|

Lewis and Clark National Historical Park Oregon-Washington |

|

NPS photo | |

"Ocian in view! O! the joy."

When Capt. William Clark wrote these words in his journal on November 7, 1805, he was not standing at the Pacific Ocean but the Columbia River estuary. It would be another couple of weeks before he or Capt. Meriwether Lewis would stand at what they had "been so long anxious to See." By then they had traveled over 4,000 miles across the North American continent with a contingent of 31 explorers, mostly U.S. Army enlisted men, known as the Corps of Discovery.

The expedition was President Thomas Jefferson's idea. He had for years been fascinated by the vast and virtually unknown territory west of the Mississippi River. In June 1803 he announced plans to send an exploratory party by rivers to the Pacific. He chose Lewis to head it, and Lewis selected Clark, his friend and former commanding officer, to share the responsibilities. They were to explore the Missouri River to its source, then establish the most direct water route to the Pacific, making scientific and geographic observations along the way. They were also to learn what they could of Indian tribes they encountered and impress them with the technology and authority of the United States.

The explorers started up the Missouri River from near St. Louis on May 14, 1804. After a tedious journey of five months, they wintered at Fort Mandan, which they built near the Mandan Indian villages 1,600 miles up the Missouri. Here they acquired the interpreting services of Toussaint Charbonneau, a French-Canadian trader, and his young Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, accompanied by their infant son, Jean Baptiste.

In April 1805 the Corps of Discovery left Fort Mandan and followed the Missouri and its upper branches into an unmapped world. Along the Lemhi River, in what is now Idaho, Sacagawea's people provided horses and a guide for the grueling trip over the Continental Divide. In mid-November 1805, after some 600 miles of water travel down the Clearwater, Snake, and Columbia rivers, the Corps of Discovery finally saw the Pacific Ocean after setting up a temporary camp (Station Camp) on a sandy beach on the north shore of the Columbia.

For 10 days the men explored the surrounding area, including Cape Disappointment, looking for a favorable site for a winter encampment. Finally, on November 24, expedition members voted to cross to the south side of the Columbia where game was reported to be plentiful. Lewis and a small party found a "most eligable" site about two miles up the Netul River (now Lewis and Clark River). On December 10, 1805, the men began to build a fort that they named for the local Indian tribe, the Clatsop. By Christmas Day they were under shelter. It would be their home for the next three months.

Treated with "extrodeanary friendship"

When Lewis and Clark reached the northwest tip of what is now Oregon in 1805 they found some 400 Clatsop living on the southern side of the Columbia River. Their neighbors, the Chinook, lived on the northern banks of the Columbia and the Pacific Coast, while the Nehalem lived on the coast to the south. They were all wealthy and shrewd traders, masterful canoe builders, with few enemies, and they treated Lewis and Clark with "extrodeanary friendship."

The captains found them talkative, inquisitive, intelligent, and possessing excellent memories of trading ships visiting the area. Some Clatsops had acquired a few words of English from traders who had visited the area by ship, but communications with them were mainly by gestures. Friendly relations prevailed between the Clatsop and the explorers throughout the winter. When the Corps departed on March 23, 1806, Lewis and Clark gave the fort they had built and its furnishings to the Clatsop leader, Coboway, who "has been much more kind an[d] hospitable to us than any other indian in this neighbourhood."

A "Monstrous Fish"

Two days after Christmas 1805, Clatsop Indians told the Corps of Discovery that a whale had washed ashore southwest of Fort Clatsop near a Tillamook village (in today's Cannon Beach). Adverse weather conditions prevented Clark and other members of the Corps from reaching the whale until January 8. (Sacagawea, who insisted on seeing "that monstrous fish" and the ocean, accompanied them.) By then only the whale's bones remained.

The Tillamook Indians who had gathered much of the whale's meat and blubber were reluctant to part with any of it, but Clark managed to purchase approximately 300 pounds of blubber and a few gallons of rendered oil. Lewis sampled the blubber and found it "not unlike the fat of Poark tho' the texture was more spongey and somewhat coarser. I had a part of it cooked and found it very pallitable and tender, it resembled the beaver or the dog in flavour." Today's six-mile Tillamook Head Trail from Seaside to Indian Beach in Ecola State Park follows the same coastal route used by Clark and his party.

"At this place we had wintered"

The Corps of Discovery remained at Fort Clatsop from December 7, 1805, until March 23, 1806. During that time, Clatsop and Chinook Indians, whom Clark described as close bargainers, came to the fort almost daily to visit and trade. The captains wrote often in their journals of these tribes' appearance, habits, living conditions, lodges, and abilities as hunters and fishermen.

Throughout the winter Lewis and Clark maintained a strict military routine. A sentinel was constantly posted, and at sundown each day the fort was cleared of visitors and the gates locked for the night. Of the 106 days the explorers spent at the fort, it rained every day but 12, and the men suffered from colds, influenza, rheumatism, and other ailments that the captains treated. Clothing rotted, and fleas infested the blankets and hides of the bedding to such a degree that a full night's sleep was often impossible.

With little food in reserve, hunting for meat was all-important. The men killed more than 130 elk, 20 deer, and many small animals, including fowl, during the winter. Whale was later added to their diet. For vegetables the men had to be content with various roots, including the wapato, which resembled a small potato. These root foods were brought by the Indians to the fort for trade.

Due to the rain the men often stayed indoors engaged in a variety of tasks, from servicing their weapons and preparing elkhide clothing for the homeward journey to making elk fat candles as light for journal writing. The captains brought their journals up to date, making copious notes on the plants, fish, and wildlife around Fort Clatsop, and drew excellent sketches. Many such descriptions were the first scientific identification of important flora and fauna of the American West. Clark, the cartographer of the party, spent most of his time refining and updating maps of the country through which they had traveled.

"Excellent, fine, strong & white"

By the time the expedition arrived at the Pacific Coast its supply of salt for preserving and flavoring food was nearly exhausted. To remedy this situation, on December 28 Clark directed three of the men—Joseph Field, William Bratton, and George Gibson—to "proceed to the Ocean [and] at Some Convenient place form a Camp and Commence makeing Salt with 5 of the largest Kittles...." Alexander Willard and Peter Weiser went along to help carry supplies.

The men set up camp about 15 miles southwest of Fort Clatsop "near the houses of some Clatsop & Kilamox [Nehalem] families" in what is now a residential area of Seaside, Ore. Usually at least three men were there, though the number varied and personnel were rotated. Salt was obtained by boiling sea water "day and night" in kettles placed on an oven built of stones and fueled by trees and wood debris along the shore. The men were soon producing about three quarts a day of what Lewis described as "excellent, fine, strong & white" salt. By February 21, 1806, when the camp was abandoned, the salt makers had accumulated enough for the trip home. About three of the approximately four bushels produced at the camp were packed in kegs and used on the homeward journey.

Exploring Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks

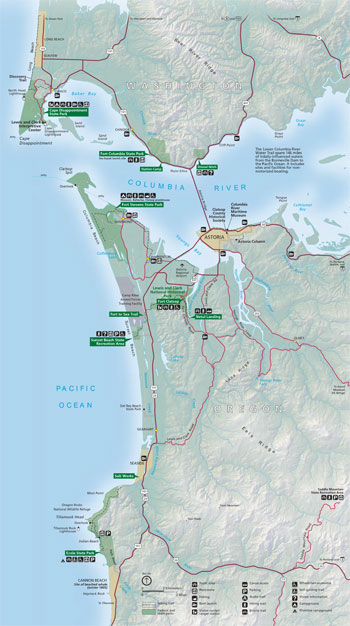

(click for larger map) |

Welcome to one of America's newest national parks. The park rings the mouth of the Columbia River and stretches some 40 miles along the rugged Pacific Coast. The Chinook and Clatsop Indians have made this region their home for thousands of years. More recently, during the winter of 1805-06, Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery visited here at the end of their 4,000-mile trek across the newly acquired Louisiana Territory. Now, with the creation of this new national park, you can walk where first Chinook and Clatsop and then Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery walked.

Lewis and Clark National Historical Park is a joint venture between the National Park Service and the states of Oregon and Washington. The park consists of 12 individual areas that mark the success of key parts of the Corps of Discovery's mission—arriving safely at the Pacific, maintaining friendly relations with local Indian tribes, preparing maps and revising journals that recorded their experiences and discoveries, and preparing for the trip home. Taken together, the following sites embody stories of hardship and danger, of collaboration and adaptation, and of exploration and discovery.

Dismal Nitch So described by Clark, this is the site of the expedition's November 10-15, 1805, encampment. It was here in a cove surrounded by cliffs and high hills that a fierce November storm pinned down the expedition for six days and threatened its survival.

Station Camp Here, during its November 15-25 encampment, the Corps of Discovery got its first view of the Pacific Ocean after 18 arduous months of exploring some of North America's roughest terrain. Here, too. Captains Lewis and Clark polled the members of the Corps of Discovery whether to cross the Columbia River and examine the south side for a winter encampment site. This poll was the first of its kind to include Clark's slave York and Sacagawea.

Netul Landing This area of the park provides an opportunity to stroll a paved path along the Lewis and Clark River (originally the Netul River) and enjoy the river atmosphere. During peak summer months Netul Landing serves as the parking lot and regional transit bus arrival point for a visit to reconstructed Fort Clatsop.

Fort to Sea Trail This 6.5-mile hiking trail from Fort Clatsop to the Pacific Ocean at Sunset Beach approximates the route members of the Corps of Discovery took when traveling to and from the ocean during the winter of 1805-1806.

Salt Works Located in the city of Seaside, Ore., this reconstructed site commemorates the expedition's salt-making activities.

Cape Disappointment State Park This marks the farthest point westward reached by Lewis and Clark. See "Cape Disappointment State Park" for features and activities.

Fort Columbia State Park For thousands of years this area was home to the Chinook Indians. Fort Columbia (1896-1947) is one of the few intact coastal defense sites in the United States. Explore the fort grounds or hike the trails that wind up the hillside through mature stands of spruce and hemlock trees. In summer the park hours are 6:30 a.m. to 9:30 p.m.; in winter 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. A small parking fee is charged.

Fort Stevens State Park For thousands of years the Clatsop Indians lived here on Point Adams, the southern tip of land that marks the entrance to the Columbia River. After this land became part of the United States, the same geography that served the needs of the Clatsop Indians also served the United States military. From the Civil War through the end of World War II, Fort Stevens Military Reservation guarded the mouth of the Columbia River. See "Fort Stevens State Park" for features and activities.

Sunset Beach Recreation Area Sunset Beach is the western trailhead for the Fort To Sea Trail. It provides visitors with direct access to the Pacific Ocean, with expansive views of Cape Disappointment to the north and Ecola State Park to the South.

Fort Clatsop Built on the banks of the Netul River (now the Lewis and Clark River), this was the winter encampment for the Corps of Discovery from December 1805 to March 1806. See "Fort Clatsop" for features and activities.

Ecola State Park In 1806 Captain Clark and 12 expedition members, including Sacagawea, crossed Tillamook Head, which Clark called "the Steepest worst & highest mountain I ever assended," to see a beached whale south of here in the present town of Cannon Beach. See "Ecola State Park" for features and activities.

About Your Visit Start your visit at one of the park's two main visitor centers: at Fort Clatsop, near Astoria, Ore., or the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center at Cape Disappointment State Park near Ilwaco, Wash. The Fort Clatsop Visitor Center is open year-round except December 25. In the peak season (mid-June through Labor Day), park hours are 9 a.m. to 6 p.m.; the rest of the year 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. The Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. A small admission fee is charged at each visitor center. Park rangers are ready to answer your questions and help plan your visit. Maps, guide books, and other literature are available.

For Your Safety: Stay on designated trails and exercise caution at all times when walking or playing around water features. River banks and cliff slopes are often slippery and unstable. On beaches be aware of sneaker waves or drift wood that can knock people down and wash them into deep water.

Cape Disappointment State Park

Cape Disappointment (formerly Fort Canby State Park) is a 1,882-acre camping park on the Long Beach Peninsula, fronted by the Pacific Ocean. The park offers 27 miles of ocean beach, one of the oldest functioning lighthouses on the West Coast, hiking trails, and remnants of Civil War-era Fort Canby. Visitors enjoy beachcombing and exploring the area's rich natural and cultural history. The nearby coastal towns of Ilwaco and Long Beach feature special events and festivals, spring through fall.

Perched on a cliff overlooking the mouth of the Columbia River, the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center contains exhibits offering an overview of the Corps of Discovery's entire journey from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean. Primary focus of the exhibits is on the expedition's discoveries and experiences along the Columbia River, with special attention given to the Corps' arrival at the mouth of the Columbia and the overland journey to the Pacific Ocean. The Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center is open year round.

Fort Stevens State Park

Camping, beachcombing, freshwater lake swimming, trails, wildlife viewing, boat ramps for fishing and canoeing, an historic shipwreck, and an historic military area make Fort Stevens a fascinating park to visit. A network of nine miles of bicycle trails and six miles of hiking trails allow you to explore the park through spruce and hemlock forests, wetlands, dunes, and shore pine. Throughout the year, you can browse through displays dating back to the Civil War at the museum, visit the only enclosed Civil War earthworks site on the West Coast, and explore World War II gun batteries.

The historic area (open daily, 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.; closed Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1) features a military museum and gift shop, guided tours, interpretive displays, movies, living history demonstrations, and a replica of a Clatsop Indian plankhouse (to the west of the World War II barracks). For a detailed tour of the park ask for the Fort Stevens Trail Guide and Historic Military Site at the military museum and gift shop.

Fort Clatsop

Here you will find a replica of Fort Clatsop, as well as living history programs, ranger-led programs, an exhibit hall, orientation films, a bookstore featuring books for all ages, American Indian crafts, and much more. You will also find the trailheads for the Fort to Sea Trail and the Netul River Trail.

The Fort to Sea Trail is 6.5 miles long and runs from the visitor center at Fort Clatsop to Sunset Beach on the Pacific Ocean. Lewis and Clark constantly kept parties in the field hunting, gathering food, making salt, and trading with the Indians. This trail lets you explore the forests, travel along the coastal rivers and lakes, and cross the coastal dunes much like the Corps of Discovery. The trail runs through the homeland of the Clatsop Indians, one of the tribes that helped ensure the survival of the Corps. The Netul River Trail is a shorter trail, only 1.5-miles long, that follows the river from Fort Clatsop to Netul Landing. The landing features a kayak/canoe launch that is part of the Lower Columbia River Water Trail, and a life-sized statue of Sacagawea and her son.

Ecola State Park

Wrapping around Tillamook Head between Seaside and Cannon Beach, Ecola State Park is a hiking and sightseeing mecca. Trails with cliffside viewpoints along nine miles of Pacific Ocean shoreline overlook picture-postcard seascapes, cozy coves, densely forested promontories and even a long-abandoned offshore lighthouse. Swimmers can enjoy two spacious, sandy beaches—Crescent Beach and Indian Beach. Surfers can ride the waves at Indian Beach, and tide pools await discovery. Keep a watchful eye for the many species of wildlife and birds that call Ecola home. During the winter and spring, migrating gray whales may be seen from one of the promontories overlooking the ocean. Those interested in finding the 1806 beached whale site will experience none of the hardship that confronted Captain Clark and his party: a paved road from Cannon Beach and a trail network make the trek much easier.

Ecola State Park offers year-round recreation for all types of modern day explorers.

Source: NPS Brochure (2017)

|

Establishment

Lewis and Clark National Historical Park — October 30, 2004 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

1986 Fort Clatsop Visitor Study CPSU/OSU 87-3 (Marty E. Lee, Donald R. Field and Curt Johnson, 1987)

A Conceptual Plan for the Forest Landscape of Fort Clatsop National Memorial NPS Report CPSU/UW 89-2 (James K. Agee, January 1989)

Administrative History: Fort Clatsop National Memorial (HTML edition) (Kelly Cannon, 1995)

Amphibian Inventory 2002 and 2005, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park: Non-sensitive Version NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR—2015/1028.N (Barbara Samora, Michael Layes and Rebecca Lofgren, September 2015)

An Analysis of Magnetic Gradiometer Surveys at the Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Oregon (John W. Weymouth, January 31, 1997)

An Analysis of Magnetic Surveys at the Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Oregon: The Second Season (John W. Weymouth, January 23, 1998)

Archeological Excavations at Fort Clatsop — Field Notes (Paul J.F. Schumacher, 1961)

Archeological Field Notes, Fort Clatsop, Astoria, Oregon (Paul J.F. Schumacher, January 22, 1957 rev. May 28, 1957)

Arctostaphylos uva-ursi, Bearberry (Cynthia Wright, undated)

Assessment of Coastal Water Resources and Watershed Conditions at Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon and Washington NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRTR—2007/055 (Terrie Klinger, Rachel M. Gregg, Jessi Kershner, Jill Coyle and David Fluharty, September 2007)

"Captain Clark and Party's Journal Over Tillamook Head (Clark's Point of View) to the Site of the Beached Whale at Ecola Creek" (Mary Ann Amacker, August 11, 1974)

Chinook Point And the Story of Fort Columbia (John Hussey, 1957; ©Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission)

Columbia-Pacific National Heritage Area Study (September 2015)

Cultural Landscape Report: Landscape Recommendations 1976-1993, Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Oregon (Marsha R. Tolon, 1993)

Draft Forest Restoration Plan Environmental Assessment, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (August 2007)

Elk: Lewis and Clark, Mount Rainier, Olympic I & M Resource Brief (extract from Vital Signs, 2012)

Elk Monitoring in Lewis and Clark National Historical Park — 2008-2012 Synthesis Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPC/NCCN/NRTR-2014/837 (Paul C. Griffin, Kurt J. Jenkin, Carla Cole, Chris Clatterbuck, John Boetsch and Katherine Beirne, January 2014)

Elk Monitoring Program Annual Report 2010, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR-2012/531 (Carla Cole, Paul Griffin and Kurt Jenkins, January 2012)

Elk Monitoring Protocol for Lewis and Clark National Historical Park — Version 1.0 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR-2011/455 (Paul C. Griffin, Kurt J. Jenkins, John R. Boetsch and Carla Cole, October 2011)

Empires of the Turning Tide: A History of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park and the Columbia-Pacific Region (Douglas Deur, 2016)

Fort Clatsop Small Mammal Inventory, 2001 NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2009/171 (Jim Petterson, February 2009)

Foundation Document, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon (April 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon (January 2015)

Geologic Map of Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (2019)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2019/2023 (John Graham, October 2019)

Immunological Analysis of a Musket Ball from the Fort Clatsop Site, Oregon (Bioarch, Inc., November 6, 1996)

Into the Unknown: The Logistics Preparation of the Lewis and Clark Expedition (©Donald L. Carr, Master's Thesis U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 2003)

Inventory of Fish Species in Lewis and Clark National Historical Park, Oregon (2007) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2008/142 (Samuel J. Brenkman, Stephen C. Corbett and Philip R. Kennedy, December 2008)

Junior Ranger Activity Book: Ages 5-8, Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks (September 2006; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book: Ages 9-12, Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks (September 2006; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Book: Ages 13+, Lewis and Clark National and State Historical Parks (September 2006; for reference purposes only)

Land bird Inventory for Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (2004) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR-2009/165 (Robert L. Wilkerson and Rodney B. Siegel, January 2009)

Landbird Inventory for Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (2006) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCCN/NRTR—2009/166 (Rodney B. Siegel, Robert L. Wilkerson and Robert C. Kuntz II, January 2009)

Location of the William Hampton Smith House and Fort Clatsop (David A. Ek, May 19, 1994)

Long Range Interpretive Plan, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (Ron Thomson, September 2008)

Lower Chinook Ethnobotany: Native Plant Use in a Subsistence Context (Brian F. Harrison, 1989)

Lower Columbia River Lewis and Clark: Sites Boundary Study (HTML edition) Draft (June 2003)

Master Plan for Preservation and Use of Fort Clatsop National Memorial (Burnby M. Bell, July 7, 1961)

Museum Management Plan, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (Robert Applegate, Jonathan Bayless, Barbara Beroza, Blair Davenport and Deborah Wood, 2005)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Fort Clatsop, Salt Works (Paul Northrop and Stephanie Toothman, May 1986)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/LEWI/NRR-2020/2108 (Catherin A. Schwemm, ed., April 2020)

North Coast and Cascades Network Landbird Monitoring Reports

North Coast and Cascades Network Landbird Monitoring: Report for the 2013 field season NPS Natural Resource Data Series. NPS/NCCN/NRDS-2014/691 (Amanda L. Holmgren, Robert L. Wilkerson, Rodney B. Siegel and Patricia J. Happe, August 2014)

North Coast and Cascades Network Landbird Monitoring: Report for the 2015 field season NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR-2016/1128 (Amanda L. Holmgren, Robert L. Wilkerson, Rodney B. Siegel and Jason I. Ransom, June 2016)

North Coast and Cascades Network Landbird Monitoring: Report for the 2019 field season NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR-2020/1284 (Amanda L. Holmgren, Robert L. Wilkerson, Rodney B. Siegel and Jason I. Ransom, July 2020)

North Coast and Cascades Network Landbird Monitoring: Report for the 2020 field season NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR-2021/1337 (Amanda L. Holmgren, Robert L. Wilkerson, Rodney B. Siegel and Jason I. Ransom, November 2021)

Oligohaline Tidal Wetland Plant Community Restoration and Response to Changes in Tidal Flooding and Salinity (Sarah Kidd and Alan Yeakley, 2016)

Plant Associations Known or With Potential to Occur within Ebey's Landing National Historic Reserve, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, Lewis and Clark National Historic Park, San Juan National Historic Park (F. Joseph Rocchio and Rex C. Crawford, March 2009)

Sergeants Charles Floyd and Nathaniel Pryor: Cousins on the Lewis &; Clark Voyage of Discovery (Lawrence R. Reno, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 62 No. 1, January-February 2006; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Station Camp — Middle Village (1991)

Summary Report of the Field and Cartographic Work at Fort Clatsop National Memorial, Astoria, Oregon (Keith Garnett, July 1995)

Suggested Historical Area Report, Fort Clatsop Site, Oregon (HTML edition) (John A. Hussey, April 10, 1957)

The Lewis and Clark Trail from Fort Clatsop to the Clatsop Plains, Oregon (John A. Hussey, August 1958)

Vascular Plant Inventory for Lewis and Clark National Historical Park (Public Version) NPS Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/LEWI/NRTR-2012/603.N (Lindsey Koepke Wise and Jimmy Kagan, July 2012)

Vegetation Classification and Mapping Project Report, Lewis and Clark National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NCCN/NRR-2012/597 (James S. Kagan, Eric M. Nielen, Matthew E. Noone, Jason C. van Warmerdam, Lindsey K. Wise, Gwen Kittel and Catharine Copass, December 2012)

lewi/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025