|

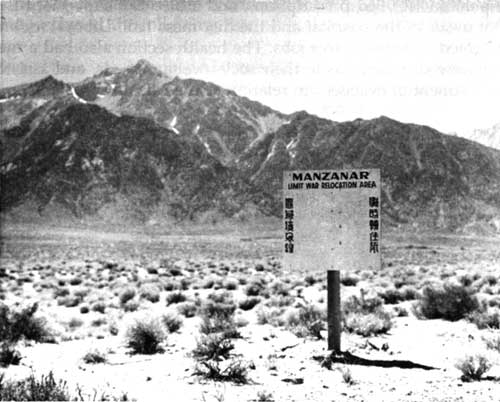

MANZANAR

Historic Resource Study/Special History Study |

|

CHAPTER TEN:

OPERATION OF MANZANAR WAR RELOCATION CENTER MARCH-DECEMBER, 1942

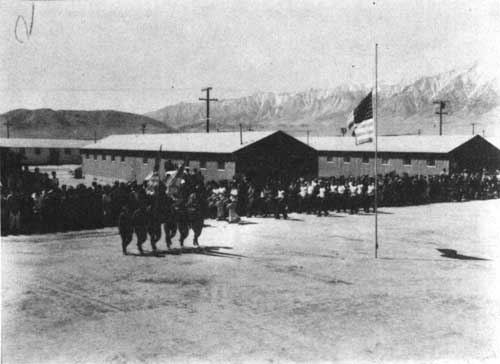

During the period from March 21 to June 1, 1942, Manzanar was administered as an assembly/reception center under the Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCA), the civilian arm of the Western Defense Command. Pursuant to an memorandum of agreement signed on May 17, administration of the Manzanar camp was turned over to the War Relocation Authority (WRA) on June 1. Henceforth, Manzanar would be operated as a war relocation center under the WRA, an independent agency established to administer the ten relocation centers and implement the government's relocation program. During the first six months of WRA administration of the relocation center, the agency attempted to establish a stable working community amid increasing tensions that reached a violent climax in what would become known as the "Manzanar Incident" or "Manzanar Riot" on December 6.

MANZANAR UNDER THE WCCA

Organizational Structure

On March 11, 1942, DeWitt established the Wartime Civil Control Administration as part of the Civil Division of the Western Defense Command to oversee the evacuation of persons of Japanese descent from the west coast and to operate the assembly and reception centers. The WCCA was composed of Army personnel, former Works Projects Administration staff, and Public Health Service personnel (all on loan), as well as other personnel employed directly by the WCCA. The first persons of Japanese descent entered Manzanar on March 21, 1942. These evacuees, commonly known as the volunteer group, were of the opinion that because they had volunteered to help establish the center, certain concessions would be made to them in its operation.

Shortly after its establishment, the WCCA requested Central Administrative Services of the Office for Emergency Management to assume its administrative services. The Central Administrative Services office was located in the Furniture Mart Building in San Francisco. Consequently, it took considerable time for administrative functions at Manzanar to be performed, thus tending to reduce efficiency and foster misunderstanding. To operate the assembly and reception centers under WCCA administration, it was necessary that most of the operational functions be performed by evacuees. Because of the distance between the WCCA main office and Central Administrative Services from Manzanar, numerous administrative decisions were delayed. For instance, it was not until mid-May before evacuees were advised of the salaries they would be paid. Furthermore, the center was in operation for nearly two months before a uniform time keeping system was adopted. As each supervisor had been keeping his own time in his own way, there was considerable dissatisfaction on time reporting. Although the volunteer group went to work in March 1942, no payment for services was made until June 1942.

During the 10-week period that the WCCA operated Manzanar, the camp was operated "by practically two separate and distinct staffs." The first group of administrators, known as appointed personnel, was sent from San Francisco. After a short time, however, the WCCA decided to recruit another group of administrative personnel from southern California to handle the supervisory functions of the center. In addition to this "one practically entire change of personnel," there were continual changes in personnel. Because of the instability in the WCCA staff, few of the appointed personnel were able "to give intelligent answers when questioned by evacuees." Thus, when the WRA assumed control of the center on June 1 it had the formidable task of organizing "a Center rilled with evacuees who had become disillusioned, confused, and incredulous." [1]

Status of Center Operations on June 1

When the WRA assumed administrative control of Manzanar on June 1, George H. Dean, a WRA Senior Information Specialist, visited the center and prepared a report, entitled "Conditions at Manzanar Relocation Area, June 1, I942." This report, which was referred to in Chapter Eight of this study, provides an overall review of Manzanar's administration and operation during its first ten weeks of existence. The report, according to Dean, was "designed to be factual and objective," and there was "no intention of casting reflection or criticism upon any individual or agency." Rather, it was "intended to be a guide post by which we can gauge our own progress in fashioning and operating this community for the best interests of the commonwealth and of the 10,000 Japanese evacuees for whom this will be home for the duration of the war."

Dean observed that evacuee morale "generally speaking, was very good." Among those who were working at occupations for which they had been trained or had a particular aptitude or liking, it was excellent. For those who had not yet found a satisfactory niche for themselves in the camp's activities or occupations for one reason or another, it could be rated as somewhat belter than fair.

With few exceptions, the evacuees, according to Dean, had "shown a strong desire to improve their surroundings to the best of their abilities.

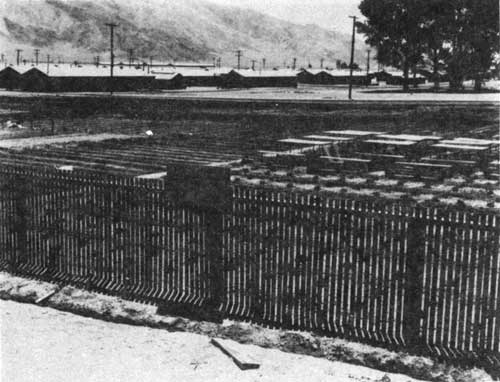

At Manzanar, the WRA, according to Dean, had acquired "a plant consisting of 724 wooden barracks buildings, a hospital group and a children center" to accommodate the total evacuee population of 9,671. In many instances

especially on those days when heavy arrivals of evacuees occurred, assignments to the barracks have been made perhaps inevitably in an indiscriminate manner, resulting in serious overcrowding in some of the buildings. Many cases existed of eight and ten persons of various ages being housed in a single apartment sometimes two and three separate family units. This has resulted in a health and sanitation problem, and in some scattered instances in an unsatisfactory moral problem.

Floors and walls of the barracks reflected considerable deterioration. Linoleum and felt padding had been ordered for installation in the barracks and mess halls, and these materials had been completed in the messes. About three-fourths of the barracks had been supplied with steps before lumber supplies were shut off. There were no partitions in the men's and women's lavatories. Considerable difficulty had developed from sticking plumbing valves. Improper electrical installation and line overloading because of the large usage of electrical devices by the evacuees were creating an extensive number of daily fuse blowouts as well as serious fire hazards in the barracks. The center's fire protection apparatus, however, consisted of one 500-gallon fire engine loaned to the camp by the U.S. Forest Service.

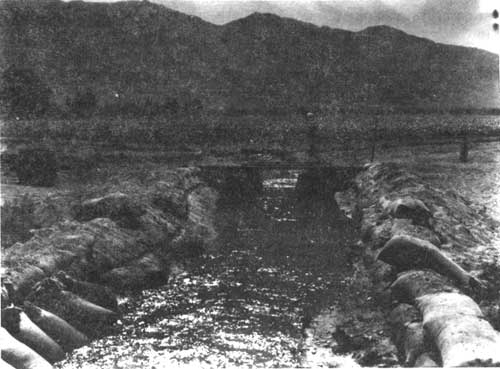

The center's water supply system was not completed. Tests conducted in May had revealed a "rather high degree of pollution and a trace of E. coli." There had "been a comparatively high incidence of dysentery within the project," and studies were underway "to determine whether this was attributable to pollution of the water supply." Dishwashing equipment was "inadequate and unsanitary," and because of an inadequate supply of hot water, the "dishwashing situation" was considered to be the "most serious health menace in the project" by the chief of the "5th Public Health District." New dishwashing equipment had been ordered, and its installation was underway on June 1.

Sewage was siphoned from the camp under the Los Angeles Aqueduct east of the camp and spread over open land, pending completion of a disposal plant. Sectional drainage problems existed, and water was collecting under some of the barracks. Garbage was "dumped in an open pit east of the project, burned and buried." No attempt was "made to use the wet garbage but plans were being drawn for hog and chicken projects to utilize this waste." Paper was "baled for future sale." Tin cans were "segregated, some being used in handicraft and plant propagation projects."

In all phases of the project, Dean reported that there "existed a serious shortage of equipment." Equipment shortages included

the mess halls, the farm and other project operations. In preparing 100 acres of land for cultivation only one plow was available and it was necessary for the evacuees to work three shifts in order to make maximum use of the limited equipment, and to supplement this with a high proportion of hand tilling, to get the planting done before too late in this comparatively short growing season.

Prior to June 1, little landscaping work had been accomplished with the exception of "a limited, voluntary improvised project in front of the guayule experiment and plant propagation stations." The absence of landscaping was due to the lack of both equipment and stock. In this respect, according to Dean, the project was

substantially as it was when the land first was cleared of the native sagebrush growth. Neither had steps been taken looking towards dust palliation. The project possessed no sprinkler wagon and a limited amount of hosing was done by hand. With the destruction of the natural ground cover, the dust problem is acute on windy days. Plans have been drawn for the restoration of the ground cover with alfalfa and other grasses.

Of the 9,671 evacuees at Manzanar on June 1, nearly one-third (3,165) were employed in "operations, services and functions within the project." About 125 were employed in agriculture, while only seven were involved in "industrial projects, with the exception of the staff in the economics planning section."

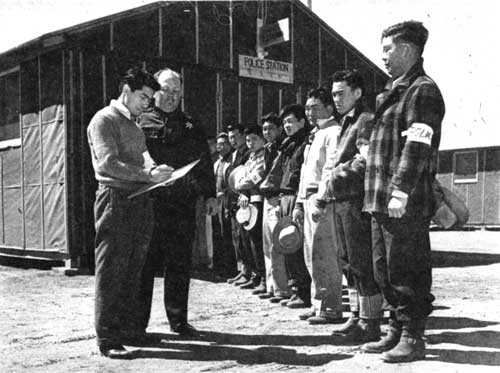

The "great bulk of the project employment was in community services" which were "being handled on June 1 by an all-Japanese corps working under J. Mervyn Kidwell." Incoming inductees were met "by members of the Volunteer Service Corps who escorted them to their barracks and informed them of the essential facts regarding the camp." Recent "arrivals of evacuees" had been handled smoothly and with little confusion, "though earlier inductions left much to be desired."

Residents of the center were kept informed of announcements "by bulletins posted on boards in each block and each mess hall," and published in the Manzanar Free Press, a six-page mimeographed camp newspaper issued tri-weekly. Bulletins, all signed by the project director or assistant director, were posted both in English and Japanese.

All "inquiries, complaints and suggestions" were made to a "Japanese-staffed information department." This staff held daily morning conferences to handle "simple" matters, while "policy" matters were referred to the project director who attempted to settle all questions promptly. Complaints were made by the camp residents to the Japanese information service, and verbatim copies were made and transmitted to the proper project section. The information service also took care of personal matters for the evacuees, such as writing letters, aiding them in filling out forms, selective service questionnaires, and other documents. This service maintained a principal office and five sub-offices throughout the camp.

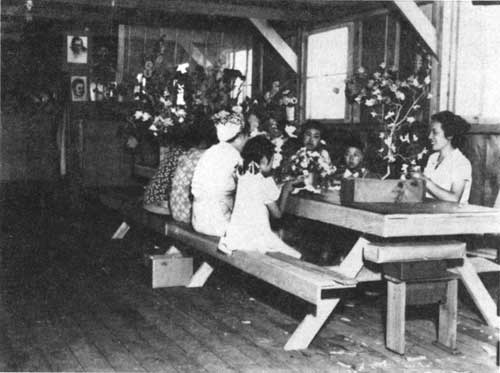

Recreational activities were conducted "under severe shortages in equipment." No funds had been "expended up to June 1 for the purchase of athletic or other equipment," and activities "were conducted with facilities which had been donated to the project or had been provided by the evacuees themselves." Although there was "no dearth of desire to participate in athletics, arts and crafts, music, dancing and other such pursuits" among the evacuees, the "limitation was the absence of sufficient means to keep them engaged."

Japanese arts and crafts instructors worked with their own tools and material and in some instances furnished them to their pupils. The baseball and volleyball equipment in the camp was donated, as were the equipment and toys for the nursery schools. Simple toys, small benches, and tables were made from scraps of wood gathered around the newly-erected barracks. Definite locations for softball and baseball diamonds were impossible to establish. They had been laid out in the firebreaks, but had to be moved frequently just ahead of farm or maintenance equipment which had come to level and prepare the ground for planting. Notwithstanding these obstacles, the evacuees quickly organized a variety of recreational activities.

The overcrowded conditions existing "in a large number of the barracks had fostered many problems in family relationships," which, according to Dean, were "being handled by a Japanese evacuee, Mrs. Kikuchi." Juvenile situations, however, "were comparatively few and most of the cases coming to the attention of Mrs. Kikuchi involved child disobedience and recalcitrance apparently arising out of the changed surroundings, the lack of education facilities to occupy them and the heterogeneous composition of the people residing in the same apartments."

Self government by the evacuees at Manzanar was, according to Dean, "little more than an embryonic state." Block leaders had been elected, and they had organized a project council which, in turn, had elected its officers. A constitution for community government was being prepared, but no evacuee-conducted judicial system had been established to deal with "offenses of a comparatively minor character."

Dean observed that Manzanar housed "an undetermined number of professional and other gamblers." Fifteen evacuees were arrested and pleaded guilty on June 1 before Justice of the Peace C. H. Olds of Inyo County Township who held court in the center's police building. Olds had been brought from Lone Pine "in the absence of any internal judicial setup in the project." This development was the "only instance since the opening of the camp in which evacuees were involved in an offense sufficiently serious to justify the services of a civilian justice." Each of the 15 evacuees was fined $25 and sentenced to 30 days in the county jail. All but $5 of each fine was suspended, subject to good behavior. Olds indicated that his lenience was due to the fact that it was the defendants' first offense, but he warned that in the future punishment would be more severe. According to Dean, no "liquor nor narcotics have been in evidence in the area."

Considerable criticism, according to Dean, had been voiced by evacuees relating to the "procedure followed in permitting evacuees to receive visitors." Outside visitors, mostly white, were allowed by the WCCA to "see the Japanese only on Saturday afternoons and Sundays and then in the police headquarters in the presence of a police officer." On June 1 the WRA issued new visitation policies "permitting the evacuees to receive visitors in their quarters, after automobiles are parked in the police area."

In response to evacuee complaints that they had been "separated from their furniture and other family possessions," the WRA promptly asked evacuees to prepare inventories of their belongings and conducted a survey to determine the amount of warehouse space available. Of the 40 warehouses constructed at Manzanar, eight or nine were available for this purpose. Many of the warehouses, however, were not being utilized to their fullest capacity "because of the danger of overloading the flooring and causing it to collapse."

Dean observed that the WCCA's "evacuation and resettlement program" did not provide for the inauguration "of a full education program for the Japanese until this autumn." Although no "regular" schools were in operation on June 1, classes in English and in arts and crafts and music were underway. Americanization classes had been organized with an enrollment of about 250 aliens.

Dean noted that under the WCCA, passes to outsiders for admittance to the camp were handled by both the police department and the project director. When the WRA assumed control of the camp, however, orders were issued immediately that all passes must be signed by the director. All passes issued to Japanese on errands outside the camp were signed by the project director and the Japanese were required at all times to be accompanied by a Caucasian.

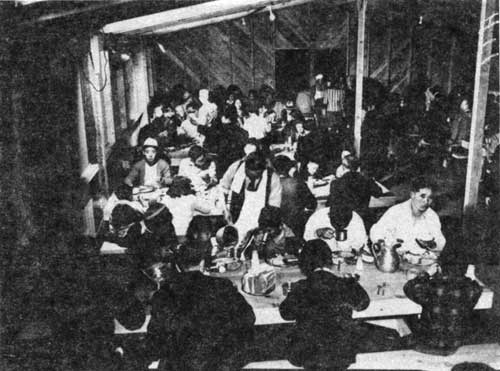

Twenty mess halls were in operation on June 1, each accommodating approximately 500 persons. Sixteen additional mess halls, although constructed, were inoperative because of the lack of plumbing facilities and mess equipment. Messes had not been built for the hospital or appointed personnel.

Dean found the rate of flow of supplies from the warehouses to the mess halls was satisfactory, the menus adequate, and the food well prepared. Food and other supplies, however, were frequently "issued from the warehouses without proper requisitions resulting in a large amount of confusion in accounting and inventories."

Because of the sixteen inoperative mess halls, there was "considerable overloading of the messes" in operation. It was necessary for the evacuees to stand in line for 20-45 minutes in temperatures averaging around 90 degrees. Thus, the WRA immediately took steps "to evolve a staggered system of meal hours until such time as the additional mess halls can be opened."

Dean reported that there was no system of identification in effect which would require persons to take their meals in the mess hall in their particular blocks. Menus in the operating mess halls were not standardized. Thus, there was a "considerable 'shopping around' for the mess hall that served the meal most to their liking, resulting in overcrowding of some messes and slight underloading in others." There were numerous cases "of persons doubling up on their meals from one mess hall to another, particularly at breakfast."

Different menus were in effect for the appointed personnel's "Mess No. 1." This mess "was obviously much better than the menus served to the evacuees," resulting in "considerable dissatisfaction on the part of the Japanese who observed the fact or were informed of it by the white personnel." Steaks and other elaborate dishes were served at a cost of 25 cents per meal. Accordingly, the WRA took immediate steps to standardize the mess menus "between the Japanese and the staff personnel."

Dishes, utensils, and cooking equipment were in short supply. Table service was generally satisfactory, although "greatly overstaffed." There were an insufficient number of sinks and occasional shortages of hot water. Two more sinks were necessary in each mess hall for the proper disposition of dishwater. Careless disposal of dishwater resulted in an unsanitary condition in the vicinity of the mess kitchens.

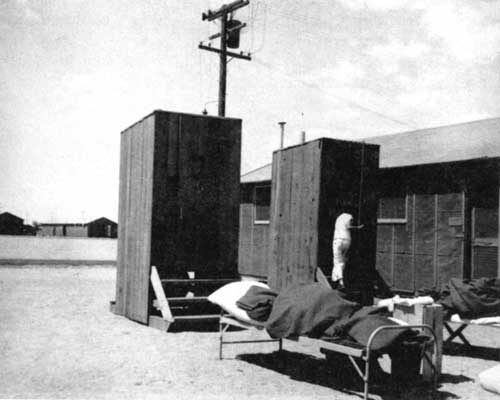

On June 1 the hospital facilities at Manzanar consisted of a "10-bed improvised hospital in one of the barracks buildings, an isolation ward, an out-patients' clinic and a children's ward." Ninety-two patients were hospitalized. Of these, there were 42 cases of "uncomplicated measles," three cases of "German measles," and nine cases of "chickenpox." Under normal circumstances and with proper residential facilities, these cases "might have been treated outside a hospital." The other 38 cases "in the professional judgment of Dr. James M. Goto, chief of the medical staff, hospitalization was absolutely necessary."

Syphilis and tuberculosis "were known to exist among the evacuees, probably in about the same proportion as among the general Japanese population." No personnel with sufficient training, however, were available to conduct a comprehensive survey. No syphilis nor typhoid tests had been given to any of the persons employed in the mess halls. Immunization of all evacuees for smallpox had been nearly completed by June 1, but diphtheria immunization had just begun and no vaccine for whooping cough, which was "quite prevalent" in the camp, had been received. Immunization for other communicable diseases was not contemplated because of the lack of sufficient staff and facilities.

Respiratory ailments "showed a tendency to spread among families housed in overcrowded apartments." In some instances, "where eight or ten persons" had been housed in the same unit, "severe respiratory diseases" had "afflicted as high as five or six members of the family."

Manzanar did not have a trained dietician or sanitarian as of June 1, although several students had received some training and were acting as "sanitary inspectors under the direction of Dr. Togasaki." Prenatal and post-natal work was carried on by the hospital staff, and formula and immunization was provided for babies under two years of age and special diets for children under five years.

"A rather high incidence of athlete's foot existed" at Manzanar, the source of "infection apparently being in the shower rooms." Dysentery "was occurring at a sufficiently high rate to indicate there was some contamination of the water supply." Investigations by the state health department indicated the "probability the contamination occurred east of the intake." The water supply line traversed "an area through which pass bands of sheep on their way to the mountains." A chlorinator had been installed prior to June 1, but it apparently had not been in constant operation.

Since its opening, Manzanar had "had three deaths." The deaths included "one from advanced tuberculosis, one from a heart attack probably attributable to the altitude, and a third from a kidney ailment of long standing." This number was "considered low for a community of this size."

According to Dean, approximately 100 acres had been prepared for cultivation and about 75 acres had been planted "to diversified vegetable crops, including fifteen acres of tomatoes." "Crops on sixteen acres were above ground." Some 125 Japanese were employed in the plowing and planting, working three shifts a day with a single Fordson tractor and plow." "About 1,000 fruit-trees, mostly apple and pear, which were on the property when it was taken over by the government" were "being revived and will bear some fruit this fall, though they had not been watered for nearly fifteen years except by the ordinarily scant precipitation of the area."

A propagating nursery was in operation at Manzanar, "chiefly with plantings from native seeds, and seeds brought into the relocation center by the evacuees themselves." Seeds for landscaping stock were on order. [2]

MANZANAR UNDER THE WRA

Organizational Structure

The War Relocation Authority assumed full administrative responsibility for the Manzanar War Relocation Center on June 1, 1942, with a skeleton staff, consisting only of a project director, assistant project director, administrative officer, supply and transportation officer, procurement officer, and telephone operator. At that date, the WRA had not made a decision as to what staff was necessary for the operation of the center. Thus, the WCCA agreed to leave some of its employees at Manzanar until June 15 to permit the WRA time to determine its administrative needs and recruit a staff.

On June 1 there were approximately 55 WCCA employees at Manzanar, most of whom had come from the Works Projects Administration. Twenty-five were temporary as work foremen (6), Caucasian police (10), Caucasian firemen (4), and truck drivers (5). Of the remaining 30, Nash recommended the employment of 14, five of which were approved by the WRA office in San Francisco by June 6. [3]

On June 6 a master chart for the administrative organization each of the relocation centers was issued by the WRA. This chart provided for a project director as the chief administrative officer of each center. He was assisted by an assistant project director who had direct supervision of the transportation and supply, maintenance and operations, employment and housing, and administrative divisions. The transportation and supply division included motor pool, mess management, and warehousing sections. [4] The maintenance and operations division included building and grounds maintenance and garage sections. The employment and housing division supervised the occupational coding and records, quarters, and placement sections. The administrative division included procurement, property control, personnel records, office services, and budget and finance (cost accounting, fiscal accounting, and audit units) sections. [5]

This organizational chart remained in operation until October 1, 1942, when an agency reorganization plan was implemented. At that time three divisions at each center — employment and housing, transportation and supply, and administration — were placed under the supervision of the assistant project director. The maintenance and operation section was discarded and the motor pool, warehousing, equipment maintenance, and moss operation units were placed under transportation and supply. The building and grounds maintenance section was transferred to the public works division which was under the direct supervision of the project director. This organization remained in effect until December 15 when the entire staff at Manzanar would be reorganized in the wake of the "Manzanar Riot." [6]

Appointed Personnel

The WRA encountered serious problems in recruiting administrative staff for Manzanar throughout 1942. Aside from an acute manpower shortage on the west coast during the war, other contributing factors included: (1) higher rates of pay, plus overtime and double-time, in west coast war-related industries; (2) isolation of the project; (3) adverse climate; (4) temporary nature of employment (Many felt that project would close long before it did); and (5) the fact that some people did not wish to work with persons of Japanese ancestry.

Staff recruitment at Manzanar "was made extremely difficult" since prospective employees had to be approved by the 12th Civil Service District that administered the entire west coast. The center was from two to three days by mail service from the San Francisco office of the Civil Service Commission, making it virtually impossible to obtain approval of an assignment in less than one week. The Civil Service Commission offered Manzanar its cooperation, but it often did not have applicants interested in working at Manzanar.

Thus, the burden of recruitment was left largely to center management. Recruitment of Manzanar staff was conducted by the assistant project director through personal contacts, by the personnel officer through contacts principally in Los Angeles, and by soliciting the cooperation of project staff members who referred to the personnel management section persons they could interest in employment at the center.

Despite these problems, the WRA recruited a total of 229 employees during 1942. Of this number, 209 were new employees and 20 were transferred from other government agencies. The staff at Manzanar averaged about 200 during its first six months under the WRA.

At the time of their appointment new employees were given considerable information on the purpose and philosophy of the WRA. However, there was never time or sufficient personnel staff to arrange for more than one such conference with each new employee "to learn how they were adjusting to their assignments and their new surroundings, and whether they were properly placed."

Recruitment for various positions was difficult because salaries established by the organizational chart in accordance with Civil Service classification procedures were inadequate when compared with salaries being paid for similar work on the west coast. This problem was illustrated by the position of elementary teacher. In an attempt to staff the elementary school, Manzanar camp administrators wrote letters to every known teacher placement bureau in the United States. The majority of the elementary teaching staff was recruited from the South and Middle West where the salary scales were less than that established on the Manzanar organizational chart. Most of these teachers, however, taught for only several months at Manzanar and then transferred to public school systems in California where the pay scale and living conditions were more attractive.

Housing for appointed personnel also posed a problem for recruitment and retention at Manzanar during 1942. On August, housing quarters for administrative staff at Manzanar consisted of nine housekeeping apartments and 16 bachelor quarters. The latter were adequate for two single employees each. It was obvious that the quarters provided were not sufficient for a staff of approximately 200 people. The problem was met during 1942 by the decision to house employees and their families in the evacuee barracks, thus exacerbating the already overcrowded housing conditions in the camp. Families of three or more persons were assigned to two-bedroom apartments, while two-person families received one-bedroom apartments. Single women were housed in dormitories, and single men in bachelor quarters two to an apartment. The only exceptions were for single section heads who received one-bedroom apartments and single employees who secured medical certificates from the Principal Medical Officer showing that they required diets different from those served in the administrative mess. The latter were assigned to one-bedroom apartments with the understanding that each share the same with another single person.

Another problem that hindered recruitment and retention of appointed personnel was related to the issue of recreation at Manzanar. The camp was located 5 miles from Independence and 12 miles from Lone Pine. Those employees who had their own transportation, even with gas rationing, had access to various forms of recreation in these small towns. However, many employees had no means of transportation, and no recreational facilities were available to them, thus contributing to their sense of isolation and low morale. [7]

New Manzanar Administrator

On May 20, 1942, Roy Nash, former superintendent of a large Indian agency in California, arrived at Manzanar to assume the office of Project Director for the War Relocation Authority, replacing Clayton E. Triggs, the former WPA administrator who had served in that position under the WCCA since inception of the camp in March. This change of administration, while the camp was still being constructed and evacuee contingents were still arriving, was, according to the "Project Director's Report" in the Final Report, Manzanar, prepared by Brown and Merritt, "a confusing time to 'switch horses.'" The evacuees, beset by scores of petty, as well as fundamental, problems and worries, and the camp management struggling to help resolve those problems and cope with administrative issues, were "just beginning to understand one another and to understand a few things which should be done to put the machinery of management in high gear."

The War Relocation Authority brought in new organizational ideas and new managers who, according to Brown and Merritt, had "no knowledge of the road already traveled." Although not the "best strategy," this operational methodology was "understandable when one remembers WRA set up new centers, ready for occupancy, and staffed before any evacuees were sent there, in all instances except Manzanar." While the WRA had "a new start with each other group of people," at Manzanar it "took over a going institution, stopped most of the wheels at one stroke, and started off on a new track." The abrupt change in camp administration would have repercussions for both camp management and the evacuee population during the coming months. [8]

Only six persons in supervisory or managerial capacity were carried over from the WCCA management to the WRA management. The WCCA managers who were replaced were generally bitter about being terminated, and they spread rumors about the WRA in nearby Owens Valley towns. The rumors left the impression that the WCCA, as a result of its connection to the Army, knew how to handle "Japs," but the WRA was a "social welfare outfit who will coddle 'em'." Before leaving Manzanar, some of the outgoing WCCA employees destroyed "valuable records" and sowed seeds of dissension, stirring up their evacuee assistants and helpers by spreading other rumors — "especially one they would not get paid by WRA for what they had done." According to Brown and Merritt, the WCCA employees "left the place in a bad state of confusion." [9]

According to Brown and Merritt, the decision by Nash to remove virtually all WCCA employees, even though there were no immediate replacements, was indicative of his "determination and ability to make quick decisions." Nash, a dynamic personality, had a "tendency to make fast decisions" and a determination "to carry these out in the face of any amount of difficulty." Some of his decisions "were faulty and some excellent," but "no course could be charted by any regularity of goodness or badness from that time out." Two other developments early in Nash's tenure as Project Director illustrated his tendency to make snap decisions that would have repercussions for camp operations during the ensuing months. [10]

In his first public address, Nash informed the evacuees at Manzanar that they could take advantage of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, some ten miles west of the center. This statement was received "with loud cheers by the evacuees who had their eyes on the streams and lakes of the region," but it was also received "with loud cries of protest by the local people who feared more than anything lax control by the new management." Individuals and organizations immediately telegraphed DeWitt and the Western Defense Command, and "a reprimand came flying back to the new Director — who had acted in good faith, but blindly — which made him countermand his order of allowing visits to the mountains." Describing the impact of this matter on the evacuee population, Brown and Merritt observed:

Although many of the residents understood the situation, still it was a bad start for the new management. To have the green fields of heaven thrown open with unrestricted invitation on one week, and then to have these same fields barred forever the next week was a bitter pill to swallow . . . and even those who understood were heard to mutter,' I wonder if it was done on purpose?" [11]

According to Brown and Merritt, the rumor started by the fired WCCA employees on wages began "to bear fruit shortly after the new management took over." Many evacuees had money in savings accounts, but they were running out of available cash needed to purchase "simple incidentals." Some who had lost most of their possessions in the evacuation, such as those from Terminal Island, were "in acute need for simple necessities such as toothpaste, soap, tobacco, and cosmetics." The lack-of-pay rumor, starting first as a whispering campaign but later growing to a rumbling storm, disturbed the new WRA administrators. As continuing discussions at the highest levels of the federal government resulted in no immediate solution to the amount and method of pay checks for the evacuees, Nash "on his own responsibility made an agreement with the Canteen to honor script to the extent of five dollars per person, the script to be redeemed later when these persons received their first pay checks." Nash immediately had "five-dollar script coupons printed in the local printing establishment and 'paid' all workers the five dollars on account," thus temporarily relieving tensions and placing the "new management back in the confidence of the people." [12]

Deteriorating Morale and Public Relations at Manzanar

On June 6 to 8, at the end of the first week of the WRA's operation of the Manzanar camp, Colonel C. F. Cress, deputy director of the WRA, visited the relocation center to observe its operation and gain firsthand knowledge about the progress of the WRA takeover of the camp. Although he felt that the WRA was making "satisfactory progress," he was concerned about the deteriorating morale both in the camp and the surrounding region. He observed:

that the situation in the Owens Valley Area may suddenly become very unsatisfactory or even dangerous, due to the attitudes of individuals of any one of four groups. These groups are: The civilian residents of Owens Valley, the disgruntled discharged employees of WPA still in the Valley, the employees of WRA and the Japanese themselves. In my opinion, words alone can do immeasurable damage at this time.

Cress observed that the Owens Valley residents felt

that the Federal representatives have not kept their promises that the Relocation Center should cause no additional expense to Inyo County and that the Japanese would be kept under close guard and thus cause little inconvenience to the local inhabitants. In this connection Congressman Leland Ford emphasized to his constituents during his visit on May 5th that the agreement between Congress and the War Department called for 50 Caucasian civilians to be kept as internal police and for a close guard of the Japanese at all times.

According to Cress, the Owens Valley residents also maintained

more than a slight interest in the WPA project personnel who have lived among them for over three months. When WRA assumed control at Manzanar and discharged certain WPA employees, the local paper charged politics. However, the Editor's definition of politics was - the running in of a new gang while using the Civil Service gag and the cut in salary racket to force efficient WPA employees out. This feeling was intensified by the fact that the local residents have strong prejudices against Bureau of Indian Affairs personnel.

At this time the policy of our organization with reference to Owens Valley people should be close mouths and no speeches or loose promises. We should also seek to have WCCA formally declare the Manzanar relocation area a military area and to work out, ourselves, some procedure whereby the expenses to Inyo County will be minimized and the possibility of Japanese voting in this county eliminated.

Cress also commented on the disruptive influence of some discharged WCCA employees that were still in Owens Valley. He noted that some

of them are bitter over the loss of their jobs and have expressed their feelings to both the local residents and the Japanese. They are the potential interpreters of any loose talk by WRA employees, or any untoward incidents.

Cress also described the problems caused by the new WRA employees and managers at Manzanar during the first week of the WRA's administration of the camp. He stated:

Our own WRA employees at Manzanar are not yet an integrated group. Our greatest weakness is a lack of procedures and policies and a tendency to make changes rapidly. There are leaks in our organization. I felt that some of our employees still have a paternalistic attitude rather than the idea of helping the Japanese help themselves. However, this idea is not shared by the Project Director.

One incident, according to Cress, had caused "considerable confusion related to project area restrictions." Echoing the aforementioned observations by Brown and Merritt, Cress noted:

. . . On May 17th at public meeting of the Japanese in Manzanar, Mr. Triggs and Mr. Nash made speeches. Mr. Triggs announced that WRA would make some relaxation of the confining restrictions on the Japanese. Mr. Nash then told the crowd that Colonel Magill, Provost Marshall, Fourth Army, had agreed that there would be a freeing of the limits; that a fence would be erected along the front of the relocation area and half way along each side and that the back area would be left open, although patrolled by military police, so that the Japanese would be free to wander from camp to the mountains if they desired. The following Sunday some of the Japanese went out of camp toward the mountains and were brought back by the military guards. Either the Japanese misunderstood or they were trying out the management. Shortly before, a military police guard had shot a Japanese who attempted to pass beyond the camp limits and who failed to obey his order to halt. These two incidents alarmed the residents of Owens Valley and caused considerable repercussions among the Japanese.

Cress also noted that the Japanese evacuees had been "disturbed by the situation," observing that they "do not understand why the management of their camp was changed, nor why their Caucasian friends were fired." The urgent needs of the evacuees were "relief from the present overcrowding in quarters and the materials to fix up their homes." In addition to these tensions, there was general alarm in the camp because of the "possibilities of an epidemic" "when the fly and mosquito period begins."

Cress sensed that "we have a number of Japanese evacuees sniping at us." This sniping could "easily be turned into active opposition and into positive acts, if we provoke it." On the other hand, the "bulk of the evacuees want their problem of satisfactory living to be solved and will welcome constructive action."

Cress was "convinced if WRA stops talking and gives the Japanese a chance to help themselves, the situation will be solved." However, he was "also satisfied that all of the explosive elements are present in Owens Valley for real trouble." Policy changes "must be placed into effect slowly and with due regard to the public reaction of the various groups concerned." [13]

Brown and Merritt also discussed the declining morale in the camp and its deteriorating public relations in Owens Valley in their "Project Director's Report" in the Final Report, Manzanar. According to their assessment, much of the goodwill in Owens Valley communities that had been developed by Triggs during March and April 1942 was dissipated during the early weeks of WRA management as a result of "the failure on the part of the Project Director to understand the position of the local people." During his first week of administration, Nash had a brief visit with Merritt chairman of the Citizen's Committee, but he had no further contacts with that organization. Several months later, after public relations with the valley towns "were completely severed," he asked the committee to meet. When the members "pointed out the true state of affairs and suggested the Committee disband," Nash "was in hearty accord with the decision."

In an effort to restore outside community and camp management relationships, Brown arranged for Nash to speak at several luncheon clubs. The speeches, however, only served to antagonize the communities because the general theme of the talks was that "Most of these people are American citizens and are entitled to all the rights you enjoy, but other American citizens, including you people, want to deny them these rights."

Public relations with Owens Valley communities, according to Brown and Merritt, reached rock-bottom after two incidents which received considerable publicity in the local press. Nash authorized the Chief of Community Services to take a number of evacuees up one of the canyons west of the camp for a picnic. The group was eating lunch on the porch of a cabin owned by a local man who arrived unexpectedly to find it "swarming," to use his words, "with Japs." Later Nash, accompanied by an Army colonel, took Dr. James Goto, the chief evacuee doctor at Manzanar, and his wife to a restaurant in Lone Pine "where a too-obvious display was made of serving cocktails and the "de luxe' dinner." [14]

The deteriorating public relations also resulted from the fact that the Army and WCCA had contracted much indebtedness in the nearby communities, none of which had been paid by June 1. After the WRA takeover, the center finances were handled by Central Administrative Services in San Francisco. Payment of project obligations was so slow that most of the community did not desire to deal with the project, and some merchants went so far as to indicate that they did not desire the business of the appointed personnel. [15]

On June 26, less than a month after the WRA took over administration of Manzanar, George Savage, editor of the Inyo Independent and a member of the original local advisory committee for the camp, wrote a stinging editorial rebuke of Nash and WRA management policies. Prior to this time, his editorials had provided strong support for the Manzanar camp, but Nash's activities had turned that support to disgust and frustration, if not outright opposition. This editorial reflected the growing widespread opposition to Manzanar by the Owens Valley populace, and, according to Brown and Merritt, that disgust was "to be found with the employees at the project and was beginning to infiltrate in the evacuees." Among other things, Savage observed:

Milton Eisenhower, Director of the War Relocation Authority ... is reported to have resigned last week as Director. . . .

We wonder if Mr. Eisenhower hadn't come to realize that the WRA is a hot potato, just a little too warm to handle with bureaucratic tongs.

The WRA, with its social service approach to Japanese problems plus its very evident examples of maladministration, already had two strikes against it. ...

We believe wholeheartedly that the administration of the Japanese, in all camps, whether they be relocation areas or assembly centers, should be under direct charge of the United States Army, with an agency like the WCCA, which was directly answerable to the Army. . . .

In regard to the present administration at Manzanar, we cannot understand how Director Roy Nash can completely ignore the people of this county on the policies he is establishing there.

He is releasing Japanese to go on picnics and parties to points other than in the relocation area. A number of Japanese were taken last Sunday to Seven Pines and Kearsarge Valley. Another group was on George's Creek, fishing.

In view of the fact that federal jurisdiction has not yet been settled, insofar as Manzanar is concerned, and that Army responsibility is being ignored in permitting Japanese to leave the camp, Mr. Nash can hardly expect to have his program welcomed with open arms by the people of Inyo.

We would like to ask why Mr. Nash has not been more cooperative with the Ross Aeronautical School, which is seeking a small water supply for Manzanar airport use? Does Mr. Nash and the WRA think it more important to ignore the training of pilots for Army service in favor of the Japanese who have been evacuated here?.. . .

Mr. Nash promised some time ago to discuss local problems with the Board of Supervisors. To date he had not done so.

We would like also to ask why Mr. Nash hung up the telephone on the Inyo county deputy district attorney recently? A good administrator is at least courteous.

And why is it, Mr. Nash, that a truck laden with Japanese, can go almost a hundred miles round trip from Manzanar to near Darwin to secure a Joshua tree for use in adorning a rock garden being built at Manzanar. And here we are joining with the nation in a scrap rubber drive to secure rubber to keep the needed wheels of our nation moving. Maybe it's more worth while to get Joshua trees by driving many miles on valuable rubber than it is to conserve rubber.

But, this is only one sample of the kind of waste one sees every day in and around Manzanar.

Why is it that Manzanar has to be in such a state of turmoil? Queer, isn't it, that most of this has occurred since Mr. Nash and WRA arrived on the scene.

We are thoroughly disgusted with the whole deal. [16]

MANZANAR CAMP OPERATIONS DURING 1942

Despite the declining morale in the Manzanar camp and its worsening public relations with Owens Valley residents, the new WRA staff began to assemble at the center during early June 1942. Although construction of the camp was not complete, the many facets of its operation, elements of which had first begun under the WCCA in March, slowly developed throughout the remainder of 1942.

Reports Division

The Reports Division at Manzanar, which evolved out of the "Information Service," was the first administrative unit to be developed at any assembly or reception center during the evacuation program under the WCCA. [17] The first evacuees arrived at Manzanar on March 21 in two busses containing 84 people. In this group were two former newspapermen who had been, respectively, the assistant editor and the English section editor of a daily Los Angeles Japanese newspaper. The day following their arrival, the two men offered their services to the Project Director, recommending that they set up an information booth where all incoming evacuees could get instructions and information and where administrative notices could be posted. The plan was accepted by Project Manager Triggs and on March 23 Manzanar's Information Service was established.

Earlier on March 15, 1942, Robert Brown, executive secretary of the Inyo-Mono Associates, was appointed as Public Information Officer for Manzanar. His duties included public relations with the small communities in Inyo County as well as the dissemination of information within the camp. Thus, supervision of the Information Service became his responsibility.

Manzanar Free Press. As evacuees began pouring into Manzanar in late March and early April, the need arose for some means of disseminating information throughout the center in addition to the efforts of the Public Information Office. Brown recommended to his superiors in San Francisco, after obtaining the concurrence of the Project Director, that a daily mimeographed newspaper be established. The suggestion was forwarded to DeWitt who denied permission to print a newspaper. In spite of the denial, the need for dissemination of information became so great at Manzanar that the WRA's Chief of Public Relations in the San Francisco and Robert Brown "decided to launch a newspaper on their own authority and present the accomplished fact to the office of the General, hoping that the product would be so good that it would force that office to recognize the need and accept the answer to the need."

The name, Manzanar Free Press, was suggested by the Chief of Public Relations in San Francisco. According to Brown, it "was hoped that the name would give the people who were later to work on the paper a feeling of pride and that they would strive to uphold the best in newspaper tradition in writing news honestly, fearlessly, and with complete freedom of mind." [18]

The first issue of the Manzanar Free Press was printed on a mimeograph press on April 11, 1942, when the center had, according to the headline, 3,302 residents. This newspaper was the first of its kind to be printed in an assembly or relocation center. It was a two-sheet, four-page, two-column edition, put together by a hastily recruited staff of five evacuees by Brown whose work records showed some experience on newspapers.

A small article on page one of the newspaper was addressed to DeWitt, complimenting him on his understanding and humane operation of the mechanics of the evacuation. [19] According to John D. Stevens, an associate professor of journalism at the University of Michigan who researched assembly and relocation center newspapers, these were the "first and only kind words which ever appeared in an evacuee publication about the man most" evacuees "blamed for their removal." A week later DeWitt, perhaps influenced by the article in the Manzanar Free Press, gave official blessings to issuance of newspapers in all centers. [20]

According to Brown, during the first several months of the newspaper's publication, various individuals representing groups within Manzanar attempted "by every method from persuasion to threat" to gain control of the newspaper. Despite these attempts, Brown asserted that "at no time did any special interest or special group 'control'" the newspaper, although he believed that prior to December 6 "its pages and its editorials were aimed perhaps too exclusively at the Nisei." In its earliest days, "when it was accused of being totally Nisei, the FREE PRESS had served a greater cause, as many of its editorials were reprinted in daily papers from coast to coast enlightening thousands of readers to whom the evacuation was merely a wire-service dispatch from the West Coast."

The first issue of the Manzanar Free Press contained an editorial describing its editorial policies. The editorial noted:

We don't have a 'policy'. . . . Politics are out! We don't have to worry about what our advertisers think! We will have no circulation department worries .... This to a newspaper man or woman is plain Utopia. We should be able to devote all our creative effort to make this sheet one of the liveliest ever printed and one of the most democratic .... So far we don't even have an editor to worry us, so without this last bothersome detail, we should have a lot of fun. . . [21]

According to Brown, this editorial was "written purposely to allay fears that the paper was a 'voice of the management,' or the 'voice of the Nisei,' or the voice of anything." There was no editor, because management "was slowly feeling its way toward solving the complexities of leadership." Soon after the first issue, an "editorial board" was established consisting of the original four reporters — Joe Blarney, city editor; Sam Hohri, feature editor; Chiye Mori, news editor; and Tomomasa Yamasaki, editorial. [22] On May 19, six weeks after the first issue Yamasaki, was named the editor. [23]

After two weeks as editor, Yamasaki was elected a Block Leader. He left the newspaper, and the editorial board again functioned as a group.

On June 9 the Manzanar Free Press printed an editorial announcing a "new policy." The editorial stated:

We want to repeat again that the Free Press belongs to the people of Manzanar, that, instead of being merely the mouthpiece of the administration, it strives to express the opinions of the evacuees in the solution of immediate and foreseen problems.

If possible, we want to be the open forum for discussion of administration policies because these policies will directly affect every individual here. We know that the administration will welcome a healthy and active interest on the part of the residents as it is only with harmonious cooperation that our Shangri-La can be built. [24]

On July 22 the Manzanar Free Press was the first relocation center newspaper to change its format and become an independent journal, changing from a mimeographed sheet to a four-page printed newspaper in tabloid form. Chiye Mori became the new editor and served in that capacity until the December "incident." [25]

Since the newspaper staff members were able to relocate with relative ease, there was a continuous turnover in its staff. Because of this turnover it was necessary to carry on a program of in-service training. Young untrained people came to the newspaper office for training at the same time doing a day's work for the organization. During the first year the Brown gave considerable personal attention to training. Journalism classes were organized and held at night, using daily copy as text material. Shorthand classes taught by one of the secretaries on the staff were also offered. The chief mimeograph operator took one untrained person a month to train on mimeograph work. The head artist held weekly classes in illustrating and use of the stylus on stencils. Typists were coached in form and style by the senior typists.

From the beginning of the newspaper, many Issei evacuees at Manzanar complained that, because the newspaper was written exclusively in English, it was only for the Nisei and that it meant nothing to them since they could not read English. For a period it was felt that this might be a means of inducing those Issei who could not read English to study the language, but, according to Brown, "it was soon discovered that this was an idle dream."

Both camp management and the editorial staff of the newspaper understood the difficulties of issuing a Japanese edition of the Manzanar Free Press. Most of the Nisei on the newspaper could not read Japanese, and those who could cautioned against issuing such an edition because of attempts which might be made to write with "double meaning."

Nevertheless, camp management realized that only the younger people in the center were being reached by the newspaper. Efforts were undertaken to find some means for issuing a Japanese language supplement which would be a "strict translation of the English version, but which would get the news across to the older residents." In May and June 1942 two persons joined the appointed personnel who could read Japanese. In July the Catholic Church appointed a priest to aid the Catholic congregation at Manzanar who could also read Japanese. Using these staff members as a "board of censors," management felt it could begin issue of a Japanese language edition. An editorial board, composed of an Issei, Kibei, and Nisei, was chosen for this section of the newspaper. Copy had to pass all three for clarity, form, and content before it was submitted to the appointed personnel board and printed.

The WRA office in San Francisco was informed of the decision to publish the paper in Japanese. That office informed various security agencies and requested that management forward copies of all Japanese language editions to these agencies. The newspaper published 11 issues with Japanese sections in June 1942 before Washington ordered it to stop. The section resumed August 21, but like similar sections in other centers, it was supposed to carry only translations of material published in the English section. That policy changed on October 1 when it was announced that the four-page Japanese language supplement would publish original as well as translated material subject to WRA guidelines. [26]

The goal of the newspaper's original staff was to replace the mimeographed format with a printed sheet as soon as finances could be found to fund such an operation. When the Manzanar Cooperative Enterprises was established in June 1942, the newspaper staff approached the cooperative's board, asking that it underwrite the cost of six printed issues with the understanding that (1) as outside advertising came in, the cost would be reduced to the cooperative, and (2) that advertising space would continue to be available until the initial underwriting cost was absorbed. It was agreed that if advertising revenue did not cover the cost of the paper, the cooperative would absorb the difference. In return, the newspaper would make available to the cooperative enough space to balance the cost at regular advertising rates. This space could be used for an educational or news column with material exclusively aimed at developing interest in the cooperative movement at Manzanar. Outside advertising revenue was not sufficient to cover the entire cost for each issue, and the cooperative continued to underwrite or take enough advertising to keep the newspaper in printed form until near the closing of the center in 1945.

After this agreement with the cooperative, the masthead of the newspaper carried a statement that described its publishing status. The statement — "Official Publication of the Manzanar Relocation Center Administration, and Newspaper of Manzanar Community Enterprises." According to Brown, this differentiation between editorial control and ownership continued until the end of the publication — "not without its struggles, by any means — but the status was maintained."

The newspaper was supplied free of charge to all evacuees. Extra copies sold at five cents each, while initial mail subscriptions and subscriptions to appointed personnel were six dollars a year or 50 cents per month. Advertising rates initially were 35 cents an inch. At its height, circulation reached 3,700 copies, and mail subscriptions covered virtually every state in the nation. The financial support provided by the cooperative, which was in effect owned by the residents, made it possible to produce a newspaper at a cost of less than one cent per person per month. Advertisers included many local firms in Inyo County that sold merchandise to the cooperative and many national firms such as Sears, Roebuck and Company, the Wool Trading Company of New York, and the Golden State and Borden milk companies.

The Chalfant Press, owned by George Savage in nearby Lone Pine, printed the Manzanar Free Press from July 22, 1942, onward. Difficulties developed because the newspaper's evacuee editors could not leave the center to go to the print shop when the copy was ready for printing. Nor was it possible to run proofs to bring them back to the center to make up a dummy for retransmission back to the printer. The printer, in turn, was handicapped by a small staff.

These difficulties were worked out by careful editing of typewritten copy and by giving the linotype operator and printer a concentrated education in Japanese names and phrases. The linotype operator edited most of the copy as he cast the slugs, and the printer filled in where he missed. The cooperation of this firm "went far to make the paper the success that it was from a layout and production standpoint." [27]

Documentary Reports. Soon after the WRA assumed administrative control of Manzanar on June 1, 1942, Brown recommended that a documentary record be started that would be more of a summary of the life in the center than was being documented by the Manzanar Free Press. He believed that the reports should be written to provide background for events or currents in center life, and that they should emphasize the evolving life of evacuees in the camp, provide an interpretation of life in the center, and occasionally provide evacuee opinion sampling.

Joe Masaoka, an evacuee who as a Japanese American Citizens League leader had gained considerable recognition before the evacuation in newspaper circles in Southern California as a result of his cooperation with military and naval authorities, was chosen to prepare the documentary reports. As his assistant, he chose Togo Tanaka, the prewar English-language editor of the Los Angeles-based Rafu Shimpo newspaper. According to Brown, as "events turned out, the wisdom of choosing the latter could be questioned, but the choice of the former paid good dividends to the management of the Center and to the national program."

This team turned in its first report on June 9, 1942. Reports, written in a "news-magazine style," were submitted at a rate of two or three a week until December 7, 1942. Excerpts from the reports, or at times the complete reports, were sent to the WRA Regional Office in San Francisco to keep that office apprised of events at Manzanar. After the December 6 incident, the authors of the special documentation were relocated for their protection. Thereafter, a system of reporting from the blocks was instituted, which "probably gave a better overall picture of daily events, but which lacked the color of the earlier reports." [28]

Daily Block Reports. The aforementioned Information Office was destined to play a vital role in the early administration of the Manzanar camp. Under the general supervision of the WCCA's Welfare Section, the Information Office established four branches in the center, employing 57 people, and performing a variety of services. The office handled inquiries and complaints, translated letters for residents from Japanese to English and vice versa. For a period, it handled mail before establishing an independent mail system within the center. It wrote all bulletin material in both English and Japanese, and handled a "Volunteer Service Corps" which grew to include 450 persons who worked without pay helping incoming evacuees to get settled.

Shortly after administration of the center was taken over by the WRA, the first attempt at representation within the blocks was started. Block Leaders were appointed by the administration from candidates who were nominated by the block residents. The Block Leaders met and elected a chairman. Out of this came a "Town Hall" organization and a weekly meeting of Block Leaders with the Project Director.

Conflicts arose between the Block Leaders and the managers of the Information Service. The residents had become comfortable with taking their problems to the Information Office, and the staff had either answered questions and complaints or forwarded the questions to the camp administration for discussion with officials. Because the system worked smoothly, residents were slow to fake their troubles to the newly-elected or appointed Block Leaders.

On May 20, 1942, supervision of the Information Office was transferred from the Welfare Section to the Information Office. By June 1, when the WRA took over, it was apparent that the conflict between the Block Leaders and the Information Office workers had to be settled. A plan was developed to break up the Information Office as a unit and transfer its personnel to the Block Leader organization. In the new organization they would act as clerks for the Block Leaders, carrying on the type of work they had been doing, while the Block Leaders were left free to work with people in the blocks, attend meetings, and supervise the work of their assistants.

The two top men of the Information Office were offered positions, one as chief clerk in the "Town Hall" or main office of the Block Leaders, the other as assistant to the reports officer. It was determined that the clerk in the Block Leaders' office would make daily reports of happenings, conditions, complaints within each block. The reports would be forwarded to the chief clerk in the Town Hall, who would answer most questions, discuss questions of importance with the reports officer and his assistant, and prepare a daily summary of activity which the reports officer would circulate to staff members and forward to the Regional Office in San Francisco.

Approximately half of the staff of the old Information Service joined the new Block Leaders' organization which continued until the center closed in 1945. This organization served as a two-way channel of information — from the residents to Town Hall and the management and from the management, through Town Hall, back to the residents.

The daily reports of the Block Leaders are one of the principal sources of information for an understanding of the daily activities, concerns, and issues facing the evacuees at Manzanar. A digest of the block reports for October 1942, for instance, states that the "35 Block Managers turned in 424 daily reports" during the month — "an average of 12 reports for each block for 27 business days of the month." The digest indicated that (I) improvements to the barracks and a variety of recreational programs were underway, (2) some evacuees were requesting an explanation of the WRA's organizational structure and demanding to know how soon their private furniture would be delivered from private storage, (3) evacuees were interested in having photographic and watch repair shop services as well as weekly movie entertainment established in the camp, and (4) one of the principal problems facing the evacuees was what to do with their leisure time. [29]

Administrative Reports. When the Washington Office of the WRA developed standard monthly report forms in late 1942, the Reports Division handled this routine duty. Two evacuee staff members were detailed to work with division and section heads to prepare the forms for mailing to Washington. Material for the standardized reports was generally forwarded in rough draft form or telephoned to the Reports Office, and the forms were compiled and edited by the reports officer.

Mess Hall Operations

Under WCCA. On March 19, 1942, Joseph R. Winchester began work at Manzanar as Chief Project Steward, a job he would hold throughout the duration of Manzanar's operation under both the WCCA and the WRA. The next day food was unloaded from trucks and stacked on the ground under "military guard." Stoves and kitchen equipment were stacked beside partially-constructed Mess Hall 1 where they would remain for several days.

While talking with the "volunteer" evacuees on March 21, Winchester met "an alien Japanese who had managed a restaurant." Within two hours, about 30 evacuees "with restaurant experience or a willingness to do kitchen work temporarily placed a stove in the middle of the first mess hall, prepared food there, and served the first camp meal," composed of "canned goods, Army 'B-type rations.'"

Perishable food was not acquired for almost a week, except for bread which was delivered on March 21. To protect the bread from the ever-present Manzanar dust, Winchester placed it "in a panel truck." Mess hall 1 was completed on March 22, and Winchester instructed his embryonic crew, because 710 evacuees would arrive the following day via a motor caravan from Los Angeles.

Dishes were washed in small household-type dishpans in water heated on coal stoves, some of which were set up in the open. Water was trucked from "a well half a mile away." Not until "about April 4, when there were 3,286 people in residence and the sixth kitchen was open, were sinks, sewers, and water-main connections completed."

To find additional help for the expanding mess operations, Winchester, with the aid of an interpreter, met arriving evacuees and questioned them as to their work experience. Those selected for mess operations were allowed a day to unpack and settle before starting work. An evacuee typist was hired for clerical work, and an appointed storekeeper was employed to handle food supplies.

Around April 18, when ten mess halls were in operation, Winchester was sent to other assembly centers to aid in organization of their mess operations. A newly appointed staff employee, having been trained for mess management at another center, assumed charge for a short time at Manzanar. He, in turn, was replaced by another steward who came for a week's training before taking over the mess operations.

The first kitchens each fed an average of more than 600 people per day. To feed incoming evacuees, the messes remained open until after midnight during the early months of Manzanar's operation. Newcomers ordinarily arrived so late that their processing was not completed until "10 or 11 o'clock and sometimes later." The practice was to feed them before they were assigned to their quarters for the night, thus resulting in long hours for the mess workers. Two crews, totaling 60 men and women, were needed to staff each mess hall.

When new mess halls were opened, Winchester selected "a capable-appearing cook" with orders to organize a crew for the mess hall. Men were chosen for the new crew largely from operating facilities, while replacements were made from among the new evacuee arrivals.

By early April food storehouses were established beside the mess halls. Several months later, warehouses at the edge of the residential area were allocated to the Mess Operations Section.

Under the WCCA, Army B-type rations that were served to the evacuees included a "few perishables such as milk, potatoes, bread, and lettuce." There was no refrigeration at the center until around July 1; thus, two refrigerator cars were placed on the railway siding at Lone Pine to serve that purpose. A contract was made with the Lone Pine Ice Company to re-ice these cars every morning. Two trips a day were made by truck from Manzanar to the refrigerator cars for food supplies.

While Manzanar was administered by the WCCA, food was supplied by the Army Quartermaster Corps "in accordance with needs as the Army saw them." This at first produced some difficulties. The Quartermaster Corps, for instance, purchased large quantities of cottage cheese and buttermilk for the evacuees, but the residents, "unaccustomed to these foods, would not eat them." Instead, they wanted rice. According to Winchester, "It took several weeks to convince the Army that the rice requirement would range upward from a half-pound per day per person."

Under the WRA. When management of the center was transferred to the WRA on June 1, there was little change in mess operations except that the Chief Project Steward was replaced temporarily by a new man. A Mess Operations Section was established "to secure food supplies and to feed the evacuees." This section operated 36 mess halls, a kitchen in the hospital, and another in the Children's Village. The block kitchen next to the hospital was a special diet kitchen for the care of ambulant persons who, for reasons of disease or ill health, required special feeding, but did not need complete hospitalization. In addition, because the camp was isolated from ordinary community facilities, the section supervised "a cooperative dining-hall for appointed staff personnel who did not find it possible or desirable to eat in their living quarters." Food and labor at the appointed personnel dining hall were paid for by those who used the facilities. The Mess Operations Section also supplied the military post adjoining the camp with perishables and all supplies until 1944.

Under the WRA, food for the Manzanar mess halls continued to be requisitioned from the Army Quartermaster Corps, although for a time each requisition required approval from WRA officials in San Francisco. This practice, according to Winchester, resulted in difficulties, "because people away from the Center did not appreciate the eating habits of evacuees," frequently substituting "an un-ordered item for an ordered item." For instance, officials in San Francisco "considered it good business to accept 110 tons of cracked wheat which was obtainable in return for the payment of freight and handling charges." The evacuees did not care for cracked wheat, and the shipment arrived marked "unfit for human consumption." The result was that it was fed to poultry and livestock. Similarly, dried figs were substituted for other fruits "for so long that they were refused by tired appetites and a dangerously large over-supply accumulated on the Project." In August 1942, San Francisco approval of requisitions was no longer required.

Construction of the kitchens and mess halls was slow and equipment was often inadequate. When Winchester returned to his position as Chief Project Steward at Manzanar on July 1, only 23 mess halls were open. Although construction of the others was complete, a shortage of equipment delayed their opening. All of the mess halls were placed in operation, however, during the succeeding weeks. Winchester commented on some of the early problems facing operation of the mess halls:

From the first, and in spite of makeshift facilities, mess halls functioned smoothly. Supply was not always perfect but there was never a shortage of good wholesome food. Great concern was felt, however, because of inadequate facilities for sanitation, and this condition was watched closely and with considerable fear. Fortunately nothing developed except two very mild epidemics of diarrhea.

A problem in food arose out of conflict in food tastes between the desires of the first-generation Japanese and their American-born children. The older people were accustomed to, and desired, larger amounts of rice and Japanese food than were acceptable to the younger people. Limitations on the money granted for food, made it possible for the older people to have things more nearly their way, for Japanese food is economical.

Policies: Cost — The policy of the Mess Operations Section, governed by a WRA administrative instruction issued on August 24, 1942, was to "provide good wholesome, nutritious, palatable food at a daily cost of not more than 45 cents per day per resident, and to maintain high standards of sanitation and cleanliness." During 1942, consumption of "a large quantity of home-produced vegetables" enabled the section to more than meet that cost policy. The Mess Operations Section purchased these home-grown vegetables and melons from the Agriculture Section at Manzanar at approximately Los Angeles market prices.

Policies: Menus — Menus at Manzanar, as at all centers, were based on those prepared by the Subsistence Section of the Service of Supply Division of the Army. An attempt was made to satisfy both the Americanized tastes of the second-generation evacuees and the predominantly Asian appetites of their alien elders. Fancy grades of provisions, however, were expressly prohibited, and rationing restrictions were strictly enforced.

Meals at Manzanar averaged from 2,800 to 3,500 calories per person per day during 1942, With the exception of short periods when ration-point values were very low, meat consumption remained "approximately at the level allowed by rationing." Although "Japanese menus" contained "a greater amount of starch" than was "customary among Americans in general," every effort to provide palatable foods was made by the evacuee stewards who prepared menus which the Chief Project Steward approved." A considerable part of the menu consisted of "rice, sukiyaki, miso, tofu, chop suey, chow mein, shoyu sauce, and pickled vegetables of all kinds."

Special facilities were established for feeding of babies, nursing mothers, invalids, and hospital cases. Because of acute dairy shortages, fluid milk was served ordinarily only to evacuees, such as the aforementioned, who had a need for special dietary treatment.

Policies: Sanitation — The sanitary conditions in the kitchens never satisfied the Chief Project Steward. While some kitchens maintained high sanitation standards, others did not. To improve conditions, regular inspections were conducted by evacuee inspectors, When the position of sanitarian was filled by an appointed staff member, he assumed the inspection task. Signs, posters, and meetings with chiefs "all played their part in a campaign for greater cleanliness." As a result, a few unsatisfactory kitchens were closed down for several days to enforce better conditions.

Service — Food was served cafeteria style "on heavy restaurant-ware dishes." A gong announced meal times, after which lengthy lines formed. In good weather a long line formed outside and in poor weather inside. At times, problems arose as some persons attempted to "get ahead of their neighbors."

One kitchen in four was staffed with two to three nutrition aides who, on doctors' prescriptions, prepared formulas for babies, and special meals at 10 and 2 for children too young to eat the regular center diet. Supervised by an evacuee woman, this service was at first under the technical guidance of the hospital, but later it was placed under the direct management of the Chief Project Steward.