library system. By 1997, the library had grown to some twenty-eight hundred titles. About that time, LARO awarded a contract to have archivists locate, inventory, accession, and catalog the park's archival materials as a first step in preparing an administrative history of the park. The contractors also listed relevant documents found at other repositories. The 1997 Museum Management Plan provided recommendations on improving access for the staff to the park's information resources. [64]

LARO hired contractors to accession and catalogue some twenty-two hundred historic photographs in 1988 and 1989. These photographs were mostly duplicates from other collections. The slide collection was organized in 1991. Three years later, the park printed positives and negatives for its historic photographs and stored them separately. [65]

Security for the park's museum collection has improved greatly over the years. In the 1970s, the exhibit security alarm at the guardhouse was photoelectric, but it apparently never worked well. After the Park Service revised its security standards for museum collections, LARO assessed its conditions and found that the park needed security and fire alarm systems for the visitor center exhibits and the museum collection storage room at Fort Spokane. Several items were stolen in the 1980s. A security and fire protection survey for Fort Spokane made detailed recommendations for improvement, and the critical elements were implemented within the next few years. Currently, Fort Spokane is protected by a fire detection system and a fire truck on site. [66]

LARO has recently obtained funding to move its artifact collection to better storage facilities available at Nez Perce National Historical Park, approximately a four-hour drive from Lake Roosevelt. The park will retain its archival materials, including photographs. [67]

Compliance Guidelines

In response to the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966 and the subsequent issuance of Executive Order 11593 in May 1971, the Park Service developed protocols for dealing with archaeological and historical sites affected by park development. NPS-28, "Cultural Resources Management Guideline," first published in the early 1970s, directed agency managers to "locate, identify, evaluate, preserve, manage, and interpret qualified cultural resources in every park in such a way that they may be handed on to future generations unimpaired." [68]

In the late 1980s, before the arrival of a park archaeologist, LARO personnel developed special checklists and forms to assess the effect of park actions on cultural resources. The district maintenance foreman, district ranger, chief of maintenance, chief ranger, chief of interpretation, and assistant superintendent all reviewed these forms to see if the proposed undertaking had potential to affect resources eligible for the National Register of Historic Places and thus require compliance with Section 106 of the NHPA. Following the provisions of the Servicewide Programmatic Agreement for complying with Section 106, LARO staff used an Assessment of Effect (106) form to document the park action and the resources involved. Regional cultural resource staff then reviewed these forms and recommended any actions needed to mitigate potential effects on eligible properties. Under the 1991 Programmatic Agreement, proposed actions still were documented on the 106 form and reviewed by the cultural resource staff at the regional office in Seattle. The Regional Director was the responsible official under the implementing regulations for Section 106 until 1995, and the regional cultural resource staff provided recommendations to the Regional Director on the level of effect, mitigation options, and the level of Section 106 review required. After 1995, the Superintendent became the responsible official for Section 106. [69]

Because so many projects involved archaeological clearance, park staff hoped that an on-site park archaeologist would speed clearance, particularly for projects developed with short notice that involved ground disturbance. The first park archaeologist, Paula Hartzell-Scott, was stationed at LARO in 1993 and funded as a term position under the Memorandum of Agreement (MOA) with the BPA. In addition to having field responsibilities for the conduct of inventories completed under the BPA agreement, she also undertook park project clearances. In 1995, Ray DePuydt succeeded Hartzell-Scott in the term archaeologist position. This job has been partially covered under park base funding since 1996, with additional monies from other park funds, soft project money, and regional office funds. The hopes of the park maintenance staff that the park archaeologist would facilitate project clearances have been realized. The archaeologist, however, has suggested that some longer-term coordination and planning would result in better consideration and mitigation of the effects of their projects. [70]

Tribal Interest in LARO's Cultural Resources,

1960s

The CCT and STI expressed their concern with cultural resources when archaeologists began work at LARO in connection with the late 1960s drawdowns. The tribes had been involved decades earlier when Indian crews assisted Ball & Dodd in relocating graves. Interest resurfaced within the STI following the initial survey work in 1966. Archaeologist Larrabee learned that the tribe might be claiming jurisdiction past the water's edge to the center of the Spokane River, potentially impacting archaeological work when normally submerged lands were exposed. Larrabee cautioned Roderick Sprague at WSU to check with the Department of the Interior counsel prior to any salvage work at Mill Creek in the spring. The Regional Solicitor, however, ruled that since the United States bought the lands, the tribe retained no rights below the 1,310 line. In the spring of 1968, STI attorney Robert Dellwo contacted LARO Superintendent Richie after reading about upcoming archaeological work along the river adjoining reservation lands. He noted that while the Tribal Council did not oppose this work, they believed they should be consulted prior to the start of any archaeological project since graves contained tribal ancestors and artifacts belonging to the tribe. Richie apologized for the misunderstanding, explained that the sites were across the river from the reservation, and reassured him that such contracts were awarded only to archaeologists "who have demonstrated competence and a cooperative attitude." He promised to keep the Council informed in the future, and he suggested a possibility of cooperating with the STI on archaeological displays for the new community building. [71]

The tribe took this offer of help on displays beyond what Richie probably intended and requested permission in August 1968 to collect artifacts for the exhibits by digging for bottles at Fort Spokane where many tribal members had worked or attended school. Locating and identifying bottles took special skill, tribal member Glen Galbraith told the Superintendent, and the tribe had "several members well experienced in this regard." In addition to bottles, the STI hoped to gather "truly Indian artifacts" on the reservation side of the lake. Instead of applying directly to the Secretary of the Interior for permission, the STI preferred to work with local LARO officials because of their cooperative attitude. [72] Richie discussed these ideas with Regional Archeologist Paul Schumacher, who responded favorably to the tribe's requests. He promised to tell WSU about their interests and noted that any historic objects would need to go first to the university but then could be loaned back to the tribe. WSU Archaeologist Lester Ross met with the tribal council in November and promised to work on a plan allowing tribal members to survey and map sites on the reservation. In the meantime, he laid out the guidelines that allowed members to collect artifacts as long as they plotted site locations on a master map and labeled artifacts in such a way that they could be tied to specific sites. [73]

Relations with the Tribes, 1970s and

1980s

Relations between the tribes and the Park Service at Lake Roosevelt grew more complicated during the late 1960s, with tensions escalating during the next decade. This was a time of nationwide Indian activism that found local expression in the movement to gain control over Indian lands around the reservoir. Under the 1946 Tri-Party Agreement, the Park Service, as the federal land manager for the Recreation Zone, was assigned primary responsibility over the shore lands, with some restrictions applying to the Indian Zones. This included management and protection of cultural resources on these lands, a responsibility that increased with the new legislative mandates starting in 1966. Both the STI and CCT began to challenge the 1946 agreement in the 1950s and finally achieved a victory in 1974 with a favorable Solicitor's opinion. This caused the Secretary of the Interior to order all parties to negotiate a new agreement that included the tribes. The parties, however, did not reach accord until 1990. During the sixteen years leading up to the new agreement, the tribes pushed for clarification and extension of their rights over a greater portion of the reservoir lands previously controlled by the Park Service. While most of the negotiations dealt with broad legal rights, cultural resources also played into the picture as the tribes asserted their right to control sites they considered a vital part of their heritage.

The question of tribal notification prior to excavations arose again locally in 1972, during the time that it became an issue nationwide. The STI became aware of a promise from Regional Director John Rutter to the Nez Perce Tribe that no archaeological permits would be given for their lands without prior tribal consultation and consent. The STI received assurance that these same procedures would be "uniformly applied throughout the country." This did not extend to non-Indian lands, however, and a federal agency could not be denied a permit. Despite this, the Park Service was notifying archaeologists who worked in the area and was confident that they would be sensitive to the STI request. [74]

Archaeologist Roderick Sprague, who worked on many projects at Lake Roosevelt, addressed similar concerns to his colleagues in a 1974 article in American Antiquity. While acknowledging Indian-archaeologist conflicts during this time of Red Power, he believed that most could have been avoided, and he suggested some ways to establish a cooperative relationship with the tribes. For instance, he considered it "no more than common courtesy" to contact the local tribe or tribes before starting field work, just as providing copies of final reports to tribes was appropriate and professional. He suggested that preferential hiring of tribal members would improve relations and that such cooperative efforts would bring benefits that far outweighed any inconvenience. [75]

Consultations with Tribes

The Park Service formalized the consultation process in September 1987 with the publication of its "Native American Relationships Management Policy" in the Federal Register. This policy directed the agency to develop programs that demonstrated an understanding and respect for the cultural traditions of American Indian tribes that could demonstrate ancestral ties to lands within the National Park System. Park managers needed to establish an effective consulting relationship with affected tribes. The policy was particularly clear with respect to treatment of burials, which were to be located and protected as well as possible. This was hard to apply to Lake Roosevelt, however, where water fluctuations caused annual destruction. In case of disturbance, the Park Service was directed to consult with tribes to determine the most appropriate treatment and disposition, following tribal preferences as much as possible. Additional consultations were to include Park Service archaeologists, followed by the SHPO and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, if needed. This policy was complemented by the passage of NAGPRA in 1990. [76]

Consultations between LARO and the CCT helped determine the appropriate action for preserving a particular pictograph within the park. After monitoring the site for many years, the Park Service brought a conservator in September 1985 to suggest ways to protect and preserve the ancient art. His primary concerns were diverting water runoff and loose gravel from the road away from the rock and keeping the surface free of vegetation. The following June, the CCT reported that the surface had been defaced with some chipping of paint and the addition of graffiti, "MIKE S," in white letters ten inches high. The Park Service, Reclamation, Grant County, and the CCT met in December and decided to redesign the road to pull it away from the site. LARO maintenance crews carefully removed rockfall and built a retaining wall to keep rock from falling on the pictograph in the future. In addition, they installed a system to divert water away from the site. Both actions remain effective in late 2000, supplemented with periodic brush cutting by LARO crews. The Park Service brought the conservator back in September 1989 to remove the graffiti. There has been no further vandalism, and both LARO and the CCT continue to monitor the site. [77]

Burial Recovery, Late 1980s

At Lake Roosevelt, burials became one of the most contentious issues for all parties concerned. During the annual spring drawdowns of the lake, LARO rangers monitored known archaeological sites as time allowed, both to discourage looting and to watch for any human remains that might be exposed. If bones were found, unofficial protocols called for LARO to notify Reclamation, who then contracted with professional archaeologists to excavate the site and analyze the remains, followed by reburial. As early as the mid-1960s, it was apparent that the annual lake fluctuations had a detrimental effect on burials. In the mid-1980s, Reclamation took the lead in the recovery and disposition of burials by proposing funding for a reservoir survey each spring to look for burials and other significant archaeological resources. [78]

The CCT indicated a strong interest in participating in all phases of such a survey and insisted that any plan must have the approval of the tribes. They stressed that burials must be left undisturbed wherever possible, with no excavation done without the CCT's concurrence. After analysis was completed, any artifacts were to be turned over to the tribes for permanent curation. The CCT also requested funds to facilitate tribal participation. Donald Tracy, Grand Coulee Project Manager, responded that Reclamation would monitor areas exposed during the drawdown as usual, assisted by the Park Service outside the Indian Zones, and that all participants would follow steps taken in past years to excavate, analyze, and rebury any human remains found. He welcomed participation from interested tribal members, but he declined to pay for anything more than limited transportation costs for tribal participants. In addition, he stated that while Reclamation was required to consult with tribes and other federal agencies, it could not assign its legal responsibility for the cultural resources to another entity, as suggested by the CCT. "We believe that cooperation and mutual understanding can best be achieved by working within our existing authorities and frequently discussing the issues affecting all parties," he added. [79] Reclamation formally invited both the CCT and STI to participate in the annual spring surveys starting in 1988. The agency still contracted with professional archaeologists from Eastern Washington University, but it worked closely with the tribes in identifying the list of proposed sites and asked for help in identifying next of kin for specific areas. The surveys continued under these guidelines from 1988-1993. High water in 1994 and "jurisdictional confusions" the following year allowed only informal monitoring at a few known sites. Regular spring surveys resumed in 1996. [80]

Changes Under the 1990

Agreement

The three federal agencies (Reclamation, Park Service, and Bureau of Indian Affairs) and two tribes (CCT and STI) had hoped that the years of jurisdictional confusion at Lake Roosevelt would end with the signing of the Cooperative Management (Multi-Party) Agreement in April 1990. The agreement divided Lake Roosevelt and its shore lands into a Reclamation Zone administered by Reclamation, a Recreation Zone administered by the Park Service, and a Reservation Zone administered by the CCT and STI. One area addressed by the agreement was the "Protection and Retention of Historical, Cultural and Archaeological Resources." All five parties agreed to develop a Cultural Resources Management Plan (CRMP) to guide identification and protection of archaeological and historical sites associated with Indian occupation. In addition, the plan was to delineate a procedure for ensuring the return to the tribes of artifacts collected from Lake Roosevelt. The agreement instructed the federal agencies to notify and consult with the tribes before starting any archaeological project involving Indian resources and then went beyond the mere act of consultation to require the agencies to give the tribes a chance to participate in, or even undertake, these activities. [81]

Within a couple of months of signing the new agreement, cultural resource personnel representing all five parties held an informal meeting to discuss their new roles and ways to coordinate cultural resource management at Lake Roosevelt. According to meeting minutes, all agreed that the program should be cooperative and reservoir-wide to provide the best protection for the resources. They proposed setting up a cultural resource advisory board to draft the CRMP required by the agreement. As envisioned, the board would provide technical advice to the agencies and tribes as well as the overall Lake Roosevelt Coordinating Committee (LRCC), but it would not make policy. Both Reclamation and the Park Service asked the LRCC to establish an advisory board to include the five parties along with the Washington State Archaeologist. The LRCC endorsed the establishment of the Lake Roosevelt Cultural Resource Management Advisory Group by June 1991, and asked Lynne MacDonald, Reclamation Regional Archeologist, to serve as convenor. In addition to its general advisory role, the group was to make recommendations about the Programmatic Agreement with the BPA. [82]

Programmatic Agreement of 1991

The Programmatic Agreement (PA) of 1991 introduced a new player into the already complex jurisdictional situation at Lake Roosevelt, and over the next several years it altered relationships among the parties and ultimately changed cultural resource management. The newcomer was the BPA, a federal agency set up in 1937 to market power from federal dams on the Columbia River. Under the Intertie Development Unit environmental impact statement (EIS), BPA addressed only the impacts of its power operations on cultural and natural resources at five reservoirs, including Lake Roosevelt. A subsequent EIS, developed through the Systems Operation Review process, addressed impacts of all operations at fourteen reservoirs, including the initial five. The BPA's responsibility stemmed from its role in power generation at the dams and the associated lake level fluctuations used to meet peak power demand. The frequent raising and lowering of water levels in the reservoirs eroded shorelines and damaged archaeological sites, in addition to having a negative impact on a wide variety of natural resources, particularly fish. [83]

Under the Programmatic Agreement, BPA committed to work with federal agencies and tribes, in their respective jurisdictions, to intensively survey both historic properties and sites with traditional cultural value to Indians. All surveys had to follow accepted archaeological practices. Following the completion of intensive surveys, all parties were supposed to consult with BPA and the SHPO to draft an Action Plan to identify and address issues including research design, determinations of eligibility, methods of mitigating adverse effects on eligible properties, monitoring, and curation. Because the surveys are incomplete, the Action Plan has not been drafted to date. The agreement was signed by BPA in May 1991, with other parties following. [84]