Continuity and Change:

|

|

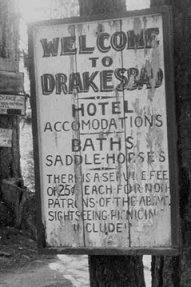

Introduction Objectives of the Research at the Drakesbad Guest Ranch The traditional interest of the archaeologist is the study of the material remains of prehistoric cultures. As a scientific discipline that studies the past, archaeology fundamentally concerns itself with the interrelationships of three dimensions: space, time, and form (Spaulding 1972: 22-39). This is to say that the archaeologist is concerned with the form of human material culture as it changes through time and over space. However, the ultimate objective of archaeological research extends beyond the material remains of past cultures and seeks some understanding of the systemic cultural processes that governed the behavior of the human beings who used the "things" left behind. The term "archaeology" most often raises in the public mind such adventurous images as Heinrich Schliemann digging the remains of Homer's Troy, Howard Carter first peering by flashlight into the tomb of Tutankhamun, Stephens and Catherwood searching the Central American jungle for Maya temples, or Indiana Jones off to a new adventure. The truth of the matter is that archaeology is generally a much more mundane and frequently more tedious discipline, focused most often on the small and generally uninteresting debris of daily life. In recent years archaeologists have more frequently been called away from traditional pursuits and asked to join hands with the historian who has come to appreciate the powerful potential that archaeology has to test of the truth of the historical record, and to recover vital details thought to be too unimportant to place in the written record. It can be argued that what follows here is historical archaeology, of a sort. The subject of the investigation is bounded in space by the Drakesbad valley and its immediate surroundings in Lassen Volcanic National Park, is restricted to the time period between the approximately 1890 and the present, and is focused on the material evidence of continuity and change in the cultural landscape of the Drakesbad valley.

While the traditional archaeologist

studies stylistic change in prehistoric pottery shards to order cultures in

time, it is the photograph that is employed here to establish a time

sequence. Fortunately many of the photographs of Drakesbad are firmly dated

and can be used to form a framework into which

The research presented here also has a practical purpose beyond complimenting the written history of the Drakesbad Guest Ranch. The National Park Service in its vision for the future of the Drakesbad seeks to maintain the facility in close harmony with its past. To this end it is useful to the Park Service to know such unrecorded and tedious minutiae as what type of fences were constructed over the years, how and when paths were lined with stones, if a pond or fountain ever decorated the lawn in front of the lodge, to what extent the meadow was once populated with willows, and so forth. In a more important context, if the Park Service, faced in the 1970s or 80s with the considerable cost of restoring a small cabin attached to the back of a log barn and in a state of near collapse, had possessed clear evidence that this cabin was the oldest standing structure in the valley, perhaps a different decision would have been made. Thus, this research seeks to answer questions about Drakesbad's buildings and environment not fully addressed in the written history with the explicit expectation that such information will assist the National Park Service preserve this unique and beautiful valley as the Sifford family envisioned it, a place close to nature reserved for renewal and reflection. Finally, it is anticipated that this research marks only a beginning and will be refined and expanded as more photographs of Drakesbad are discovered.

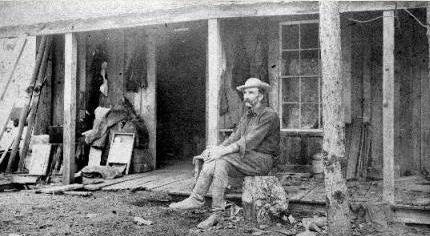

Edward R. Drake and the Settlement of Hot Springs Valley The first person known to have settled in the valley that was later to become Drakesbad was Edward R. Drake (1830-1904). It is possible that Drake may have first arrived in the Drakesbad area as early as 1875. Roy Sifford recalled, "I have been told by others that he was in the valley at Drakesbad when Dr. Harkness, for whom Mt. Harkness was named, was there in 1875" (Roy Sifford interviewed by Les Bodine, 7 July 1987). Sifford also states that before Drake moved further north into Hot Spring Valley he constructed a "squatters cabin" in Warner Valley about a mile south of Lee's Camp where the road crosses "Drake Creek" (Roy Sifford interviewed by Les Bodine, 9 Oct 1987). Records show that in the 1880's Drake purchased a land claim to property in Hot Springs Valley, and over the next decade acquired additional property, the largest parcel obtained through "patents from the United States Government for a total of 320 acres in the areas now called 'Drakesbad' and 'Devils Kitchen'" (Strong:1989:26). By 1900 Drake's land holdings totaled 400 acres and included many hot springs and other thermal features associated with the Mount Lassen volcano.

Roy Sifford described Drake as a trapper and guide who came west from the Rocky Mountains "in the late '60's and '70's, mining up and down the Feather River near Bidwell Bar, [where] he evidently made some kind of a stake. He established a big bar there, and ran it for some time where others have told me that he had employed three or four bartenders, and it was a big place. Then, as the diggings ran out, he moved on up the Feather River into the upper end and into the Prattville — the Big Meadows country. It was there that he came on up into what became Drakesbad, Hot Springs Valley. I think he first came up there in about 1880 or the late '70's. He did not settle the land or anything, but I think he came and went and trapped in there some and made Prattville from about 1875, his winter headquarters" (Roy Sifford interviewed by Les Bodine 5/5/87).

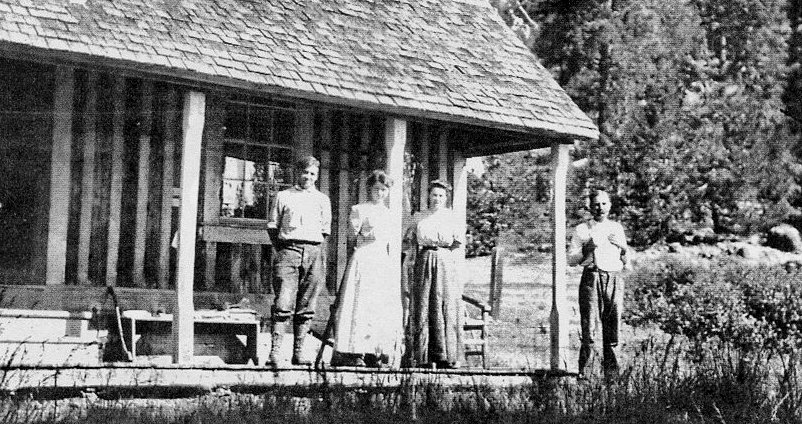

In a letter dated March 27, 1877, to J. Van A. Carter of Fort Bridger, Wyoming, acknowledging the receipt a shipment of moccasins and requesting an additional pair — "the largest pair you have", Drake gives his return mailing address as Prattville, Plumas County, firmly placing him in the Hot Spring Valley area by the spring of 1877 (Original letter in the possession of the author). When Drake settled in Hot Spring Valley he constructed a small log cabin and a barn. Other improvements were pasture fencing of cedar pickets, a bath house, wooden latrines for campers, and a shallow well. In 1890 Drake built "a good new log cabin of some size" at the edge of the valley where today the Drakesbad lodge is located (Roy Sifford interviewed by Les Bodine n.d.). Drake spent his summers in the valley "herding livestock, acting as a guide, and providing limited services to the occasional campers he allowed on his property" (Strong 1989:26). During the harsh Sierra winters the lanky 6' 4" Drake, who is remembered by Roy Sifford as a kindly man and a good fiddler, moved down valley to Prattville in Big Meadows (now under Lake Almanor) "doing odd jobs for a living" (Strong 1989:26). The Sifford Family Comes to the Valley In 1900, Alexander Sifford, an ailing school teacher seeking relief from a troublesome stomach, made the difficult three-day wagon journey with his wife Ida and son Roy (daughter Pearl remained at home with the mumps) from their home in Susanville to Hot Spring Valley to camp and allow Alex to drink the soda waters of "Drake's Spring" (Strong 1989:26). Alex Sifford's visit with Edward Drake appears to have come at an opportune time. Over the course of the three-day visit the older Sifford drank the water and he and the lanky pioneer talked. Drake was seventy and something about Alex Sifford and his family struck a chord in the old man. After a conversation that lasted "long into the night" (Sifford 1994:14) Drake agreed to sell his 400 acres to Sifford for $6,000 (Strong 1989:27). As part of the deal Alex Sifford assured Drake that he would always be welcome to come and go as long as he lived (Sifford 1994:15).

The following morning the Siffords started back to Susanville where Alex obtained a loan for a down payment. On June 20, 1900, the Siffords took possession of Drake's Hot Spring Valley where they would live and work for the next 60 summers. In 1901 Alex Sifford purchased 40 acres in the Boiling Springs Lake area, increasing the total Sifford holdings in the valley to 440 acres. Later in 1908 they renamed the valley "Drakesbad" (Drake's baths) to honor the old pioneer. Life at Drakesbad was hard work for the whole Sifford family, grubbing willows in the meadow, building to improve the property, and providing services to the hundreds of visitors who came to the valley each summer. Making the guest ranch a paying proposition was always a struggle, and the early years were a particularly difficult time of "root hog or die" as Roy Sifford remembers (Roy Sifford interviewed by Les Bodine 7/7/87). However, the Sifford's love of their valley and their willingness to share its beauties never diminished. In no small part the creation in 1916 of Lassen Volcanic National Park resulted from the Sifford's vision for Drakesbad and the Lassen area. It remained an enduring goal of the Siffords, Roy and his father Alex before him, that the Drakesbad valley would some day become part of the Park and open "for any who wished to visit and enjoy" (Sifford 1994:145).

Dates and Place Names: Photographs in this paper are assigned dates only when a date can be determined with confidence. Fortunately, when I sorted through the loose photographs in the Sifford collection, I discovered that Roy Sifford frequently recorded a date either on the back of the of the photograph or on the front in the margin. Many of the photographs in the several Sifford scrapbooks and in Roy Sifford's two-volume written manuscript of "Sixty Years of Siffords at Drakesbad" are also dated, sometimes, however, assigned only to a general time period such as "1920s". Dates for most of the Eastman photographs of Drakesbad were noted on the negative envelope by the photographer and are recorded in the U. C. Davis Eastman Collection database. In a few cases I have assigned a probable time period for a photograph based on elements in the photograph that are clearly visible in a similar dated photograph. Most modern maps of Lassen Volcanic Park show the creek that flows through the Drakesbad valley as "Hot Springs Creek". However, an earlier 1886 geological map and the 1892 Keddie map of Plumas County record the creek as "Hot Spring Creek" and the valley as "Hot Spring Valley". In most of his writing Roy Sifford refers to the creek and the valley using the more historically correct singular form. I follow Sifford here. Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank the following individuals and institutions without whose assistance this research would not have been possible: Peter Schulz whose sense of civil responsibility lured me into the project; Lassen Volcanic National Park Superintendent Marilyn Parris who offered the opportunity, and her Cultural Resource Managers, Karen Haner and Cari Kreshak, who suggested the project and were a source of constant encouragement; Tim Purdy, publisher of "Sixty Years of Siffords at Drakesbad", who patiently and willingly granted me access to the Sifford documents in his care; University California, Davis, Special Collections where I was able to obtain numerous important Eastman photographs; Joan Sayre, Director of the Chester Museum, who granted me access to Roy Sifford's written manuscript; Susan Watson who kindly shared her family scrapbooks; Ed and Billie Fiebiger, the managers of Drakesbad Guest Ranch, who offered insight, suggestions, and lunch; Emily Ortega of Ortega National Parks, who offered server space to host the web site; and Nancy Carruthers Rorty, the gracious lady of Drakesbad who remains an inspiration to us all. Of course, I alone am responsible for omissions or errors in this research, which should be considered as an ongoing project. It is hoped that the many long-time visitors to Drakesbad as they learn of this project will share their personal knowledge to correct, expand, and refine our understanding of Drakesbad's history. This Web edition covers the history up to 2017 and does not include the effects of the 2021 Dixie Fire, which caused extensive damage to the guest lodge (three cabins had to be rebuilt) and the lodge pool had to be removed due to a flood the same year. Tandy Bozeman, PhD

drakesbad/index.htm Last Updated: 09-Dec-2024 |

undated prints can be placed on the basis of structural elements. The study

of this photographic sequence at once yields a clearer view of the history

of Drakesbad than is provided by the written record alone. For example, the

most dramatic event in Drakesbad's history is the well recorded collapse of

the lodge in the winter of 1937-38. The historical record credits the

building's structural failure to inadequate construction methods by the

builder combined with unusually heavy snow loads, but the photographic

record may suggest additional reasons why the building collapsed after

standing firm through 47 winters.

undated prints can be placed on the basis of structural elements. The study

of this photographic sequence at once yields a clearer view of the history

of Drakesbad than is provided by the written record alone. For example, the

most dramatic event in Drakesbad's history is the well recorded collapse of

the lodge in the winter of 1937-38. The historical record credits the

building's structural failure to inadequate construction methods by the

builder combined with unusually heavy snow loads, but the photographic

record may suggest additional reasons why the building collapsed after

standing firm through 47 winters.